The presence of midface deficiency in the patient with cleft palate remains a challenging clinical problem frequently encountered in the management of this congenital defect. Facial disproportion associated with maxillary hypoplasia in the cleft patient is almost always the direct biologic consequence of prior surgical intervention. The surgical repair of the lip and palate during infancy, although critical for esthetics and speech development, produces scarring that affects subsequent maxillary growth. In addition, the soft-tissue envelope surrounding the midface is violated again in childhood during placement of bone grafts to construct the cleft maxilla. When necessary, additional revisional surgery for secondary repair of palatal fistulas and other related procedures only further insult maxillary growth potential. In addition to growth-related problems, the scarred soft-tissue envelope can also create difficulties at the time of skeletal corrective surgery and with long-term stability after maxillary advancement.

From a historical perspective, patients with midface deficiency secondary to facial clefting were often ignored. If the deficiency was extreme, surgical intervention was offered usually in the form of mandibular setback. This did little to address the underlying skeletal problem and frequently had the potential to negatively affect the posterior airway. Only with the development of new surgical techniques, a better understanding of the biologic principles of revascularization, and improvements in instrumentation has the patient with midface deficiency secondary to facial clefting benefited functionally and esthetically from surgical correction.

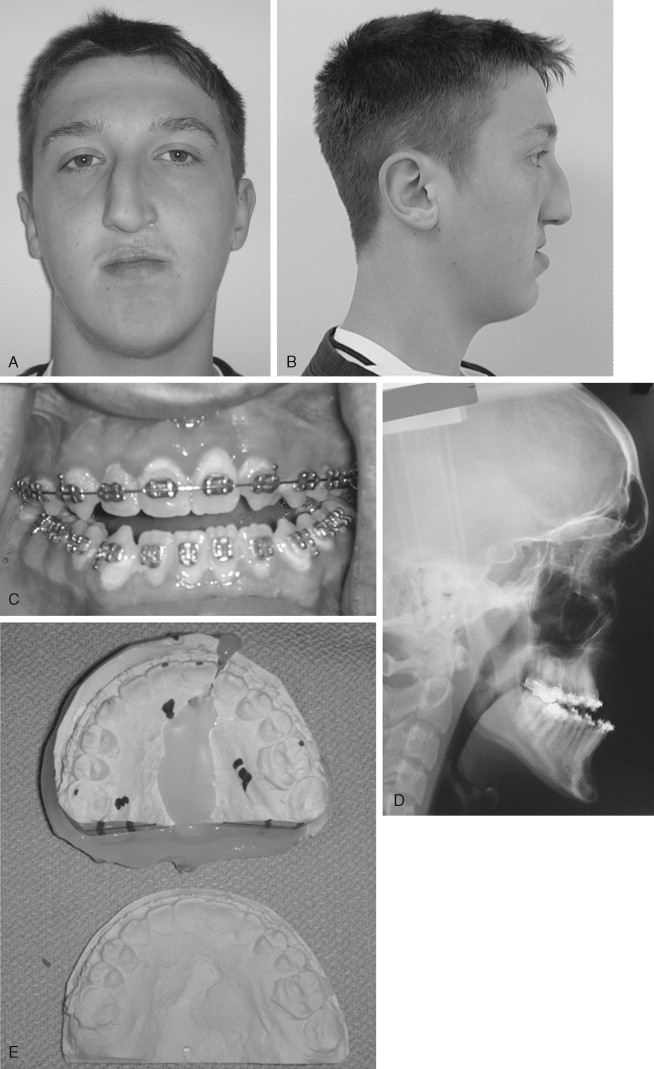

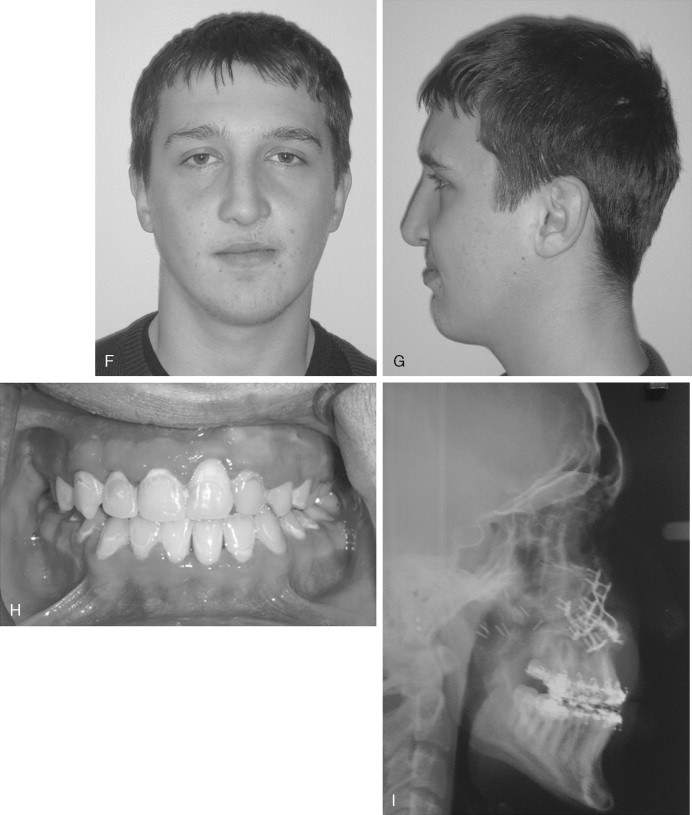

Although midfacial deficiency and class III malocclusion may be the most obvious components of the deformity seen in cleft patients, the dysmorphology is actually more complex. Critical examination of most patients with facial clefts reveals deficiencies of the paranasal, nasal, infraorbital, and maxillary regions. This suggests that the deficiency is not confined to the level of the alveolus and basal bone but extends to involve the entire maxilla and adjacent bones. Understanding that facial clefts involve all tissue layers in the region is critical for effective skeletal surgical planning. The presence or absence of a class III malocclusion has been used in most studies to report the incidence of midface deficiency in cleft lip and palate. Ross estimated that 25% of patients with unilateral facial clefts have a class III malocclusion with a degree of midface deficiency that warrants surgical correction. However, as discussed earlier, more stringent criteria must be applied to correctly determine the presence and severity of midface deficiency in association with cleft lip and palate.

Maxillary deficiency in the presence of facial clefting also results in negative functional consequences on the patient’s speech, nasal respiration, sinus function, olfaction, and hearing. Severe midface deficiency in cleft lip and palate can also contribute to exorbitism and eyelid dysfunction. From an esthetic standpoint, the deformity can also be associated with malar and infraorbital deficiency, lack of nasal tip projection, and deficient upper lip support. The stigmata characteristic of patients with facial clefts are not inherently due to the cleft itself but are caused by the insult of growth potential and surgical scarring in the midface. The result is often both a maxillary deficiency and a maxillary deformity . Therefore, if improvement of esthetic deficits as well as relief of malocclusion are the goals of midface advancement, the surgeon must appropriately address the need for maxillary advancement and bone graft contouring of the deficient facial skeleton for soft-tissue support and reconstruction of structural defects.

PRESURGICAL EVALUATION

The presurgical workup for cleft lip and palate patients follows a path to that of the regular dentofacial deformity population, with a few exceptions. Accurate dental models with a centric bite and facebow transfer, facial and oral photos, facial measurements, and lateral cephalometric and Panorex x-ray films are necessary for both populations. In the cleft patient, obtaining periapical films, an occlusal film, or alternatively a computed tomography (CT) scan that demonstrates the detailed anatomy of the cleft regions and adjacent tissues is helpful. This additional information provides guidance to the surgeon regarding bony anatomy, blood supply, and periodontal status of the adjacent cleft dentition. In addition, information must be gained from the patient’s surgical history regarding previous operations. The surgeon must take into account not only the type of operations, but also what effect a particular type of cleft procedure may have on the current treatment plan. For example, the presence of a pharyngeal flap not only portends issues with intubation during anesthesia, but also informs the surgeon of the potential difficulty that may be encountered with mobilization intraoperatively. Of particular interest to the surgeon is the type of procedure used for palatoplasty. Certain methods of palatal repair (e.g., palatal island flap) can alter the vascular pedicle necessary for the maxilla to survive downfracture and mobilization. The physical examination itself is important and yields information regarding the presence or absence of palatal fistulas and the pattern of scarring in the oral mucosa, lip, and palate. Evaluation of the intranasal anatomy such as the septum and inferior turbinates should also be performed. The septum is usually deflected, and obstructed nasal breathing is a common complaint. Le Fort I osteotomy in most circumstances provides ideal access to these structures when intranasal surgery is indicated.

TIMING OF SURGERY AND PSYCHOSOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Surgical correction of the midface deficiency secondary to facial clefting is ideally performed when the patient is both psychologically and biologically mature to undergo the procedures. As with most patients, surgery to correct midface deficiency in the facial cleft population most prudently occurs after the facial bones have reached skeletal maturity. This improves the predictability of the surgery and decreases the risk of outgrowing the surgical correction. This consideration should always be a component of the informed consent process.

In some instances proceeding with surgery before the completion of facial growth can be considered, especially for those patients with psychosocial comorbidities. Critical to proceeding under these circumstances is the understanding of the patient and parents that additional or repeat surgery may be required once facial skeletal maturation is complete if the patient outgrows the correction. The postoperative course for facial skeletal surgery has become more benign because rigid fixation has eliminated the need for intermaxillary fixation, steroids and antibiotics have controlled swelling and infection, and the use of hypotensive anesthesia and recombinant erythropoietin has dramatically reduced the need for homologous blood transfusion. Despite these advances, the decision to proceed with early surgery should not be taken lightly or be made for the convenience of an impatient surgeon or orthodontist.

Another biologic consideration that affects the timing of surgery is the eruption of the permanent dentition. Delaying surgery until after the eruption of the permanent maxillary canines and second molars minimizes the risk of injury to the teeth during osteotomy. Impacted wisdom teeth (third molars) can be safely removed during the osteotomy, and their presence should not delay surgery. In fact, removing them during the osteotomy reduces the number of surgical procedures the child may undergo.

Improvement of self-concept and self-image in cleft patients almost always follows surgery to address facial skeletal disproportion. This must not be overlooked when considering the timing of surgery. Improving facial balance by surgical correction of disproportion often results in dramatic and favorable changes. The patient and family often perceive these changes positively. In addition, as the procedure is likely the penultimate correction of the cleft deformity, a sense of achievement is usually felt by the patient and family after years of effort directed at multiple dental and surgical procedures. In contrast, a few patients with dependency directed at their facial stigmata may respond differently to surgical treatment. This is difficult to determine preoperatively, and the involvement of a psychologist familiar with children with facial deformities can be invaluable in these instances.

As with any patient with a congenital facial malformation, cleft patients are psychologically different from most patients with acquired facial deformities. The congenital nature of the deformity requires multiple psychologic adjustments with every procedure. Many cleft patients are acquainted with the disappointment after soft-tissue procedures aimed at reducing lip scarring and correcting nasal asymmetry. For still others, unrealistic expectations may accompany corrective skeletal surgery. These patients should be identified early through complete cleft team evaluations and referred for counseling preoperatively.

All children with facial deformities, congenital or acquired, can become victimized because of their facial differences. This may become more prevalent during the adolescent years. Enormous peer pressure is felt at this age, especially in the United States. Adolescents with cleft lip and palate are often ridiculed during this period in their lives, and low self-esteem with social withdrawal can follow. Although counseling can help, the patient must also learn to cope with the problem, which may be improved with corrective skeletal surgery.

TIMING OF SURGERY AND PSYCHOSOCIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Surgical correction of the midface deficiency secondary to facial clefting is ideally performed when the patient is both psychologically and biologically mature to undergo the procedures. As with most patients, surgery to correct midface deficiency in the facial cleft population most prudently occurs after the facial bones have reached skeletal maturity. This improves the predictability of the surgery and decreases the risk of outgrowing the surgical correction. This consideration should always be a component of the informed consent process.

In some instances proceeding with surgery before the completion of facial growth can be considered, especially for those patients with psychosocial comorbidities. Critical to proceeding under these circumstances is the understanding of the patient and parents that additional or repeat surgery may be required once facial skeletal maturation is complete if the patient outgrows the correction. The postoperative course for facial skeletal surgery has become more benign because rigid fixation has eliminated the need for intermaxillary fixation, steroids and antibiotics have controlled swelling and infection, and the use of hypotensive anesthesia and recombinant erythropoietin has dramatically reduced the need for homologous blood transfusion. Despite these advances, the decision to proceed with early surgery should not be taken lightly or be made for the convenience of an impatient surgeon or orthodontist.

Another biologic consideration that affects the timing of surgery is the eruption of the permanent dentition. Delaying surgery until after the eruption of the permanent maxillary canines and second molars minimizes the risk of injury to the teeth during osteotomy. Impacted wisdom teeth (third molars) can be safely removed during the osteotomy, and their presence should not delay surgery. In fact, removing them during the osteotomy reduces the number of surgical procedures the child may undergo.

Improvement of self-concept and self-image in cleft patients almost always follows surgery to address facial skeletal disproportion. This must not be overlooked when considering the timing of surgery. Improving facial balance by surgical correction of disproportion often results in dramatic and favorable changes. The patient and family often perceive these changes positively. In addition, as the procedure is likely the penultimate correction of the cleft deformity, a sense of achievement is usually felt by the patient and family after years of effort directed at multiple dental and surgical procedures. In contrast, a few patients with dependency directed at their facial stigmata may respond differently to surgical treatment. This is difficult to determine preoperatively, and the involvement of a psychologist familiar with children with facial deformities can be invaluable in these instances.

As with any patient with a congenital facial malformation, cleft patients are psychologically different from most patients with acquired facial deformities. The congenital nature of the deformity requires multiple psychologic adjustments with every procedure. Many cleft patients are acquainted with the disappointment after soft-tissue procedures aimed at reducing lip scarring and correcting nasal asymmetry. For still others, unrealistic expectations may accompany corrective skeletal surgery. These patients should be identified early through complete cleft team evaluations and referred for counseling preoperatively.

All children with facial deformities, congenital or acquired, can become victimized because of their facial differences. This may become more prevalent during the adolescent years. Enormous peer pressure is felt at this age, especially in the United States. Adolescents with cleft lip and palate are often ridiculed during this period in their lives, and low self-esteem with social withdrawal can follow. Although counseling can help, the patient must also learn to cope with the problem, which may be improved with corrective skeletal surgery.

SURGICAL RECONSTRUCTION

Surgeons who care for children with cleft lip and palate deformities must proceed with an understanding of the three-dimensional regional anatomy, the extent of hard- and soft-tissue defects present, and the complex interplay between surgery and subsequent maxillofacial growth. This understanding allows the clinician to formulate and sequence appropriately the staged surgical treatment of patients with cleft lip and palate from the initial consultation in infancy through adulthood. The goals of skeletal reconstruction include improvement of skeletal proportion and balance, correction of the occlusion, normalization of nasal breathing, closure of residual defects and fistulas, and improvement of the soft-tissue position by providing a bony foundation for support.

Maxillary advancement in the patient with cleft lip and palate does not remove scarring of the lip or correct anatomic soft-tissue landmarks. It does, however, provide the best opportunity for skeletal foundation support of the soft-tissue drape. Usually an improvement in lip and nasal asymmetry as well as further support for the nasal tip are seen postsurgery. By providing improved structural support, skeletal surgery may reduce the soft-tissue stigma enough to diminish the need or desire for revisional procedures of the lip and nose. Advancement of the skeletal foundation changes the visual perception of the scar by altering the pattern of light reflection, thus making it less obvious. In addition, the common practice of placing the lip scar in the philtral column to diminish its prominence is often counteracted by the underlying deficiency of the maxillary skeletal base. This places the scar on the most flat, unsupported area of the lip, which is far more obvious. Advancement of the skeletal base not only improves the soft-tissue drape but also moves the scar to an area of greater curvature on the lip, making it less conspicuous. Patients should be counseled that midface advancement sets the stage for definitive lip and nasal revisions in the future ( Figure 41-1 ).

The residual skeletal dysmorphologies that can be present in patients with unilateral cleft lip and palate are numerous and often found in combination ( Box 41-1 ). Reconstruction of these defects and deformities requires accurate diagnosis, thoughtful treatment planning, and precise surgical execution of the defined treatment plan. This reconstructive effort typically involves multiple clinicians who have varying degrees of involvement based on the patient’s stage of development and specific esthetic and functional demands.

-

Residual cleft lip and nasal scarring

-

Nasal cartilage distortion

-

Deviated septum

-

Hypertrophied nasal turbinates

-

Unrepaired or residual oronasal fistulas associated with the primary palate (cleft)

-

Cleft dental gap

-

Missing or malformed teeth

-

Dental crowding

-

Complex malocclusion

-

Periodontal disease

-

Inflammation of the soft tissue surrounding oronasal fistulas

-

Defects or hypoplasia involving the pyriform rim, nasal floor, and alveolus

-

Maxillary hypoplasia (anteroposterior, vertical, and transverse)

-

Maxillary canting and asymmetry

-

Compensatory mandibular asymmetry

-

Mandibular growth disturbance

In patients with bilateral cleft lip and palate, similar dysmorphologies are present; however, additional dental and skeletal discrepancies may also be present ( Box 41-2 ). If successful bone grafting of the bilateral cleft maxilla has been performed, with elimination of fistulas, and bony continuity is achieved, then conventional Le Fort I osteotomy may proceed (with or without concomitant mandibular surgery). Despite successful bone graft reconstruction of the bilateral cleft maxilla, segmental surgery can be more complicated because of palatal scarring, incomplete graft consolidation, and lack of an adequate vascular supply to the premaxilla. A thorough preoperative evaluation of the previous procedures and clinical and radiographic examinations is required before midface advancement is undertaken.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses