This case report describes the importance of eliminating transverse dental compensation during preoperative orthodontic treatment for a patient with severe facial asymmetry. The patient, a 17-year-old Japanese woman, had severe facial asymmetry involving the maxilla and the mandible, and extreme transverse dental compensation of the anterior and posterior teeth in both arches. Therefore, the main treatment objectives were elimination of the transverse dental compensation by orthodontic treatment and correction of the morphology of the maxilla and the mandible by orthognathic surgery. The preoperative orthodontic treatment resulted in sufficient elimination of the transverse dental compensation and movement of the teeth into their proper positions so that basal bone firmly supported them. LeFort I osteotomy and sagittal split ramus osteotomy were performed to correct the skeletal morphology. Facial asymmetry was dramatically improved, and a favorable occlusion was obtained. At 1 year 8 months after the surgical orthodontic treatment, the facial symmetry and occlusion remained favorable. The results suggest that sufficient elimination of transverse dental compensation in the maxillary and mandibular arches during preoperative orthodontic treatment is requisite for successful treatment of severe facial asymmetry.

Facial asymmetry is highly visible, can degrade quality of life, and is often a chief complaint of orthodontic patients. Patients with severe facial asymmetry are generally treated with a combination of orthodontic and orthognathic surgical therapies, not only to improve their occlusion, but also to improve their facial esthetics. With such treatment, it is difficult to develop a plan to improve facial esthetics, because patients with severe facial asymmetry also often have extreme transverse dental compensation. The maxillary incisors and posterior teeth are usually inclined to the deviated side, and the mandibular incisors and posterior teeth are inclined to the contralateral side to maintain normal interarch positioning under transverse jaw relationships. In such cases, it is critical to eliminate the extreme transverse dental compensation of the maxillary and mandibular teeth and move them back to the proper positions for basal bones to firmly support them. If this is inadequately done, it will be impossible to obtain sufficient correction of the asymmetry and the occlusion.

We treated a patient with severe facial asymmetry, using orthodontic and orthognathic approaches, and improved her quality of life.

Diagnosis and etiology

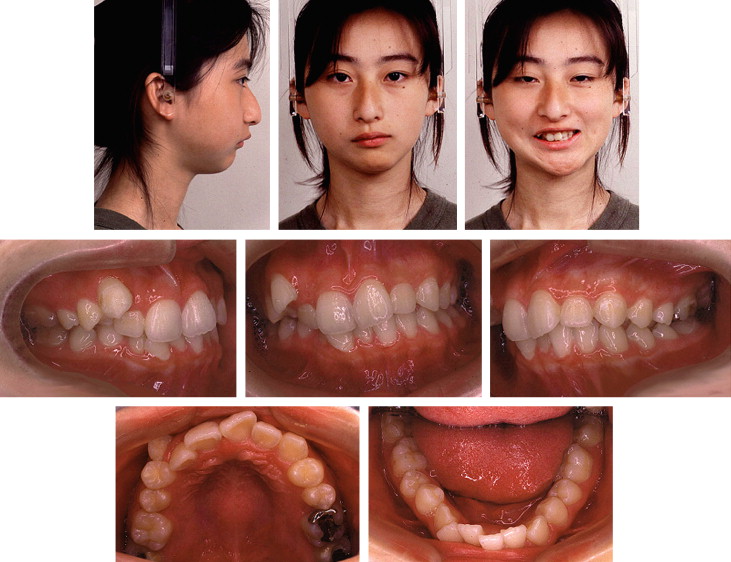

The patient was a 17-year-old Japanese woman. Her chief complaint was facial asymmetry. According to the interview, the facial asymmetry was pointed out by her family doctor and first became obvious when she was about 11 years old. Because there was no history of injury to her head or the jaw, and no relevant family history, the cause of her facial asymmetry was unknown. In the frontal view, severe facial asymmetry was obvious; the mandible was deviated to the left. In the lateral view, a convex facial profile was noted ( Fig 1 ).

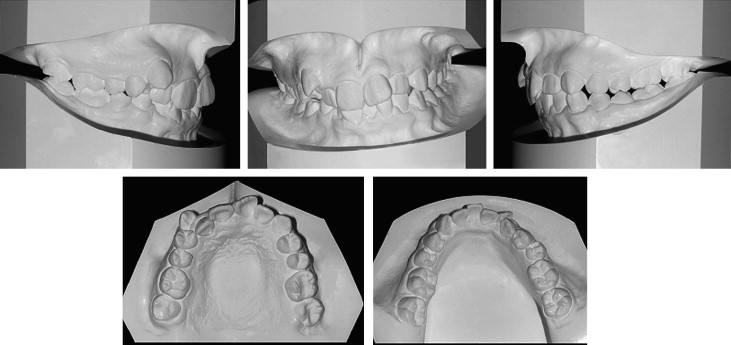

The midline of the maxillary arch was deviated about 1 mm to the right from the facial midline, whereas the midline of the mandibular arch was deviated 3 mm to the left ( Fig 2 ). The maxillary incisors were inclined to the left, and the mandibular incisors were inclined to the right. Overbite and overjet were 4.5 and 4.0 mm, respectively. The maxillary right canine was blocked labially, and a scissors-bite was observed between the maxillary and mandibular right first premolars. The molar relationships were Class I on the right and Class II on the left. The mandibular arch was asymmetric, with severe lingual inclination of the mandibular left molars and premolars. In contrast, the maxillary right molars had an extreme palatal inclination. There was moderate crowding in both arches, and the maxillary and mandibular arch-length discrepancies were –9 and –6 mm, respectively.

The patient had no temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder symptoms at the examination, although she had a history of occasional clicking sounds in the left TMJ. Magnetic resonance imaging showed anterior articular disc displacement without reduction, and computed tomography (CT) showed osteoarthrosis in the left TMJ.

A panoramic radiograph showed that the maxillary central incisors had short roots. No pathologic lesions of the alveolar bone were observed ( Fig 3 ). Lateral cephalometric evaluation showed a skeletal Class II jaw relationship (ANB, 8.1°) with mandibular retrognathia (SNB, 72.3°). The mandibular plane angle was steep, and the ramus was retroclined. The maxillary and mandibular central incisors were inclined lingually ( Table ). Both the maxilla and the mandible exhibited severe deviation on the frontal cephalogram and the 3D CT image ( Fig 3 ). Menton was deviated to the left 12 mm from the midsagittal plane (facial midline). The difference in height between the left and right molars was 5 mm, and the cant of the occlusal plane was 4.5°. The patient was diagnosed with a transverse jaw deformity of the maxilla and mandible with skeletal Class II jaw relationship.

| Norm (SD) | Pretreatment (17 y 3 mo) | Posttreatment (20 y 7 mo) | Postretention (22 y 3 mo) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angular (°) | ||||

| SNA | 81.3 (3.0) | 80.4 | 80.0 | 79.8 |

| SNB | 79.2 (3.0) | 72.3 | 74.0 | 73.9 |

| ANB | 2.1 (2.1) | 8.1 | 6.0 | 5.9 |

| Facial angle | 87.3 (3.1) | 80.5 | 82.0 | 81.9 |

| FMA | 27.1 (5.2) | 39.8 | 40.0 | 39.8 |

| U1-SN | 104.3 (5.8) | 83.8 | 94.0 | 94.8 |

| FMIA | 58.0 (6.0) | 51.9 | 51.5 | 52.5 |

| IMPA | 93.0 (6.2) | 88.3 | 87.5 | 88.0 |

| Linear (mm) | ||||

| A′-Ptm′ | 50.1 (3.2) | 46.7 | 46.2 | 46.0 |

| Gn-Cd | 120.8 (5.2) | 105.9 | 109.3 | 109.3 |

| Pog′-Go | 80.0 (4.7) | 70.5 | 71.7 | 71.6 |

| Cd-Go | 61.2 (4.3) | 49.9 | 52.1 | 52.0 |

Treatment objectives

The following treatment objectives were established: (1) correct the jaw deformities of the maxilla and the mandible; (2) eliminate the transverse dental compensation; (3) coordinate the skeletal and dental midlines; (4) correct and coordinate the maxillary and mandibular arch forms; (5) correct the irregularity of the teeth (eliminate the arch-length discrepancy); and (7) improve the facial asymmetry.

Treatment objectives

The following treatment objectives were established: (1) correct the jaw deformities of the maxilla and the mandible; (2) eliminate the transverse dental compensation; (3) coordinate the skeletal and dental midlines; (4) correct and coordinate the maxillary and mandibular arch forms; (5) correct the irregularity of the teeth (eliminate the arch-length discrepancy); and (7) improve the facial asymmetry.

Treatment alternatives

Several treatment options were considered. The first was extraction of the maxillary and mandibular first premolars during preoperative orthodontic treatment. This option would make it easy to coordinate the maxillary and mandibular arch forms. But coordinating the dental midline with the skeletal midline of the mandible would be difficult. In this option, facial asymmetry would be difficult to correct during the orthognathic surgery. The second option was extraction of the maxillary first premolars and the mandibular left first premolar. Although this option might cause a Class II molar relationship on the right side, it would be beneficial for eliminating the transverse dental compensation of mandibular incisors and coordinating the dental midline with the skeletal midline of mandible.

The first surgical option was a mandibular osteotomy only. The second option was 2-jaw surgery: Le Fort I and mandibular osteotomies. The first option would not sufficiently improve the facial asymmetry, although the surgical intervention was limited to the mandible. On the other hand, 2-jaw surgery would be much more effective for improving the facial symmetry of the maxilla and the mandible.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses