The craniofacial team, p. 295). Craniofacial units usually provide care to both paediatric and adult patients.

Classification

Numerous classifications exist with little agreement as to which offers the best approach. Each has advantages and disadvantages (see ![]() Further reading, p. 296 for more information).

Further reading, p. 296 for more information).

For the purposes of simplicity the following classification will be utilized:

• Craniosynostosis: group of conditions characterized by the premature closure of the skull vault sutures.

• Craniofacial clefting disorders: characterized by a failure of the developing branchial arches (or other structures) to fuse or possibly the breakdown of previously-fused structures.

• Craniofacial tumours: only specific to craniofacial surgery because of their location and the necessity to utilize craniofacial techniques for their surgical management.

• Head and neck vascular anomalies.

Craniosynostosis

Craniosynostosis is the premature fusion of one or more of the skull vault sutures. Termed ‘simple’ synostosis if single suture involved and ‘complex’ if multiple sutures are involved. Most complex cases are syndromic whereas most single suture synostoses are not. However, there are rare single-suture synostoses associated with syndromes, e.g. unilateral coronal synostosis associated with FGFR3 gene mutations (Muenke syndrome).

• Premature fusion of a suture can result in:

• restricted growth at right angles to the affected suture;

• degree of compensatory overgrowth (or bossing) in other areas of the skull vault;

• raised intracranial pressure.

• In multiple suture or syndromic craniosynostoses head shape is determined by the number and site of the involved sutures. Can result in severe restriction of skull vault growth along with:

• raised intracranial pressure;

• exophthalmos;

• optic dislocation (globes herniate anterior to eyelids);

• restricted mid-face growth (upper airway and feeding difficulties).

The severity of functional problems varies from case to case, as does age of onset. Thus babies born with such conditions need early referral and close monitoring so that intervention is timely to minimize long-term effects. With the syndromic craniosynostoses other related abnormalities (e.g. cardiac, skeletal, renal) will vary from syndrome to syndrome.

Craniosynostosis can also be the by-product of a variety of other conditions, so-called ‘secondary’ synostosis. There is a higher incidence of raised intracranial pressure in this group which therefore require close monitoring.

Single-suture synostosis

Presentation

• Appears soon after birth or in early infancy, after the effects of birth canal moulding should have resolved.

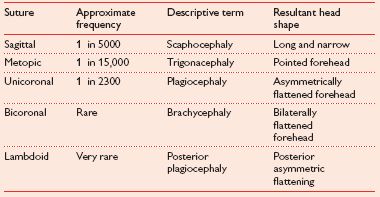

• Most obvious feature is an abnormally shaped head, which is determined by affected suture (Table 6.1).

Table 6.1 Suture and resulting head shape

Signs

• Examine for raised intracranial pressure:

• palpate fontanelles;

• fundoscopy.

• Affected suture often ridged.

Investigations

Plain radiology

• Not particularly helpful since images are commonly poor quality and difficult to interpret.

• In the case of a unilateral coronal synostosis the shape of the orbit (‘harlequin eye’) may be helpful.

CT, MRI, or USS

• Of more use.

• In some units CT reserved for complex cases and those who decline surgery.

Management

• Refer all patients to a craniofacial team for comprehensive care (allows full diagnostic assessment and formulation of management plan).

• Indications for treatment:

• to improve appearance;

• small percentage of patients have associated raised ICP.

• Some evidence that surgical treatment results in better intellectual outcomes (but not universally accepted).

• Intervention involves:

• removal of affected suture (‘suturectomy’);

• remodelling of skull shape.

• Exact procedure and degree of remodelling will vary from case to case and craniofacial unit to unit.

• Cases involving the forehead: the key procedure is a fronto-orbital advancement:

• recontoured skull components are plated into position with resorbable fixation;

• in selected cases distraction osteogenesis is used.

• In general, surgery at about the age of 1 year in uncomplicated cases is the norm.

• For sagittal synostosis surgery can be performed at 6 months (some centres advocate earlier surgery).

• For straightforward single-suture cases follow-up after surgery is usually when the child starts school with the anticipation of no further intervention being necessary.

• In unilateral coronal synostosis there may be residual facial asymmetry that should be managed conventionally as for other facial asymmetries. Longer-term follow-up may be indicated.

Syndromic synostosis

There are numerous syndromes associated with synostosis. The most common are discussed, although management principles are the same for all.

Crouzon’s syndrome

• Autosomal dominant condition associated with the FGFR2 gene mutation.

• Commonly presents with a bicoronal synostosis but other sutures may also be involved.

• Extent of mid-face hypoplasia and degree of exorbitism variable.

• Incidence of raised ICP much higher than non-syndromic bicoronal synostosis.

• Presenting problems vary as does the time of presentation but commonly the diagnosis is suspected at birth or soon after.

• There are often subtle skeletal abnormalities affecting the limbs but these are rarely obvious or symptomatic.

Apert’s syndrome

• Also an autosomal dominant condition caused by a mutation of the FGFR2 gene.

• Craniosynostosis often affects the bicoronal as well as other sutures, resulting in a tall skull flattened anteriorly and occipitally.

• Variable hypertelorism with downward slanting of palpebral fissures.

• Variable exorbitisim.

• Shallow orbits and shortened skull base.

• Most obvious extra-cranial feature is a variable degree of hand and foot abnormalities with complex syndactyly. It is this feature that usually makes clinical diagnosis straightforward.

• As the child develops, the face takes on the shape of an inverted triangle:

• hyperteloric eyes form the wide base;

• hypoplastic maxilla often with crossed central incisors form the apex.

• Cleft palate is a common (17–43%) association and in those without a cleft the palate is narrow and high-arched.

• Intellectual impairment is more common than in Crouzon’s syndrome.

Saethre–Chotzen syndrome

Presentation much more variable.

• Autosomal dominant.

• Late presentation (adulthood) common.

• Asymmetric complex bicoronal synostosis that may be mild (accounting for late presentations).

• Ptosis.

• Tear duct abnormalities.

• Low hairline.

• Parrot-beaked nasal shape.

Pfeiffer syndrome

• Autosomal dominant.

• Variable presentation of complex synostosis, the most severe being the clover-leaf skull (Kleeblattschädel) deformity.

• The digits (particularly thumbs and big toes) are broad and short.

Principles of management

Diagnosis

• Prenatal diagnosis becoming more commonplace.

• Diagnosis in early postnatal period still the norm.

• Clinical assessment confirmed with genetic testing.

Initial management

• Aimed at assessing and minimizing effects of the condition on vital functions:

• breathing;

• eating;

• scleral cover;

• presence of raised ICP.

• In some cases urgent tracheostomy and eyelid surgery is necessary.

• Consider feeding via a NGT.

• Systematic approach to investigate for additional abnormalities.

• Significant amount of time needs to be devoted to counselling parents and other family members about the condition and its implications.

Early management

• In general, approach to the cranial abnormalities similar to single-suture cases.

• Surgery aimed at increasing cranial vault volume and improving the overall shape, thus dealing with the potential raised ICP and aesthetic concerns.

• Number of different designs of procedure for each type of abnormality and different units utilize different approaches.

• Surgical principle—re-assembled skull bones held in position with resorbable fixation.

• In some units there is a move away from initial fronto-orbital advancement. Instead a posterior skull vault expansion is carried out delaying any further aesthetic procedures to the anterior of the skull until the craniofacial complex is further developed.

• For some cases, particularly those with significant symptomatic exorbitism, a monoblock procedure can be carried out:

• fronto-orbital bar left attached to the mid-face;

• whole unit is advanced, bringing the maxilla, orbital rims, and forehead forward.

• Distraction osteogenesis has been used as an alternative to conventional osteotomies and plate fixation.

• In terms of timing the initial cranial vault expansion, a balance between a number of factors needs to be reached:

• if the infant is developing signs of raised ICP then surgery should not be delayed;

• in elective cases the general state of development, co-morbidity, and size should be taken into account;

• in most craniofacial units surgery is proposed from 6–15 months of age with the tendency for earlier surgery for sagittal synostosis.

Infancy to adolescence

Monitoring for re-synostosis.

Treatment of associated problems

• Proactive management of vision and hearing.

• Genetic assessment and counselling of parents should they be considering having more children.

• Consideration of further mid-face surgery and/or hypertelorism correction.

• Orthodontic input.

• Management of obstructive sleep apnoea. This can occur as a result of mid-face retrusion and, therefore, mid-face advancement may be helpful. Investigation with formal sleep studies and appropriate imaging will help identify and quantify the problem, as well as aid in localizing the level of airway obstruction.

Adolescence to the completion of growth

• Emphasis should be on final aspects of surgery to mid-face and skull.

• Regular monitoring for the functional manifestations of raised ICP (clinical features as well as papilloedema and formal optic field assessment).

• Developmental and psychological issues.

• Patients should be assessed and managed as for other facial abnormalities:

• conventional orthognathic surgery;

• distraction osteogenesis;

• other aesthetic surgery techniques, e.g. rhinoplasty, forehead recontouring.

Torticollis and positional skull deformity

Both of these conditions deserve mention because they are often mistaken for craniosynostosis, particularly a unilateral coronal synostosis. In addition the management of deformational skull deformity is controversial with a variety of experts utilizing helmet moulding to improve the head shape.

Torticollis

•

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses