Fig. 3.1

Typical facial appearance of Coffin-Lowry syndrome

Oral features associated with Coffin-Lowry syndrome include both soft and hard tissues. Soft tissue features include a furrowed tongue and thick lips [8]. Also noteworthy are mandibular prognathism, high vaulted palate, microdontia, and premature exfoliation of primary teeth [1, 8–10]. These primary teeth exfoliate without root resorption since the pathological mechanism appears to be hypoplastic cementum [10].

The presentation of dental findings may aid in the diagnosis but the spectrum of clinical features make it likely the diagnosis would be made prior to the presentation to the dental professional. Treatment includes palliative care with extraction of mobile symptomatic teeth along with aggressive oral hygiene practices [8].

Hajdu-Cheney Syndrome

Hajdu-Cheney syndrome (OMIM #102500) is a rare progressive disorder of bone metabolism which results in a dissolution of the hand’s and feet’s terminal phalanges [11, 12]. It demonstrates an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance due to mutations in the NOTCH2 gene that is an important regulator of gene expression. Hajdu-Cheney syndrome is characterized by a variable cluster of clinical manifestations affecting skeletal and other tissues [1, 11, 12].

The clinical features of this syndrome are quite obvious. In addition to the bony dissolution in the hands and feet, patients with Hajdu-Cheney also demonstrate joint laxity, short stature, scoliosis, kyphosis, and multiple osteolytic lesions [1, 11, 12].

These children also present with characteristic facial features. The craniofacial features, although not pathognomonic, are relatively distinctive. These features include an elongated skull with a widened sella turcica, absence of a frontal sinus, small chin, and a dolichocephalic appearance [11, 12]. Coarse hair, thick eyebrows, and clubbing of the fingers are also seen [11].

Oral features in Hajdu-Cheney include both hard and soft tissue pathology. Inflammation of the gingiva with bleeding on probing is present. An underlying periodontitis with atrophy of the alveolar bone also occurs [11]. The hard tissue changes that have been reported include hypoplastic roots along with structural changes in the cementum and dentin which results in premature tooth loss [11, 12].

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos (OMIM #130090) represents a group of inherited disorders that are caused by mutations in the genes that code for different collagens and a variety of other proteins. Patients with Ehlers-Danlos demonstrate hyperextensible skin along with hypermobility of the joints of their digits [1, 13, 14]. The underlying pathological mechanism of this condition is related to a disordered collagen metabolism. Multiple subtypes have been recognized resulting in a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 live births for this autosomal dominant condition [1, 13, 14].

The reported dental changes are also related to the abnormal collagen metabolism and vary between the different subtypes. This disordered metabolism is thought to result in enhanced resorption of the crest of the alveolar bone and apices of the roots [13]. In addition, fragility of the oral mucosa and blood vessels, along with the concomitant aggressive periodontitis, results in severe alveolar bone loss with related tooth loss. Inflamed gingiva is also readily seen [13].

The primary goal of the indicated dental treatment is to control the disease and subsequent tooth loss. Unfortunately targeting oral hygiene alone does not produce enough of an impact to control the loss of clinical attachment which leads to the premature exfoliation of the teeth. It has also been reported that orthodontic treatment can exacerbate this bone loss [13, 14].

Papillon-Lefevre Syndrome

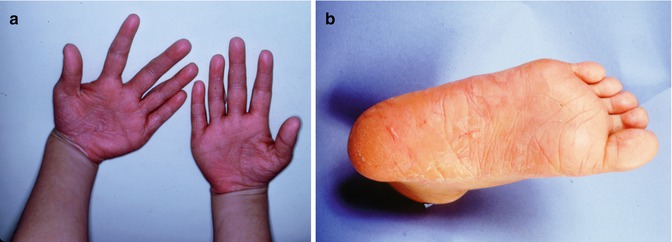

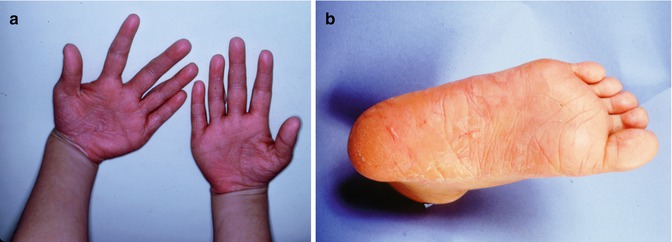

Papillon-Lefevre syndrome (OMIM #245000) is caused by mutations in the cathepsin C gene that codes for a protein with important function in immune cells. Perhaps the most striking clinical feature of this syndrome, and something that is diagnostic for this condition, is the hyperkeratosis of the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet (Fig. 3.2a, b) [1, 3, 15–18]. This rare genetic disorder follows an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance and is seen equally in males and females with an incidence of one to four per million live births having been reported [1, 15–18].

Fig. 3.2

(a) and (b) Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis as seen in Papillon-Lefevre syndrome

The onset of the associated dental changes coincides with the eruption of the primary teeth and with the start of the hyperkeratosis [17]. The premature loss of teeth, which can affect both dentitions, is related to the severe periodontitis and bone loss. The gingiva is hyperemic and edematous with deep periodontal pocketing [15, 18]. The teeth become progressively more mobile resulting in discomfort with eating [16]. Dental radiographs taken on these patients demonstrate generalized alveolar bone destruction associated with the primary dentition [16].

Although a diagnosis of Papillon-Lefevre syndrome can be made histologically from biopsies from the skin of the hands and feet, it is usually made based on the clinical presentation and genetic testing [18]. Clinically, the three features required for a diagnosis are [18]:

1.

Autosomal recessive inheritance

2.

Palmoplantar hyperkeratosis

3.

Loss of the primary and permanent dentitions

A multifaceted treatment approach is required for Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. Treatment usually consists of four components: (1) aggressive professional in-office care (2), treatment of involved symptomatic teeth (3), excellent home care and oral hygiene, and (4) antibiotics. In-office care includes periodontal debridement along with scaling and root planing. Extraction of hopeless teeth should also be performed. In some cases early full-mouth extraction of the primary teeth is recommended so that the permanent teeth can erupt into a healthier environment [3, 17].

Outside of the dental office, treatment includes methods for aggressive local plaque control [15]. In addition antibiotics are sometimes used. The use of both broad-spectrum antibiotics and those aimed at specific identified organisms has been reported in the literature [3, 15, 17, 18]. Early treatment is important since it may aid in the retention of the permanent dentition [1].

Cherubism

Cherubism (OMIM #118400) is a rare condition that has an onset of between 2 and 4 years of age [1]. It is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait and it is known to have a highly variable expressivity [1, 3]. This is a fibroosseous condition characterized by osteoclastic degeneration of the upper and lower jaws followed by development of fibrous masses.

The two most common clinical features give rise to the typical facial appearance seen with cherubism. Involvement of the maxilla with displacement of the globes along with the bilateral mandibular swelling yields the characteristic facial appearance of these children [3]. These symmetrical mandibular swellings usually increase in size until puberty and stabilize and often regress after that [1, 18].

Radiographically these mandibular swellings present as multilocular radiolucent cystic lesions which can also be seen in the ribs [1, 3, 19]. These multilocular cysts can impact the overlying dentition (Fig. 3.3). They can cause displacement of the primary and permanent dentition. As these teeth become more mobile, there is resultant pain with the teeth eventually exfoliating. In some cases exfoliation of the primary dentition can occur as early as 22 months [1, 3, 19].

Fig. 3.3

Panoramic radiograph of a patient with cherubism. Multilocular lesions are evident in the mandible bilaterally

A diagnosis of cherubism is based on a combination of all findings including clinical, radiographic, and histological. A family history can also help with the diagnosis [19]. Treatment will vary depending on the needs of the affected individual. Surgical reduction of the bony lesions can be accomplished if the child is having psychosocial issues due to their appearance. While the lesions tend to regress after puberty, lesion regression may not occur until much later in life. Surgical treatment coupled with autogenous bone grafting and postoperative treatment to reduce osteoclast activities also have been reported [20].

Dental prostheses can be made to assist with mastication when teeth are lost due to progression of the fibroosseous lesions that can result in tooth displacement and loss.

Endocrine Conditions

Hypophosphatemia

Hypophosphatemia or hypophosphatemic rickets is an abnormality of renal tubular transport of phosphate that can present in various forms. These include X-linked (OMIM #307800), the autosomal dominant vitamin D-resistant forms (OMIM #193100), and the autosomal recessive inherited trait (OMIM #241520) [3, 21]. Clinical features often become evident by the second year of life and include short stature and boxed legs [3, 21].

Dentally these children have thin hypomineralized enamel along with large pulp chambers and high pulp horns which can result in pulp exposures even in the absence of dental caries. These pulp exposures can lead to spontaneous dental abscesses that result in bone loss and the early loss of primary teeth [3, 21].

Diagnosis will often be made by a physician prior to any dental examination. However, dental radiographs will indicate the enamel and pulp chamber changes already mentioned. In addition, changes in the trabeculation of the alveolar bone along with abnormal or absent lamina dura can be observed radiographically [3].

Treatment will depend upon the patient’s presentation. Patients will often be given vitamin D analogs and phosphate supplements to improve tooth and bone mineralization. Pulp therapy followed by full-coverage crowns is often indicated along with extraction of abscessed teeth. Despite these different interventions and treatment, dental management in patients with severe dental manifestations is challenging, and outcomes of these therapeutic approaches are not well documented.

Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism (OMIM #275000) is an autosomal dominant condition that results in an autoimmune reaction. Antibodies to the thyrotropin receptors are generated which results in an overproduction of thyroid hormone via a physiological feedback cycle. In the presence of preexisting periodontal bone loss, an increase in circulating thyroid hormone will result in an increase in the number of bone resorbing cells which in turn results in an increase in bone maturation and turnover. This accounts for the alveolar bone loss, premature exfoliation of the primary dentition, and an associated accelerated eruption of the permanent dentition [1, 22].

This increase in circulating thyroid hormone is also the etiological factor for the clinical features seen in hyperthyroidism. These include hyperactivity and emotional disturbances [1, 22]. Diagnosis would be based on blood work which would show an increased level of circulating thyroid hormone, and dental treatment would be based on the patient’s symptoms.

Hypophosphatasia

Hypophosphatasia is characterized by improper mineralization of bone secondary to defective or deficient alkaline phosphatase [1, 3, 15, 23]. This inheritable condition has multiple forms with different modes of inheritance including autosomal recessive and autosomal dominant transmission [1, 3, 24].

Although the three different forms of hypophosphatasia vary in prognosis, in general the earlier the disease manifests itself, the increased severity of the disease [1, 3]. The phenotypes for these forms vary from the mildest with premature loss of deciduous teeth to severe abnormalities of bone with neonatal death [15].

The three forms, which are based on age of onset, are infantile, juvenile or childhood, and adult [3, 25]. These three types of hypophosphatasia have historically been delineated based on the time of diagnosis and level of severity [3]:

1.

Infantile: autosomal recessive, usually lethal (OMIM #241500)

2.

Juvenile (or childhood): autosomal recessive, milder form (OMIM #241510)

3.

Adult: autosomal dominant, mildest (OMIM #146300)

The predominant dental finding in hypophosphatasia is mobility and premature loss of the primary teeth, most often the mandibular anterior [3, 25]. This tooth loss is usually spontaneous with the exfoliation being associated with a loss of alveolar bone along with defective or hypoplastic cementum (Fig. 3.4) [1, 3]. Alkaline phosphatase is critical for normal development of mineralized tissues, and hypophosphatasia results in abnormal cementoblast function and the cell’s ability to regulate pyrophosphates critical for normal tissue formation and mineralization during cementogenesis. This defective cementum results in a weakened tooth to alveolar bone attachment which in turn leads to the loss of the primary dentition [15]. This tooth loss is associated with minimal gingival inflammation and minimal plaque buildup (Fig. 3.5) [1, 14].

Fig. 3.4

Prematurely exfoliated teeth as seen in hypophosphatasia

Fig. 3.5

Minimal inflammation seen in the area of prematurely exfoliated teeth in a child with hypophosphatasia

Since the teeth are usually affected in the order that they are formed, teeth that are formed earlier are the teeth that are usually involved; this includes the mandibular anterior primary teeth [15]. It should be noted that posterior teeth can also exfoliate prematurely [23]. Additional dental findings that have been reported include enamel hypoplasia, enlarged pulp chambers and root canals, bulbous crowns, and delayed dentin formation [23, 24].

Hypophosphatasia can be diagnosed in two different ways. Laboratory tests can be used to determine the level of serum alkaline phosphatase. In hypophosphatasia a deficient serum and bone alkaline phosphatase activity is found [3, 15, 23]. An additional method of diagnosis involves histological examination of the cementum. Histological samples will indicate hypoplasia of the cementum to the point of a virtual absence of it, resulting in exfoliation of the primary dentition prior to root resorption [1, 23].

Recently, Whyte et al. [26] reported the results of a multinational, open-label study of treatment with ENB0040, a recombinant human tissue nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNSALP; 171760) coupled to a deca-aspartate motif for targeting, an enzyme replacement therapy for infantile hypophosphatasia. In this study 11 infants or young children with life-threatening hypophosphatasia were enrolled. Improvement in developmental milestones and pulmonary function along with the healing of bony changes was noted in nine patients after 6 months of therapy [26]. Management of this condition has until now been palliative in nature, aimed at the relief of symptoms often by the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications [15, 23]. Dental management emphasizes thorough prevention and oral hygiene regimens [23]. Although the prognosis for the affected primary teeth is poor, it is good for the permanent teeth as these are usually uninvolved [23]. It is not yet clear what the potential benefit of enzyme replacement therapy might be for the dental manifestations and timing of treatment may be problematic unless therapy is initiated during root formation so cementogenesis can progress normally.

Immunological Conditions

Prepubertal Periodontitis

With an onset by 4 years of age, prepubertal periodontitis exists in both localized and generalized forms [1]. The localized form presents with little gingival involvement, demonstrating few signs of inflammation [1]. In the generalized form, severe acute gingival inflammation and recession are noted around all of the primary teeth [1]. The destruction of alveolar bone in prepubertal periodontitis is more rapid than what is seen with the adult form [1].

The tooth loss exhibited in prepubertal periodontitis can be mistaken for that associated with hypophosphatasia. However in prepubertal periodontitis, which in girls is one of the most common reasons for premature exfoliation of the primary teeth, the children are seropositive for Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans [1].

Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency

This rare autosomal recessive disorder (OMIM #612840) is characterized by a defect associated with the white blood cells which results in a defect of their phagocytic function [13, 27–29]. The resultant defective or deficient surface protein causes poor leukocyte migration to the site of infection [15]. This leads to the impaired phagocytic function of the leukocytes and a subsequent increased risk of infection, including periodontitis [15, 22].

The clinical features of leukocyte adhesion deficiency are all related to this impaired leukocytic function. These children present with recurrent fungal and bacterial infections with impaired wound healing. Recurrent infections of the skin and otitis media are commonly seen along with necrotic infections of the gastrointestinal tract and mucous membranes [15, 27–29]. These skin infections are often without the formation of any purulence [29].

The pathologies within the oral cavity are all a function of a severe chronic infection. A severe periodontitis is present (Fig. 3.6) causing rapid alveolar bone loss. This early-onset periodontitis in the primary dentition, and the resulting rapid alveolar bone loss (Fig. 3.7) surrounding the primary teeth, is the cause of the early exfoliation of (in some cases) the entire primary dentition [15, 27–29]. A marked gingival inflammation is present around the affected teeth which includes both the primary and permanent dentitions [15, 28] (Table 3.1).

Fig. 3.6

Severe gingivitis and periodontitis associated with leukocyte defect

Fig. 3.7

Bone loss associated with the periodontitis seen with leukocyte defect

Table 3.1

Conditions associated with early exfoliation of primary teeth

|

Condition

|

Age of onset

|

Gingival inflammation

|

Physical findings

|

Oral findings

|

Radiographic findings

|

Etiology

|

Specific dental treatment

|

Add’t info

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acrodynia

|

Variable

|

Variable

|

Fever, sweating, anorexia, listlessness, irritability, tachycardia, hypertension

|

Inflammation and ulceration of mucous membranes

|

Alveolar bone loss

|

Exposure to medications with a mercury base in hypersensitive children

|

Palliative

|

|

|

Chediak-Higashi syndrome

|

Variable

|

Severe

|

Respiratory and skin infections, strabismus, nystagmus

|

Early onset and severe destruction of the periodontium

|

Destruction of alveolar bone

|

Autosomal recessive inheritance

|

Palliative

|

|

|

Singleton-Merten

|

Variable

|

Variable

|

Deformities of the hands and feel, joint subluxation, ruptured ligaments, muscle weakness, short stature, osteoporosis, idiopathic calcification of aortic valve and arch, glaucoma, infertility

|

Delayed eruption

|

Alveolar bone loss, delayed root formation, acute root resorption

|

Autosomal dominant inheritance

|

Palliative

|

|

|

Coffin-Lowry syndrome

|

Birth

|

Variable

|

Persistent anterior fontanel, thick hands, extensible joints, generalized hypotonia, sensorineural hearing loss, intellectual disabilities

|

Furrowed tongue, thick lips, mandibular prognathism, high vaulted palate, microdontia

|

Alveolar bone loss, no root resorption seen on mobile teeth

|

X-linked inheritance

|

Palliative, extraction of mobile symptomatic teeth, aggressive oral hygiene

|

Hypoplastic cementum present on the roots of affected teeth

|

|

Hajdu-Cheney syndrome

|

In childhood, actual age varies

|

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses