Facial asymmetry of varying degrees is present in all individuals. Some people have almost imperceptible asymmetry, whereas others have gross, severe deformities. The significance of the asymmetry is often in the eye of the beholder. A facial asymmetry that may be significant to one person may seem inconsequential to someone else. Significant and sometimes severe facial asymmetries are common in the population. In diagnosing and treating facial asymmetry, health care providers should be aware of the patient’s concerns and be able to diagnose as well as determine the required treatment for predictable and stable correction. Also, realistic treatment outcome expectations must be realized by the patient and clinicians. Of importance, a comprehensive examination should be performed and a specific diagnosis established as to the cause of the facial asymmetry. Failure to recognize and remove or correct the causative factor could result in a compromised or poor result with recurrence of the asymmetry and associated malocclusion. The more severe the deformity is, the greater the difficulty of treatment to achieve facial symmetry. The less experienced and skilled the surgeon is, the greater the compromise in surgical outcomes.

Facial asymmetry can occur in all three planes of space—vertical, transverse, and anteroposterior (AP)—and usually occurs in combinations of these. Facial asymmetry can involve one or more of the following four anatomic areas; dentoalveolar area, skeletal anatomy, soft tissues, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Dental alveolar asymmetry can involve the alveolar bone, teeth, and gingiva. Skeletal asymmetry can involve the cranial bones, orbits, zygomas, nasal bones, maxilla, and mandible. Soft-tissue involvement can include the skin, subcutaneous tissues, nerves, muscles, vascular structures, glands, nasal soft tissues, and so on. TMJ involvement may include the condylar head and neck, fossa, articular disk, bilaminar tissues, ligaments, muscles, tendons, and other associated structures.

Possible causative factors for facial asymmetry include genetics, birth molding, congenital and developmental deformities, abnormal growth, tumors or other pathology of facial structures and jaws, TMJ pathology, TMJ and jaw positional changes, trauma, neurologic or neuromuscular disorders or pathology, and iatrogenic injury. A comprehensive diagnosis, including identification of the causative factors, as well as an inclusive treatment plan can be achieved through a thorough and complete workup including (1) clinical evaluation; (2) dental model analysis; (3) imaging that may include Panorex, lateral cephalogram, PA cephalogram or Waters’ view, i-CAT scans, tomograms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, bone scans, three-dimensional (3D) imaging, 3D modeling, and so on; (4) laboratory tests; and (5) consultation with other health care providers necessary in diagnosis and patient management.

Hundreds of conditions can create facial asymmetry, as identified by Gorlin, Cohen, and Hemekam. This chapter is directed at the diagnosis and treatment of the more common facial asymmetry deformities. Conditions such as cranial deformities (e.g., plagiocephaly, cranial synostosis, orbital dystopia), torticollis, rare syndromes and conditions, and neuromuscular disorders (e.g., Bell’s palsy, Mobius syndrome, tumors) are not discussed significantly because of space limitations. Specific factors that will aid in diagnosis and treatment planning for the more common facial asymmetries are presented.

PATIENT EVALUATION

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Facial asymmetry is usually the least at the cranial base level and increases at lower levels of the face, with the mandible and chin commonly exhibiting the greatest asymmetry. Exceptions to this would include craniofacial deformities such as plagiocephaly, unilateral craniosynostosis, orbital dystopia, tumors involving the cranium and midface, and so on. In most facial asymmetry cases, cranial base structures can be used as the base reference for determining the type and extent of the asymmetry affecting the midface and jaw structures. The presence of orbital dystopia, unequal pupillary heights, and/or unequal ear heights will make the assessment more challenging. Detailed methodology of my comprehensive patient analysis and treatment planning has previously been published and will not be reiterated here. However, some basic evaluation factors helpful to assess facial asymmetry are presented.

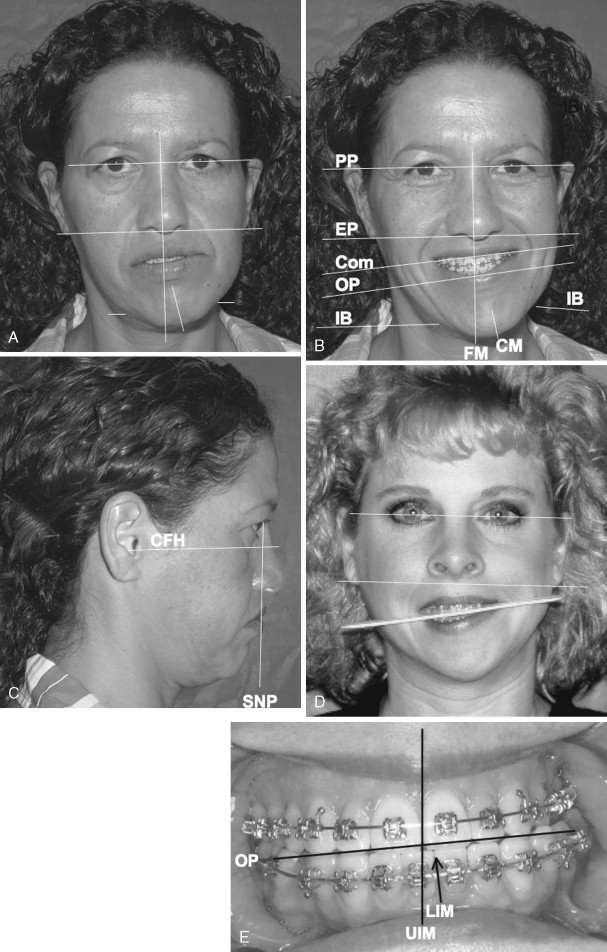

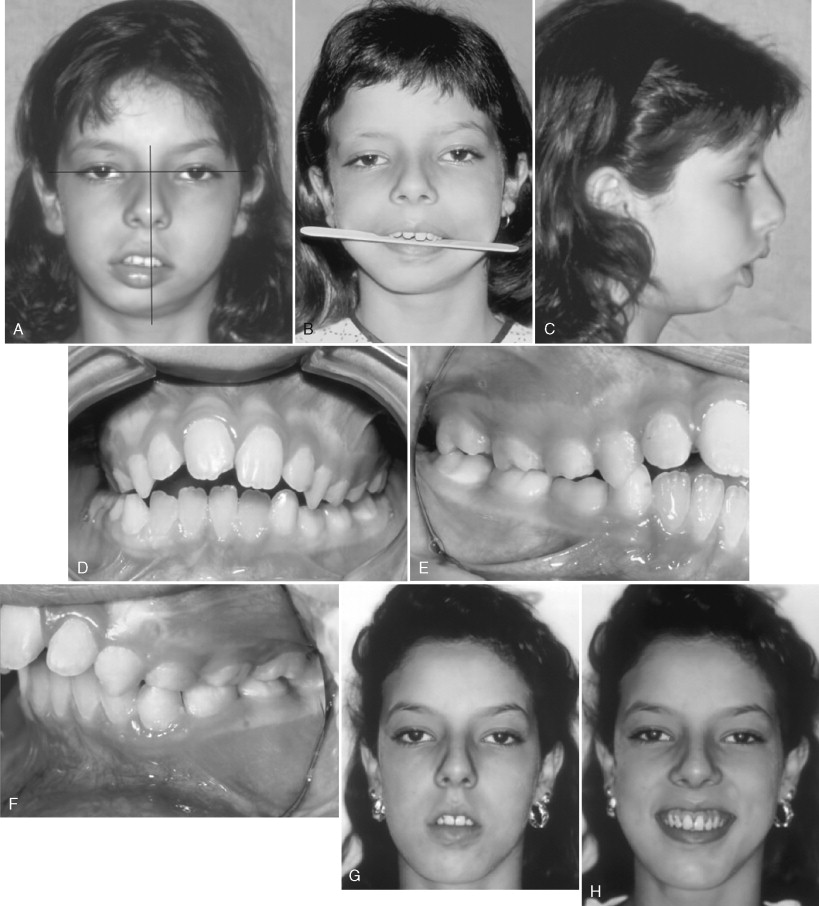

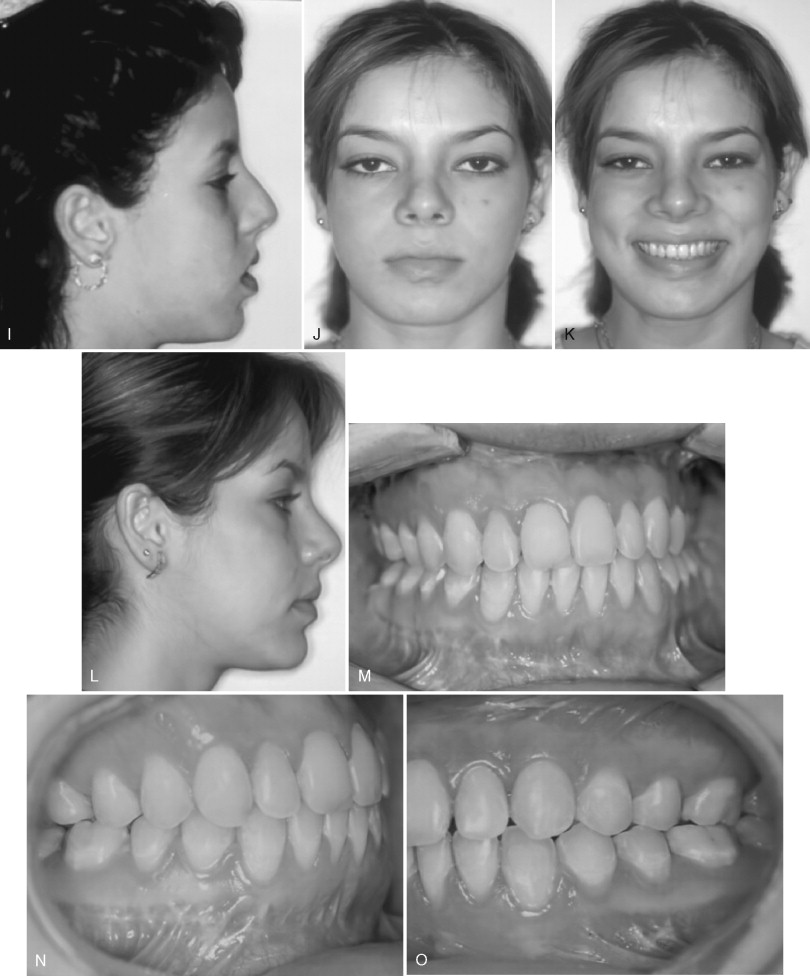

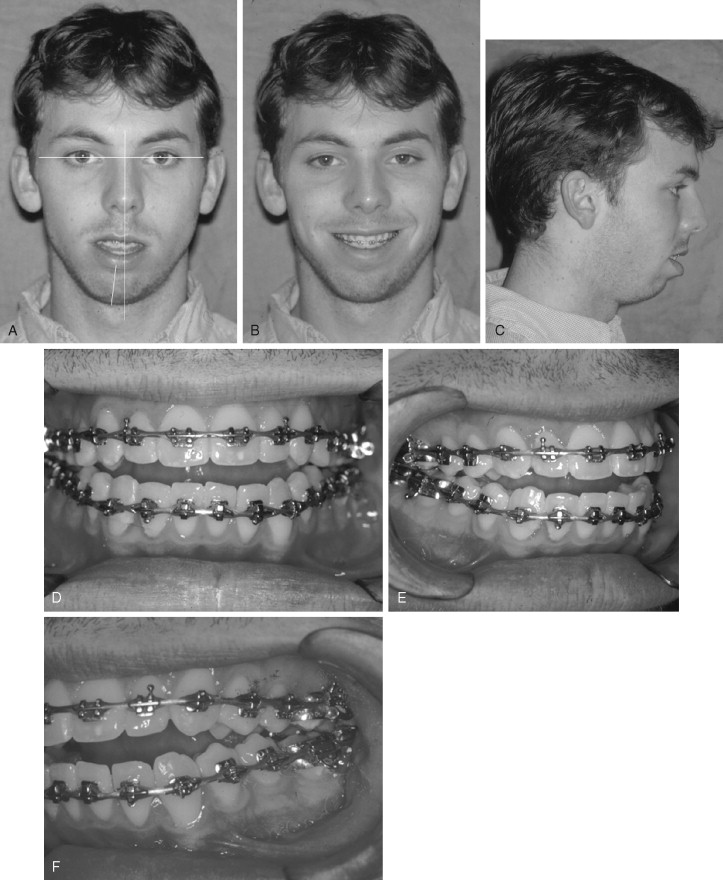

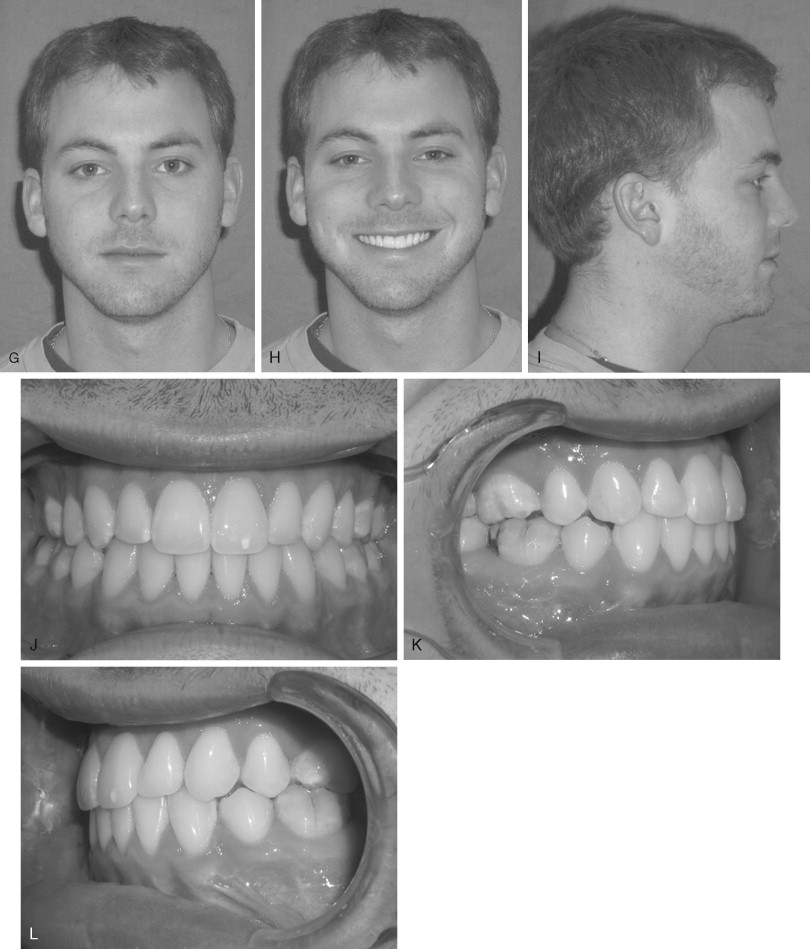

Frontal View

The frontal view evaluation can be performed by direct clinical examination and/or properly oriented photographs to determine the amount of vertical and transverse asymmetry ( Figure 13-1, A and B ). Head orientation is very important, as some patients will hold the head in an abnormal position to mask asymmetry. The pupillary plane and the plane through the bottom of the earlobes or tragus of the ears (ear plane) oriented parallel to the floor can be used for transverse head orientation. If the eyes and ears are vertically asymmetric, then corrective orientation of the head to the best transverse position of these planes may be helpful. Creating a vertical line directly between the medial palpebral fissures (usually the midline of nasion) perpendicular to the pupillary and ear planes extending downward below the inferior aspect of the mandible can be used to determine the degree of left-to-right facial asymmetry including such structures as the midlines of the maxillary and mandibular incisors as well as the chin and nasal structures (see Figure 13-1, A and B ). Transverse facial width discrepancies can be determined by measuring from the vertical facial midline reference to the transverse position of the orbits, globes, pupils, malar eminences, nose, cheeks, mouth and commissures, mandibular rami, angles, and bodies, as well as the chin morphology. The asymmetry should be assessed to determine if the problem is dentoalveolar, skeletal, and/or soft tissue based.

Vertical asymmetry can be assessed by using the pupillary plane as a reference to perform vertical measurements. Measurements can be done to determine vertical differences from the left to the right sides of the mandibular angles, bodies, chin, nose, and commissures. The vertical upper lip length and tooth to upper lip relation must also be evaluated. Placing a tongue blade transversely across the occlusion between the maxillary and mandibular cuspid or first bicuspid area can be used to determine the transverse cant of the occlusal plane relative to the pupillary plane (see Figure 13-1, D ). Opening the jaws slightly and then orienting the tongue blade so it is parallel to the pupillary plane will allow vertical measurement from the tongue blade to the cuspids to determine the amount of vertical discrepancy from the left to right sides. Also, evaluate the asymmetry of the smile and transverse level of the commissures (see Figure 13-1, B ).

