Chapter 9 CPAP, APAP and BIPAP

1 INTRODUCTION

Positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy, including continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), adjustable positive airway pressure (APAP), and bi-level positive airway pressure (BI-PAP), is an important, non-invasive treatment for sleep disordered breathing (SDB). PAP therapy as a treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was first developed by Colin E. Sullivan and colleagues in 1980 at the University of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. The effectiveness of CPAP treatment first received public attention in 1981 when Sullivan published his findings, documenting that low pressures of air delivered through the nasal passages had the ability to splint the airway and provide a night of unobstructed, uninterrupted sleep, while reducing daytime somnolence.1 The recommended and only treatment available for OSA before Sullivan’s discovery was the surgical procedure of tracheotomy. Therapy models for PAP treatment have been incorporated into medical practices utilizing a variety of techniques. While surgical procedures are invasive and have variable success for OSA, PAP therapy has proven to be an effective treatment that corrects the obstructed airway, reduces the severity of SDB symptoms and the occurrence of associated co-morbidities, and has no associated risks, although compliance although remains an issue. In any case it is the first-line treatment for OSA. This chapter provides a description of how PAP is administered and a review of its history and efficacies.

2 OBJECTIVES OF PAP THERAPY IN AN ENTPRACTICE

Surgeons are understandably interested in surgical therapies for treating OSA. However, to nurture patient referrals, ENT physicians need to incorporate PAP treatments into their practice. Medical colleagues do not always have the resources or interest to examine the upper respiratory tract, diagnose SDB, and recommend appropriate patients for surgical consultations. Unfortunately, the medical community is disenchanted with surgical therapies in treating SDB due to a glaring absence of EBM Level I prospective, controlled studies demonstrating the benefit of surgery.2 Level II studies are also missing. Furthermore, the sleep physician’s anecdotal experience with surgery is not excellent for they rarely see the successes, but all too often see the failures. It is therefore the authors’ opinion that if ENT physicians choose to participate in the evaluation and management of SDB, they must offer not only home sleep testing, but also PAP administration as part of their sleep services. Currently, surgeons enjoy patient and primary care physician referrals, but if we are to maintain a position in the sleep market and retain and nurture a steady flow of patients, we must provide comprehensive services. This includes sleep testing and PAP administration in addition to our history, physical examination and surgical procedures. Setting up and managing a poly-somnographic operation is time consuming and complex. It is also expensive for patients, insurance companies, and the greater healthcare system.

Shown by numerous validation studies, multi-channel home sleep testing has proven to be highly correlated with polysomnography and equally effective in diagnosing OSA.3–6 Home sleep testing is easy to perform and fairly reimbursed. PAP therapy is more difficult to perform and is poorly reimbursed. However, if the head and neck surgeon does not provide PAP services, they will not have a comprehensive SDB practice and will ultimately lose their position in the sleep market. There was a time when allergists wished to become the entry point for patients with sinusitis. The head and neck surgery community countered, and today, patients with chronic sinusitis come to our office for evaluation, medical and surgical therapies. The authors propose that the diagnosis and treatment of OSA must follow a similar path in establishing itself within the medical community.

3 THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS

Surgical indications for the treatment of sleep disordered breathing are for the individuals who suffer from severe nasal obstruction, most notably nasal polyps, and the patients with four plus tonsils, Friedman Stage 1.7 Unfor-tunately, the majority of SDB is obstruction at the tongue base, an area where surgical therapy is not yet uniformly successful. Therefore, a large number of individuals with SDB must be provided PAP therapy, and only if this truly fails, be considered for surgical interventions. The senior author generally advises patients he will only discuss surgical therapies after the SDB patient has learned to use CPAP, and then makes an informed decision to pursue surgical options. Snoring, absent OSA, is still a surgical disease.

The indications for positive airway pressure therapy are individuals with significant SDB. The Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) guidelines indicate PAP therapy for individuals with an Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) of 15 events per hour or greater or an AHI of five or greater with two or more co-morbidities.8 Co-morbidities are listed in Table 9.1. There are many individuals with an AHI of five but less than 15, who are diagnosed with mild OSA, for whom PAP therapy should be recommended. This group would include those who are symptomatic, most notably presenting with excessive daytime sleepiness, hypertension and cardiovascular co-morbidities, and those who are not surgical candidates. With the prevalence of obesity increasing, the number of those patients will increase over time.

| Category | Condition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Hypertension Congestive heart failure Ischemic heart disease Dysrhythmias |

35, 36 37–41 42–46 47–49 |

| Respiratory | Pulmonary hypertension | 50 |

| Neurologic | Stroke Headache |

51–53 54, 55 |

| Metabolic | Insulin resistance Metabolic syndrome |

56–58 59, 60 |

| Gastrointestinal | Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 61–64 |

| Genitourinary | Erectile dysfunction Nocturia, enuresis |

65, 66 67, 68 |

4 ENT PRACTICE MODEL

4.1 AUTO-TITRATING PAP

Those who utilize laboratory polysomnography will often initiate PAP therapy from their lab. This is done through a split night titration, where PAP therapy is administered half way through a polysomnography sleep test if the sleep technician believes the patient is positive for SDB. A median pressure is titrated and prescribed for a CPAP machine. Those who conduct multi-channel home sleep testing and provide all their services out of their office can do the same with auto-PAP home titrations. Introduced to the market in 2000, auto-PAP machines have the ability to automatically adjust pressure settings throughout a night’s sleep to ensure that the correct pressure is being emitted to splint open the airway.9 There are several models of auto-adjusting PAP machines available in today’s market, and these are used for the initial titration and trial. They can also be used for the PAP treatment. Two recent models are seen in Figures 9.1 and 9.2.

An auto-titrating PAP machine is provided to a SDB patient who typically takes it home and uses it for 3–7 days. They then return the machine to the prescribing physician. If the patient and/or their insurance choose to provide an APAP machine, the prescription is written for the mask and the machine. If the insurance company only covers fixed pressure CPAP, the prescription also includes the 95th percentile pressure for the CPAP machine. This is the pressure that will splint the airway open 95% of the time. Fixed pressure CPAP does well, just not quite as well as APAP. The pros and cons of APAP versus CPAP are an evolving controversy. Typically, a durable medical equipment (DME) provider supplies the equipment. While some patients report immediate compliance and benefit, some experience difficulties. These individuals need to be seen in the office, their equipment adjusted, and compliance nurtured.

4.2 MASKS

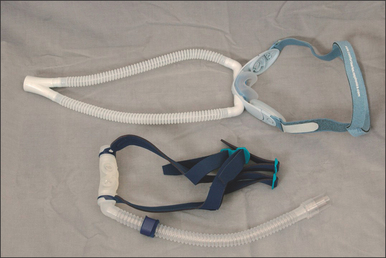

Numerous masks are available, and many believe the mask is the key to PAP therapy. Nasal masks are generally easier to use, as they are less intrusive and certainly less claust-rophobic, but individuals who are nighttime mouth breathers will require full face masks. There is no single mask to satisfy everyone, therefore an assortment of nasal masks and full face masks should be maintained. Figures 9.3 and 9.4 show several masks currently on the market. Patients can look at and try these in the office, and select a preference for model and size. The mask is also trialed with the auto-PAP machine for 3–7 days.

4.3 THE OFFICE VISIT

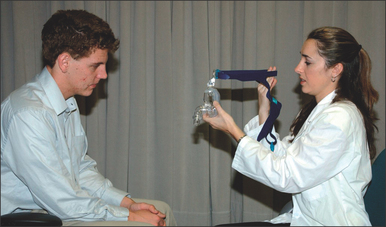

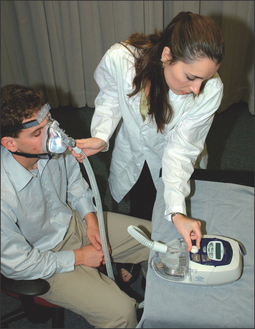

First and foremost, any lingering questions about the patient’s sleep study results should be addressed. The diagnosis and the importance of SDB as a health risk should be reiterated. Information in the form of pamphlets and handouts is an excellent supplement. To begin the PAP titration, the patient is asked if they are a mouth breather or a nasal breather to ensure that an appropriate trial mask is chosen. The titration/trial mask is then fitted to the patient and they are asked to practice putting it on their face, preferably in front of a mirror. Once the patient is comfortable handling the mask, it is connected to the titration PAP machine, and the starting procedure is demonstrated. The patient should spend a few minutes with the PAP machine on, to get an idea of how the pressure will feel. At the end of the appointment, logistical information about the PAP titration should be reviewed, and additional questions answered. This is a good time to hand out pamphlets and literature. A list of resourceful websites is generally helpful, as well as contact information, should difficulties arise. A patient should walk out of the PAP consultation with the confidence that the PAP treatment is important to their longevity and that this is a treatment they can do. Figures 9.5 to 9.10 demonstrate an office appointment for PAP fitting.

4.4 FOLLOW-UP AND COMPLIANCE TECHNIQUES

Many PAP therapy patients take one look at the mask and the machine and announce that they cannot use it. This does not constitute CPAP failure, and the physician and sleep technician must encourage patients to learn to use the PAP machine. Only once patients learn how to use PAP can they make an educated opinion about its long-term use. There are many tricks to nurture PAP use, and each practice needs to develop its own. During the 3–7 day trial, follow-up should be continuously maintained. The first night will be the most difficult for the majority of patients. A follow-up phone call should be made by the sleep technician to inquire about any difficulties the patient may have had with the PAP machine and the mask. At this time, suggestions can be made to nurture compliance. The first seemingly simple aid is to provide the patient with a sleeping pill for the first several nights. Lunesta®, while expensive and often not covered by insurance companies, is probably the preferred sleeping pill, for it is not addictive. Ambien® is an alternative. Tranquilizers and other medications are not ideal, as they will worsen the patient’s SDB, and if the patient does not use the PAP treatment, it will place them at risk for SDB difficulties, death included.

Some patients are claustrophobic and find the mask too frightening to wear. For these patients, a tranquilizer can be considered. Although time consuming, the best approach is probably to develop a program in which the patient slowly gets used to the mask and then the PAP machine. Our paradigm for the ‘difficult’ patient is to dispense the selected mask from the office and ask the patient to first wear it as an open mask without a hose and the PAP machine, just in the evenings and around their home. As they become used to this, then they can be asked to wear it during sleep. Once they are comfortable with the mask, the hose and PAP machine can be added. This can be started while awake and watching television and only after a few nights should they wear the PAP to bed. A second paradigm is to provide a PAP machine beginning at very low pressures, typically 4–6 cmH2O, increasing the pressure every couple of days until it reaches a therapeutic level. Another paradigm is to dispense an auto-adjusting PAP machine. Theoretically this only provides the required pressure to splint the sleeping airway, and is therefore unobtrusive. If the patient has difficulties, the maximum pressure can be turned down and then increased slowly. For those who experience drying, humidification can be added. In some cases, heated humidification is required. The humidifier seen in Figure 9.11 is typically an external attachment to the PAP machine. Humidification has its complexities, for the equipment and the tubing are prone to mold growth and therefore require a more aggressive daily cleaning program. The experienced PAP sleep technician and the DME can assist the patient in adopting a cleaning regime.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses