A cosmetic smile makeover has become a sought after procedure in our esthetically driven society. To promote patient satisfaction with treatment outcomes, all parties involved, including the patient, must be aware of the results that can be achieved and what it will require to achieve them. Although treatment can be redone, it cannot be undone. Therefore, much patient input must be solicited and considered before beginning treatment and before the final restorations are cemented. This article provides a treatment sequence that minimizes the possibility of an unhappy patient.

Key points

- •

A cosmetic smile makeover is a sought after procedure in our esthetically driven society, requiring participation of dental specialists, restorative dentists, and laboratory technicians.

- •

To promote patient satisfaction, all involved parties, including the patient, must be aware of the results that can be achieved and what it will require to achieve them.

- •

Although treatment can be redone, it cannot be undone; therefore, it is wise to solicit and consider patient input before treatment and before the final restorations are cemented.

Introduction

In practicing “cosmetic dentistry,” the dentist is often presented with a patient whose desire for esthetic improvement of their smile is mitigated by the fear of loss of control, and the unknown happiness with the final outcome. These concerns are beyond the simple reassurance by the dentist that “everything will turn out beautiful in the end.” During the consultation and before case acceptance, the dentist often shows the patient photographs of other cosmetic cases in an effort to convince the patient of their skill and talent. This, however, does not alter the patient’s concerns about whether they will be happy with their result. In addition, the dentist is faced with the possibility that the patient’s preconceived vision of a desirable outcome will not coincide with the dentist’s case-based restorative design. The dentist’s greatest fear should be that in the end and after measurably successful treatment, the patient may not be satisfied. This unfortunate result is a distinct possibility when the sequence of treatment is tooth preparation followed by temporary restorations that either conform to the original teeth, are generic in size and shape, or are nonpredictive of the final restorations. This treatment leaves the design of the final restorations completely in the hands of the ceramist, without input from the dentist or patient. With this treatment scenario the first time the patient sees their final smile they are bonded into place and they are handed a mirror. Fait accompli.

These difficulties are further exacerbated in a clinical presentation with desires for change that are not possible through restorative treatment alone. In these cases, consultation with other specialists must be a part of the initial workup to determine in advance the restorative plan and what the final outcome will be.

This case report takes a different approach to cosmetic treatment that ensures full communication between restorative dentist, dental specialists, laboratory ceramist, and, most important, the patient. Because the final result is never in doubt, both a happy patient and a happy dentist can be assured. As Steven Covey says in 7 Habits of Highly Successful People , “Begin with the end in mind.”

Case Presentation

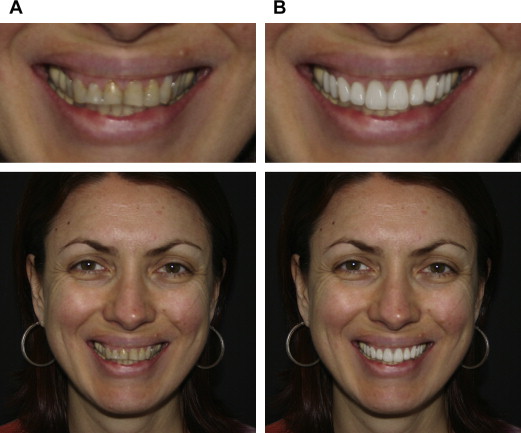

The patient, a 42-year-old Caucasian female, presented with a chief complaint of unhappiness with her smile ( Fig. 1 ). Consultation with the patient revealed apprehension about the result being natural in appearance and beautiful. The patient was assured that there would be no unhappy surprises as, using the method described herein, she would have input into every step of the process.

The cosmetic process began with a series of photographs, study models, digital radiographs, and completion of the NYU College of Dentistry Smile Evaluation Form. Evaluation of these records revealed no active caries and the presence of class III and class V restorations that would not interfere with treatment. The maxillary incisors were considerably worn and the lower incisors supererupted and in an edge-to-edge relationship with the maxillary teeth. The complete analysis indicated that orthodontic intervention would be necessary, followed by modification of the soft tissue surrounding the teeth to provide proper gingival heights and zenith points.

The initial photographs and models were shared with the orthodontist to determine the amount of movement that could be expected and the amount of clearance for the final restorations. This team approach is essential before developing any cosmetic plan to avoid an unrealistic and unachievable preview. A potential cosmetic design was determined using the orthodontist’s input, and guidelines developed for the optimal design of the dental smile. The “golden percentage” was used to determine the desired width of each of the teeth in the esthetic zone based on the full cuspid-to-cuspid distance when viewed from the facial aspect. Once the width was determined the position of the central incisors was established based on the reveal of the incisal edge at rest and its anterior–posterior location at the wet–dry line of the lip. It was necessary to ensure that this position fall within the interarch clearance that could be provided by the orthodontic movement. Using the width of the central incisor the length was determined using the ratio of 0.8/1 and the smile line established based on the central incisor position and the curvature of the lower lip during smiling. All of this information was put together as a proposed cosmetic design and sent for a computerized cosmetic preview (DaVinci Dental Laboratories; Fig. 2 ).

The computerized preview offers the advantage of allowing the patient to view the cosmetic changes that can be effected. At this point in the process, it would be impossible for the patient to preview the potential alterations by any other means. The potential hazard of this technique is to show changes that are, in fact, not possible clinically. Although a disclaimer is often shown on the bottom of these photographs, showing a patient changes that cannot be accomplished defeats the purpose of this communication and can lead to a very dissatisfied patient. The dentist using this technology must always do so with a firm clinical grasp of what can be accomplished and remain within those constraints.

The preview image was shown to the patient during a second consultation. This viewing affords the patient their first opportunity to see the proposed treatment result and opens a full discussion of their likes and dislikes. The size and shape of the teeth, the tooth color, tooth display while smiling, and incisal edge position are reviewed. It is a great advantage to have a computer program in the office that allows slight modification of the preview during this phase of consultation. For comparison, changes can be made, at the patient’s request, to 1 side of the smile. As the patient watches, they are drawn into the process. Once the patient is happy with the previewed result, the actual clinical phase of treatment was begun. It is important to realize that at this point the dentist and the patient both know where the final treatment will be taking them, while at the same time nothing irreversible had been done.

Introduction

In practicing “cosmetic dentistry,” the dentist is often presented with a patient whose desire for esthetic improvement of their smile is mitigated by the fear of loss of control, and the unknown happiness with the final outcome. These concerns are beyond the simple reassurance by the dentist that “everything will turn out beautiful in the end.” During the consultation and before case acceptance, the dentist often shows the patient photographs of other cosmetic cases in an effort to convince the patient of their skill and talent. This, however, does not alter the patient’s concerns about whether they will be happy with their result. In addition, the dentist is faced with the possibility that the patient’s preconceived vision of a desirable outcome will not coincide with the dentist’s case-based restorative design. The dentist’s greatest fear should be that in the end and after measurably successful treatment, the patient may not be satisfied. This unfortunate result is a distinct possibility when the sequence of treatment is tooth preparation followed by temporary restorations that either conform to the original teeth, are generic in size and shape, or are nonpredictive of the final restorations. This treatment leaves the design of the final restorations completely in the hands of the ceramist, without input from the dentist or patient. With this treatment scenario the first time the patient sees their final smile they are bonded into place and they are handed a mirror. Fait accompli.

These difficulties are further exacerbated in a clinical presentation with desires for change that are not possible through restorative treatment alone. In these cases, consultation with other specialists must be a part of the initial workup to determine in advance the restorative plan and what the final outcome will be.

This case report takes a different approach to cosmetic treatment that ensures full communication between restorative dentist, dental specialists, laboratory ceramist, and, most important, the patient. Because the final result is never in doubt, both a happy patient and a happy dentist can be assured. As Steven Covey says in 7 Habits of Highly Successful People , “Begin with the end in mind.”

Case Presentation

The patient, a 42-year-old Caucasian female, presented with a chief complaint of unhappiness with her smile ( Fig. 1 ). Consultation with the patient revealed apprehension about the result being natural in appearance and beautiful. The patient was assured that there would be no unhappy surprises as, using the method described herein, she would have input into every step of the process.