Introduction

Our aim was to determine predictors for the presence and degree of demineralization during orthodontic treatment. This study was a post-hoc analysis of recruits for a randomized controlled trial. Two hundred thirty patients were included in this study and assessed for demineralization at debond by using quantitative light-induced fluorescence to determine their eligibility for a randomized controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of various toothpastes at reducing demineralization during retention.

Methods

Data about patients’ demographics, treatments, oral hygiene, and pretreatment status of the first permanent molars were extracted from case notes. Data on the presence and severity of white spot lesions (WSLs) were obtained from the trial’s data base. Univariate analyses and multiple regression were undertaken to assess for associations between the factors and the presence and severity of WSLs.

Results

Sixty-five patients (28.3%) had no WSLs, and 165 (71.7%) had 1 to 12. The mean number of WSLs per patient with demineralization was 2.9 (95% CI, 2.5 and 3.3). Patients with WSLs were significantly ( P = 0.002) younger and more likely to have diseased first molars ( P = 0.04). Participants with inadequate pretreatment oral hygiene developed more WSLs ( P = 0.03). Boys ( P = 0.001) and participants with diseased first molars ( P = 0.06) had significantly greater demineralization.

Conclusions

Sex, pretreatment age, oral hygiene, and clinical status of the first molars can be used as predictors for the development and severity of WSLs during orthodontic treatment.

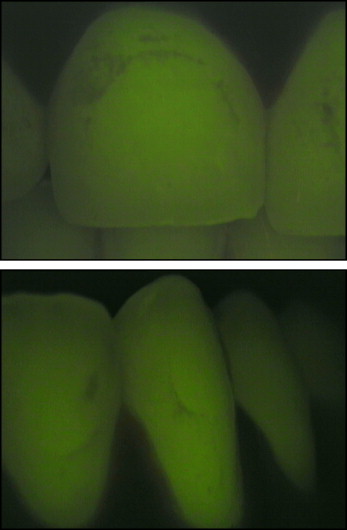

Demineralization of enamel surrounding orthodontic brackets is a significant clinical problem during and after orthodontic treatment. It is a major element of risk to patients when considering the risk-benefit balance of orthodontic treatment. Demineralization is an early stage of dental caries that occurs when plaque is allowed to remain on the tooth surface for a critical length of time. In orthodontic patients, demineralization is normally seen as white or brown spots on the enamel around the brackets and can lead to cavitation ( Fig 1 ). These spots usually occur on the labial or buccal surfaces of the teeth, which are not generally susceptible to demineralization in nonorthodontic patients. These iatrogenic white spot lesions (WSLs) can lead to poor esthetics and, in severe cases, the need for restorative treatment. Enamel demineralization is an undesirable but common complication of orthodontic fixed appliance therapy. Several studies have reported a significant increase in the prevalence and severity of demineralization in patients after orthodontic treatment. The incidence of WSLs reported in the literature varies from 2% to 97%.

Several methods have been used in clinical studies to detect and measure quantitatively demineralization. These are based on clinical or photographic examinations or other nonfluorescent or fluorescent optical methods including quantitative light-induced fluorescence (QLF). QLF is an optical, visible light-based system that can be used to detect and quantify early demineralization of enamel. It uses an arc lamp with a liquid light guide. The light passes through a blue filter in front of the lamp and has a peak intensity of 370 nm.The QLF technique has been found to be a sensitive clinical method suitable for longitudinal quantification of incipient carious lesions on smooth enamel surfaces. The aim of this study was to identify factors associated with the presence and the degree of demineralization during orthodontic treatment.

Material and methods

This study was a post-hoc analysis of patients recruited to a randomized controlled trial (RCT) at Liverpool University Dental Hospital in the United Kingdom. The sample size was determined by the number of patients who were recruited or screened for recruitment for an RCT that assessed the effect of various fluoride concentrations in toothpaste on remineralization of WSLs after orthodontic treatment.

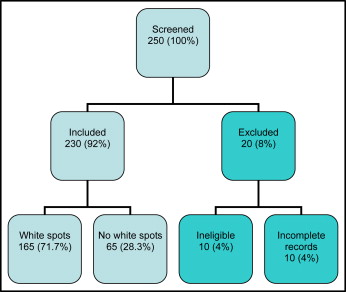

Two hundred fifty patients, who had completed their fixed orthodontic treatment and volunteered to participate in the RCT, were eligible for this study. All patients were recruited from the same dental teaching hospital. From the original 250 patients, 10 were subsequently excluded, since they were unsuitable for the QLF technique because of staining, fluorosis, enamel hypoplasia, or gingival overgrowth that made the QLF images inaccurate and therefore invalid. Ten patients were also excluded because their records could not be found. This left 230 patients who were included in this study ( Fig 2 ).

The RCT was assessing the effectiveness of toothpastes of different fluoride concentrations at remineralizing WSLs after orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances. The inclusion criteria were that the patients had completed treatment with maxillary and mandibular fixed appliances, had at least 1 WSL detected by QLF at debond, and were 13 years or older at debond. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy or concurrent medication, and those who were undergraduate dental students or involved in another clinical trial.

Data were extracted from the patients’ records and collected for the RCT. Forty-two patients were randomly selected by an author (J. E. H.), and their data were reextracted 4 weeks later by the first author (E. Al M.) to assess the reliability of the data extraction. Data were extracted from the patients’ records and entered on a data collection form. Data were later transferred to a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) for data analysis. The data included (1) demographic details, such as the patient’s hospital number, which was used as a reference number; (2) the date of birth, which was used to calculate the age of the patient at the start of treatment, and (3) the postal (zip) code, which was used to determine socioeconomic status. A home address located in one of the 20% of the most deprived areas in England was used to assess the impact of the patient’s socioeconomic status on the outcome.

Timing of treatment included the date when treatment started, identified as the date of bond-up of a fixed orthodontic appliance or the fitting of a functional or removable appliance, which was then followed by treatment with fixed appliances. The date that treatment ended was the date of debond. These dates were used to calculate the duration of treatment and the patient’s age at the start of treatment.

Types of treatment included fixed appliance therapy either alone, after treatment with a removable or functional appliance, or combined with an osteotomy to correct a skeletal discrepancy. The 2 main types of fixed orthodontic appliances used were a preadjusted edgewise appliance (0.022 × 0.028-in slot) and a Tip-Edge Plus appliance (0.022 × 0.028-in slot) (TP Orthodontics, LaPorte, Ind). Brackets and molar tubes were bonded with composite (Transbond, 3M Unitek, St Paul, Minn), and bands were cemented with glass ionomer cement (KetacCem, 3M ESPE, St Paul, Minn).

Operator characteristics included the grade of the operator who carried out the orthodontic treatment. The operators could either be a National Health Service consultant orthodontist, a senior specialist registrar in orthodontics—ie, a trainee who had completed specialist (graduate) training and was undergoing further training to become a National Health Service, hospital-based, consultant orthodontist—or a specialist registrar such as a graduate student in orthodontics. These were recorded because it was thought that the operator grade might have an effect on the outcome of the treatment, in particular the duration of treatment that was predicted to influence decalcification.

Dental health status included the patient’s oral hygiene and the status of the first permanent molars before treatment. Oral hygiene was recorded as adequate or inadequate (if it had been recorded in the patient’s case notes) or unrecorded (if nothing about the oral hygiene status had been written in the case notes) as assessed when the patients was first seen in the department. It was normal protocol for patients with inadequate oral hygiene when first seen to receive oral hygiene and dietary advice from a hygienist or the clinician. These patients were then taken on for treatment only when their oral hygiene was assessed as adequate to support the use of fixed appliances.

The clinical status of the first molars was thought to be a good indicator of the patient’s caries experience before treatment and, in turn, the risk of decalcification. The status was recorded as sound, restored, carious, or lost. Continuation sheets in the case notes, operators’ letters, pretreatment radiographs, and photographs were used to determine the clinical status of the first permanent molars before treatment.

Patient compliance included the number of attended appointments of the total number of appointments that were given to the patient. This was used to assess the patient’s compliance with the treatment. The total number of appointments included attended, missed, cancelled, and “broken brace” (emergency) appointments. The patient’s compliance with treatment was then calculated as the percentage of routine appointments attended out of the total number of appointments attended.

Additional data from the RCT data base were originally obtained by 2 operators using a QLF machine (Inspektor Research Systems, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to detect WSLs at the debond visit and then extracted from the data base for this study.

The WSLs had been assessed by using QLF as part of the recruitment process for the RCT. The basis of the QLF technique is that, under normal conditions, enamel auto-fluoresces, whereas demineralized enamel results in a reduction of this fluorescence with respect to surrounding sound enamel. This difference in the intensity of the fluorescence allows the degree of demineralization to be quantified and the lesion monitored longitudinally to assess its activity. The loss of fluorescence in the lesion is then calculated by reconstructing the fluorescence intensity of sound enamel from the adjacent areas over the lesion. Various QLF parameters can be obtained from this calculation, including ∆F (the mean percentage loss of fluorescence that is correlated to the amount of mineral loss) and ∆Q (the integrated value of ∆F over the lesion area per pixel and the area of the white spots).

The data included the following.

- 1.

Presence of WSLs. The QLF machine was used to image the labial surfaces of the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth to detect any WSLs. The images were captured immediately after debond and stored in a computer ( Fig 3 ).

Fig 3 QLF images: the dark areas are areas of demineralization. - 2.

Number of WSLs. WSLs on each labial surface were considered 1 WSL. Therefore, the number of WSLs a patient could have ranged from 0 to 12 and represented the number of teeth affected by WSLs.

- 3.

Teeth affected by demineralization. We investigated the demineralization on the maxillary and mandibular anterior teeth (maxillary canine to canine and mandibular canine to canine) because they were considered to be some teeth most at risk of demineralization and where the esthetic impact of demineralization was greatest.

- 4.

Degree of demineralization. The degree of demineralization, which is the difference in the loss of fluorescence (∆Q), was obtained for 85 patients from the data collected for the RCT. This was then used to see whether any factor, or a combination of factors, assessed in this study was associated with the degree of demineralization that was calculated as the mean ∆Q per patient.

In this study, we looked at patient factors (age, sex, socioeconomic status, compliance with treatment, and oral health before treatment, including oral hygiene and clinical status of the first permanent molars) and treatment factors (type, duration, and operator).

Statistical analysis

Univariate analyses were undertaken, including the chi-square test (to assess differences in categorical data), correlation coefficients, and weighted mean differences (weighted by sample size) with their standard deviations and 95% CI values to assess associations between the single factors and the presence and number of WSLs and the degree of demineralization. Multiple regression and multiple logistic regression analyses were used to test whether there were multiple associations. Multiple linear regression was used to look for associations between the number of WSLs, degree of demineralization, and all patient and treatment factors studied. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess the association between the presence or absence of WSLs and the same predictive factors.

Results

The reliability study showed that the data extraction for the 42 patients selected for a second phase of data extraction was highly reproducible compared with the first phase of data extraction for these patients. Only 3 errors occurred, and these were in the number of WSLs.

Two hundred thirty patients (65% female, 35% male) were included in this study. Of these patients, 65 (28.3%) had no WSLs, and 165 (71.7%) had between 1 and 12 WSLs each. The mean age of all patients when they started treatment was 16.2 years (SD, ±6.2; 95% CI, 15.4 and 17.0). Of the patients with WSLs, the mean number of WSLs per patient was 2.9 (SD, ±2.8; 95% CI, 2.5 and 3.3). The patients’ postal (zip) codes were used to determine the index of multiple deprivation (IMD) and hence the patients’ socioeconomic status. Of the included patients, 117 (50.9%) were in the lowest quintile (ie, the lowest 20% of the IMD rating), suggesting that a high proportion of patients in the study were from some of the most deprived areas in the United Kingdom. Of the remaining half of patients, 49 (21.3%) were in the second quintile, 36 (15.7%) in the third, 15 (6.5%) in the fourth, and 9 (3.9%) in the fifth (least deprived) quintile.

The majority (77%) of patients were treated by specialist registrars (graduate students), 13% by senior specialist registrars, 9% by consultant orthodontists, and 1% by other grades of operators. One hundred forty-seven patients (64%) were treated with maxillary and mandibular fixed orthodontic appliances alone, 21 (9%) with functional appliances followed by fixed appliances, 36 (16%) with a combination of surgery and fixed orthodontic appliances, and 26 (11%) with maxillary removable appliance followed by fixed orthodontic appliances. The mean treatment length was 28.2 months (SD, ±9.8; 95% CI, 26.9 and 29.5).

The mean number of appointments attended was 19.6 (SD, ±5.8; 95% CI, 18.8 and 20.4), and the mean total number of missed, cancelled, and broken brace (emergency) appointments was 3.7 (SD, ±3.3; 95% CI, 3.3 and 4.1). Pretreatment oral hygiene was assessed as adequate in 106 (46.1%) of the patients, inadequate in 54 (23.5%), and not recorded for 70 (30.4%). All maxillary and mandibular first permanent molars were sound at the start of treatment in 110 patients (48%), but 120 patients (52%) had at least 1 diseased first permanent molar when they started treatment.

Of the 165 patients with WSLs, 59 (35.8%) were male and 106 (64.2%) were female, whereas in those without WSLs, 21 (32.3%) were male and 44 (67.3%) were female. This suggests that there was no statistically significant difference in the incidence of WSLs between the sexes (odds ratio [OR], 1.17; 95% CI, −0.63 and 2.15; P = 0.62). The mean age of patients with WSLs was 15.2 years (SD, ±4.4; 95% CI, 14.5 and 15.9) when they started treatment; the age of those with no WSLs was 18.8 years (SD, ±8.8; 95% CI, 16.6 and 21.0). This indicates that patients with WSLs were statistically significantly younger at the start of treatment than those without WSLs (weighted mean difference [WMD], 3.6; 95% CI, 1.33 and 5.87; P = 0.002).

Of the most deprived patients—ie, the lowest 20% on IMD score—32 (27.4%) had no WSLs; similarly, 32 (29.4%) of the patients who were the least deprived had no WSLs. These differences were not statistically significantly different (OR, 1.10; 95% CI, −0.62 and 1.97; P = 0.64), suggesting that a patient’s level of deprivation did not influence whether he or she developed WSLs ( Table I ).

| Least deprived | Most deprived | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| No WSLs | 32 | 29.4 | 32 | 27.4 | 65 | 28.3 |

| WSLs | 77 | 70.6 | 85 | 72.6 | 165 | 71.7 |

| Total | 109 | 100 | 117 | 100 | 230 | 100.0 |

When considering the patients treated by different grades of operator, there were no statistically significant differences between the number of patients who did and did not develop WSLs (chi-square, 4.55; degrees of freedom, 2; P = 0.103). The numbers and percentages of patients developing WSLs after treatment with each appliance combination are shown in Table II . These data suggest that using an appliance in addition to fixed appliances did not increase the risk of demineralization (chi-square, 2.69; degrees of freedom, 3; P = 0.44).

| Treatment type | No WSLs | WSLs | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | |

| Fixed alone | 38 | 25.9 | 109 | 74.1 | 147 |

| Functional and fixed | 5 | 23.8 | 16 | 76.2 | 21 |

| Osteotomy and fixed | 11 | 30.6 | 25 | 69.4 | 36 |

| Upper removable appliance and fixed | 11 | 42.3 | 15 | 57.7 | 26 |

| Total | 65 | 28.3 | 165 | 71.7 | 230 |

For patients with WSLs, the mean length of treatment was 28.3 months (SD, ±10.4; 95% CI, 26.7 and 29.9), whereas, for those with no WSLs, the treatment duration mean was 27.9 months (SD, ±7.8; 95% CI, 25.4 and 29.6). This difference was not statistically significant (WMD, 0.40; 95% CI, −2.08 and 2.88; P = 0.75).

For patients with WSLs, the mean level of compliance was 15.3% (SD, ±10.6%; (95% CI, 13.7% and 16.9%), whereas, for patients with no WSLs, the mean was 13.7% (SD, ±10.0%; 95% CI, 11.2% and 16.2%). This difference was not statistically significant (WMD, −1.62; 95% CI, −4.55 and 1.31; P = 0.28). Of the patients with adequate oral hygiene before treatment, 74 (69.8%) developed WSLs by the end of treatment, whereas 41 (75.9%) patients whose oral hygiene was assessed as inadequate developed WSLs during treatment. However, these differences were not significant (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, −0.64 and 2.88; P = 0.54). Of the patients who had at least 1 diseased first permanent molar (n = 120), 90 (75.0%) developed at least 1 WSL, and 75 (68.2%) with 4 sound first permanent molars developed WSLs. This difference was not statistically significant (OR, 0.71; 95% CI, −0.40 and 1.27). However, multiple logistic regression showed a significant correlation between WSLs and age at the start of treatment (OR, 0.90; Wald statistic, 12.99; P <0.001; 95% CI, 0.85 and 0.95) and pretreatment status of the first permanent molars (OR, 1.95; Wald statistic, 4.18; P = 0.041; 95% CI, 1.03 and 3.68).

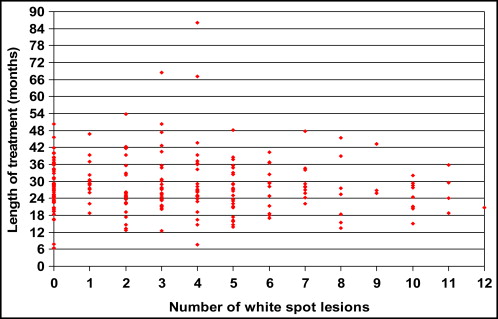

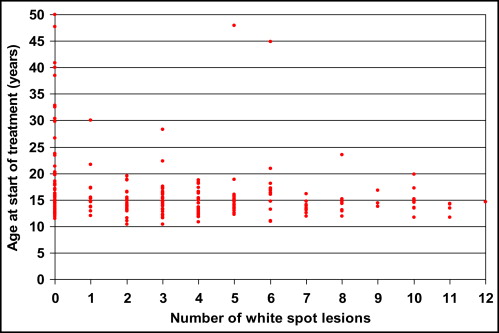

The mean numbers of WSLs were 4.4 (SD, ±2.7; 95% CI, 3.7 and 5.1) in the male patients and 3.9 (SD, ±2.2; 95% CI, 3.5 and 4.3) in the female patients. This difference was not statistically significant (WMD, 0.5; 95% CI, −1.31 and 0.31; P = 0.23). There was no statistically significant correlation between the age of patients at the start of treatment (r 2 , −0.186) or the IMD score (r 2 , 0.007) and the number of WSLs that they developed ( Fig 4 ). The mean numbers of WSLs were 3.4 (SD, ±3.0; 95% CI, 2.8 and 4.0) in patients living in the most deprived areas (lowest quintile) and 3.2 (SD, ±3.1; 95% CI, 2.6 and 3.8) in those living in less deprived areas. This difference was not statistically significant (WMD, −0.20; 95% CI, −1.00 and 0.60; P = 0.62).

The mean numbers of WSLs were 2.1 (SD, ±2.1; 95% CI, 1.1 and 3.1) in patients treated by consultants, 2.7 (SD, ±3.0; 95% CI, 1.5 and 3.9) in patients treated by senior specialist registrars, and 3.4 (SD, ±3.1; 95% CI, 2.9 and 3.9) in patients treated by specialist registrars. These differences were not statistically significant ( P = 0.122). The mean numbers of WSLs were 3.4 (SD, ±3.0; 95% CI, 2.9 and 3.9) in patients who wore fixed appliances alone and 3.1 (SD, ±3.1; 95% CI, 2.4 and 3.8) in patients who wore a combination of fixed appliances with another type of appliance. These differences were not statistically significant (WMD, 0.30; 95% CI, −0.52 and 1.12; P = 0.122). There was no statistically significant correlation between the length of treatment (r 2 , −0.045) or patient compliance (r 2 , 0.11) and the number of WSLs that patients developed ( Fig 5 ).