17 Cystic Salivary Gland Tumors Including Cystic Neoplasms

Clinical Classification of Cysts

Benign Lymphoepithelial Cysts and Lesions

Polycystic (Dysgenetic) Disease of the Salivary Gland

Cystic Salivary Gland Neoplasms

Introduction

The diagnosis and management of cystic lesions in the salivary glands has been discussed extensively in the pathology literature. The controversy has largely concentrated on the pathogenesis and classification of salivary cysts, most frequently involving the parotid gland, and this in turn is because experts disagree about the embryological origin of the cysts and the varied components of the morphological features of the cyst wall.

These reports and discussions, while important, have confused clinicians. In addition, the term “parotid cyst” needs to be distinguished from a “cystic parotid,” as the latter includes conditions other than pure cysts. To clinicians, therefore, it might be more useful if cytologists could be more informative about the likely implications of a “salivary cystic aspirate.” Ultimately, the major problem for the surgeon in dealing with parotid cysts is the possibility of missing an associated neoplasm or cysts that are likely to have accompanying congenital abnormalities.

The aims of this chapter are to review the differential diagnosis of salivary swellings from which fluid has been or could be aspirated and to suggest practical guidance on further management for clinicians. Cystic lesions as a group comprise about 5% of all salivary gland tumors, but if neoplasms are excluded, this number is reduced considerably.1 Their importance lies in the fact that the majority are unilateral, and almost 50% simulate benign salivary neoplasms and require surgical removal and histopathological examination. Bilateral or multiglandular salivary involvement is occasionally seen, and this may suggest systemic disease processes such as Sjögren syndrome, cystic fibrosis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Definition

The word “cyst” is derived from the Greek word meaning “bladder.” The pathological term “cyst” means a swelling consisting of a collection of fluid which is lined with epithelium or endothelium.

True and False Cysts

True and False Cysts

True cysts are usually lined with epithelium. If infection supervenes, the lining may be composed of granulation tissue. The fluid is usually serous or mucoid and varies from brown staining, due to altered blood, to almost colorless.

True cyst: a collection of fluid lined with epithelium

True cyst: a collection of fluid lined with epithelium

False cyst: a collection of fluid without an epithelial wall

False cyst: a collection of fluid without an epithelial wall

Clinical Classification of Cysts

Cysts involving the salivary glands can be classified as congenital, acquired, or parasitic (Table 17.1).

Congenital Cysts

Congenital Cysts

Sequestration dermoid is due to dermal cells being buried along the lines of closure of embryonic clefts and sinuses by skin fusion. The cyst is therefore lined with epidermis and contains pastelike, desquamated material. Branchial cleft cysts occur in the parotid region.

Acquired Cysts

Acquired Cysts

Retention cysts are due to the accumulated secretions of a gland following obstruction of the duct. These are commonly found in the major and minor salivary glands. Duct ectasia may be part of a chronic inflammatory process (sialadenitis) or metabolic process (sialadenosis). Nonneoplastic cysts have to be distinguished from cystic changes in the ducts that occur in certain forms of chronic sialadenitis, such as chronic sialectatic parotitis in Sjögren syndrome and HIV. In addition, degenerative cysts associated with tumors (pleomorphic adenoma, adenolymphoma, Warthin tumor) have to be distinguished from tumors that may have cystic pathological processes (cystadenoma, mucoepidermoid tumor, acinic cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma).

|

Congenital/developmental |

|

Polycystic disease of the salivary gland |

|

Salivary duct cysts |

|

First branchial cleft anomalies |

|

? Second branchial cleft anomalies |

|

Nonneoplastic—obstructive |

|

Mucous retention cyst |

|

Salivary duct cysts |

|

Mucoceles |

|

Extravasation—mucus granulomas |

|

Ranula |

|

Retention |

|

Inflammatory |

|

Benign lymphoepithelial cysts (BLECs) |

|

Benign lymphoepithelial lesions (BLELs)

|

|

Benign lymphoepithelial cysts—AIDS–related |

|

Benign neoplasms |

|

Salivary

– Cystadenoma – Myoepithelioma – Cystic pleomorphic adenoma |

|

Neurogenic

|

|

Malignant neoplasms |

|

Salivary

– Acinic cell adenocarcinoma – Cystadenocarcinoma |

|

Lymphoma (MALT lymphoma) |

|

Other lesions |

|

Benign lesions

|

|

Metastatic neoplasms

|

AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HPV, human papillomavirus; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

Parasitic Cysts

Parasitic Cysts

Hydatid disease of the Taenia echinococcus has been reported to affect the parotid gland.

Clinical Features

The majority of cystic salivary gland lesions present as a painless mass in the major salivary glands. These swellings may be small or large, raising concerns that the swelling may be a “tumor.” Occasionally, a patient may present with an acutely swollen and inflamed major salivary gland, and the residual nodule following treatment with aspiration and antibiotics may lead to diagnosis of a salivary cystic lesion. Cystic lesions present as raised submucosal swellings when located in the mouth.

It should be noted that an acute presentation of a major salivary infection or abscess may be the first presentation of a salivary gland cyst.

It should be noted that an acute presentation of a major salivary infection or abscess may be the first presentation of a salivary gland cyst.

Diagnostic Work-Up

Imaging

Imaging

In most clinics, the methods of investigation include imaging studies such as ultrasonography with or without fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and computed tomography with or without FNAC. The clinical diagnosis is frequently a mass that is considered to be solid, but ultrasound evaluation may then reveal a cyst or a mixed solid-cystic lesion. In such a scenario, the fluid should be aspirated and sent for cytology, which may reveal the nature and diagnosis of the swelling. Most cystic lesions present in the lateral lobe, but the same clinical acumen and diagnostic sequences are needed for parotid gland cysts presenting in the deep lobe or parapharyngeal space. If focal nodularity is identified in the cyst wall on imaging, clinicians should be alert to the possibility of neoplasia and an excision biopsy should be recommended, but in the majority of other cystic lesions the cyst walls are smooth. The associated presence of diffuse cervical adenopathy would support a possible diagnosis of HIV infection. While imaging may be helpful in demarcating the cystic lesion as single or multiple, the precise diagnosis is therefore still with the pathologist.2

Aspiration Cytology

Aspiration Cytology

Imaging of solid and cystic salivary swellings is discussed in Chapters 6 and 7. The aspirated fluid may also be a guide to the possible diagnosis.

When FNAC is being used in cystic lesions, it is important to puncture the liquid content and carry out a second puncture to aspirate material from the wall of the cysts. Ultrasound guidance is very helpful, particularly in the second approach. Analyzing both the content and the wall of the cyst improves the likelihood of receiving a significant result from the cytologist.

When FNAC is being used in cystic lesions, it is important to puncture the liquid content and carry out a second puncture to aspirate material from the wall of the cysts. Ultrasound guidance is very helpful, particularly in the second approach. Analyzing both the content and the wall of the cyst improves the likelihood of receiving a significant result from the cytologist.

A systematic approach to the diagnosis of cystic lesions with FNAC can result in a correct diagnosis in 70%–80% of cases.3,4 One should first determine the predominant fluid—mucoid (mucoepidermoid carcinoma, mucous cyst, cystic pleomorphic adenoma, cystadenocarcinoma) or watery and proteinaceous (benign lymphoepithelial cyst, Warthin tumor, cystadenocarcinoma, polycystic disease of the parotid gland). Subsequently, one should evaluate the epithelial components (lymphocytes, histiocytes, epithelial cells, oncocytic change) and the cell clusters. If there is any intramural deformity or irregularity or tissue aggregation, a needle biopsy of that specific area must be performed with imaging guidance, and this may improve the accuracy of the pathological examination.

Errors in Diagnosis

Errors in Diagnosis

Errors may occur when a nest of atypical metaplastic cells from a Warthin tumor is misinterpreted as representing a squamous cell carcinoma, for example. Another concern is that cyst fluid often dilutes the number of cells available for diagnosis. One of the most error-prone and potentially most clinically significant FNAC diagnoses involves mucoepidermoid carcinoma. The FNAC differential diagnosis of mucoepidermoid carcinoma includes: mucous retention cyst, Warthin tumor, branchial cleft cyst, benign lymphoepithelial lesion, chronic obstructive sialadenitis, and necrotizing sialoadenitis. The fluids obtained from Warthin tumors, mucoepidermoid carcinomas, and nonneoplastic cysts may be very similar.5

Benign Salivary Cysts

Benign cysts account for 2%–5% of parotid gland lesions.6 They are rare in the other major glands, but have been reported in the submandibular gland. Benign cysts (sialo-cysts) of the parotid gland can be classified into three types: lymphoepithelial cysts, salivary duct cysts, and dysgenetic cysts.7

Benign Lymphoepithelial Cysts and Lesions

Benign Lymphoepithelial Cysts and Lesions

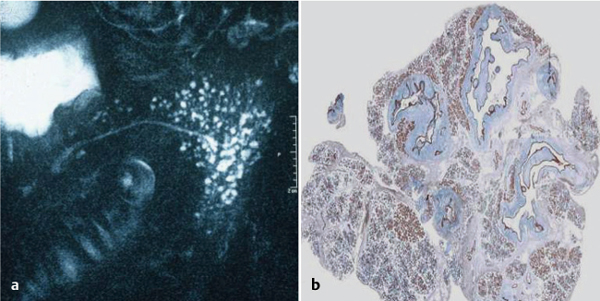

Definition

The benign lymphoepithelial cysts (BLECs) or benign cystic lymph nodes described by Bernier and Bhaskar8 can occur in the salivary glands, cervical lymph nodes, oral cavity (floor of the mouth), tonsil, thyroid gland, pancreas, and juxtabronchially. The term was introduced to replace “branchial cleft cyst.” The authors emphasized that this lesion was not an embryonic remnant, but instead arose from parotid gland inclusions inside lymph nodes.9 More recent studies have suggested that the lymphoid stroma is induced along with cystic dilation of ducts in sialadenitis (Fig. 17.1), not induced either by Epstein–Barr virus or HIV infection, and that the formation of lymphoepithelial cysts concludes with demarcation (which should involve some form of granulation tissue reaction) from the parotid parenchyma and does not arise from intraparotid lymph nodes.10 More recent pathological studies have considered that BLECs are the same as the benign lymphoepithelial lesions (BLELs) described in Sjögren syndrome.11,12

Clinical Features

BLECs are usually well-circumscribed symptomatic masses located in the superficial portion of the gland; one-third of the cases have a multilocular structure. They range in size from 0.5 to 6.0 cm and average about 2.5 cm in diameter. The majority of lesions are unilateral, although bilateral lesions have been reported, and most have been diagnosed in patients in the fifth decade of life. However, the cysts can also occur bilaterally, in patients who do not have Sjögren syndrome or any other identifiable disease.

Pathological Description

In addition to an integral lymphoid component, the cysts have a lining of squamous, cuboidal, or columnar cells, or any combination of cells. The contents of the cysts vary from watery fluid to a thick, opaque, and gelatinous material. In other instances, so-called branchial cleft cysts are encountered in which lymphoid components have all the features of a lymph node (i.e., capsular sinus, medullary sinuses, and germinal centers) and no skin appendages are present. This has led some to suggest that these cysts do not arise from branchial cleft abnormalities but rather from benign parotid inclusions, which are well documented in intraparotid and periparotid lymph nodes. Opponents of this view suggest that the presence of ciliated epithelium in the lining cannot support the lymph-node theory. These cysts are frequently misdiagnosed clinically as benign tumors. More recent studies do not support the involvement of myoepithelial cells in duct lesions in patients with Sjögren disease.13 The immunological reaction to pankeratin can be very helpful for a thorough pattern analysis of different lymphoepithelial lesions. The relative frequency of the lesions in different salivary glands can also be diagnostically helpful.14

Treatment

Surgical excision provides an accurate diagnosis and a complete cure. Although these lesions are clearly lymphoepithelial in their composition, they have not been found to have any relationship to the lymphoepithelial lesions seen in chronic sialadenitis or any immune disorders.6

Fig. 17.1 a, b A chronic sialectatic parotid gland with keratinizing cysts. (Pathological images courtesy of Dr. Stephan Ihrler, Munich, Germany.)

Salivary Duct Cysts

Salivary Duct Cysts

Salivary duct cysts may be acquired or congenital. True cysts are distinguished from pseudocysts by the presence of an epithelial lining. The majority of true cysts involving the major salivary glands arise on the parotid gland. However, the majority of salivary duct cysts are acquired, and most of these are probably secondary to obstruction. Some authors therefore prefer the term “retention cyst,” while others use the term “simple cyst.” The differential diagnosis of salivary duct cysts mainly involves cystadenocarcinomas and well-differentiated cystic mucoepidermoid carcinomas.15

Polycystic (Dysgenetic) Disease of the Salivary Gland

Polycystic (Dysgenetic) Disease of the Salivary Gland

This is the least common of the benign cystic lesions of the parotid gland and is considered to be a developmental malformation of the ductal system; it was first described in 1996.16 Fewer than 50 cases have been recorded, and the condition has been described in the major and minor salivary glands. It typically presents as a recurrent painless, diffuse swelling of the involved gland or glands, but cystic dilation of the salivary ductal system can develop. There has been a recent case report of atypical epithelial hyperplasia and low-grade in situ mucoepidermoid transformation.17

Mucoceles

Mucoceles are spherical, nontender, circumscribed mucosal swellings of varying sizes that contain mucus. Two types are distinguished: extravasation mucoceles and retention mucocles.18

Extravasation Mucoceles

Extravasation Mucoceles

Etiology. The cause of the mucous extravasation cyst is considered to be mechanical trauma in minor excretory ducts, leading to severance of the duct and resultant spillage of mucus into the connective-tissue stroma. The mucus pool is localized or walled off by condensation of connective granulation tissue.

More than 80% of mucoceles are of this type, and the lesions have also been termed “mucous granulomas.” Macroscopically, they appear as a spherical cyst with a diameter of 1.0–1.5 cm which bulges on the surface and is mobile over the surrounding tissue. Almost 80% are located in the lower lip, while a further 15% are seen in the cheek or floor of the mouth, and the remaining 5% are found in the palate, tongue, and upper lip. The peak incidence is in the second decade of life, and 60% occur in men.

Retention Mucoceles

Retention Mucoceles

These are considerably less common than extravasation mucoceles, but they are more common in older patients, with a peak incidence in the eighth decade. They are caused by blockage of mucus in a ductal system. Retention mucoceles are distributed evenly among the minor salivary glands (20% each in the lower lip and cheek and 15% each in the upper lip, palate, floor of the mouth, and tongue). Partial obstruction of the duct due to microliths, inspissated secretions, or bends in the ductal system plays a major role in the pathogenesis of retention mucoceles. Excision biopsy is recommended to exclude underlying neoplasms such as cystadenoma, well-differentiated mucoepidermoid carcinoma, and the papillary cystic type of acinic cell carcinoma.13

HIV–Associated Salivary Cysts

Signs and symptoms of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) are being increasingly easily recognized in the field of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery.19

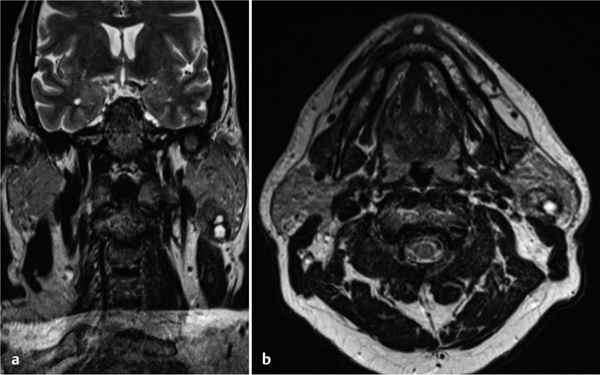

Clinical Features

Cervical lymphadenopathy is associated with lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland in more than 90% of cases (Fig. 17.2). It is usually bilateral (80%), multiple (in up to 90%), painless, and involves the lateral lobe; it rarely involves the submandibular glands.20 These are lymphoepithelial cysts and are known as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related parotid cysts (ARPCs). A major difference between ARPCs and BLEL cysts is that ARPCs originate in periparotid and intraparotid lymph nodes (although some spillage into the surrounding gland may occur), whereas BLELs originate inside the gland and cause acinar atrophy. It may occasionally be difficult to differentiate HIV–associated parotid cysts from Warthin tumor.21

Diagnostic Work-Up

Computed tomography (CT) usually demonstrates multilocular cysts. No cases of benign lymphoepithelial cyst have been known to degenerate into malignancy. Needle biopsy (FNAC) should be performed for cytology, which reveals a triad of a heterogeneous lymphoid population (lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells), scattered foamy macrophages, and anucleated squamous cells.

Fig. 17.2 a, b An HIV–associated lymphoepithelial cyst.

Treatment

Surgical excision was performed in the past, but nonsurgical management is now recommended due to the risk to patients and the fact that surgical management has no effect on the underlying disease. The options for HIV–associated BLEC include observation, repeated aspiration, antiretroviral medication, sclerosing therapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. Sodium morrhuate injection therapy after aspiration has been found to be safe and should be offered to patients who are concerned about the cosmetic effect of the swelling. This is a minimally invasive and efficacious technique for treating benign lymphoepithelial cysts in the parotid gland in HIV–positive patients.22

A major point of distinction between ARPCs and BLEL cysts is that ARPCs originate in periparotid and intraparotid lymph nodes, whereas BLELs originate inside the gland and cause acinar atrophy.

A major point of distinction between ARPCs and BLEL cysts is that ARPCs originate in periparotid and intraparotid lymph nodes, whereas BLELs originate inside the gland and cause acinar atrophy.

Careful pathological analysis is necessary in order to distinguish between lymphoepithelial cysts and cystic BLELs.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

Associated with Sjögren syndrome

Associated with Sjögren syndrome Not related to Sjögren syndrome

Not related to Sjögren syndrome Warthin tumor (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum)

Warthin tumor (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum) Schwannomas (plexiform neurofibroma)

Schwannomas (plexiform neurofibroma) Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, usually intermediate/low-grade

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, usually intermediate/low-grade Dermoid cyst

Dermoid cyst Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin

Squamous cell carcinoma of the skin Cystic metastatic lymph-node metastasis—HPV–associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma

Cystic metastatic lymph-node metastasis—HPV–associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma Papillary thyroid cancer

Papillary thyroid cancer