A 26-year-old woman was referred to a periodontal surgical practice for concerns related to gingival recession. After several consultations among the orthodontist, periodontist, and cosmetic/restorative dentist, she decided to have surgically facilitated orthodontic therapy as part of a collaborative, interdisciplinary treatment planning process to correct her constricted maxillary arch form, augment thin dentoalveolar facial bone, simultaneously with gaining root coverage as well as improving attached gingiva width and mucogingival thickness. As a consequence of changing the arch form, an improvement in the buccal corridor space was gained which optimized her smile display.

Key points

- •

Surgically facilitated orthodontic therapy can be an integral part of a comprehensive, interdisciplinary dentofacial therapy treatment plan that simultaneously addresses periodontal conditions, cosmetic/esthetic restorative space appropriation dilemmas, occlusion, and possibly airway-related improvements.

- •

Clear, consistent, and ongoing communication among restorative/cosmetic dentists, surgical specialists (dental and medical), patient, and family is essential to achieve optimal treatment outcomes.

Case presentation

Patient Background

A healthy 26-year-old white woman presented to the restorative practice for esthetic improvement to her smile. She had resin-bonded veneers on teeth numbers 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12 and a resin-bonded Maryland bridge between numbers 9 and 11, spanning a unilateral alveolar oronasal fistula that was a sequel of unsuccessful unilateral cleft palate repair when she was 1 year old ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). She was dissatisfied not only with the deteriorating esthetics of these restorations (which had been in place for approximately 10 years) and shifting of the bridge but also with her overall smile esthetics, and she desired improvement.

Medical history

The patient was in good systemic health. Her medical history was unremarkable except for asthma, seasonal allergies, and a history of eczema. Her current medications included montelukast sodium, cetirizine, mometasone furoate monohydrate nasal spray, and eye drops (allergy related), which she took to manage her allergic/asthmatic symptoms.

Dental history

The patient was born with a left unilateral cleft lip and palate. Although the lip repair was successful at age 3 months, the attempted closure of the bony palatal cleft at age 1 year was not. The remaining bony and soft tissue defect extended through the alveolar process and oral mucosa, leaving an alveolar communication between the oral and nasal cavities (oronasal fistula) in the number 10 position.

The craniofacial defect created by the unilateral (left) maxillary cleft resulted in an hourglass-shaped upper arch form and a bilateral crossbite ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). She was originally seen by the treating periodontist in 2004 for management of a recession defect, which was corrected by a connective tissue graft alone via a tunneling procedure.

Following connective tissue graft healing, her dentist at that time managed cosmetic concerns by composite bonding in the anterior maxilla.

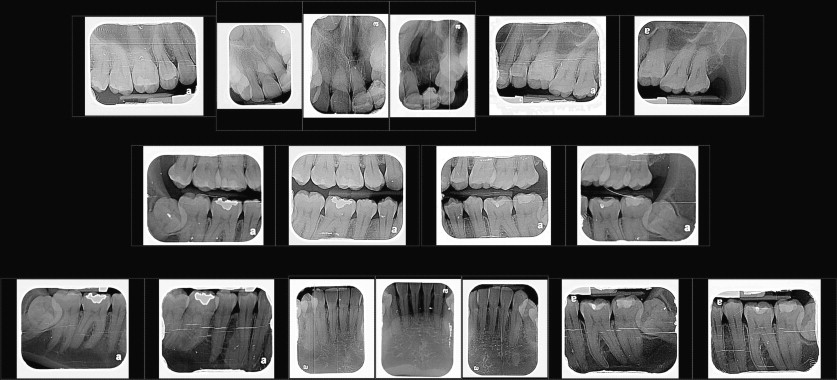

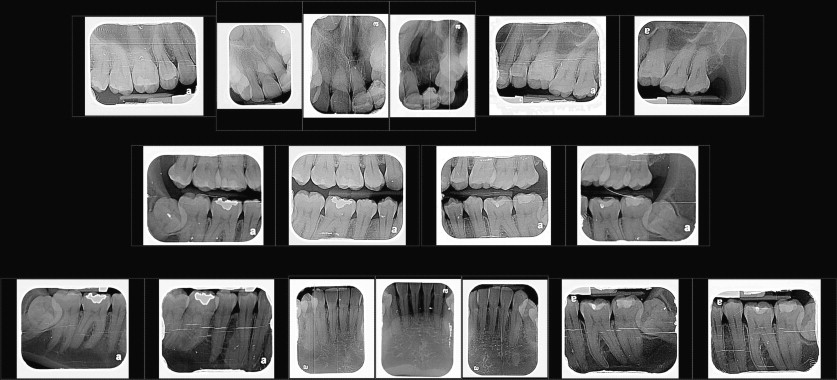

Figs. 5–7 show the pretreatment appearance of the dentition at roughly 6 years after treatment, showing the resin-bonded bridge in place at the start of current treatment (see Figs. 1–4 ). Fig. 8 shows a full-face pretreatment view of the patient; Fig. 9 shows her initial full-mouth radiographic series from February 2010. The relapse in recession underscores the biological short-coming of connective tissue grafting for root coverage purposes, which results in a long-junctional epithelium compared with the more desirable outcome of periodontal regeneration (cementum, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament).

She had undergone 2 previous periods of orthodontic treatment, during which teeth numbers 4 and 13 were extracted, and numbers 1 and 16 were retained (numbers 17 and 32 are retained and impacted). The resulting occlusion comprised an Angle class II molar relationship on the right ( Fig. 10 ), and a class I relationship on the left (in the area of the cleft-related arch deficit; Fig. 11 ). Her history also included alveolus repair, palate repair including velopharyngeal flap, rib grafting (as part of the attempted cleft repair), and alar and lip revisions; a noticeable alar discrepancy remains on the left side (see Figs. 1 , 3 , and 8 ).

Overall, her oral hygiene was good, and she remains on a preventive recall schedule with adult prophylaxis and oral examination at 6-month intervals.

Case presentation

Patient Background

A healthy 26-year-old white woman presented to the restorative practice for esthetic improvement to her smile. She had resin-bonded veneers on teeth numbers 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12 and a resin-bonded Maryland bridge between numbers 9 and 11, spanning a unilateral alveolar oronasal fistula that was a sequel of unsuccessful unilateral cleft palate repair when she was 1 year old ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). She was dissatisfied not only with the deteriorating esthetics of these restorations (which had been in place for approximately 10 years) and shifting of the bridge but also with her overall smile esthetics, and she desired improvement.

Medical history

The patient was in good systemic health. Her medical history was unremarkable except for asthma, seasonal allergies, and a history of eczema. Her current medications included montelukast sodium, cetirizine, mometasone furoate monohydrate nasal spray, and eye drops (allergy related), which she took to manage her allergic/asthmatic symptoms.

Dental history

The patient was born with a left unilateral cleft lip and palate. Although the lip repair was successful at age 3 months, the attempted closure of the bony palatal cleft at age 1 year was not. The remaining bony and soft tissue defect extended through the alveolar process and oral mucosa, leaving an alveolar communication between the oral and nasal cavities (oronasal fistula) in the number 10 position.

The craniofacial defect created by the unilateral (left) maxillary cleft resulted in an hourglass-shaped upper arch form and a bilateral crossbite ( Figs. 3 and 4 ). She was originally seen by the treating periodontist in 2004 for management of a recession defect, which was corrected by a connective tissue graft alone via a tunneling procedure.

Following connective tissue graft healing, her dentist at that time managed cosmetic concerns by composite bonding in the anterior maxilla.

Figs. 5–7 show the pretreatment appearance of the dentition at roughly 6 years after treatment, showing the resin-bonded bridge in place at the start of current treatment (see Figs. 1–4 ). Fig. 8 shows a full-face pretreatment view of the patient; Fig. 9 shows her initial full-mouth radiographic series from February 2010. The relapse in recession underscores the biological short-coming of connective tissue grafting for root coverage purposes, which results in a long-junctional epithelium compared with the more desirable outcome of periodontal regeneration (cementum, alveolar bone, and periodontal ligament).