An asymmetric mandible can usually be shifted toward the facial midline (except in TMJ conditions in which the condyle will not translate, such as fibrous or bony ankylosis) to get an improved perspective in the transverse dimension on the effect of surgical correction. The mandible rotates around one condyle, and the other must translate forward until the chin is relatively symmetric with the facial midline. The facial structures are then evaluated for asymmetry in this position to arrive at some indication of the effects of at least partially correcting the transverse mandibular asymmetry. Vertical and AP asymmetries will not be significantly affected by this maneuver.

Profile View

Patients with facial deformities often hold their heads abnormally for functional and/or esthetic reasons. In patients with deficient mandibles, the head is often tipped upward to improve chin projection and also to open the oropharyngeal airway. Therefore it is helpful to posture the head so that the clinical Frankfort horizontal plane (a line from the tragus of the ear through the palpable bony infraorbital rim) is parallel to the floor. Evaluating the left and right sides from the profile view will allow assessment of asymmetries in the forward projection of the forehead, globes, orbital rims, cheeks, and malar areas, as well as the maxilla, mandible, and chin. The profile view is generally more helpful in determining the AP and vertical position of the maxilla, mandible, and chin than asymmetry evaluation (see Figure 13-1, C ). Patients with Class III mandibular prognathic jaw relationship (see Figures 13-7, A and 13-8, A ) may have an overgrowth problem, whereas patients with a Class II skeletal relationship (see Figures 13-18, C ; 13-20, C ; 13-22, C ; 13-24, C ) will likely have a retruded mandible that could be related to a developmental deformity, condylar hypoplasia, or resorptive TMJ pathology.

Axial View

Standing behind the patient and looking downward at the facial structures or tilting the patient’s head backward and viewing from below (see Figure 13-13, B ) may help identify and quantify the amount of AP and transverse asymmetries of the facial structures mentioned earlier.

DENTOALVEOLAR AND OCCLUSAL ASSESSMENT

Evaluate the occlusion in a TMJ centric relation, not centric occlusion, if there is a difference between the two positions. Evaluate the dental arches for overdevelopment or underdevelopment; anodontia; deformed, decayed, impacted, missing, or ankylosed teeth; dental midline shift; dental crowding or spacing; AP, transverse, and vertical dental arch asymmetry; congenital deformity (e.g., unilateral cleft lip palate); growth aberration; habitual pattern; tumor or other pathology; radiation effects; trauma; iatrogenically induced deformity; crown shape and tooth size and position; and maxillary and mandibular arch yaw (see Figure 13-1, E ). Incorporate these findings into the diagnosis and treatment plan.

IMAGING

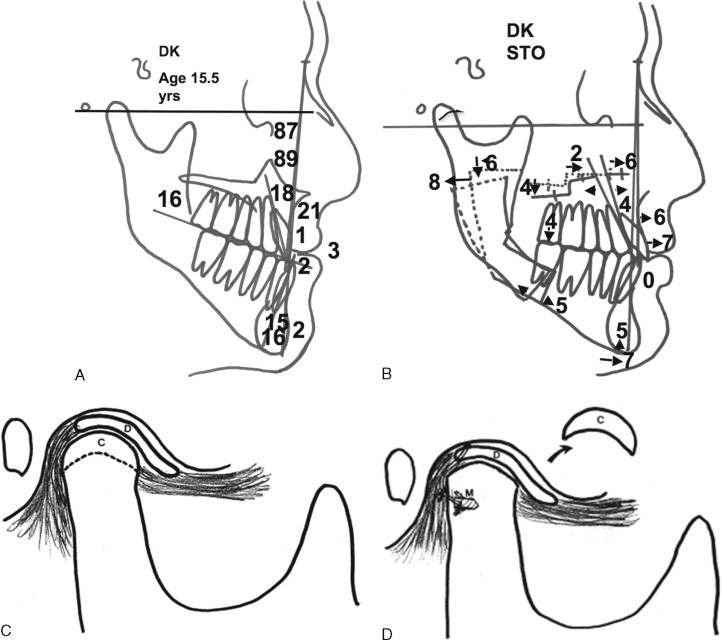

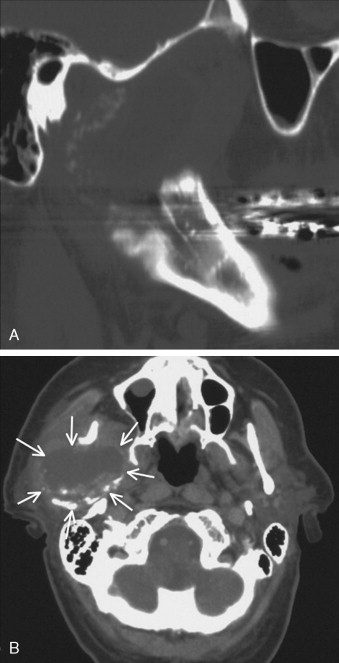

The lateral cephalometric radiograph is one of the most important tools in the diagnosis of jaw deformities. It is used to analyze skeletal, dentoalveolar, and soft-tissue relationships in the AP and vertical dimensions. For proper positioning the patient’s head should be postured so that the jaws are in TMJ centric relation with the teeth lightly touching and the lips relaxed. The head should be oriented so that the clinical Frankfort horizontal plane (a line through the tragus of the ear and the bony infraorbital rim) is parallel to the floor. Left-to-right side vertical discrepancies can usually be quantified on the lateral cephalogram by measuring between the double images of the occlusal plane and inferior borders of the mandible (see Figures 13-15, A and 13-25, C ). A posteroanterior (PA) cephalogram or Waters’ view can be helpful in determining facial asymmetry. Tracing and superimposing cephalometric tomograms that include the TMJ as well as the mandibular body and teeth, will allow quantification of the asymmetry, which may involve the condyles, rami, and bodies of the mandible. Serial tracings of lateral, PA, and tomo graphic cephalograms over time (usually a minimum of 1 year) may be helpful in determining if the asymmetry is static and stable or if it is progressive. In more severe asymmetry cases, 3D imaging and/or modeling can be beneficial for diagnosis and treatment planning. Bone scans may be helpful in some asymmetry conditions to determine if an active process is present, usually involving TMJ pathologies or tumors.

DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT FACTORS TO CONSIDER

Accurate diagnosis of the cause of the facial asymmetry is important for treatment planning. If the causative factor is not identified and addressed, then stability, function, and pain factors may be unpredictable, with asymmetry redeveloping.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT AND FACIAL ASYMMETRY

TMJ disorders and pathology are common causative factors or results of facial asymmetries, particularly affecting the mandible, and certain pathologies can produce a progressive worsening of the asymmetry and malocclusion. TMJ-associated changes usually occur at a relatively slow rate, from minimal change to 4 to 5 mm or more per year depending on the nature of the pathology. Other TMJ conditions may only cause pain and/or dysfunction without worsening facial asymmetry but may still need to be addressed for optimal treatment outcomes. Condylar underdevelopment or condylar resorption can cause the mandible and face to be smaller on one side and shift toward the involved side. On the other hand, a unilateral condyle, mandible, and associated structures can over develop (enlarge), causing facial asymmetry. In such patients the relatively normal side may also develop TMJ pathology (e.g., articular disk dislocation, arthritis) from the increased loading of that joint created by the overdevelopment of the opposite side. Therefore, performing orthognathic surgery only and ignoring the TMJs during treatment or failing to render proper TMJ management could result in redevelopment of the asymmetry and malocclusion, worsening TMJ-associated symptoms including jaw dysfunction and pain.

The TMJs should always be evaluated in a patient with facial asymmetry to determine if they are the causative factor, are associated with a problem that has developed because of facial asymmetry, are associated with a coexisting pretreatment condition, or are normal and healthy joints. Approximately 25% of patients with TMJ pathology or disorders will be asymptomatic. These are the patients whose condition can be more troublesome because the TMJ pathology may not be recognized, and therefore not treated, resulting in a poor outcome with potential redevelopment of asymmetry by condylar and mandibular overdevelopment or condylar resorption as well as initiation of pain, headaches, and other TMJ symptoms. Other patients will have overt TMJ signs and symptoms that could include one or more of the following: progressive facial and occlusal changes; history (previous or current) of TMJ click, pop, or crepitus; decreased jaw function; myofascial pain; TMJ pain; headaches; neck, shoulder, or back pain; open bite (anterior, lateral, posterior); earaches; tinnitus; vertigo; or development of speech and airway problems. Therefore treating facial asymmetries will often require surgical management of the TMJ pathology in order to have a highly predictable and stable functional and esthetic outcome as well as a pain-free treatment result. Nonsurgical TMJ treatment (e.g., splints, physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, orthodontics, medications) may help the TMJ symptoms but will not stabilize and eliminate TMJ pathology (e.g., disk dislocation, arthritis, condylar resorption or overdevelopment) to withstand the increased TMJ loading that usually accompanies the orthognathic surgery procedures necessary to achieve optimal functional and esthetic outcomes.

NUMBER AND TYPE OF PREVIOUS SURGERIES

The number of previous surgeries, particularly to the TMJ, may dictate the TMJ surgical procedure options. A patient with two or more previous TMJ surgeries will have a high failure rate if autogenous tissues are used for the TMJ reconstruction. A TMJ total joint prosthesis, such as the TMJ Concepts system (TMJ Concepts, Inc., Ventura, California) will have a much higher rate of success ( Figure 13-2 ). Patients with TMJ involvement of connective tissue and autoimmune diseases likewise may benefit from total joint prosthesis reconstruction because the disease processes will likely attack any autogenous tissues placed into the joint area but will not affect the total joint prostheses. Other end-stage TMJ conditions such as severe reactive arthritis or osteoarthritis, ankylosis, severe damage from trauma, failed TMJ alloplastic implants, and so on, particularly in adolescent or older age groups, will get the most predictable results with total joint prostheses and fat grafts packed around the articulating components of the prostheses.

The selection of the TMJ total joint prosthesis system is an important factor in treatment outcomes. Prostheses must have biocompatible and functionally compatible materials with a low wear coefficient, a posterior stop on the fossa, and components firmly fixed to the fossa and ramus with osseointegration and ideally would be custom-fitted devices. The downside to total joint prostheses is that it is unknown how long the systems will last. I have placed more than 550 TMJ Concepts total joint prostheses, with the longest follow-ups being at 19 years. No devices have been replaced because they wore out.

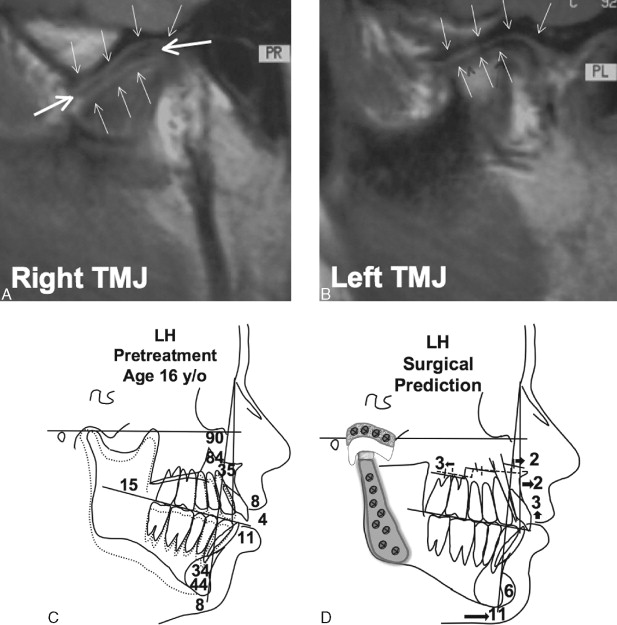

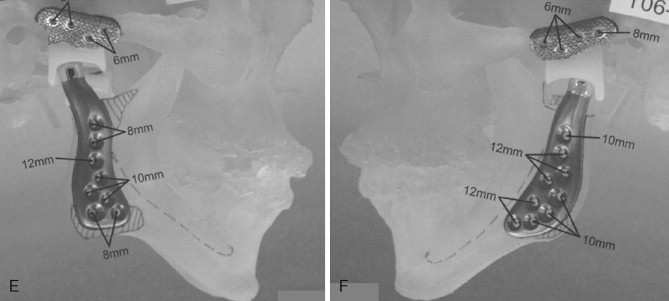

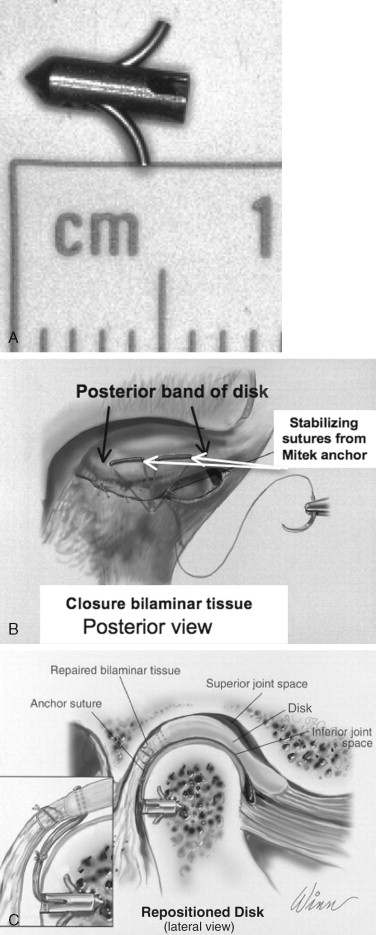

Patients with current or previous history of TMJ clicking or popping, TMJ pain, headaches, myofascial pain, ear symptoms, and so on related to TMJ articular disk dislocation who have undergone no or one previous TMJ surgery may benefit by articular disk repositioning and ligament repair with Mitek anchors (DePuy Mitek, Raynham, MA) to achieve a stable treatment outcome ( Figure 13-3 ).

An orthognathic surgery patient who initially has a good treatment result but subsequently develops facial asymmetry probably had a presurgical, unrecognized, and untreated TMJ pathologic condition. TMJ surgical intervention may be necessary to correct the pathology, in addition to repeat orthog nathic surgery, in order to achieve a high-quality stable result and pain-free outcome. A patient who may have vascular compromise to the maxilla or mandible from too many previous surgeries, smoking, or radiation therapy may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy presurgery to improve the vascularity and success rate.

PROGRESSION OF FACIAL AND OCCLUSAL CHANGES

It is important from a diagnostic and treatment planning standpoint to determine whether the facial asymmetry and occlusion are stable and static and whether the asymmetry and malocclusion are the result of a sudden change (immediate occurrence or within a few weeks) or if progressive changes are ongoing (slower continuous development that may take a few months to several years to identify). For predictable treatment outcomes, the TMJs must be stable, healthy, and free of pathology, or the asymmetry and malocclusion may redevelop and pain may occur after surgery.

Stable and static dynamics means there have been no active changes or progression whatsoever in facial asymmetry and occlusion for a minimum of 1 year. A stable static facial structure and occlusion without evidence of tumor or TMJ disorder or pathology and symptoms may indicate that the TMJ is not involved or at least not active in the current status of the facial asymmetry. However, in facial asymmetry the TMJs must still be thoroughly evaluated, as the TMJ pathology may merely be in a state of remission and could be reinitiated by TMJ stress and loading that will occur as the facial asymmetry is surgically corrected. If the facial asymmetry is stable and unchanging and there is no evidence of TMJ pathology or symptoms, then the asymmetry can be corrected with orthognathic surgery only, without TMJ surgery.

Sudden change indicates that abrupt development of facial and/or occlusal asymmetry has occurred, usually as a result of trauma, infection, condylar dislocation, neurologic or neuromuscular disorder, abnormal jaw posturing, poor orthognathic surgery outcome, and so on. The cause and associated deformities must be identified and appropriately corrected.

Progressive change indicates active pathology causing continued change usually as a result of TMJ disorders or pathology, tumor, growth variance, or tissue hypertrophy or atrophy. Progressive change generally indicates an active disease process or growth abnormality that may require additional procedures besides the orthognathic surgery to achieve stable predictable results. If the asymmetry is related to TMJ pathology, then TMJ surgery may be indicated in order to establish a stable, predictable, and pain-free outcome. Commonly observed progressive asymmetric changes include the following:

- •

Facial asymmetry that develops or significantly worsens from the early teen years or later in life is likely related to TMJ pathology or tumor.

- •

Progressively worsening unilateral Class III occlusal relationship with a contralateral cross-bite and shift of the mandible and chin to the opposite side may indicate a unilateral condylar hyperplasia (CH).

- •

Progressively worsening unilateral vertical lengthening of the face and jaws with lateral open bite on the involved side, usually with a Class I occlusion but with a significant transverse cant to the occlusion and face, usually indicates a unilateral mandibular condylar osteochondroma or osteoma.

- •

Development and progressive worsening of an anterior open bite and Class II occlusion usually indicates condylar resorption.

- •

If the asymmetry is progressive with skeletal, soft-tissue, and occlusal changes, then it is likely caused by TMJ pathology or a tumor.

DIAGNOSTIC AND TREATMENT FACTORS TO CONSIDER

Accurate diagnosis of the cause of the facial asymmetry is important for treatment planning. If the causative factor is not identified and addressed, then stability, function, and pain factors may be unpredictable, with asymmetry redeveloping.

TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT AND FACIAL ASYMMETRY

TMJ disorders and pathology are common causative factors or results of facial asymmetries, particularly affecting the mandible, and certain pathologies can produce a progressive worsening of the asymmetry and malocclusion. TMJ-associated changes usually occur at a relatively slow rate, from minimal change to 4 to 5 mm or more per year depending on the nature of the pathology. Other TMJ conditions may only cause pain and/or dysfunction without worsening facial asymmetry but may still need to be addressed for optimal treatment outcomes. Condylar underdevelopment or condylar resorption can cause the mandible and face to be smaller on one side and shift toward the involved side. On the other hand, a unilateral condyle, mandible, and associated structures can over develop (enlarge), causing facial asymmetry. In such patients the relatively normal side may also develop TMJ pathology (e.g., articular disk dislocation, arthritis) from the increased loading of that joint created by the overdevelopment of the opposite side. Therefore, performing orthognathic surgery only and ignoring the TMJs during treatment or failing to render proper TMJ management could result in redevelopment of the asymmetry and malocclusion, worsening TMJ-associated symptoms including jaw dysfunction and pain.

The TMJs should always be evaluated in a patient with facial asymmetry to determine if they are the causative factor, are associated with a problem that has developed because of facial asymmetry, are associated with a coexisting pretreatment condition, or are normal and healthy joints. Approximately 25% of patients with TMJ pathology or disorders will be asymptomatic. These are the patients whose condition can be more troublesome because the TMJ pathology may not be recognized, and therefore not treated, resulting in a poor outcome with potential redevelopment of asymmetry by condylar and mandibular overdevelopment or condylar resorption as well as initiation of pain, headaches, and other TMJ symptoms. Other patients will have overt TMJ signs and symptoms that could include one or more of the following: progressive facial and occlusal changes; history (previous or current) of TMJ click, pop, or crepitus; decreased jaw function; myofascial pain; TMJ pain; headaches; neck, shoulder, or back pain; open bite (anterior, lateral, posterior); earaches; tinnitus; vertigo; or development of speech and airway problems. Therefore treating facial asymmetries will often require surgical management of the TMJ pathology in order to have a highly predictable and stable functional and esthetic outcome as well as a pain-free treatment result. Nonsurgical TMJ treatment (e.g., splints, physical therapy, chiropractic treatment, orthodontics, medications) may help the TMJ symptoms but will not stabilize and eliminate TMJ pathology (e.g., disk dislocation, arthritis, condylar resorption or overdevelopment) to withstand the increased TMJ loading that usually accompanies the orthognathic surgery procedures necessary to achieve optimal functional and esthetic outcomes.

NUMBER AND TYPE OF PREVIOUS SURGERIES

The number of previous surgeries, particularly to the TMJ, may dictate the TMJ surgical procedure options. A patient with two or more previous TMJ surgeries will have a high failure rate if autogenous tissues are used for the TMJ reconstruction. A TMJ total joint prosthesis, such as the TMJ Concepts system (TMJ Concepts, Inc., Ventura, California) will have a much higher rate of success ( Figure 13-2 ). Patients with TMJ involvement of connective tissue and autoimmune diseases likewise may benefit from total joint prosthesis reconstruction because the disease processes will likely attack any autogenous tissues placed into the joint area but will not affect the total joint prostheses. Other end-stage TMJ conditions such as severe reactive arthritis or osteoarthritis, ankylosis, severe damage from trauma, failed TMJ alloplastic implants, and so on, particularly in adolescent or older age groups, will get the most predictable results with total joint prostheses and fat grafts packed around the articulating components of the prostheses.

The selection of the TMJ total joint prosthesis system is an important factor in treatment outcomes. Prostheses must have biocompatible and functionally compatible materials with a low wear coefficient, a posterior stop on the fossa, and components firmly fixed to the fossa and ramus with osseointegration and ideally would be custom-fitted devices. The downside to total joint prostheses is that it is unknown how long the systems will last. I have placed more than 550 TMJ Concepts total joint prostheses, with the longest follow-ups being at 19 years. No devices have been replaced because they wore out.

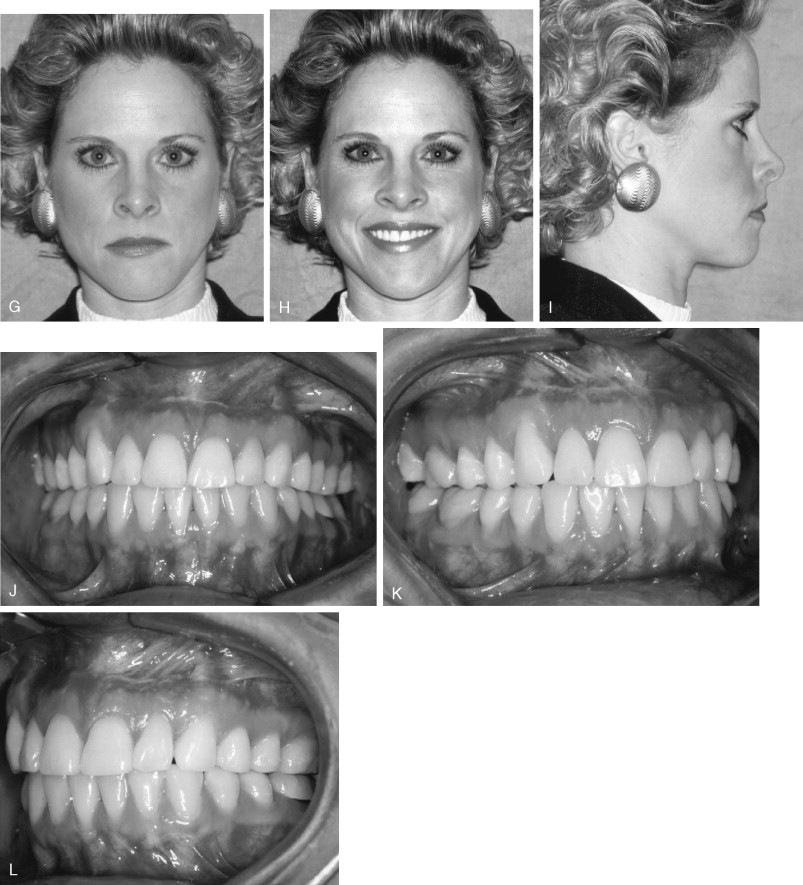

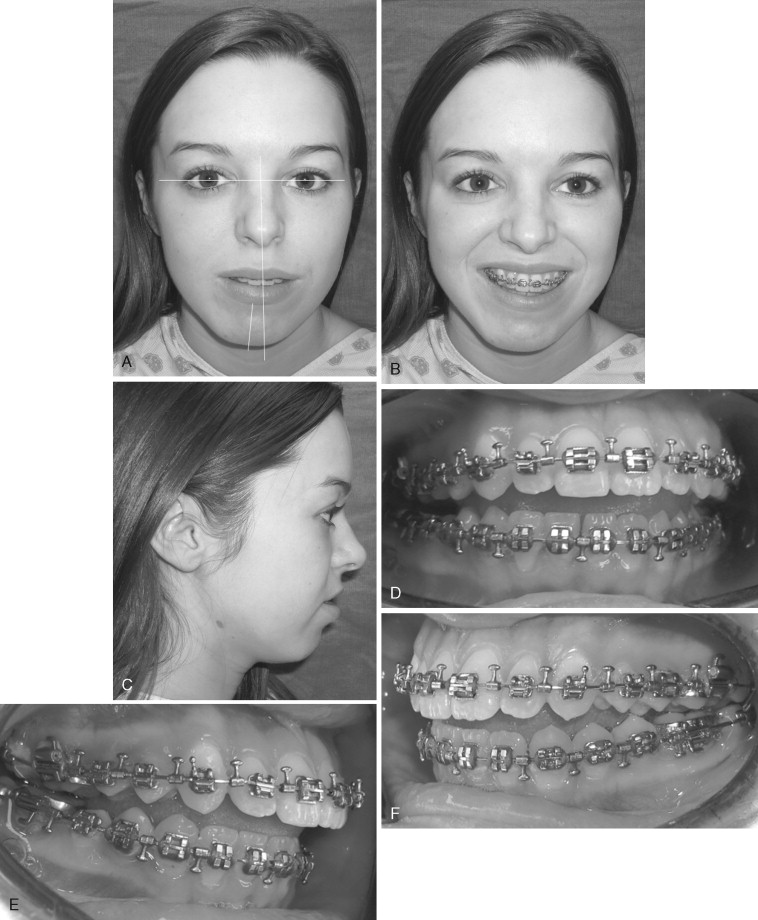

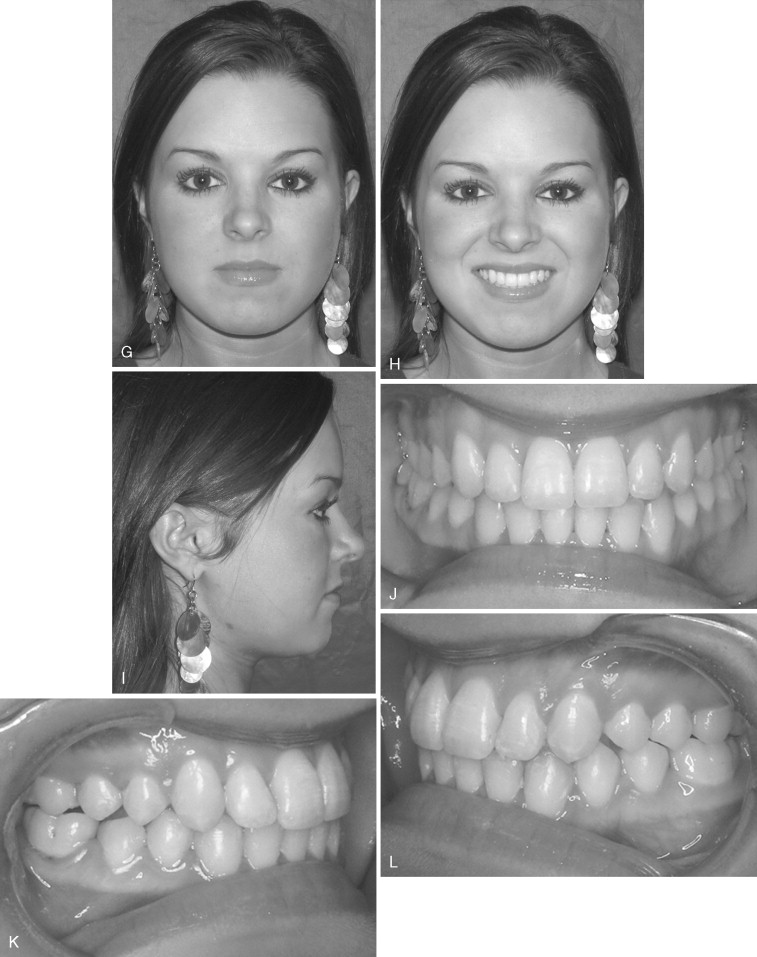

Patients with current or previous history of TMJ clicking or popping, TMJ pain, headaches, myofascial pain, ear symptoms, and so on related to TMJ articular disk dislocation who have undergone no or one previous TMJ surgery may benefit by articular disk repositioning and ligament repair with Mitek anchors (DePuy Mitek, Raynham, MA) to achieve a stable treatment outcome ( Figure 13-3 ).

An orthognathic surgery patient who initially has a good treatment result but subsequently develops facial asymmetry probably had a presurgical, unrecognized, and untreated TMJ pathologic condition. TMJ surgical intervention may be necessary to correct the pathology, in addition to repeat orthog nathic surgery, in order to achieve a high-quality stable result and pain-free outcome. A patient who may have vascular compromise to the maxilla or mandible from too many previous surgeries, smoking, or radiation therapy may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy presurgery to improve the vascularity and success rate.

PROGRESSION OF FACIAL AND OCCLUSAL CHANGES

It is important from a diagnostic and treatment planning standpoint to determine whether the facial asymmetry and occlusion are stable and static and whether the asymmetry and malocclusion are the result of a sudden change (immediate occurrence or within a few weeks) or if progressive changes are ongoing (slower continuous development that may take a few months to several years to identify). For predictable treatment outcomes, the TMJs must be stable, healthy, and free of pathology, or the asymmetry and malocclusion may redevelop and pain may occur after surgery.

Stable and static dynamics means there have been no active changes or progression whatsoever in facial asymmetry and occlusion for a minimum of 1 year. A stable static facial structure and occlusion without evidence of tumor or TMJ disorder or pathology and symptoms may indicate that the TMJ is not involved or at least not active in the current status of the facial asymmetry. However, in facial asymmetry the TMJs must still be thoroughly evaluated, as the TMJ pathology may merely be in a state of remission and could be reinitiated by TMJ stress and loading that will occur as the facial asymmetry is surgically corrected. If the facial asymmetry is stable and unchanging and there is no evidence of TMJ pathology or symptoms, then the asymmetry can be corrected with orthognathic surgery only, without TMJ surgery.

Sudden change indicates that abrupt development of facial and/or occlusal asymmetry has occurred, usually as a result of trauma, infection, condylar dislocation, neurologic or neuromuscular disorder, abnormal jaw posturing, poor orthognathic surgery outcome, and so on. The cause and associated deformities must be identified and appropriately corrected.

Progressive change indicates active pathology causing continued change usually as a result of TMJ disorders or pathology, tumor, growth variance, or tissue hypertrophy or atrophy. Progressive change generally indicates an active disease process or growth abnormality that may require additional procedures besides the orthognathic surgery to achieve stable predictable results. If the asymmetry is related to TMJ pathology, then TMJ surgery may be indicated in order to establish a stable, predictable, and pain-free outcome. Commonly observed progressive asymmetric changes include the following:

- •

Facial asymmetry that develops or significantly worsens from the early teen years or later in life is likely related to TMJ pathology or tumor.

- •

Progressively worsening unilateral Class III occlusal relationship with a contralateral cross-bite and shift of the mandible and chin to the opposite side may indicate a unilateral condylar hyperplasia (CH).

- •

Progressively worsening unilateral vertical lengthening of the face and jaws with lateral open bite on the involved side, usually with a Class I occlusion but with a significant transverse cant to the occlusion and face, usually indicates a unilateral mandibular condylar osteochondroma or osteoma.

- •

Development and progressive worsening of an anterior open bite and Class II occlusion usually indicates condylar resorption.

- •

If the asymmetry is progressive with skeletal, soft-tissue, and occlusal changes, then it is likely caused by TMJ pathology or a tumor.

PRESURGICAL PATIENT PREPARATION

Correction of facial and occlusal asymmetry will usually require orthognathic surgery and some cases will also require TMJ procedures. Presurgical and postsurgical orthodontic management is usually necessary to achieve the best treatment outcome. Also, the surgical sequencing is important if the best treatment results are to be achieved.

PRESURGICAL AND POSTSURGICAL ORTHODONTICS FOR FACIAL ASYMMETRY

The basic presurgical orthodontic goals are to align and level the teeth over the basal bone and remove dental compensations, regardless of the magnitude of the maxillary and mandibular malalignment. I have previously published detailed reports of presurgical orthodontic management of orthognathic surgery patients. Also, Chapter 19 in Volume III details the specifics for patient management after orthognathic and TMJ surgery.

DENTAL MODEL SURGERY

Facebow transfers for mounting the dental models on an anatomic articulator may be very inaccurate and not representative of the true jaw position relative to the cranial base. In asymmetric cases the inaccuracy may be even greater, rendering the dental model mounting and model surgery incorrect, thus adversely affecting the treatment outcome. Use of the SAM Occlusal Plane Indicator (OPI) (SAM-Prazisionstechnik, Munchen, Germany; U.S. distributor Great Lakes Orthodontics, LTD, Tonawanda, New York) is a significantly more accurate method for mounting dental models than facebow transfer, to best simulate the patient’s specific asymmetry. Based on cephalometric analysis and clinical assessment, the OPI platform can be set to include the occlusal plane angle, transverse cant, midline alignment, and yaw for mounting the maxillary model on the anatomic articulator of the clinician’s choice. The mandibular model can then be mounted with a TMJ centric relation position bite registration. Accurate model surgery can then be performed to simulate the surgery and construct the surgical splints.

AGE FOR SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Facial asymmetry may be affected by growth, with some conditions getting worse with growth and development. Predicting results and limiting correction of the jaw and TMJ-related deformities to one major operation can usually best be achieved by waiting until growth is relatively complete. Although there are individual variations, girls usually have the majority of their facial growth (98%) complete by the age of 15 years and boys by the age of 17 to 18 years. Because left-to-right asymmetric growth is common and some required surgical procedures may have an adverse effect on subsequent facial growth, performing surgery at earlier ages may result in the need for additional surgery at a later time to correct asymmetry and malocclusion that may develop during the completion of growth. There are definite indications for early surgery, such as ankylosis, growth center transplants (e.g., rib or sternoclavicular grafts), masticatory dysfunction, tumor removal, and airway obstruction. Wolford and colleagues have previously published reports on maxillary and mandibular surgery and the effects on growth, with guidelines for age at which surgical intervention is considered.

SURGICAL SEQUENCING

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses