INTRODUCTION

Few areas of surgery have such a rich blend of controversy as that of cleft palate repair. There is disagreement with nearly every treatment aspect associated with cleft palate repair, from the utility of particular muscle repair techniques to timing choices. There is no shortage of publications on these issues and many other matters of cleft palate repair, but only a very small percentage of the published data is prospective and randomized. The vast majority of the literature is self-reported by centers or surgeons who favor particular approaches and therefore is riddled with bias. This makes the decision-making for our patients difficult, and by necessity filled with opinion-based therapies rather than those guided by level I evidence. This introductory section highlights the differences among the repair techniques and philosophies and provides summaries of the available outcome data. Given the current state of the art in cleft surgery, the published literature does not allow dogmatic comments to be made regarding cleft repair. Questions still remain to be answered, in large part because of the complexity and heterogeneity of patients with clefts. The study of these patients and their subjective outcomes is exceptionally difficult and continues to be a challenge for those of us interested in measuring results. Each of the popular techniques and philosophies has its advantages and disadvantages. Therefore, each section of this chapter is designed to highlight the advantages of a philosophy or technique and review the supporting literature.

The authors of this chapter reviewing cleft palate repair have been asked to address the issues associated with the repairs by breaking them down into three major groups: (1) two-flap procedures, (2) double-opposing Z-plasty procedures, and (3) staged cleft palate repair. All authors have been asked to highlight the literature and present their views on important factors that produce success. The section on two-flap procedures reviews the background information necessary for understanding some of the concepts and controversies associated with cleft palate repair and outlines the available outcomes. The double-opposing Z-plasty or Furlow repair has received considerable attention in recent years, and its supporters have reported impressive speech results. The benefits of this approach are reviewed by one of the world’s experts on this technique. The section on staged cleft palate repair reviews the philosophy of timing various portions of cleft repair to optimize growth. Obviously, a number of techniques can be used if practitioners stage a cleft palate repair, so this chapter highlights the philosophy more than details of surgical technique. The evident conclusion is that more comparative study is needed to completely understand the advantages and disadvantages of these different techniques and philosophies.

HISTORY

The first documented successful cleft palate repair was performed by a Parisian dentist, LeMonier, in 1766. Over the last century of cleft palate repair, the most popular repair has been the two-flap palatoplasty in various forms and with an assortment of modifications. Some of the more notable repair techniques have included the Wardill-Kilner pushback, the Bardach two-flap, and the von Langenbeck palatoplasties. A long history exists documenting these procedures as viable and successful for cleft palate repair. Like many procedure-based publications in surgery, almost all of these data have a case series design, are retrospective, and are self-reported. Few blinded, prospective, randomized studies exist in the literature, and currently there is no published level I evidence comparing the outcomes of the various procedures that allows clinicians to make clear choices based on powerful, compelling, and statistically significant evidence.

In 1978 Leonard Furlow introduced the double-opposing Z-plasty palatoplasty and described superior results when compared with his own experience using a two-flap technique. Since that time a large number of articles have been published purporting superior results with this technique. Since Furlow described his technique, a number of comparative studies have emerged, but none published to date stands up to the rigorous requirements of level I evidence. Notably, this is true regarding the other techniques as well. Most of these studies are case series that have a number of scientific flaws, not owing to lack of effort on the part of the researchers, but rather indicating the difficulty of studying of this heterogenous group of patients. Like much of surgical literature, almost all of these data are self-reported by the surgeons and/or centers that advocate the repair technique. In addition, measuring what is “good” speech becomes exceptionally difficult among different speech pathologists, even within the same center. Therefore to compare data from one group with data published by those who favor other techniques is not statistically valid.

An additional area of historical controversy is the philosophy of staged cleft palate repair. It was popularized by Schweckendiek in the 1970s, mostly in European centers. Whereas most of the centers in the United States do not adopt this philosophy of repairing the hard palate at a later date than the soft palate, a number of European and Asian centers have used this philosophy for decades. A number of these centers have published impressive data over many years supporting this approach. True comparative data are lacking in the literature.

HISTORY

The first documented successful cleft palate repair was performed by a Parisian dentist, LeMonier, in 1766. Over the last century of cleft palate repair, the most popular repair has been the two-flap palatoplasty in various forms and with an assortment of modifications. Some of the more notable repair techniques have included the Wardill-Kilner pushback, the Bardach two-flap, and the von Langenbeck palatoplasties. A long history exists documenting these procedures as viable and successful for cleft palate repair. Like many procedure-based publications in surgery, almost all of these data have a case series design, are retrospective, and are self-reported. Few blinded, prospective, randomized studies exist in the literature, and currently there is no published level I evidence comparing the outcomes of the various procedures that allows clinicians to make clear choices based on powerful, compelling, and statistically significant evidence.

In 1978 Leonard Furlow introduced the double-opposing Z-plasty palatoplasty and described superior results when compared with his own experience using a two-flap technique. Since that time a large number of articles have been published purporting superior results with this technique. Since Furlow described his technique, a number of comparative studies have emerged, but none published to date stands up to the rigorous requirements of level I evidence. Notably, this is true regarding the other techniques as well. Most of these studies are case series that have a number of scientific flaws, not owing to lack of effort on the part of the researchers, but rather indicating the difficulty of studying of this heterogenous group of patients. Like much of surgical literature, almost all of these data are self-reported by the surgeons and/or centers that advocate the repair technique. In addition, measuring what is “good” speech becomes exceptionally difficult among different speech pathologists, even within the same center. Therefore to compare data from one group with data published by those who favor other techniques is not statistically valid.

An additional area of historical controversy is the philosophy of staged cleft palate repair. It was popularized by Schweckendiek in the 1970s, mostly in European centers. Whereas most of the centers in the United States do not adopt this philosophy of repairing the hard palate at a later date than the soft palate, a number of European and Asian centers have used this philosophy for decades. A number of these centers have published impressive data over many years supporting this approach. True comparative data are lacking in the literature.

OUTCOMES

The concept of measuring best outcome is complicated for patients who undergo a cleft palate repair. There are a number of outcomes that may be considered important in cleft palate care, including the following:

- •

Speech (early and late results)

- •

Growth of the maxilla

- •

Occlusion

- •

Midfacial projection

- •

Maxillary arch form

- •

- •

Retention of permanent teeth

- •

Presence of fistula after repair

There is little argument that the two most important variables are speech and growth. Speech is the first of these outcomes to be addressed in a team fashion, and much time and energy are expended on maximizing speech outcome after cleft palate repair. Speech outcomes are noted early in child development and become important as children begin to communicate and enter society. However, long-term evaluations of speech in discrete populations, such as those with clefts, are hard to come by in the literature. From the limited published data available, there are notable changes in speech over the long-term. Changes in speech may be positive or negative and are difficult to predict over the long term. The challenge of evaluating speech at one point in time as well as over the long term in patients with clefts is described in the following paragraphs.

Over the past century of cleft care, long-term evaluations have determined that ignoring the biologic consequences of early surgery can be devastating to growth potential. Poor midfacial growth creates a host of problems for the young child and adolescent that affects esthetics and function. In addition, large discrepancies between the maxilla and mandible produce articulation disorders that create long-term speech issues independent of those that may occur at the velum. These issues can make the secondary phases of cleft care exceptionally difficult, and as a result many teams try to balance the importance of good speech development with a good growth outcome.

The debate between those who favor early speech development and those who favor optimized growth over the long term has been controversial and heated. Unfortunately, there are few data to settle this argument definitively. Both areas have considerable importance, and practitioners tend to balance these factors based on their own training and individual preferences. The controversy continues, and this state of debate will likely continue for quite some time, given the need to evaluate outcomes over the long term.

Another outcome measure is the presence of a fistula after surgical repair. Many of the same studies mentioned earlier that evaluate speech outcome also report the presence of fistulas after repair. Unfortunately, there is no consistent classification system or accepted method of determining or describing the presence of fistulas. Most of the literature reports a lesser incidence of fistula in the two-flap palatoplasty technique when compared with the Furlow technique, although there are conflicting data. Those surgeons or centers that use the staged cleft palate approach claim that the hard palate opening reduces in size over time after the soft palate has been repaired. This may reduce the occurrence of fistulas when this philosophy is applied, but this concept has not been fully evaluated in the literature in a comparative manner. A change in recent practice is the use of freeze-dried allogeneic dermis as an interpositional graft to augment the cleft palate repair. This has dramatically changed the incidence of fistulas, and the technique is used by some to augment not just revision surgery, but primary surgery as well. When evaluating outcomes, one must consider these variables entirely to compare techniques, study data, and long-term benefits to the patient. The specifics of fistula occurrence after cleft palate repair for each of the approaches is discussed in some detail later.

Other outcomes of interest include the long-term preservation of permanent teeth, occlusion, and maxillary arch form. None of these variables have been comparatively studied in great detail, and little commentary can be made regarding the advantages or disadvantages of particular cleft palate repairs and these particular outcomes. It is not clear if a particular philosophy or technique has proven advantages over another. This is an area that clearly warrants further study.

At present several clinical trials are underway that attempt to address these outcome issues associated with cleft palate repair technique. The statistical power required to make definitive conclusions about which repair technique produces the best outcomes is overwhelming. Consequently, individual surgeon experience and training along with the available pub lished data will have to help shape decisions of the treating surgeon until data are available for critical review.

CHALLENGES OF SPEECH EVALUATION

Many argue that speech outcome is the most important outcome of cleft repair. Although most agree that this is true, few agree on how to measure success in speech. Currently no accepted method of speech evaluation is used to allow for clear comparison among centers. This makes outcome study difficult. Most of the published data to date are retrospective, self-reported, and self-evaluated, which results in significant bias. Exclusion criteria are not consistent across studies and are difficult to determine in this population. For example, whether or not a patient has a syndrome is not always clear, although most studies exclude patients with syndromes or the appearance of a syndrome even if it cannot be identified.

The most concerning and prevalent speech issue in patients with cleft palate is velopharyngeal insufficiency (VPI), often manifested as hypernasal speech with an incompetent mechanism. The incidence of VPI after cleft repair in the literature is impressive in its variability at 0-60%. Because good speech is entirely subjective, it is particularly difficult to have valid and repeatable measuring instruments for use in research. Whenever one evaluates the literature regarding cleft speech outcome, a number of questions must be asked regarding each study:

- •

Who rates the speech in the study?

- •

How is the speech measured, and how subjectively?

- •

Are objective instruments used for measurement and confirmation of a diagnosis, and can they produce a consistent result across the population?

- •

How many evaluators perform the evaluations, and what is the calculated interrater and intrarater reliability?

A number of these issues have been addressed eloquently by Annette Lohmander and her colleagues. Even in the setting in which regular validation mechanisms are used for different speech pathologists within the same center and subscribing to the same philosophies of cleft care and speech, it was noted that interrater and intrarater reliability was much less than expected. It is easy to conclude that data not validated in this manner or data from different centers that use different measures cannot be compared in a meaningful way. Therefore comparing one study with another without validating the measuring tools renders the simple comparison meaningless from a statistical standpoint. Consequently, meaningful metaanalysis of the multiple variables of cleft speech becomes impossible. It should be noted that although objective measures (such as nasometry) exist, they have not been consistently validated owing to their poor predictive value among a population of patients with clefts. Add to these the concepts that speech often changes over the long term, and one quickly realizes how complex the global outcome of “good” speech is to measure. Given these challenges, it is apparent that there is no statistically compelling evidence that one type of cleft repair is better than another.

TIMING OF REPAIR

The timing of cleft palate repair is also filled with controversy. Generally the velum must be closed before the development of speech sounds that require an intact palate. On average this level of speech production is observed by about 18 months of age in the normally developing child. If the repair is completed after this time, compensatory speech articulations may result. Repair completed before this time allows for the intact velum to close effectively, appropriately separating the nasopharynx from the oropharynx during certain speech sounds.

In patients with cleft palate, concerns about normal speech development are frequently balanced with the known biologic consequences of surgery during infancy—namely, the problem of surgery during the growth phase resulting in maxillary growth restriction. When repair of the palate is performed on a patient between 9 and 18 months of age, the incidence of associated growth restriction affecting the maxillary development is approximately 25%. If repair is carried out on a patient younger than 9 months of age, then severe growth restriction requiring future orthognathic surgery is seen with greater frequency. At the same time, proceeding with palatoplasty before 9 months of age is not associated with any increased benefit in terms of speech development, so the result is an increase in growth-related problems with an absence of any functional benefit. Using only the chronologic age, it seems that carrying out the operation during the 9- to 14-month timeline best balances the need to address functional concerns such as speech development with the potential negative impact on growth. To date, no casecontrolled rigorous clinical trial has examined what is likely the most critical factor in dictating the exact timing of cleft repair—the individual child’s true language age.

As mentioned earlier, the concept of staged cleft palate repair addresses the timing and growth issues by delaying the hard palate repair until some point after the velum has been repaired. Even those who advocate this approach admit that there is considerable variation in timing of the soft and hard palate closures performed in different centers. However, in concept the velum is repaired relatively early (perhaps at 6 months), and the hard palate closure is delayed until some point later (perhaps at 2 to 5 years of age). Those who disagree with this approach point out the resultant hypernasal speech caused by nasal air escape through the unrepaired hard palate. Those who favor this approach argue that the long-term speech results are at least equivalent to those of approaches using a single-stage closure technique, and the growth results are markedly better. Therefore according to its proponents there is considerable benefit in applying this philosophy. A comparative study has yet to be performed to the extent that definitive advantages or disadvantages are clearly documented.

PALATOPLASTY TECHNIQUE

Probably the area of greatest controversy is the surgeon’s choice of cleft palate repair technique. The ideal objectives of palatoplasty are (1) closure of oronasal communication from incisive foramen to uvula; (2) creation of a dynamic soft palate that functions well for speech; and (3) performing this without undue consequences to growth. Surgery must not simply be aimed at closing the palatal defect, but rather at the release of abnormal muscle insertions. Muscle continuity with correct orientation should be established so that the velum may serve as a dynamic structure. The manner by which the surgeon accomplishes these objectives is controversial because the relative importance of the previously stated objectives is weighted differently by different clinicians. If one prefers an approach that favors earlier complete repair in the hope of providing better speech, then midfacial growth will likely suffer. Conversely, if the surgeon prefers to greatly favor growth, and delays hard palate repair until much later, then certain aspects of speech may suffer; at least in the short term. To further fuel the controversy, the concept of what is a good outcome is not easily agreed on.

The primary techniques used include variations on a two-flap palatoplasty or the double-opposing Z-plasty technique. The common two-flap techniques involve transposing two large mucoperiosteal flaps medially and closing the cleft palate defect in layers; the hard palate is closed using nasal mucosa and oral mucosa (two-layered closure), and the soft palate is closed in three distinct layers (oral mucosa, musculature, and nasal mucosa). The von Langenbeck procedure leaves the anterior pedicles attached for blood supply purposes but limits the mobility of the tissue in this region. The Wardill-Kilner pushback technique leaves a large defect anteriorly (particularly in bilateral clefts) to effectively place much of the tissue closer to the velum in an attempt to improve speech results. Other variations on this two-flap theme exist, and many modifications have been described.

Those who favor a double-opposing Z-plasty technique purport to posteriorly displace the musculature in a manner that lengthens the palate and improves muscle approximation. This is done using only a two-layered dissection rather than three distinct layers. However, this is made somewhat complex owing to the four flaps and mirror-imaged Z-plasty required to lengthen the palate. In some ways the technique actually tightens the velum in a manner similar to a pharyngoplasty but in a manner that is exclusively at the soft palate rather than the pharynx. The use of dermal grafts has improved the fistula rate, which was previously believed to be higher when using the Furlow technique. This essentially eliminates one of the major drawbacks of the Furlow repair.

An ongoing study from the University of Florida and Sao Paolo, Brazil seeks to evaluate the differences in outcome between the Furlow and von Langenbeck procedures using four surgeons, standardized speech evaluations, a long-term follow-up (approximately 10 years), and enough patients to satisfy a power analysis with the variables at hand. The study remains unpublished in its full form at this time, but preliminary data suggest that many of the variables studied showed no difference in outcome, with the exceptions that the fistula rate is higher in the Furlow group and the hypernasal quality of speech is higher in the von Langenbeck group. It is hoped that additional data will be forthcoming to determine which subset of patients may benefit from which interventions, techniques, and philosophies.

We use a combination of these techniques, customizing the repairs for each patient in a manner that we hope provides the best outcomes in given circumstances. In general, it is recommended that each surgeon use a repair with which he or she is most familiar technically, so as to provide the most consistent results using techniques with which he or she is comfortable.

INTRAVELAR VELOPLASTY

Another controversial aspect of palate repair is the manner in which the musculature of the velum is repaired. How one defines an intravelar veloplasty (IVV) is quite variable; most surgeons consider this process to encompass the aggressive repositioning of the muscle bundles of the soft palate toward the midline and posterior when compared with their original positions. The two-flap palatoplasty and double-opposing Z-plasty techniques address the musculature differently in that a separate dissection of the musculature from the mucosa flaps is not required for the Z-plasty technique. Considerable variability exists among surgeons who perform these techniques. Some surgeons release the tensor veli palatini, whereas others do not. Some surgeons enter the space of Ernst and sweep the levator medially off of the lateral bony boundaries, whereas others do not. Some surgeons osteotomize the vasculature out of the palatine foramen or fracture the hamulus for additional mobilization, but others do not. Some surgeons use septal flaps, but others do not. There are seemingly endless combinations of these variations, and as a result it is very difficult to compare outcomes among different surgeons and techniques.

Although the Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty technique does not have a formal dissection of the levator palatini as some may perform with a two-flap palatoplasty, some surgeons perform the Furlow by releasing the tensor veli palatini from the hamulus and effectively retropositioning the levator and palatopharyngeus musculature in a manner very similar to an aggressive intravelar veloplasty; this is done without dissecting the musculature off of the adjoining mucosal flap. As a result, the Furlow is in some ways technically easier than a three-layered dissection. The question of the muscle apposition being improved when compared with two-flap techniques—with or without intravelar veloplasty—is not resolved in the literature.

The concept of the IVV yielding improved outcomes with respect to closure of the velum and speech quality is one that is often assumed by many cleft palate surgeons. However, little comparative literature exists that definitively proves this concept. Marsh and colleagues prospectively studied the differences in speech outcome (the presence or absence of VPI) after patients had their palatal clefts repaired with or without an intravelar veloplasty. They could find no significant differences between the cohorts of patients and therefore concluded that intravelar veloplasty had no measurable improved outcome. Sommerlad has reported his experience using a particular version of IVV and published improved outcomes with his technique, but no comparative study has been performed in a prospective manner to definitively conclude that this technique is superior to another.

FISTULAS

A fistula after cleft palate repair is defined as a circumferential opening posterior to the incise foramen in the area of intended repair. Fistulas may affect speech if they are large enough but must be fairly sizeable for this to occur. Depending on the location, the fistula often must be larger than 3 to 5 mm in order for it to be symptomatic and affect speech. Large fistulas also may cause nasal regurgitation of foodstuffs. Consequently, only if there is a functional consequence is it prudent to consider closure at an early age. Early surgery to close fistulas that are not problematic puts the patient at needless operative risk and also increases the chances that early surgery would affect midfacial growth in a negative fashion.

Factors that can affect the development of a fistula include type of cleft, width of the original deformity, repair technique, syndrome diagnosis, surgeon experience, patient healing capability or other patient factors, and addition of allograft material or other barrier grafts to augment the closure. Certain types of clefts may be associated with a higher fistula rate when compared with others. For example, the isolated cleft palate is associated with a higher fistula rate than the unilateral cleft palate because of the attachment of the septum to one side of the palatal shelves. This may be compounded by the fact that many patients who have an isolated cleft palate also have a syndromic diagnosis. Patients who have syndromes may have a variety of healing, behavioral, and anatomic factors that affect the overall outcome as well as a fistula rate. Bilateral clefts are reported to have a higher fistula rate when compared with unilateral cleft palate. Wider clefts are technically more difficult to close and therefore have a higher fistula rate. The majority of the literature indicates that the double-opposing Z-plasty technique has a higher fistula rate when compared with most two-flap techniques.

Surgeon experience has been correlated with better outcomes in a number of studies, which emphasizes the importance of regular access to patients with clefts for surgeons who perform these repairs. The addition of allogeneic dermal grafts to the closure has dramatically decreased the fistula rates reported in the literature to very low levels. The long-term effects of the material have not been evaluated in patients with clefts, but use of the material for many other indications has provided good outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important to recognize that a critical review of the literature still does not provide clear answers to the important questions regarding comparative outcome results for cleft palate repair. In the following sections, the concepts of different repair techniques and philosophies are outlined to provide the reader with a broad-based understanding of these concepts. The surgeon today should choose treatments based on the available data, individual philosophy guided by the literature, and experience with the procedure(s). With all aspects of surgery, it is important to avoid unproven methods and to consider the presence or absence of long-term outcome results. The balance between speech and growth outcome is important to consider, no matter which is more important to individual practitioners. Ignoring one or the other surely results in poor outcomes over the long term. Future outcome studies should help determine which aspects of these repair techniques and philosophies are the most helpful for our patients and their long-term outcomes.

Two-Flap Palatoplasty for Cleft Repair

- Sean P. Edwards Bernard J. Costello

While surgeons seek to evaluate the merits of different operative approaches to the management of a cleft palate, the astute practitioner must not forget how these procedures fit into the bigger picture of care for the patient with a cleft deformity. Outcome measures quantifying speech outcomes and fistula rates evaluate clinically relevant but truly surrogate outcome measures for these children. The truest outcome measure would valuate the benefit gained for the patient’s quality of life and compare it with the burden imposed on the patient.

Regardless of the technique employed, the goals of cleft palatoplasty remain the same:

- 1.

Closure of the palate, functionally separating the oral and nasal cavities

- 2.

Development of normal speech with velopharyngeal competence and the absence of compensatory misarticulations

- 3.

Normal facial development

- 4.

Normal occlusal development

- 5.

Normal nasal and nasopharyngeal airway patency

Cleft palate repair, like so many things in surgery, is nuanced. A procedure of a given name is not necessarily the same operation in a different surgeon’s hands. There may be differences in timing of the operation, whether it is staged or not, the extent of dissection, the use or avoidance of vomerine mucosa, how far anteriorly the repair is taken, liberal or conservative use of relaxing incisions, management of dead space with alloplasts or autogenous tissue, and so on. As a result, the reader and surgeon must always be wary of these potential confounders when evaluating the literature for a given technique.

HISTORY

Advances in palate repair have resulted from advances in anesthetic care, permitting earlier repairs, understanding of the anatomy of the palate and the consequences of its aberrancy, increased understanding of growth and development of the craniomaxillofacial skeleton, and the nefarious effects of surgery on the process. The first cleft palate repair has been attributed to a French dentist, Le Monnier, in Rouen in 1764. This repair and many that followed consisted of little more than cauterization of the wound edges, followed by their apposition. Although simplistic by today’s standards, these were bold advances in surgery of the day.

PRINCIPLE TECHNIQUES

Palatoplasty techniques have undergone many innovations in the 150 years since Le Monnier. Variations in these techniques have been aimed at adding length to the soft palate to reduce the incidence of VPI, reducing the incidence of fistula formation, decreasing the adverse effects on midfacial growth, and, in the most recent decades, accomplishing a functional muscular reconstruction of the soft palate to maximize its potential in terms of achieving normal velopharyngeal function.

In essence, palate repair techniques can be described in terms of management of the hard palate or techniques for dealing with the soft palate.

The principle variations on the two-flap palatoplasties, as they are now commonly referenced, are the Veau-Wardill-Kilner pushback, the von Langenback, and the Bardach two-flap palatoplasty. These names refer only to the handling of the mucosa of the hard and soft palate alone, and great variation can be accomplished within each. Repair of the nasal lining is similar for each, with undermining and advancement. Flaps of vomerine mucosa are often elevated, reducing tension on the nasal side closure. In addition, by shifting the suture line to the side so as to not have it aligned with that of the oral side, the potential for fistula formation is reduced. Concern has arisen about the consequences of the use of vomerine mucosa on midfacial growth.

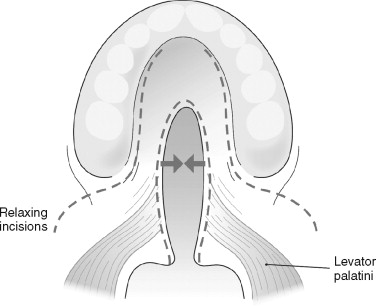

The von Langenback palatoplasty ( Figure 37-1 ) involves the creation of two bipedicled, oral side, mucoperiosteal flaps with lateral releases that can then be mobilized medially for a tension-free repair. These flaps were historically combined with routine ligation of the greater palatine pedicle to further ease medial mobilization of the flaps. The technique is favorable but offers no mechanism to lengthen the velum and may impair access and visibility for repair of the nasal lining at its most anterior extent. Some have also criticized the procedure for limiting access to the cleft velar musculature for its reconstruction. This technique tends not to leave large areas of denuded bone laterally as length is gained on the oral flaps, as they not only translate medially but also reduce the height of the palatal vault.

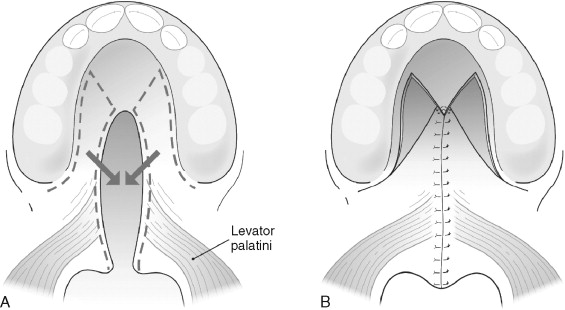

The Veau-Wardill-Kilner palatoplasty ( Figure 37-2 ) epitomizes efforts to gain length in the cleft soft palate. Mucoperiosteal flaps are raised, axially pedicled on the greater palatine vessels, and then mobilized and retropositioned in V-Y fashion to “push back” the oral side flaps and lengthen the velum. This will necessarily leave portions of the anterior hard palate and alveolus denuded and leave a larger alveolar and anterior palatal cleft to deal with at a later date. This denuded bone heals by secondary intention and has been implicated in greater degrees of midfacial growth restriction. Furthermore, the potential exists for large anterior fistulas to affect speech development negatively, owing to the fact that the child will not be able to generate anterior oral air pressure.

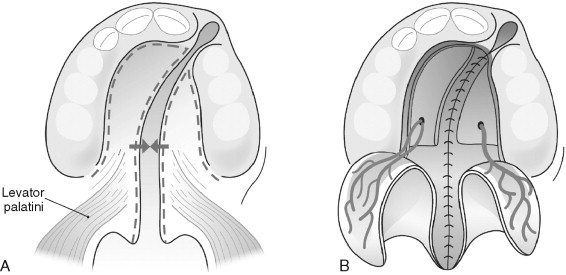

The Bardach two-flap palatoplasty ( Figure 37-3 ) involves the creation of two axially patterned mucoperiosteal flaps pedicled on the greater palatine neurovascular bundles. Access and visibility for the nasal repair and velar muscular reconstruction are excellent. Once the nasal layer and muscular reconstruction are complete, the flaps are medialized and annealed in the midline. Similar to the von Langenbeck technique, large areas of denuded bone are generally not created except in very wide clefts owing to the length gain from rotating the flaps down at the expense of palatal vault depth.

OUTCOMES

FISTULA RATES

Residual fistulas can be problematic on several fronts. They may lead to problems with regurgitation of liquids, which can serve as a source of embarrassment for the young child. Regurgitation of saliva and foodstuff results in chronic nasal and oral mucosal irritation. These fistulas, especially those in the labial vestibule, tend to be quite tender to palpation. They may result in inappropriate nasal air emission, hypernasal resonance, and compensatory misarticulations. When symptomatic, fistulas will require a second operation for their repair.

One should be very careful in the clinical definition of a fistula when referencing the cleft population. It is most appropriate to define a fistula as a persistent opening between the nasal and oral cavities that was intended to be closed —that is to say, a complication, or, as defined by Cohen and colleagues, a failure of healing or a breakdown of the primary surgical repair. A communication in the region of the alveolus after primary palatoplasty is intentionally residual cleft and not a fistula. This differentiation is an important distinction to make when comparing outcomes.

A wide range of aggregate fistula rates with two-flap primary palatoplasties have been reported with cleft palate repairs, ranging from near 0 to 70%. In general, Veau score ( Table 37-1 ) tends to correlate with rates of fistula formation. More severe clefts tend to show greater fistula rates.

| Veau Classification | Extent of Cleft |

|---|---|

| I | Soft palate alone |

| II | Hard and soft palates |

| III | Unilateral complete cleft of the lip and palate |

| IV | Bilateral complete cleft of the lip and palate |

Muzaffar and colleagues, in their review, encountered an 8.7% fistula rate, with all occurring in Veau III and IV cleft palates. Cohen and co-workers, in their comprehensive, multivariate analysis of cleft palate fistulas, had similar results, although a higher overall fistula rate of 23%. Only 4% of the fistulas occurred in the Veau I and II palates, with none occurring in Veau I palates. The remaining fistulas were divided between Veau III, 43%, and Veau IV, 32%, cleft palates.

Age at time of repair seems to correlate with risk of fistula development, although this has not been a consistent finding. Emory and colleagues reviewed palatal fistula formation, and it was noted that the child’s age at time of repair was associated with the incidence of fistulas. The fistula rate was 8% in those undergoing repair before 12 months of age and 19% in those 12 to 25 months of age. Rohrich and colleagues echoed these results, finding a 5% fistula rate in those undergoing palate repair at an average of 10.8 months versus a 35% rate of fistula formation in the late repair group (average of 48 months).

Formation of palatal flaps in such a fashion to accomplish a tension-free repair was the original driving force for innovation in cleft palatoplasty. The two-flap palatoplasty does this very nicely. However, relatively few data exist directly comparing the techniques and their fistula rates. Cohen and colleagues compared the outcomes of Veau-Wardill-Kilner (VWK), von Langenbeck (VL), Furlow, and Dorrance techniques. The Dorrance palatoplasty is a modification of the von Langenbeck procedure with greater medialization of the bipedicled flaps to gain length at the velum. The rates encountered were 43%, 22%, 10%, and 0% respectively. Opposing these findings, Emory and co-workers did not find any significant difference between the two-flap and VWK repairs.

Children who exhibit syndromes have long been held to have higher overall complication rates in a number of areas. This concept has been documented with all types of palatal repair techniques. In some instances the two-flap technique may have advantages over other techniques for these types of patients. This was documented by Bresnick and colleagues in their analysis of children with Treacher Collins syndrome undergoing modified Furlow palatoplasties over a 13-year period. In this study, fistula rates were 4.1% in the nonsyndromic group, 8.7% in the syndromic group, and 50% in the Treacher Collins syndrome cohort.

Surgeon skill, experience, and operative volume have long been perceived as important for good outcomes in many types of surgical procedures. Centralization of care in high-volume surgical units to enhance the quality of care provided and the educational experience for trainees was a core recommendation of the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (Study) in the United Kingdom as a result of a nationwide review of cleft surgery outcomes. Skill is an intangible factor that is hard to evaluate. Emory and colleagues in their review of fistulas after palate repair had the opportunity to compare the outcomes of nine different surgeons within their institution. One surgeon had performed 68% of the repairs, with the other eight being responsible for less than 8% each. They combined these individual surgeon outcomes and compared their fistula rate to that of the high-volume operator. A significant difference was demonstrated, with a 6.5% fistula rate for the high-volume surgeon compared with a 22.2% rate for the grouped, low-volume surgeons. In the review by Cohen and colleagues, they compared the results of individual surgeons, including one who routinely had significant resident surgeon involvement. The surgeon with the highest fistula rate, 63%, had the lowest operative volume over the course of the study, performing only 15% of the 129 repairs. The remaining three surgeons, including the one with trainees, had comparable fistula rates of 14-18%, highlighting the importance of volume in determining outcomes. The difficulty comes in determining where this threshold occurs.

In the end, the two-flap procedures are safe procedures that can be reliably performed with low rates of fistula development. In some instances the two-flap palatoplasty may be preferable to other types of palatal closure techniques (e.g., syndromic diagnoses).

SPEECH OUTCOMES

The development of normal speech is a key outcome measure in cleft palate repair. Normal speech is a crucial component to an individual’s self-esteem and ability to communicate, thrive socially, and be successfully employed. The principal speech disorders associated with cleft lip and palate include abnormal consonant production, abnormal nasality, nasal air emission, nasal turbulence, and poor speech quality.

Speech assessments in the cleft lip and palate population are extraordinarily nuanced. Marsh and colleagues demonstrated that in their cohort an IVV had no effect on later need for pharyngoplasty. How do we rectify these results against those of Sommerlad, who used an IVV to treat velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD) in children who had already undergone palate repair? His muscular reconstruction was successful, with 82% of his cohort achieving normal nasality and airflow, or mild and inconsistent hypernasality, nasal air emission, and turbulence. What is different about these procedures? Are the patient populations that different? Is one surgeon more skilled than another, or are the speech evaluations fundamentally different? More than likely, this is indicative of the differences in methodology and assessment techniques and points to the need for increasing standardization of assessment tools and prospective, multicenter trials.

What should be considered our goal speech outcome in this patient population? This is a question perhaps best answered with each patient individually. Although hoped for, it seems highly unlikely that we will be able to achieve perfect speech for all of our patients, and instead our goals should be tailored to the patient, his or her potential, and, perhaps most important, the patient’s desires.

Speech outcomes with various palate repair techniques are affected by far more than the technique itself. Key components to the development of normal speech include normal cognitive function, normal neuromuscular control and mobility of the velopharyngeal structures, normal occlusion, normal tongue mobility and strength, a patent nasal airway, no fistulas, and normal hearing. Furthermore, there are factors within given patient populations that should be controlled when evaluating a given palatoplasty technique. In general, syndromic children (especially those with velocardiofacial syndrome) will have poorer speech outcomes ( Box 37-1 ).

- •

Age at time of palate repair

- •

Syndromic diagnosis

- •

Cognitive function

- •

Neuromuscular control of velopharyngeal structures

- •

Pharyngeal depth

- •

Oral-motor function

- •

Hearing

- •

Occlusion

- •

Intact dentition

- •

Adenoid and tonsil tissue

The surgeon must also remember that VPD is not a disorder a patient simply has or does not have. Rather, velopharyngeal function and dysfunction exist as a spectrum of competency. Furthermore, mixed patterns of hypernasality and hyponasality occur regularly. This spectrum can be objectively recorded using pressure flow measurements, scoring instruments such as the Pittsburgh Weighted Speech Score and the Cleft Audit Protocol for Speech (CAPS), nasometry, and videofluoroscopy. Getting measurements that are equivalent among centers, those of differing philosophies, or even individual speech pathologists is considerably difficult. When used as a tool to evaluate a single child’s particular situation and his or her progress, subjective speech evaluations and their “objective” measures can be very helpful in directing various therapies.

Fiberoptic nasoendoscopy, although a powerful component of the instrumental speech assessment, should be viewed as a qualitative and not a quantitative study. The clinician should also recognize that speech outcomes are dynamic with respect to age. Park and colleagues found that between ages 4 and 10 years some children improved and others worsened. A child with hypertrophic adenoids at a younger age may experience a decline in velopharyngeal function as the adenoid tissue involutes. This dynamism is supported by Sommerlad, who had patients undergoing secondary velopharyngeal surgery as late as 20 to 25 years after palate repair. Witt and co-workers reviewed speech data in 28 patients examined at 6 years of age and again at 12 years. Overall, 28% of children improved their speech classification, 43% remained unchanged, and 28% deteriorated in their assessment. That said, only 11% deteriorated to the point that surgical or prosthetic management was indicated.

The reader should be cautioned about the use of pharyngoplasty as an outcome measure. This is the most commonly reviewed outcome measure vis-à-vis speech outcomes from palatoplasty. There is a great deal of variation in how a degree of VPD is described and the degree of dysfunction required before operative management is recommended. Furthermore, occasionally there are patient issues in terms of acceptance of a surgical solution, and therefore pharyngoplasty rates would tend to underestimate palatoplasty outcomes. That said, this can be a tangible outcome from both the clinician’s and the patient’s perspectives.

TIMING OF PALATE REPAIR

Because the development of normal speech is an integrated and hierarchical process, it stands to reason that earlier palate repairs are more likely to result in normal speech with fewer compensatory misarticulations. This is because they provide normal anatomy for the child to use while learning how to speak and obviate the need to rely on compensatory misarticulations. These misarticulations are obligatory as the child strives to make the sounds necessary for communication when the palate is not repaired or does not function as intended. In general, most palate repairs are accomplished between 9 and 18 months of age to provide the child with the requisite anatomy for this developmental process.

Kaplan recommended palate repair at 3 to 6 months of age with a goal of normal palatal function by 9 to 12 months of age when palate-related sounds are being learned. Dorf and Curtin, in a relatively uncontrolled retrospective review, evaluated for the presence of compensatory misarticulations in two groups of children. One group, dubbed the early repair group, underwent palatoplasty before 12 months of age, and a late group underwent palatoplasty after 12 months. In the early group, only 10% of children developed compensatory patterns, whereas misarticulations were present in 86% of the children undergoing late repair.

Further evidence of the detrimental effect of delaying palate repair can be gleaned from the speech outcomes of two-stage palatal repairs. In essence, the timing of palatoplasty can be seen as a compromise between maxillary growth attenuation and speech outcomes. Early repairs favor better speech outcomes but are associated with worse facial growth. In an effort to mitigate the effects on growth, surgeons such as Schweckendiek in 1944 proposed early closure of the velum with delayed hard palate closure months to years later. It was felt that velar repair with selective obturation of hard palate defects would provide for normal speech development while avoiding scarring on the hard palate, felt to negatively affect growth. This approach has been validated to provide for superior growth and occlusal outcomes. Several studies have now confirmed the detrimental effects on speech development. In particular, high rates of VPI and compensatory misarticulations are observed. Bardach and colleagues visited the unit of Wolfram, son of Hermann Schweckendiek, in Marburg and documented these poor outcomes. As a result, the two-stage approach, still common in Europe, is rare in North American units.

MUSCULAR RECONSTRUCTION

In an effort to maximize the function of the soft palate, early efforts were directed solely at lengthening the velum. Veau in 1931 first referenced the abnormal muscular anatomy of the velum, referring to it as the “cleft muscle.” Kriens in 1969 published a new approach to veloplasty focusing on a functional reconstruction of the abnormally oriented and divided muscular elements of the soft palate. This procedure, IVV, involves a dissection of the levator veli palatini and palatopharyngeus, detaching it from its abnormal insertion at the posterior edge of the hard palate, retropositioning the bundles while simultaneously reorienting them from a sagittal to transverse position. Despite the obvious logic in the procedure, its value has been questioned by some. Furthermore, some worry that the procedure, by devascularizing the mucosal halves, will lead to a higher rate of fistula development.

Marsh and co-workers conducted a prospective evaluation of the IVV in terms of speech outcomes at 3 years of age. Infants were alternately assigned to either the IVV or non-IVV group as a component of a unipedicled two-flap palatoplasty with no effort at lengthening. The researchers found no appreciable difference in VPD between the two groups. In support of these findings, Hassan and Askar found only a nonsignificant trend toward lower VPD rates when palatoplasty included an IVV. They did find an increased risk of fistula formation in the IVV group.

In contrast to these findings, many studies document excellent speech results when a muscular reconstruction is accomplished by any of a variety of methods. Bitter and colleagues reviewed the speech outcomes of their unit’s operations, all of which included an IVV. Although they had no control group for comparison, they were able to achieve a low rate of pharyngoplasty of 3%. As previously mentioned, this is an area where variations in describing VPI and determining thresholds for what constitutes significant VPI come into play. Muscular reconstruction almost certainly has a positive effect on palate function and its speech development if we look further at the benefit of palatal muscular reconstruction on speech, whether accomplished as a rerepair or as part of a Z-plasty palatal lengthening.

SURGEON VOLUME

Experience seems to correlate with speech outcomes. Sommerlad reviewed his outcomes over a 15-year period in terms of need for secondary velopharyngeal procedures. During the first 5-year period, he experienced a 10.2% secondary velopharyngeal surgery rate. During the next two successive 5-year periods this rate was reduced to 4.9% and 4.6%, respectively. Salyer and co-workers reviewed his 20-year experience with the two-flap palatoplasty. He and his collaborators also noted a reduction in the need for secondary velopharyngeal procedures over the two decades. During the first 10 years the rate was 11%, and it decreased to 6.4% during the second decade for an aggregate rate of 8.9%.

TECHNIQUE COMPARISONS

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses