Introduction

Headgears have been used to treat Class II malocclusions for over a century. The purpose of this retrospective study was to investigate the profile esthetic changes resulting from headgear use in growing Class II patients with protrusive, normal, and retrusive maxillae.

Methods

Profile silhouettes were created from pretreatment and posttreatment lateral cephalometric tracings of growing Class II patients treated with headgear followed by conventional fixed appliances. Ten patients had an initially protrusive maxilla (FH:NA, >92°), 10 had an initially normally positioned maxilla (FH:NA, 88°-92°), and 10 had an initially retrusive maxilla (FH:NA, <88°). A panel of 20 laypersons judged the profile esthetics of the randomly sorted silhouettes. Descriptive statistics, correlation analysis, and anlaysis of variance (ANOVA) with post-hoc Tukey-Kramer tests were used to ascertain differences between groups and the effects of treatment.

Results

A significant moderate correlation was found between initial ANB magnitude and the improvement in profile esthetic score with treatment (r = 0.49, P <0.01). No significant correlations were found between the initial anteroposterior position of the maxilla (FH:NA) and the initial, final, or change in profile esthetic scores. There were average improvements with headgear treatment in profile esthetics for all groups.

Conclusions

In Class II growing patients with protrusive, normally positioned, or retrusive maxillae, headgear treatment used with fixed orthodontic appliances is effective in improving facial profile esthetics: the greater the initial ANB angle, the greater the profile esthetic improvement with treatment.

Class II malocclusions are relatively common in the general population and make up a significant percentage of patients treated by orthodontists. Ast et al examined the occlusions of 1418 high school students aged 15 to 18 years from upstate New York and reported that 23.8% had a Class II malocclusion; there was a ratio of Class II to Class I malocclusions of 1:3. In their sample, Trottman and Elsbach found that 7% of black children and 14% of white children had a Class II malocclusion. Silva and Kang reported that Latinos had a prevalence of 21.5%.

Of the 3 approaches to skeletal Class II treatment (orthopedics, masking or camouflage, and surgery), conventional wisdom suggests that, “In theory, functional appliances stimulate and enhance mandibular growth, while headgear retards maxillary growth—so functional appliances would seem to be an obvious choice for treatment of mandibular deficiency, and headgear an equally obvious choice for maxillary excess.” Is this correct? Are functional appliances the obvious choice to enhance mandibular growth and headgears the obvious choice for Class II patients with protrusive maxillae?

Recently, the American Association of Orthodontists’ Council on Scientific Affairs conducted a review of the best scientific evidence available and concluded that, in the long term, there is no evidence that functional appliances increase horizontal mandibular growth. So, functional appliances are not necessarily the obvious choice for mandibular deficiency. In a comparison of Herbst and headgear treatment involving matched growing Class II Division 1 patients, both the Herbst and headgear groups had similar occlusal corrections and resulted in similarly attractive profiles.

What about the use of headgears? Specifically, is headgear the treatment of choice for protrusive maxillae, and is its use contraindicated in patients with normal or even deficient maxillae? Will headgear use in such patients result in adverse esthetic changes?

Headgears have been used to treat Class II growing patients since the late 1800s, and studies have shown that the effects of cervical-pull facebow headgears differ from the effects of high-pull facebow headgears. Firouz et al determined that high-pull headgears inhibit horizontal and vertical maxillary growth, and maxillary first molars are concurrently moved distally and intruded with a force directed through their center of resistance. High-pull headgears are traditionally used for treating Class II patients with a steep mandibular plane because these patients need minimized molar extrusion and downward and forward growth of the maxilla. Cervical-pull headgears, on the other hand, inhibit forward growth of the maxilla, tip the palatal plane of the maxilla clockwise slightly, increase eruption of the maxillary molars slightly, and distalize the maxillary first molars. Cervical-pull headgears are traditionally used for treating Class II patients with a flat mandibular plane and a short lower anterior face height.

An evaluation of pretreatment and posttreatment soft-tissue profiles was conducted on growing Class II Division 1 patients treated with headgear and fixed orthodontic appliances. One hundred patients were grouped according to the severity of their initial retrognathia and vertical skeletal status. The pretreatment and posttreatment profile silhouettes of each patient were scored. Whereas patients with initially greater skeletal discrepancies were judged to be less attractive initially, these patients also had the greatest improvement, so that there was no perceived difference in final scores between the groups.

Absent from the literature are comparisons of the profile esthetic changes resulting from headgear use in growing Class II patients with protrusive, normal, or deficient maxillae (anteroposterior dimension). The purpose of this retrospective study was to investigate these esthetic changes.

Material and methods

An exhaustive search was conducted in the University of Iowa’s Department of Orthodontics to identify records of patients treated with headgear and having the widest range of initial maxillary anteroposterior positioning. Inclusion criteria were initial and posttreatment lateral cephalometric radiographs and models, initial bilateral Class II molar relationships of end-on to full step, and treatment during adolescence to a Class I molar relationship with headgear and fixed orthodontic appliances. All patients were treated without extractions. Headgear type mirrored the usual application found in clinical practice—high-pull headgears were generally used in growing Class II patients with steeper mandibular plane angles, and cervical-pull headgears were used in patients with flatter mandibular plane angles.

The subjects were divided into 3 groups based on maxillary anteroposterior position. Ten subjects were identified as having an initially protrusive maxilla (FH:NA, >92°), and 10 had an initially retrusive maxilla (FH:NA, <88°). Of the over 100 patients identified as having an initially normally positioned maxilla (FH:NA, 88°-92°), 10 patients were randomly chosen to comprise a normal group. High-pull headgears, cervical-pull headgears, and combination high-pull plus cervical-pull headgears were used in 54%, 19%, and 27% of the patients, respectively.

The initial and final lateral cephalometric radiographs of all subjects were traced on matte acetate tracing film. Linear and angular measurements were made to the nearest 0.5 mm and 0.5°, respectively. The following points, planes, angles, and linear measurements were constructed for all initial and posttreatment tracings: Frankfort horizontal (FH), mandibular plane (MP), mandibular incisor tip (Ī-tip), ANB, SN:MP, FH:NA, 1:SN, Ī:FH, overbite, and overjet. Finally, the amounts that the right and left first molars were Class II (the horizontal, linear distance between the mandibular first molar’s mesiobuccal groove and the maxillary first molar’s buccal cusp tip) were measured on the initial and final models.

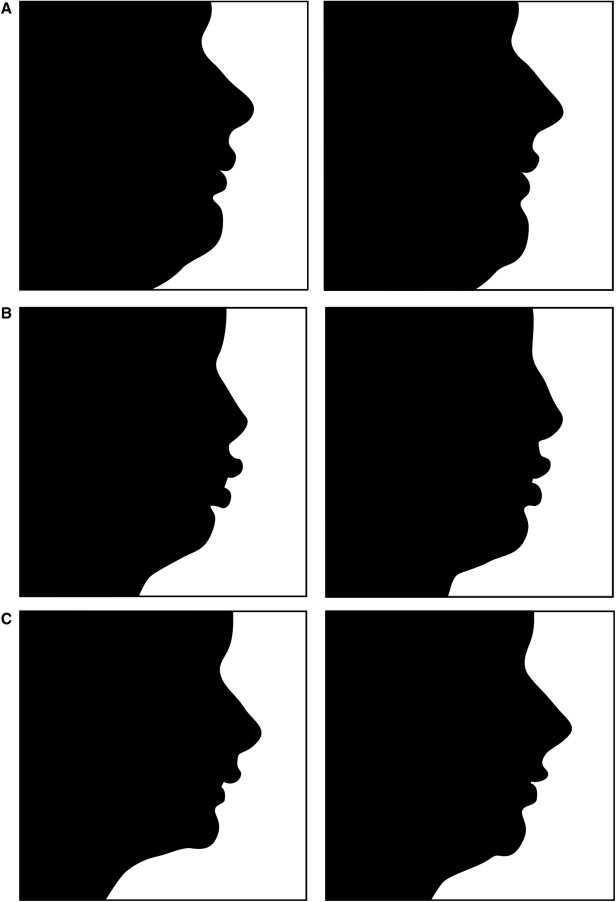

Following the method described previously, pretreatment and posttreatment lateral cephalometric tracings were used to produce solid black silhouettes labeled with identification numbers only. The tracings were scanned into Photoshop (version 7.0, Adobe Systems, San Jose, Calif) by using a ScanMaker (9800XL, Microtek USA, Carson, Calif) set to gray scale with a resolution of 300 dpi and saved as JPEG images. Each line tracing was rotated so that the FH was parallel to the horizontal and converted into solid black silhouettes by using CorelDraw (Corel, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). All silhouettes were oriented to the center of the image with the FH plane parallel to the base of the image, all silhouettes extended from above soft-tissue glabella to just below the throat point, and the distance from soft-tissue glabella to soft-tissue pogonion was standardized for each profile ( Fig ).

To create the profile judging presentation, the silhouettes were transferred into software (Windows PowerPoint, Microsoft, Redmond, Wash) and placed in random order. To ascertain intraobserver reliability, half of the silhouettes were randomized again and placed at the end of the first set of silhouettes. Each image silhouette was labeled with a sequential number to assist the evaluators, and these numbers were cross-referenced with the specific initial or final profile. After we instructed the panel of judges, 6 introductory profile images from an earlier study were first presented to familiarize the evaluators with the procedure. The actual presentation was then continued with 10-second intervals for each profile silhouette to be evaluated. The panel of evaluators consisted of 20 laypersons (10 women, 10 men) whose ages ranged from 25 to 52 years. They were asked to evaluate each profile silhouette and assign an attractiveness score to it using a Likert scale from 1 (very unattractive) to 7 (very attractive).

To ascertain reliability, initial lateral cephalometric, final cephalometric, and cast measurements of 4 randomly selected subjects (13% of the original sample) were remeasured. The paired-sample t test was used to determine whether the mean measurement difference between the 2 measurements significantly differed from zero. Intraclass correlation was also computed as a measure of intraobserver agreement between the first and second rating scores of 1 judge. No statistically significant difference was found between the first and second measurements ( P <0.8205). Furthermore, there was strong evidence that the moderate intraclass correlations for all judges (0.72), female judges (0.71), and male judges (0.74) differed from zero ( P <0.0001).

Descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and minimum and maximum values for each cast measurement; angular and linear cephalometric measurements; and profile esthetic scores were calculated. Pearson correlations and Spearman rank correlations were calculated to determine relationships between profile esthetic rankings and cast or cephalometric measurements. A 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post-hoc Tukey-Kramer test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference between the 3 maxillary position groups in terms of average initial esthetic profile scores, average final esthetic profile scores, change in average esthetic profile scores, and change in cephalometric and cast measurements. Because of the lack of normality in some cases, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test, followed by the Bonferroni post-hoc test, was also conducted. A paired-sample t test was used to compare the initial and final profile esthetic scores. A 0.05 level of statistical significance was set, and SAS software for Windows (version 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for the data analysis.

Results

A significant moderate correlation was found between initial ANB magnitude and the improvement in profile esthetic score with headgear treatment (r = 0.49, P = 0.0054), but no significant correlations were found between initial anteroposterior position of the maxilla (FH:NA) and initial, final, or change in profile esthetic score. No significant correlations were found between the initial anteroposterior position of the maxilla and any other variables examined.

In terms of initial, or pretreatment findings, no statistically significant differences were found between maxillary protrusive, normal, and retrusive groups in terms of initial profile esthetic scores, age, sex, Class II discrepancy (right or left), average right and left Class II discrepancy, SN:MP, 1:SN, Ī:FH, overbite, or overjet ( Table I ). As expected, the 1-way ANOVA and the Tukey-Kramer test indicated that the mean initial FH:NA value in the protrusive group was significantly greater than that observed in the normal and retrusive groups, whereas the mean initial FH:NA in the normal group was greater than that in the retrusive group. The Tukey-Kramer test indicated that the mean initial ANB value observed in the protrusive group was significantly greater than that in the retrusive group. However, there were no significant differences in mean initial ANB values between the protrusive and normal groups, and between the normal and retrusive groups.

| Variable | Protrusive maxilla group (n = 10) | Normal maxilla group (n = 10) | Retrusive maxilla group (n = 10) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 10.75 (0.90) | 10.62 (1.06) | 10.87 (1.28) | NS |

| Esthetic score | 3.07 (1.16) | 2.83 (0.84) | 3.31 (0.88) | NS |

| SNA (°) | 85.70 (2.65) A | 83.00 (1.91) A | 78.50 (3.53) B | 0.0001 ∗ |

| SNB (°) | 79.00 (2.29) A | 77.50 (1.70) A | 74.32 (2.67) B | 0.0001 ∗ |

| ANB (°) | 6.70 (1.44) A | 5.50 (1.00) A,B | 4.18 (1.50) B | 0.0008 ∗ |

| SN:MP (°) | 31.05 (4.61) | 30.95 (3.76) | 31.36 (3.90) | NS |

| FH:NA (°) | 94.30 (1.58) A | 90.45 (1.42) B | 84.68 (2.61) C | 0.0001 ∗ |

| 1 :SN (°) | 104.95 (4.00) | 106.30 (5.65) | 105.18 (7.49) | NS |

| Ī:FH (°) | 52.05 (5.58) | 59.95 (3.81) | 59.59 (7.64) | NS |

| Overjet (mm) | 6.95 (2.05) | 7.75 (2.63) | 7.68 (2.46) | NS |

| Overbite (mm) | 5.75 (1.59) | 5.05 (2.41) | 6.23 (1.63) | NS |

| Class II right (mm) | 3.45 (0.96) | 4.10 (1.10) | 4.14 (1.14) | NS |

| Class II left (mm) | 3.95 (1.23) | 3.95 (1.04) | 4.18 (1.27) | NS |

| Average class (mm) | 3.70 (0.81) | 4.03 (0.92) | 4.16 (1.09) | NS |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses