Though rare, malignancies of the orofacial region often have serious consequences. Malignancies of the orofacial region are typically discovered during a clinical examination or from a patient complaint. Initial discovery from a radiograph is rare. Three-dimensional imaging using advanced imaging techniques often provides adequate information about the aggressive nature of a lesion. Radiographically based imaging demonstrates mainly hard-tissue destruction and, rarely, bone deposition. MRI provides excellent visualization of soft-tissue densities without using ionizing radiation. Functional imaging is used to visualize increased metabolic activity associated with malignancies, and is excellent for determining the metastatic spread of a lesion.

Key points

- •

Malignancies often have serious consequences, including disfigurement and death.

- •

All radiographs should be examined for signs of malignant lesions.

- •

Characteristic appearances of malignant lesions include ill-defined borders, asymmetric appearance, destruction of adjacent bone and cortical borders, and radiolucency with pieces of trapped bone.

- •

All bony lesions should be visualized completely and, where possible, in 3 dimensions.

- •

Histopathologic examination is generally the gold standard for final diagnosis of malignant lesions.

Introduction

This article highlights the radiographic features of malignant lesions and presents the clinical correlations that may aid in the initial diagnosis of orofacial malignancies.

The word “malignant” comes from the Latin malignare , meaning “to act wickedly” ( mal = “bad”). Cancer appears when a stimulus triggers abnormal changes to the chromosomes within cells. The initial stage that can be detected by histopathologic examination is called dysplasia (abnormality) and there are multiple evolutionary stages known, such as carcinoma in situ, primary neoplasm, and secondary or metastatic neoplasm. Most changes take place at the subcellular level and manifest themselves as uncontrolled multiple cell divisions and persistence of old cells while young cells do not mature and differentiate. The clinically visible aspect is usually a late one, illustrated by the cancerous growth, tumor, or mass. It may be at this point that radiographically evident changes also occur.

In contrast to a benign lesion, a malignant tumor is characterized by uncontrolled growth potential, an aggressive and invasive nature, and the ability to metastasize. If a tumor arises de novo it is called a primary tumor, and if it originates from a distant tumor it is referred to as secondary or metastatic. Metastases share the tissues of the primary tumor, but they occur in a different and, frequently, distant location. Metastases illustrate the spread of cancer cells, usually traveling through the blood or lymph vessels, and can invade and develop in any other anatomic region. Often, the first site of neoplastic invasion is the nearby lymph nodes.

According to the National Cancer Institute, “head and neck cancers, which include cancers of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, salivary glands and nose/nasal passages, account for 3% of all malignancies in the US.” Cancers of the oral cavity represent 85% of all head and neck cancers, the eighth most common malignancy in males and 15th most common in females. Estimates for 2015 are far from gratifying. The Oral Cancer Foundation and American Cancer Society estimate in 2015 that 43,000 to 45,000 new cases of oral and oropharyngeal cancers with 8000 to 8650 deaths (approximately 1 per hour) will occur in the United States. An estimated 1 in 92 adults will be diagnosed with oral or pharyngeal cancer in their lifetime.

There are multiple and varied risk factors involved in the development of head and neck cancerous lesions. For example, the use of tobacco and alcohol is strongly related to oral cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, “3 out of 4 people with oral cancer have used tobacco, alcohol or both.” It is said that combining the use of tobacco and alcohol will increase the risk of a malignancy by 15 times.

Viruses have been also implicated in the development of oral and oropharyngeal cancer and, of these, human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 are strongly associated and are thought to cause about half of all oropharyngeal cancer cases. HPV is a common virus, and in most instances the person’s immune system will clear the HPV infection. Only 1% of those infected will display a lack of immune response.

Sun exposure is also a risk factor for developing skin cancers, manifesting itself in the orofacial region as lip cancer. Furthermore, diets that lack vegetables and fruits, personal history of cancer, betel nut chewing, and other unspecific or minor risk factors are researched, known, and cited. At one time a controversy regarding the relationship between mouthwash use and increased risk for developing oral cancer arose, but proved to have no scientific evidence.

Demographic characteristics have changed over the years. Historically, cancer usually affected older people and, with respect to oral cancers, mostly male smokers or heavy drinkers. The newly recognized HPV16 association with oropharyngeal cancer should eventually shed some light on the more recent reports of changes in age, gender, and race of persons with oral cancer.

Radiology can be a valuable tool in the detection and diagnosis of malignant disease, as intraosseous malignancies, in addition to those that start peripherally but later invade bone, can cause detectable changes in the calcified structures of the teeth and bone. Many of the changes to bone brought about by malignancies either tend to be lytic or cause alterations to the normal trabecular pattern. The characteristic irregular and spike patterns of resorption of the roots of teeth are other changes to calcified structures that may originate from a malignancy.

Although malignancies represent a small fraction of both the common and uncommon lesions of the jaws, early detection is of constant and significant concern to practicing dentists. Along with regular oral cancer screenings, clinical surveillance for suspicious lesions, routine intraoral dental imaging, and panoramic radiographs often provide the ability to effectively visualize osseous lesions of malignant disease.

Initial discovery of oral and maxillofacial malignancies may result from complaints of pathognomonic symptoms, discovery of soft-tissue components of lesions during intraoral and extraoral examinations, or, rarely, radiographic findings. Most lesions are discovered late, after invasion of the regional lymph nodes, which may have become enlarged and sometimes painful. At present there is no specific tool or test in widespread use by dentists that could aid in oral and maxillofacial cancer screening and detection, other than meticulous clinical examination of the hard and soft tissues of the orofacial regions in addition to follow-up of suspected lesions with further testing, including appropriate radiographic examinations. The final and definitive diagnosis is generally the histopathology report, supplemented with clinical and radiographic findings.

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research describe one method of clinical examination. The American Cancer Society and American Dental Association recommend that primary care clinicians and dentists initiate periodic examinations of the oral cavity and throat as part of routine cancer-related screenings. The high-risk areas for oral cancer are the lateral borders of the tongue, the floor of the mouth and ventral side of tongue, the soft palate, and the tonsils. These and all of the other visible structures should be carefully examined during an oral cancer screening.

Oral cancer screening is an extremely important and sensitive topic, but despite the attention that cancer receives in both professional and lay publications, most oral cancers go unnoticed in their initial detectable stages. Dentists are trained to search for white or red patches, in addition to ulcers, during clinical examinations. Radiographic signs are also emphasized. This approach should be expanded to include HPV-related malignancies, which typically do not display discolored patches and, therefore, may go undetected for longer periods. Nevertheless, early detection, even if sometimes difficult, is the goal and currently is the main factor that might provide an improved prognosis. These recommended oral cancer screenings take place every 3 years for persons older than 20 and annually for those older than 40 years.

Tables 1–4 show the pertinent details of benign and malignant lesions, and their differentiation from inflammatory lesions.

| Appearance | 2D Radiographs | CBCT/MDCT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Radiopaque | High density (bone) | High-intensity signal (fluid, fat) |

| Contrast agents: enhancement | |||

| Black | Radiolucent | Low density (air, fluid) | Low-intensity signal (cortical bone) |

| Gray | Gray appearance is extremely relative to surroundings; can appear Radiopaque (sinusitis) or Radiolucent (intraosseous tumor) | Soft-tissue density | Isointense to muscle |

| Features | Common to All | Unique to Some |

|---|---|---|

| Location and size | Almost anywhere; invade bone from soft tissues in risk areas; various sizes | Posterior mandible: sarcomas and metastases |

| Shape and borders | Irregular, ill-defined and noncorticated borders, finger-like projections, permeative pattern | Well-defined: some SCCs, IMC |

| Internal structure and density | Radiolucent: destructive, permeative pattern; remnant trabeculae | Radiopaque: osteosarcomas, breast and prostate metastases |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Irregular widening of the periodontal ligament space with floating-teeth appearance, resorption of cortical outlines, invasion of adjacent structures, no periosteal reaction | Root resorption: sarcomas and multiple myeloma Periosteal reaction with sunray/hair-on-end appearance: osteosarcomas and prostate metastases |

| Features | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Almost anywhere (intraosseous or arising in soft tissue or cartilage) | Almost anywhere, depending on tissue of origin |

| Shape | Regular | Irregular |

| Borders | Corticated, well-defined; if inflamed can become poorly defined or punched-out, noncorticated; narrow transition zone | Mostly ill-defined; moth-eaten, permeative/infiltrative; wide transition zone |

| Density | Radiolucent, mixed, or radiopaque | Mostly radiolucent, with remnant trabeculae |

| Size | Varying sizes: from very small to extremely large | Same |

| Internal structure | Various degrees of homogeneity and different trabecular patterns: “honeycomb,” “soap bubble,” “tennis racket,” etc Uni- or multilocular |

Heterogeneous, usually no discernible trabecular pattern Remnant trabeculation |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Thinning and displacement of roots, cortical plates, sinus floor, mandibular canal Rarely interruption/effacement |

Rare displacement, mostly interruption with invasion of adjacent structures/spaces |

| Features | Inflammation | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Invades bone from adjacent structures (maxillary sinuses, teeth, soft tissues) | Same |

| Shape | Irregular | Same |

| Borders | Ill-defined, permeative, rarely corticated; wide transition zone | Same |

| Density | Depending on stage, varies from radiolucent to opaque and also mixed; sequestrum formation | Mostly radiolucent; remnant trabeculation may mimic sequestra |

| Size | Any size | Any size |

| Internal structure | Altered/resorbed trabecular pattern | Same |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Resorptive and/or stimulating new bone formation effects on adjacent cortices/medullar bone Root resorption Interruption/perforation of cortices Periosteal reaction (“onion skin”) |

No effect in surrounding trabecular bone No periosteal reaction (exception osteosarcoma: “sunburst”) Most frequently no root resorption Perforation, pathologic fracture, invasion present |

Introduction

This article highlights the radiographic features of malignant lesions and presents the clinical correlations that may aid in the initial diagnosis of orofacial malignancies.

The word “malignant” comes from the Latin malignare , meaning “to act wickedly” ( mal = “bad”). Cancer appears when a stimulus triggers abnormal changes to the chromosomes within cells. The initial stage that can be detected by histopathologic examination is called dysplasia (abnormality) and there are multiple evolutionary stages known, such as carcinoma in situ, primary neoplasm, and secondary or metastatic neoplasm. Most changes take place at the subcellular level and manifest themselves as uncontrolled multiple cell divisions and persistence of old cells while young cells do not mature and differentiate. The clinically visible aspect is usually a late one, illustrated by the cancerous growth, tumor, or mass. It may be at this point that radiographically evident changes also occur.

In contrast to a benign lesion, a malignant tumor is characterized by uncontrolled growth potential, an aggressive and invasive nature, and the ability to metastasize. If a tumor arises de novo it is called a primary tumor, and if it originates from a distant tumor it is referred to as secondary or metastatic. Metastases share the tissues of the primary tumor, but they occur in a different and, frequently, distant location. Metastases illustrate the spread of cancer cells, usually traveling through the blood or lymph vessels, and can invade and develop in any other anatomic region. Often, the first site of neoplastic invasion is the nearby lymph nodes.

According to the National Cancer Institute, “head and neck cancers, which include cancers of the oral cavity, larynx, pharynx, salivary glands and nose/nasal passages, account for 3% of all malignancies in the US.” Cancers of the oral cavity represent 85% of all head and neck cancers, the eighth most common malignancy in males and 15th most common in females. Estimates for 2015 are far from gratifying. The Oral Cancer Foundation and American Cancer Society estimate in 2015 that 43,000 to 45,000 new cases of oral and oropharyngeal cancers with 8000 to 8650 deaths (approximately 1 per hour) will occur in the United States. An estimated 1 in 92 adults will be diagnosed with oral or pharyngeal cancer in their lifetime.

There are multiple and varied risk factors involved in the development of head and neck cancerous lesions. For example, the use of tobacco and alcohol is strongly related to oral cancer. According to the American Cancer Society, “3 out of 4 people with oral cancer have used tobacco, alcohol or both.” It is said that combining the use of tobacco and alcohol will increase the risk of a malignancy by 15 times.

Viruses have been also implicated in the development of oral and oropharyngeal cancer and, of these, human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18 are strongly associated and are thought to cause about half of all oropharyngeal cancer cases. HPV is a common virus, and in most instances the person’s immune system will clear the HPV infection. Only 1% of those infected will display a lack of immune response.

Sun exposure is also a risk factor for developing skin cancers, manifesting itself in the orofacial region as lip cancer. Furthermore, diets that lack vegetables and fruits, personal history of cancer, betel nut chewing, and other unspecific or minor risk factors are researched, known, and cited. At one time a controversy regarding the relationship between mouthwash use and increased risk for developing oral cancer arose, but proved to have no scientific evidence.

Demographic characteristics have changed over the years. Historically, cancer usually affected older people and, with respect to oral cancers, mostly male smokers or heavy drinkers. The newly recognized HPV16 association with oropharyngeal cancer should eventually shed some light on the more recent reports of changes in age, gender, and race of persons with oral cancer.

Radiology can be a valuable tool in the detection and diagnosis of malignant disease, as intraosseous malignancies, in addition to those that start peripherally but later invade bone, can cause detectable changes in the calcified structures of the teeth and bone. Many of the changes to bone brought about by malignancies either tend to be lytic or cause alterations to the normal trabecular pattern. The characteristic irregular and spike patterns of resorption of the roots of teeth are other changes to calcified structures that may originate from a malignancy.

Although malignancies represent a small fraction of both the common and uncommon lesions of the jaws, early detection is of constant and significant concern to practicing dentists. Along with regular oral cancer screenings, clinical surveillance for suspicious lesions, routine intraoral dental imaging, and panoramic radiographs often provide the ability to effectively visualize osseous lesions of malignant disease.

Initial discovery of oral and maxillofacial malignancies may result from complaints of pathognomonic symptoms, discovery of soft-tissue components of lesions during intraoral and extraoral examinations, or, rarely, radiographic findings. Most lesions are discovered late, after invasion of the regional lymph nodes, which may have become enlarged and sometimes painful. At present there is no specific tool or test in widespread use by dentists that could aid in oral and maxillofacial cancer screening and detection, other than meticulous clinical examination of the hard and soft tissues of the orofacial regions in addition to follow-up of suspected lesions with further testing, including appropriate radiographic examinations. The final and definitive diagnosis is generally the histopathology report, supplemented with clinical and radiographic findings.

The National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research describe one method of clinical examination. The American Cancer Society and American Dental Association recommend that primary care clinicians and dentists initiate periodic examinations of the oral cavity and throat as part of routine cancer-related screenings. The high-risk areas for oral cancer are the lateral borders of the tongue, the floor of the mouth and ventral side of tongue, the soft palate, and the tonsils. These and all of the other visible structures should be carefully examined during an oral cancer screening.

Oral cancer screening is an extremely important and sensitive topic, but despite the attention that cancer receives in both professional and lay publications, most oral cancers go unnoticed in their initial detectable stages. Dentists are trained to search for white or red patches, in addition to ulcers, during clinical examinations. Radiographic signs are also emphasized. This approach should be expanded to include HPV-related malignancies, which typically do not display discolored patches and, therefore, may go undetected for longer periods. Nevertheless, early detection, even if sometimes difficult, is the goal and currently is the main factor that might provide an improved prognosis. These recommended oral cancer screenings take place every 3 years for persons older than 20 and annually for those older than 40 years.

Tables 1–4 show the pertinent details of benign and malignant lesions, and their differentiation from inflammatory lesions.

| Appearance | 2D Radiographs | CBCT/MDCT | MRI |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | Radiopaque | High density (bone) | High-intensity signal (fluid, fat) |

| Contrast agents: enhancement | |||

| Black | Radiolucent | Low density (air, fluid) | Low-intensity signal (cortical bone) |

| Gray | Gray appearance is extremely relative to surroundings; can appear Radiopaque (sinusitis) or Radiolucent (intraosseous tumor) | Soft-tissue density | Isointense to muscle |

| Features | Common to All | Unique to Some |

|---|---|---|

| Location and size | Almost anywhere; invade bone from soft tissues in risk areas; various sizes | Posterior mandible: sarcomas and metastases |

| Shape and borders | Irregular, ill-defined and noncorticated borders, finger-like projections, permeative pattern | Well-defined: some SCCs, IMC |

| Internal structure and density | Radiolucent: destructive, permeative pattern; remnant trabeculae | Radiopaque: osteosarcomas, breast and prostate metastases |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Irregular widening of the periodontal ligament space with floating-teeth appearance, resorption of cortical outlines, invasion of adjacent structures, no periosteal reaction | Root resorption: sarcomas and multiple myeloma Periosteal reaction with sunray/hair-on-end appearance: osteosarcomas and prostate metastases |

| Features | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Almost anywhere (intraosseous or arising in soft tissue or cartilage) | Almost anywhere, depending on tissue of origin |

| Shape | Regular | Irregular |

| Borders | Corticated, well-defined; if inflamed can become poorly defined or punched-out, noncorticated; narrow transition zone | Mostly ill-defined; moth-eaten, permeative/infiltrative; wide transition zone |

| Density | Radiolucent, mixed, or radiopaque | Mostly radiolucent, with remnant trabeculae |

| Size | Varying sizes: from very small to extremely large | Same |

| Internal structure | Various degrees of homogeneity and different trabecular patterns: “honeycomb,” “soap bubble,” “tennis racket,” etc Uni- or multilocular |

Heterogeneous, usually no discernible trabecular pattern Remnant trabeculation |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Thinning and displacement of roots, cortical plates, sinus floor, mandibular canal Rarely interruption/effacement |

Rare displacement, mostly interruption with invasion of adjacent structures/spaces |

| Features | Inflammation | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|

| Location | Invades bone from adjacent structures (maxillary sinuses, teeth, soft tissues) | Same |

| Shape | Irregular | Same |

| Borders | Ill-defined, permeative, rarely corticated; wide transition zone | Same |

| Density | Depending on stage, varies from radiolucent to opaque and also mixed; sequestrum formation | Mostly radiolucent; remnant trabeculation may mimic sequestra |

| Size | Any size | Any size |

| Internal structure | Altered/resorbed trabecular pattern | Same |

| Effects on surrounding structures | Resorptive and/or stimulating new bone formation effects on adjacent cortices/medullar bone Root resorption Interruption/perforation of cortices Periosteal reaction (“onion skin”) |

No effect in surrounding trabecular bone No periosteal reaction (exception osteosarcoma: “sunburst”) Most frequently no root resorption Perforation, pathologic fracture, invasion present |

Classification

Once there is an initial diagnosis, advanced functional and anatomic imaging allows the cancer to be classified according to TNM staging. T is used to describe the primary tumor (size, aggressiveness), N addresses involved nearby lymph nodes, and M describes distant metastases. It is internationally accepted and used, but of importance only when solid tumors are considered or assessed. It is of no use for staging a diffuse malignancy such as leukemia.

There are other classifications, depending on:

-

Tissue of Origin

- •

Carcinomas: epithelial origin

- •

Sarcomas, mesenchymal

- •

Hematopoietic malignancies: blood and lymph

- •

Metastases

-

Location of Head and Neck Cancers

- •

Oral

- •

Lips

- •

Nasal and nasopharyngeal

- •

Paranasal sinuses

- •

Oropharyngeal

- •

Larynx, thyroid, middle ear, salivary glands

-

Point of Origin

- •

Intraosseous/bony

- •

Soft tissue

- 1.

Carcinomas are malignant tumors of epithelial origin that can arise in either soft tissue or bone.

- a.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) arises in the epithelium of the mucous membranes and skin. It is the second most common cancer of the skin after basal cell carcinoma, and is usually found in areas exposed to sunlight. It seems to affect males more than females (2:1) and more so in the sixth and seventh decades.

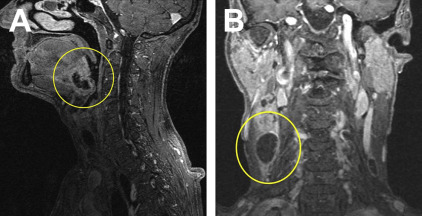

SCC is also the most common head and neck malignancy and best portrays the term “oral cancer.” Almost 90% of all head and neck cancers are SCCs. It should be noted that 25% of oral malignancies are HPV-related and may not provide the typical presentation. SCC is also the most common malignancy of the oral cavity. When it occurs in the oral cavity, it most frequently involves the keratinized mucosa of the posterior mandible. SCC lesions can be easily confused with a benign growth when they are represented by a nontender soft-tissue mass or a nonhealing ulcer that eventually will cause resorption of the underlying bone (see Figs. 3–5 ). In addition to the mucosa, SCC can originate in other soft tissues, including the salivary glands, tongue ( Fig. 1 ), floor of the mouth, and tonsillar area (Waldeyer ring).

- a.