Sequelae and Complications of Surgical Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment: Botulinum Toxin Injection

Introduction

The treatment of drooling is a therapeutic problem that remains unsolved in children who present mainly with severe neurological disorders. Because posterior drooling is constant and continuous, these young patients are at high risk for developing life-threatening pulmonary infections, as they often suffer dysphagia and aspiration and have associated neuromuscular dysfunctions. The families, parents, and relatives of the affected children suffer severe everyday stress and the associated social isolation.

Treatment for drooling was until recently a domain for surgery that involved excision of the major salivary glands or transposition of their excretory ducts, or other options such as surgery on the tympanic plexus and/or chorda tympani, to achieve a reduction or ablation of the secretomotor fibers and turn off salivary stimulation.1–3 All of these invasive procedures are stressful, particularly for children and young adults, and because of the doubtful prognosis of the basic disease, surgery was rarely indicated because of the unpredictable results and possible side effects. Oral systemic anticholinergic therapy in the form of a daily tablet or elixir medication, although pharmacologically effective in reducing saliva production, is contraindicated for prolonged periods due to its possible side effects on the circulatory system.

A new therapeutic approach using topical intraglandular injection of botulinum toxin A has been introduced during the last 10 years. This nonsurgical approach was based on the hypothesis, supported by several publications including clinical observations and animal experiments, that botulinum toxin might successfully achieve prolonged reduction of salivary flow in neurological and other otorhinolaryngological disorders and diseases. This nonsurgical treatment option has led to the patients suffering far less stress in comparison with similar patients who required surgical procedures in the past.

Definition

Drooling, or salivary incontinence, is characterized by unwanted and continuous diurnal or nocturnal loss of saliva from the oral cavity. It is important to distinguish drooling from sialorrhea, which refers to a relative or absolute overproduction of saliva. In contrast, the amount or volume of salivation is within the normal range in patients who drool.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Drooling may result from neuromuscular dysfunction, sensory dysfunction, or an anatomic (motor) dysfunction. The most common cause identified is a neuromuscular dysfunction. In children, mental retardation and cerebral palsy are commonly implicated; in adults, Parkinson disease is the most common etiology.4 Pseudobulbar palsy, bulbar palsy, and strokes are less common causes. Isolated episodes and occasional periods of drooling in infants and toddlers are normal and unlikely to be a sign of either disease or complications. Drooling is frequently associated with the teething period. Drooling in infants and young children may also be associated with episodes of upper respiratory infections and periods of nasal allergy. However, it is important that drooling may also present during an early phase in children with early signs of a neurological disorder and also in patients with undiagnosed developmental delay.

The reasons for excessive drooling appear to be related firstly to the patients being unaware of the build-up of saliva in the mouth; secondly, to an inability to perform frequent swallowing actions; and thirdly, to an inefficient swallowing mechanism. The treatments for excessive drooling are related to these causes: firstly, making the patient aware of the mouth and its functioning; secondly, encouraging the patient to increase the frequency of swallowing during the day; and thirdly, enabling the patient to resume conscious swallowing movements at frequent intervals between mealtimes. Although the causes of drooling in children may be varied and complex, it is necessary and important to offer a treatment plan for the symptom to patients and their parents, as drooling is not only an aesthetic problem but can lead to serious and possibly fatal conditions such as aspiration pneumonia. Many different treatment options are available for patients/children who suffer from drooling.

Clinical Features

Drooling is characterized by a continuous loss of saliva from the mouth. The resultant prolonged contact of saliva with the skin can lead to serious skin alterations, such as local infections or eczemas (Fig. 12.1). Patients who suffer from drooling are socially stigmatized. The drooling patient creates parental anxiety and social embarrassment, resulting in social isolation. In an ordinary social environment, people react when faced with a patient who is obviously drooling, and this can affect the patient’s own response to a social event, usually resulting in avoidance of such social confrontations. These occasions lead to avoidance of society and social isolation for the patients, who try to avoid social and public events. These difficulties are relevant not only for children, but also for adults who suffer from drooling.

Diagnostic Work-Up

Objective and subjective measures have been developed to quantify the symptoms of relative sialorrhea. The objective tests use one of two techniques. Radioisotope scanning and collecting cups attached to the patient’s chin are primarily used for research purposes and are therefore of limited relevance in everyday clinical work. A variety of subjective scales for sialorrhea have been compiled and validated. The numerical scales involved are useful for individual patient assessment and monitoring individual therapy. However, it is the impact of sialorrhea on the patient’s quality of life that is the most important factor in determining the necessity for and effectiveness of therapy or treatment interventions. Subjective psychological assessment of the patient and repeated visible loss of saliva from the mouth are therefore the most important parameters that have to be measured to asses the success of treatments.

Fig. 12.1 A child with massive drooling resulting from a neuro-pediatric disease involving an extensive swallowing disorder. Injection of botulinum toxin dramatically reduced the oral loss of saliva.

Another more quantitative method of measuring salivary flow is to collect the saliva using cotton-wool rolls over a period of 5 minutes (further details on measurement methods are given in Chapter 3). The saliva-soaked cotton balls can be centrifuged, and the volume of saliva is easily measured. A major advantage of this method is that the specimen obtained can undergo sialochemistry testing, which may result in a change in the patient’ s management.5

Differential Diagnosis

Drooling has a wide variety of causes, and patients therefore require a thorough physical examination. A systematic evaluation process is essential in order to reach a correct diagnosis and proceed with the subsequent management plan. Some patients may also have a neurological disorder such as infantile cerebral palsy (ICP) or anterior opercular syndrome (AOS). These patients have to be distinguished from an etiologically very different group of patients in whom saliva production is also adequate, but who are unable to transport the saliva into the pharynx due to paresis of the pharyngeal muscles, or who have a disease involving the swallowing mechanism itself. There may also be patients with an organic or physical obstruction of the pharynx or esophagus, such as strictures, scars, or more rarely a benign or malignant neoplasm.

Infantile Cerebral Palsy

Infantile Cerebral Palsy

Patients with infantile cerebral palsy (ICP) have a normal and intact swallowing reflex, but with a reduced capacity to control the initial voluntary preparatory phase of swallowing, and they are also unable to activate a coordinated swallowing sequence. As a result, these patients have problems in coordinating swallowing and breathing. The lack of muscular coordination and altered swallowing sequence results in the mouth filling with saliva, resulting in pooling and anterior spillage of saliva (anterior drooling) or uncoordinated swallowing (posterior drooling). Thus, the majority of these patients are not suffering from an absolute overproduction of saliva, but rather from relative hypersalivation.

Anterior Opercular Syndrome

Anterior Opercular Syndrome

Characteristically, patients with anterior opercular syndrome (AOS), also known as Foix–Chavany–Marie syndrome, are not able to perform voluntary movements of the face, jaw, tongue, and pharynx. As a result, they are unable to speak, swallow, grimace, smile, or carry out any voluntary facial masticatory or linguopharyngeal movement. However, the involuntary responses in these groups of muscles are normal. Emotions and reflex functions such as laughing, yawning, and coughing, as well as other mimicking movements accompanying emotions, eye closure during sleep, and the blink reflex are unaffected. The anatomic substrate for this voluntary–involuntary dissociation is a bilateral lesion of the frontoparietal operculum, usually caused by cerebrovascular accidents. The prognosis is usually poor, particularly with regard to the ability to speak and eat.

The two most frequent diseases responsible for drooling in children are infantile cerebral palsy and the anterior opercular syndrome. The major cause in adults is Parkinson disease.

The two most frequent diseases responsible for drooling in children are infantile cerebral palsy and the anterior opercular syndrome. The major cause in adults is Parkinson disease.

Surgical Treatment

Treatment for sialorrhea, or extensive relative hypersalivation contributing to drooling, is still an unsolved therapeutic problem in children who have chronic severe neurological diseases.

Treatment for sialorrhea, or extensive relative hypersalivation contributing to drooling, is still an unsolved therapeutic problem in children who have chronic severe neurological diseases.

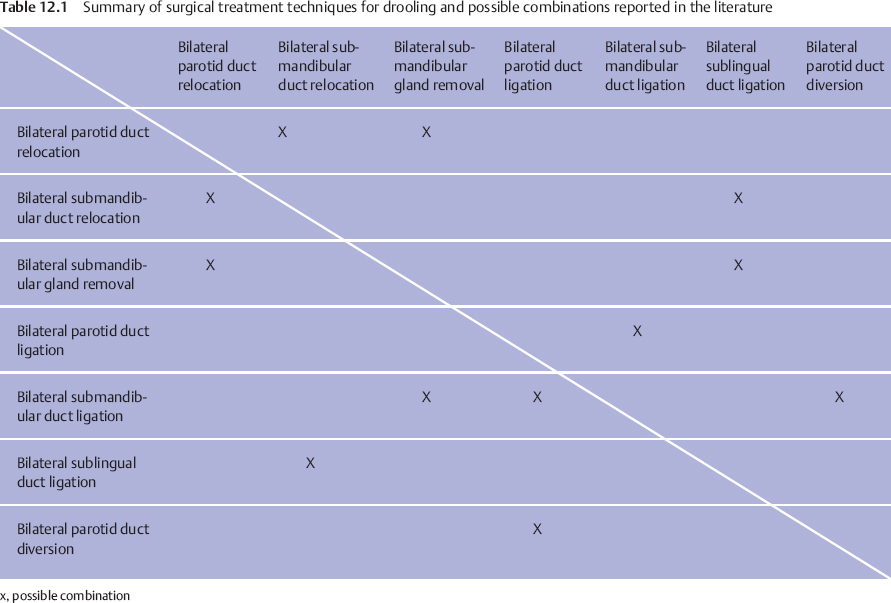

Surgical treatment is possible in certain cases, and various surgical procedures can be used.6–8 These range from interventions such as interrupting the autonomic nerve supply to the salivary glands, performing surgical procedures on the major salivary glands themselves, and diversion techniques performed on the parotid and submandibular salivary main duct system. All of the procedures described below can be used in various combinations. Table 12.1 summarizes the surgical procedures described and tabulates the combinations reported in the literature.

Neurectomy

Neurectomy

Neurectomy of the parasympathetic nerves supplying the salivary gland tissues can be carried out unilaterally or bilaterally by transecting the tympanic plexus or chorda tympani as it traverses the middle ear.

Physiological Background

The secretion of water and electrolytes by the major salivary glands is mainly regulated by parasympathetic nerves. Innervation of the parotid gland is controlled by the glossopharyngeal nerve (via the inferior salivatory nucleus, tympanic nerve, tympanic plexus, and lesser petrosal nerve), changing from preganglionic to postganglionic parasympathetic fibers within the otic ganglion. The parasympathetic innervation follows the auriculotemporal nerve leading into the parotid gland. Innervation of the submandibular and sublingual glands is controlled by the parasympathetic fibers, which have their origin in the superior salivatory nucleus and accompany the intermediate nerve and the chorda tympani. The parasympathetic fibers change from preganglionic to postganglionic parasympathetic fibers in the submandibular ganglion.9

In addition to the parasympathetic innervation of the major salivary glands, there is a direct sympathetic adrenergic innervation via the periarterial network of the salivary glands. This sympathetic innervation pathway is mainly responsible for the secretion of proteins. It can therefore be said that there is a double innervation pathway for the cephalic salivary glands, with the parasympathetic innervation being mainly responsible for the amount of saliva and the adrenergic part mainly being responsible for the content of the saliva.

Effects of Parasympathetic Denervation

Parasympathetic denervation of the major salivary glands leads to an immediate reduction in salivary gland secretion,9 the effects of which on salivary volume are noticeable within 2–3 weeks, but disappear after several months.1,3,10 An understanding of salivary neurology obviously shows that performing a tympanic neurectomy alone or in combination with division of the chorda tympani would be ineffective in producing permanent and long-term effects on drooling symptoms. In addition, surgical denervation can lead to uncontrolled spontaneous nerve sprouting at the lesion site, due to the high regeneration potential of the autonomic nerve system. This regeneration process can lead in the end to greater sensitivity to neurotransmitters (e.g., acetylcholine) in the transected organs.9 It should also be mentioned that transecting the chorda tympani on both sides leads to complete loss of taste on the anterior part of the tongue.

Duct Relocation

Duct Relocation

Duct relocation procedures can be carried out with the parotid and the submandibular main duct system.

Submandibular Duct Relocation

The aim in submandibular duct relocation is to move the duct and its ostium posteriorly into the oropharynx, usually into the tongue base. Relocation into the area of the posterior tongue supports the direct flow of saliva into the oropharyngeal space and may therefore help initiate the swallowing reflex. This mechanism will not work if the duct is relocated into the anterior pillar of the fauces (the palatoglossal arch), as often described, or a position more anterior in the oral cavity.

Relocation of the Parotid Duct

The aim in relocating the parotid duct is also to achieve a more posterior location of the ostium and duct than the natural position. In this procedure, the parotid ostium and duct are relocated into the tonsillar fossa or the posterior tonsillar pillar.

Duct Ligation

Duct Ligation

Ligation of the parotid and submandibular ducts has also been described as a single procedure, or as a combined procedure with both parotid and submandibular duct ligation. This is considered to be a simple procedure, and it can be performed transorally with relatively low complication rates.

Gland Removal

Gland Removal

Gland removal procedures have also been described. These mainly involve excision of both of the submandibular glands, which are the main contributors to resting salivary flow, without any stimulation. This type of surgical treatment is only appropriate in severe cases.

A well-established option is bilateral extirpation of the submandibular gland, combined with relocation of the parotid duct into the tonsillar folds; tonsillectomy is recommended in addition in patients with hyperplastic tonsils.11,12 This type of surgery is considered complex, as it is extremely stressful for the patient and is associated with several complications such as cyst formation, chronic parotitis, swelling of the cheeks due to duct stenosis caused by trauma, and overstretching of the newly positioned duct.10,12 When swallowing is disturbed due to additional malfunction of the upper esophageal sphincter,13 the danger of saliva aspiration needs to be borne in mind.14

Sequelae and Complications of Surgical Treatment

Sequelae and Complications of Surgical Treatment

Several complications following surgical procedures have been described,6–8 and various complication rates have been reported. Complication rates following surgery for drooling have been reported to be as high as 70%. In view of this serious and permanent risk of complications, indications for surgery should only be considered in patients with a persistent and long-term problem with drooling that has not responded to other nonsurgical forms of treatment. Surgery must not be carried out too early, when there is a possibility of improvement (e.g., in swallowing following a cerebrovascular accident), and conservative treatment must continue for a protracted period despite pressure from patients and their carers.

Typical complications:

Typical complications:

Relocation of the submandibular duct: hematomas, anterior dental caries, aspiration, ranulas, duct stenosis, and duct obstructions, additional surgery for persistent drooling, lateral neck cysts, and injury to the lingual nerve.

Relocation of the submandibular duct: hematomas, anterior dental caries, aspiration, ranulas, duct stenosis, and duct obstructions, additional surgery for persistent drooling, lateral neck cysts, and injury to the lingual nerve.

Relocation of the parotid duct: transient parotid swelling due to narrowing of the duct or due to duct stenosis, parotitis, sialoceles, as well as dental problems.

Relocation of the parotid duct: transient parotid swelling due to narrowing of the duct or due to duct stenosis, parotitis, sialoceles, as well as dental problems.

Ligation of the parotid duct: this may lead to hematomas, sialoceles, and infections in the parotid area.

Ligation of the parotid duct: this may lead to hematomas, sialoceles, and infections in the parotid area.

Gland excision: anterior dental caries, sialoceles, and injury to branches of the facial nerve.

Gland excision: anterior dental caries, sialoceles, and injury to branches of the facial nerve.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses