Initial management of ocular injuries, p. 16.)

Priority setting in polytrauma

Multidisciplinary considerations

Life- or sight-threatening facial injuries should be treated immediately. Facial lacerations and unstable mandibular fractures should be treated within 24h. Most other bony facial injury can be treated on a delayed basis. The delay involved is dependent upon the amount of facial oedema present. Mid-face and orbital injuries should either be treated before the onset of facial oedema or after facial oedema has settled. The decision of definitive timing to treat injuries is also affected by other injuries, and the need to treat major chest, abdominal, pelvic, and limb trauma.

Imaging

Polytrauma patients are often immobilized or supine due to potential spinal injuries.

Plain film radiographs for facial injuries include:

• Occipito-mental (OM) views.

• Orthopantomogram (OPG).

• Postero-anterior (PA) mandible.

Unfortunately, all three of these views require the patient to be upright. In the multiple-injury patient this is not possible. If the patient cannot stand and has clinical indicators that suggest significant bony facial injury, a fine-cut (0.5mm) CT scan of the area should be considered. Every effort should be made to incorporate facial imaging into trauma protocols. If a patient is having a CT of their head and cervical spine and they have facial injuries, they should have simultaneous imaging of the face.

‘How to do’ emergency procedures

Airway management

Except in the management of battlefield trauma, where control of catastrophic haemorrhage takes priority, the airway always takes first priority and should be managed in association with protection of the cervical spine. Airway management can be summarized as follows:

• Clear debris from the airway.

• Posture. In the absence of associated spinal injuries it is appropriate to sit the patient up. Patients with grossly displaced mandibular injuries, such as those from gunshot wounds, should be allowed to sit leaning forward so that the tongue and any debris from the oral cavity is allowed to fall away from the airway.

• Neck extension and jaw thrust also helps to clear the airway, although neck extension is not permitted in the case of suspected injuries to the cervical spine.

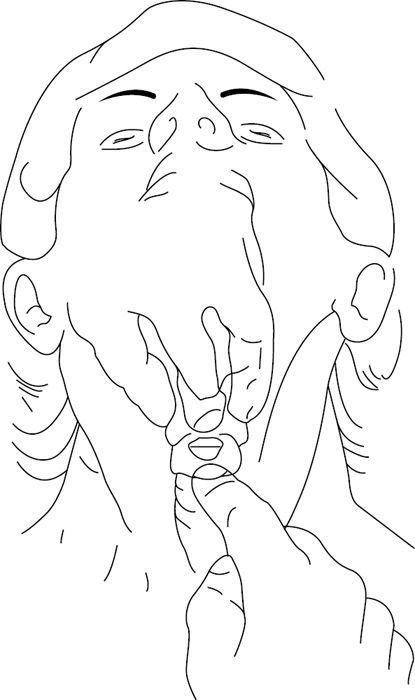

• A Guedel airway can be used to help maintain the airway temporarily in a patient with reduced consciousness (Fig. 1.1). The majority of these patients will need a definitive airway, i.e. one in which there is a tracheal cuff to prevent debris escaping into the lungs. The best example of this is the endotracheal tube (ETT, Fig. 1.2).

Vomiting in the immobilized patient

Patients immobilized on a spinal board who vomit are in grave danger of aspiration as they cannot sit up to clear their airway. If such a patient is about to vomit they should be immediately turned on their side on the spinal board.

Surgical airways

An emergency surgical airway can be achieved in one of two ways.

Needle cricothyroidotomy

This provides a temporary surgical airway. In essence, it supplies the patient with oxygen, but without a definitive surgical airway there is an inevitable build-up of CO2,which limits the usefulness of this technique.

Technique

• Make sure there is an oxygen supply and tubing available.

• Place patient in a supine position.

• Assemble a 12G or 14G needle with a 5mL syringe.

• Surgically prepare the neck using antiseptic swabs.

• Identify the cricothyroid membrane, between the cricoid cartilage and the thyroid cartilage. Stabilize the trachea with the thumb and forefinger of one hand to prevent lateral movement of the trachea during performance of the procedure.

• Puncture the skin in the midline with the needle attached to the syringe, directly over the cricothyroid membrane. A small incision with a No. 11 blade may facilitate passage of the needle through the skin.

Fig. 1.1 Initial airway management of multiple facial injuries with Guedel airway.

Fig. 1.2 Initial airway management of multiple facial injuries with the ETT.

• Direct the needle at a 45° angle inferiorly, while applying negative pressure to the syringe, and carefully insert the needle through the lower half of the cricothyroid membrane. Aspiration of air signifies entry into the tracheal lumen.

• Remove the syringe and attach the oxygen tubing over the needle hub. Intermittent ventilation can be achieved by occluding the open hole cut into the oxygen tubing with your thumb for 1s and releasing it for 4s.

Cricothyroidotomy

Surgical cricothyroidotomy provides a definitive surgical airway. It is a procedure that can be performed extremely rapidly and, in an emergency, any rigid tube with a hollow lumen can used. Specially designed cricothyroidotomy tubes are available.

Technique

• Place the patient in a supine position with the neck in a neutral position. Palpate the thyroid notch, cricothyroid membrane, and the sternal notch for orientation. Surgically prepare and anaesthetize the area (if there is time and the patient is conscious).

• Stabilize the thyroid with the left hand. Make a transverse skin incision over the cricothyroid membrane. Carefully incise through the membrane. Insert the scalpel handle into the incision and rotate it 90° to open the airway. Insert an appropriately-sized, cuffed ETT or tracheostomy tube into the cricothyroid membrane incision, directing the tube inferiorly into the trachea. Inflate the cuff and ventilate the patient (Fig. 1.3 and Fig. 1.4).

Conscious patients with a compromised airway will often shows signs of agitation and will not want to lie supine as this causes the tongue to fall back into the airway. There may also be stridor present and signs of ↑ respiratory effort. Hypoxia may reveal itself by:

• Agitated patient.

• Varying level of consciousness.

• Inappropriate behaviour.

• Signs of airway compromise.

• Combination of these points.

Spinal immobilization

Patients with suspected spinal injuries or patients who are unconscious should be immobilized in the in-line spinal position. The cervical spine can be immobilized at the same time as establishing an airway.

Moving the patient

Multiple-injury patients should be immobilized on a spinal board for the purposes of transfer.

Intravenous access

Intravenous (IV) access should be established with two large-bore cannula (brown 14G or grey 16G) at two peripheral sites, such as the ante-cubital fossae.

Fig. 1.3 Cricothyroidotomy: surface landmarks.

Fig. 1.4 Cricothyroidotomy: airway secured with ETT.

Facial bleeding

Sitting the patient up not only improves the airway and breathing, but also reduces venous pressure with a consequent beneficial effect on bleeding from injury. Most facial bleeding from soft tissue injuries can be controlled with direct pressure. Torrential haemorrhage from mid-facial fractures is not so easily controlled. Anterior and posterior nasal packing is used to staunch haemorrhage from the nose. It is often also helpful to prop the mouth open, impacting the maxilla against the skull base and compressing bleeding vessels. Hypovolaemia may be clinically apparent by:

• Tachycardia.

• Tachypnoea.

• Anxiety.

• Peripheral vasoconstriction (cool clammy periphery, prolonged capillary refill).

The first priority in the presence of appreciable facial haemorrhage always remains protection of the airway.

Bleeding from the neck

• Bleeding from penetrating neck trauma is potentially serious.

• Neck is divided into three zones:

• zone I (base)—thoracic inlet to cricoid cartilage (highest mortality);

• zone II (mid-portion)—cricoid cartilage to angle of mandible;

• zone III (superior)—angle of mandible to skull base (difficult to access surgically).

External haemorrhage

If the haemorrhage is external, then local temporary measures such as isolating the bleeding point with a haemostat are appropriate. Bleeding from the tissues overlying the mandible from the facial artery can be controlled by pressure. Bleeding from the major vessels in the neck, such as the internal jugular vein, cannot be so easily controlled by pressure and will need prompt surgical exploration.

Concealed haemorrhage

Penetrating neck trauma from sharp implements, such as knives, can cause internal bleeding from damage to the great vessels without signs of external haemorrhage. This is potentially serious, as the consequences of rapid neck swelling can be fatal. Patients showing signs of neck swelling or patients who show signs of haemodynamic instability should have protection of the airway and control of haemorrhage. Imaging of the neck may be appropriate if time allows and angiography and embolization should be borne in mind as possible treatment options. Patients with penetrating injuries at the upper and lower third of the neck should also have imaging of the chest.

Imaging

• Plain films of neck.

• Chest X-ray (CXR).

• Computed tomography angiography (CTA).

• Conventional angiography.

• Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/magnetic resonance angiography (MRA).

• Ultrasound scanning (USS).

Initial management of head injuries

Patients with head injuries can initially be assessed using the ‘Alert, Voice, Pain, Unresponsive’ (AVPU) system before formal GCS assessment.

AVPU

| A | Alert. |

| V | Voice, able to respond to verbal command. |

| P | Does not respond to verbal command, will respond to pain. |

| U | Unresponsive. |

The first priority is to prevent secondary brain injury from inadequate cerebral circulation.

• Airway:

• provide 100% oxygen;

• consider intubation in the presence of hypoxia, hypercapnia, respiratory distress, or in a patient unable to protect their own airway.

• Breathing: assess and treat chest injuries.

• Circulation:

• evaluate and treat hypovolaemia;

• identify and control haemorrhage;

• use isotonic fluids (crystalloid now shown to be fluid of choice usually 0.9% saline);

• increasing use of permissive hypotension.

Glasgow Coma Scale

↓ level of consciousness as assessed by GCS.

Best eye response (E)

There are four grades starting with the most severe:

• Grade 1: no eye opening.

• Grade 2: eye opening in response to pain (patient responds to pressure on fingernail bed; if this does not elicit a response, supraorbital and sternal pressure or rub may be used).

• Grade 3: eye opening to speech (not to be confused with an awaking of a sleeping person; such patients receive a score of 4, not 3).

• Grade 4: eyes opening spontaneously.

Best verbal response (V)

There are five grades, starting with the most severe:

• Grade 1: no verbal response.

• Grade 2: incomprehensible sounds (moaning, but no words).

• Grade 3: inappropriate words (random or exclamatory articulated speech, but no conversational exchange).

• Grade 4: confused (patient responds to questions coherently, but there is some disorientation and confusion).

• Grade 5: orientated (patient responds coherently and appropriately to questions such as name and age, etc.).

Best motor response (M)

There are six grades, starting with the most severe:

• Grade 1: no motor response.

• Grade 2: extension to pain (adduction of arm, internal rotation of shoulder, pronation of forearm, extension of wrist—decerebrate response).

• Grade 3: abnormal flexion to pain (adduction of arm, internal rotation of shoulder, pronation of forearm, flexion of wrist—decorticate response).

• Grade 4: flexion/withdrawal to pain (flexion of elbow, supination of forearm, flexion of wrist when supraorbital pressure applied, pulls part of body away when nail bed pinched).

• Grade 5: localizes to pain (purposeful movements towards painful stimuli, e.g. hand crosses mid-line and gets above clavicle when supraorbital pressure applied).

• Grade 6: obeys commands (patient carries out simple requests).

A fully conscious patient scores 15. A patient scoring <8 should be considered to be in a coma and, as such, unable to protect their own airway. The minimum score is 3.

Computed tomography imaging in head injury

Criteria for immediate request for CT scan of the head (adults; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)):

• GCS <13 on initial assessment in the emergency department.

• GCS <15 at 2h after the injury on assessment in the emergency department.

• Suspected open or depressed skull fracture.

• Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, ‘panda’ eyes, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the ear or nose, Battle’s sign).

• Post-traumatic seizure.

• Focal neurological deficit.

• More than one episode of vomiting.

• Amnesia for events >30min before impact.

Criteria for immediate request for CT scan of the head provided patient has experienced some loss of consciousness or amnesia since the injury (adults):

• Age 65 years or older.

• Coagulopathy (history of bleeding, clotting disorder, current treatment with warfarin).

• Dangerous mechanism of injury (a pedestrian or cyclist struck by a motor vehicle, an occupant ejected from a motor vehicle, or a fall from a height of >1m or five stairs).

Criteria for immediate request for CT scan of the head (children):

• Loss of consciousness lasting >5min (witnessed).

• Amnesia (antegrade or retrograde) lasting >5min.

• Abnormal drowsiness.

• Three or more discrete episodes of vomiting.

• Clinical suspicion of non-accidental injury.

• Post-traumatic seizure but no history of epilepsy.

• GCS <14, or for a baby <1 year GCS (paediatric) <15, on assessment in the emergency department.

• Suspicion of open or depressed skull injury or tense fontanelle.

• Any sign of basal skull fracture (haemotympanum, ‘panda’ eyes, CSF leakage from the ear or nose, Battle’s sign).

• Focal neurological deficit.

• If <1 year, presence of bruise, swelling, or laceration of >5 cm on the head.

• Dangerous mechanism of injury (high-speed road traffic accident either as pedestrian, cyclist, or vehicle occupant; fall from a height of >3m; high-speed injury from a projectile or an object).

Initial management of ocular injuries

A high proportion of patients with orbital injuries will have coexisting ocular injuries. It is essential to make an initial basic assessment of ocular function. In a conscious patient, this should consist of an assessment of visual acuity using a pocket Snellen chart. If the patient cannot read the bottom line on the Snellen chart, then assessment is as follows:

• Can the patient count fingers?

• Can the patient see hand movement?

• Has the patient any light perception?

Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) is an indication of damage to the visual system that is useful in an unconscious patient. It is assessed by the swinging light test in which a pen torch is alternatively shone into one eye and then the other. Swinging the torch from the normal eye to the affected eye results in bilateral pupillary dilatation (Marcus Gunn sign). The presence of a RAPD usually indicates damage to the retina or optic nerve.

Directly examine the eye for the following clinical features:

• Hyphema: blood in anterior chamber.

• Irregular pupil: sign of underlying ocular injury.

• Constricted pupil: consider coexisting opiate abuse.

• Dilated pupil: suspect optic nerve or retinal injury or cocaine abuse.

Retrobulbar haemorrhage

Retrobulbar haemorrhage is best thought of as an example of acute orbital compression syndrome as a result of an intraconal bleed. The commonest causes are orbital trauma or as a complication of orbital surgery. Haemorrhage causes ↑ pressure within the orbit, reducing flow in the retinal artery (an anatomical end-artery), which in turn leads to irreversible vascular changes within the optic nerve, resulting in visual loss. Consider retrobulbar haemorrhage if:

• Tense proptosed eye: eye pushed forward under pressure compared with contralateral eye.

• Ophthalmoplegic eye: no eye movement.

• Chemosis and orbital pain.

• RAPD.

• Raised intra-ocular pressure.

• Retinal signs:

• papilloedema;

• lack of central retinal artery pulsation;

• pale optic disc (occurs late);

• cherry red macula.

Treatment of retrobulbar haemorrhage needs to be prompt in order to avoid permanent visual loss.

Treatment options

Medical decompression

• Mannitol (osmotic diuretic) 20% 2g/kg IV over 5min.

• Dexamethasone 8mg IV.

• Acetazolamide (carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, reduces production of aqueous humour), 500mg IV and then 1000mg orally over 24h.

Surgical decompression

Lateral canthotomy and cantholysis.

Canthotomy technique

• Clean the area with sterile saline.

• Inject local anaesthetic (LA) into the lateral canthus.

• Apply a haemostat/clamp with one side anterior and one side posterior to the lateral canthus and advance until the rim of the bony orbit is felt.

• Clamp for 30–60s.

• Perform the lateral canthotomy by carefully cutting through the crushed, demarcated line to the orbital rim/lateral fornix to avoid traumatizing the orbit.

Cantholysis technique

• Grasp lower eyelid with forceps and pull outwards/downwards away from eye.

• Identify the canthal ligament by either inspection or palpation. Incise the inferior crus of the lateral canthal ligament with scissors to avoid traumatizing the orbit.

• Recheck the orbit for reduction in intra-orbital and intra-ocular pressure. If pressure is still high, dissect the superior limb of the canthal ligament in a similar fashion. Care should be taken to avoid any trauma to the lacrimal gland.

‘First aid’, antibiotics, and tetanus

Antibiotic usage

Indications for prophylactic usage of antibiotics in trauma include:

• Contaminated soft tissue injury.

• Mandibular fractures which are compound to the mouth.

• Surgical emphysema.

• Peri-operative surgical prophylaxis in ORIF.

The importance of prompt surgical debridement cannot be over-emphasized in the management of contaminated wounds and compound fractures. Without surgical debridement infection will eventually occur even with antibiotic prophylaxis. Antibiotic prophylaxis should therefore start promptly and continue until surgical debridement has occurred.

In the case of grossly infected wounds and systemic signs, such as rigor, pyrexia, and tachycardia, antibiotics should continue for at least 5 days.

The choice of antibiotic will depend upon local policy.

Bite injuries should be covered with co-amoxiclav.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is no longer routinely recommended for patients with CSF leaks.

Tetanus prophylaxis

Consideration of tetanus prophylaxis depends upon the status of the wound and immunization status of the patient (Table 1.1).

Adsorbed tetanus vaccine

• Adsorbed tetanus vaccine is given as 0.5mL by deep subcutaneous (SC) or intramuscular (IM) injection into the deltoid or gluteal muscle.

• A full course of adsorbed tetanus vaccine consists of three doses of 0.5mL at intervals of not less than 4 weeks, followed by two further doses.

• Tetanus vaccine must not be given to anyone who has received a reinforcing dose in the preceding year.

• Patients with impaired immunity who suffer a tetanus-prone wound may not respond to vaccine and may therefore require anti-tetanus immunoglobulin in addition.

Human tetanus immunoglobulin for prophylaxis

• Human tetanus immunoglobulin is given as 250IU in 1mL by IM injection into the deltoid or gluteal region.

• If >24h have elapsed since injury, or there is risk of heavy contamination, or following burns, the recommended dose is 500IU.

Tetanus vaccine and immunoglobulin must be given by separate syringes into separate sites.

Penicillin/metronidazole is the drug of choice for treatment of tetanus.

Table 1.1 Wound type and immunization status

Definitive diagnosis

Full assessment of the maxillofacial region requires careful examination of the soft and hard tissues.

Inspection: facial

Soft tissue

Facial soft tissue injuries should be carefully recorded.

A laceration is caused by blunt trauma—an incised wound caused by a sharp object.

The use of clinical photography is to be commended especially for complex lacerations. Such photographs may be needed for medicolegal purposes and are always a useful adjunct to planning revision surgery. Each laceration should have the following recorded:

• Contamination: the greatest influence on management is the presence or absence of wound contamination. Heavily contaminated wounds, regardless of size and depth, need debridement, which often needs to be completed under GA.

• Condition of wound margins:

• sharp clean cut edge—this results from sharp injury such as injury on a metal edge. These are simple to repair after appropriate debridement;

• serrated edge—this can implicate glass fractured in the aetiology of the wound; if so, exploration of the wound to locate and remove them is required;

• rounded edge—if the edge of wound is rounded then it is likely that the wound has arisen as a result of friction over a bony protuberance. This is the case for the common paediatric injuries, such as cuts on the forehead, eyebrows, and chin;

• necrotic edge—higher energy transfer to the wound causes irreversible damage to the soft tissue edge, such that it is dusky or black. Judicious trimming of wound edges needs to be considered in such cases.

• Size: measure length of the laceration with a ruler.

• Depth:

• up to dermal depth—abrasion;

• up to fat depth—laceration likely to require suture;

• muscle involvement—consider the possibility of facial nerve or parotid involvement (surface anatomy of parotid duct is middle third of line drawn from the tragus to the corner of the mouth). The buccal branch of facial nerve is always closely associated with the parotid duct. Repair of the facial nerve is indicated in wounds lateral to the lateral canthus.

• bony involvement.

• Orientation to relaxed skin tension lines: lacerations which are orientated in the direction of relaxed skin tension lines are likely to heal better than lacerations orientated away from relaxed skin tension lines.

The following signs of bruising raise suspicion of an underlying fracture:

• Bruising over the skin of the mastoid bone: ‘Battle’s sign’ (can indicate a base of skull fracture).

• Bilateral periorbital bruising: ‘Raccoon eyes’ (can indicate a fracture of base of the skull, naso-ethmoid region, frontal sinus, or Le Fort II/III fracture).

• Bilateral inner canthus bruising: can indicate of nasal bone fracture.

• Bruising overlying the lower border of the mandible: can indicate a mandibular fracture.

The presence of facial swelling should be noted, although it correlates poorly with the severity of the underlying bony injury. Swelling often masks underlying bony deformity as described:

Bony/cartilaginous deformity

• Evidence of deformity in the frontal and naso-ethmoid area:

• frontal bone deformity—this is most commonly seen in patients with fractures of the anterior wall of the frontal sinus. The appearance is of a midline depression in the area immediately above the supraorbital ridge;

• naso-ethmoidal deformity—this is often associated with frontal deformity. The classic appearance includes telecanthus, depression of nasal bridge, and elevation of the nasal tip.

• Nasal bone deformity: the nose is frequently disrupted in facial injuries. Anatomically, only the upper third of nose is bony. Nasal fractures often present with deviation of the nose.

• Evidence of malar flattening: the zygomatic bone forms most of the lateral and inferior orbital rim. Inferolateral to this is the prominence of the zygoma. Displaced fractures of the zygoma produce flattening of this area that it is easy to underestimate in the acute setting as facial swelling obscures the appearance.

• Evidence of zygomatic arch deformity:

• in-fracture of the arch of the zygoma—may be an isolated fracture of the arch or may be associated with an externally rotated zygomatic fracture;

• out-fracture of the arch of the zygoma—seen as bowing of the zygomatic arch. Often associated with posterior displacement and an internally rotated zygomatic fracture. This is an important clinical sign as bowing of the zygomatic arch is hard to correct surgically and, if left untreated, leads to persistent bony swelling overlying the zygomatic arch.

Inspection: oral

An examination of the mouth is mandatory since clinical signs indicating fractures of the maxilla and mandible are often reflected in intraoral changes that are not obscured by general facial swelling.

• Bruising: sublingual haematoma (Coleman’s sign) is highly suggestive of a mandibular fracture.

• Gingival lacerations: laceration of the gingivae in the lower jaw is suggestive of a mandibular fracture, and in the upper jaw is suggestive of a segmental maxillary fracture.

• Palatal bruising: indicates either a split palate or Le Fort fracture.

• Gross deformity of mandible.

• Disorders of occlusion (Fig. 1.5):

• anterior open bite—either bilateral mandibular condylar fracture or a posteriorly displaced Le Fort fracture;

• lateral open bite—the patient’s teeth meet normally on one side, but on the opposite side there is no contact. The most common cause for this is a mandibular condylar fracture on the contralateral side to the open bite.

Fig. 1.5 Step in occlusion with mandibular fracture.

Inspection: orbital

Swelling may obscure a full view of the patient’s eye. If this is the case, it is still important to obtain a basic assessment of visual function (see ![]() Initial management of ocular injuries, p. 16). Systematic examination of the orbit is as follows:

Initial management of ocular injuries, p. 16). Systematic examination of the orbit is as follows:

• Pupillary level: is the pupil at the same level as the opposite eye? If one eye is lower then a vertical orbital dystopia exists that may be the result of a zygomatic or orbital floor fractures.

• Antero-posterior eye position: are the eyes in the same position? Enophthalmos can be associated with internal orbital wall injury. Exophthalmos is one sign of retrobulbar haemorrhage (see ![]() Initial management of ocular injuries, p. 16).

Initial management of ocular injuries, p. 16).

• Intercanthal distance (normally same width as palpebral fissure): an increase in the intercanthal width (normal range in Caucasians 28–35mm) results from lateral displacement of the medial canthal tendon. The result is telecanthus. The usual cause is a naso-ethmoidal fracture.

Inspection: nasal

The nose should be examined externally and internally. Internal examination of the nose is facilitated by the use of a Thuddicum’s speculum.

• External nasal examination: look for deviation of the nose and asymmetry of nasal bones.

• Internal nasal examination:

• septal haematoma—this is seen as a bulge on both sides of the nasal septum that often totally obscures the nasal airway. It is a surgical emergency and requires immediate drainage to prevent long-term damage to the septal cartilage;

• septal deviation/dislocation—this is common and should be elicited during the initial examination. Acute management may be required.

• CSF rhinorrhoea: this is seen as clear fluid leaking from the nose (detected by beta-2 transferrin assay). It occurs in high-level mid-face injuries, as well as naso-ethmoidal and frontal bone injury. The fluid is often seen tram lining—blood leaking from the nose forms clotted streaks of blood down the face with CSF washing away the central portion of clotted blood.

Inspection: ear

Inspect the pinna for signs of laceration and haematoma.

• Haematoma of the pinna can compromise the blood supply to the underlying cartilage producing a ‘cauliflower’ ear. These haematomas need drainage.

• CSF otorrhoea.

• Bleeding from the external auditory meatus: this can result from a number of injuries:

• base of skull fracture—Battle’s sign usually coexists;

• laceration of the cartilaginous auditory meatus—can be a sign of mandibular condylar injury;

• bleeding from tympanic membrane—usually associated with rupture of the tympanic membrane.

Active range of movement

Mandibular

Normal mandibular opening is around 35–45mm. Reduced mandibular opening is not a reliable indicator of mandibular fracture, since it can be secondary to soft tissue injuries and effusions of the temporomandibular joint. A more accurate clinical sign is the amount of protrusion of the mandible (activity of the lateral pterygoid muscles attached to head of the mandibular condyles).

Ocular

Examine the eyes in primary gaze (looking straight ahead), as well as the other eight positions of gaze (left and right central; left, central, and right upward gaze; left, central, and right downward gaze). Patients may report double vision.

• Monocular: lens dislocation or retinal detachment.

• Binocular:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses