Body dysmorphic disorder is a psychiatric condition that affects about 2% of the population. The objective of this article was to create awareness among orthodontists of this disorder and offer guidelines for its detection. As clinicians providing cosmetic services, orthodontists are likely to have patients with body dysmorphic disorder requesting treatment.

First described in 1886 and documented by Morselli as dysmorphophobia and eventually recognized as a disorder by the American Psychiatric Association in 1987, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a mental condition that is characterized by a distressing or impairing preoccupation with an imagined or a slight defect in appearance. BDD affects 2% of the general population in the United States and between 6% and 15% of dermatologic and cosmetic surgery patients. Although 1 study reported a preponderance of BDD in women, with a 3-fold incidence of that in men, others found equal distributions between men and women, or a higher incidence in men. With the growing tendency for people to seek cosmetic enhancements, patients with BDD are likely to consult orthodontists for treatment. The percentage of patients with BDD who seek surgery suggests that between 300,000 and 400,000 might request orthodontic treatment once and perhaps several times during their lifetime. Thus, it is vitally important that orthodontists create adequate awareness of this condition and identify its characteristics and symptomatology to allow for referral for diagnosis and appropriate management.

Findings from a recent study showed the types of therapies that persons with BDD seek. In this study, 142 of 200 subjects with BDD (71%) sought and received nonpsychiatric treatment for their “defect.” On average, patients consulted 2.4 providers, for a mean of 9.3 visits. Adolescents with BDD first sought nonpsychiatric treatment at a mean age of 14.8 years (SD, ± 1.5 years; range, 13-17 years). Among the 528 procedures or treatments sought, the most frequently requested were dermatologic ( Table ). Seven of 142 subjects (4.9%) requested orthodontic treatment, and 10 of 142 subjects (7.0%) requested jaw surgery, a procedure that requires adjunct orthodontic treatment.

| Treatment | n |

|---|---|

| Dermatological | 303 |

| Topical acne agents | 118 |

| Oral acne agents | 76 |

| Surgical | 118 |

| Rhinoplasty | 33 |

| Liposuction | 12 |

| Breast augmentation | 11 |

| Dental | 142 |

| Tooth whitening | 11 |

| Jaw surgery | 10 |

| Braces | 7 |

A more recent study reported a 7.5% incidence of BDD in an orthodontic patient sample compared with a 2.9% incidence in a general public sample. This study suggested that a higher percentage of the general population affected with BDD could be seeking orthodontic treatment.

Orthodontists need to be well aware of this condition. A recent editorial by Thompson and Durrani in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine stressed “an increasing need for early detection of body dysmorphic disorder by all specialties.”

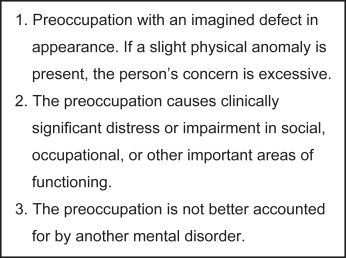

The diagnosis of BDD, or body dysmorphia, dysmorphic syndrome, or dysmorphophobia (as it was previously called), should be established by a psychiatrist. The criteria for diagnosis are listed in Figure 1 . A review of BDD provides insights and indicators of the condition from other specialties. Importantly, BDD remains undetected and undiagnosed in many patients seeking various cosmetic therapies. These people most often complain about imagined or slight flaws in their faces and heads such as acne, wrinkles, scars, vascular markings, swelling, facial asymmetry or disproportion, hair thinning, or excessive facial hair. Other common preoccupations include the shape, size, or another aspect of the head, nose, eyes, eyelids, eyebrows, ears, cheeks, lips, mouth, jaws, and teeth. A major feature of BDD is an obsession with an imagined or greatly exaggerated defect in appearance. As orthodontists, we should be alert for patients extraordinarily concerned about insignificant or negligible dental flaws or defects, such as dental rotations, interdental spacing, misalignment of a midline, tooth-mass discrepancies, and other minimal imperfections. Patients reporting multiple requests for orthodontic treatment or seeking evaluations with several colleagues, either before or after treatment, should raise our suspicions for BDD. Additionally, the person suffering from BDD might focus on other body areas: arms, hands, legs, feet, hips, shoulders, spine, abdomen, genitals, breasts, larger body regions, overall body size, and muscularity. Not uncommonly, concomitant psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, are found in patients with BDD.

Those with BDD who undergo cosmetic therapy typically are dissatisfied with the results. Hodgkinson warned plastic surgeons that these patients are “profoundly dissatisfied with the (surgical) results,” and Cunningham and Feinmann stressed the relevance of BDD in patient satisfaction with orthognatic surgery. A survey of 265 cosmetic surgeons showed that 84% of them had operated on at least 1 patient with BDD. Only 1% of the BDD patients postoperatively reported having their chief complaint satisfactorily addressed. Furthermore, 40% of the surgeons reported that a patient with BDD had threatened them legally or physically.

Additional time for pertinent medical-history recording might be necessary and is frequently useful for the orthodontic clinician when evaluating a patient likely to have BDD. Importantly, a person exhibiting characteristics of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) might have BDD, since the manifestations of the 2 conditions are similar. 4 Questions directed toward specific BDD criteria, as well as for assessing OCD, should be included in the patient’s medical and dental history. The patient’s chief complaint needs to be thoroughly evaluated and a determination made regarding whether it is a real defect or, if extremely slight, minor or insignificant. Two assessment and screening guides for BDD available in the medical literature are recommended as valuable resources.

The consequences or penalties for preliminary screening misdiagnosis of this condition could be high, and we can carry this heavy psychological load for many years. As orthodontic clinicians, we certainly know about “difficult” patients, and, even worse, they are a potential source of legal problems.

In 1978, Marbach reported case histories of orthodontic patients whom he described as psychiatrically affected. According to him, these patients had a condition he dubbed “the phantom bite.” Their reported complaints, requests, and behavior closely resembled the description of the symptoms presented here, and they might have been patients who now could be diagnosed with BDD.

Patients suspected of having BDD should be referred to a psychiatrist for definitive diagnosis and management. Adequate diagnosing of BDD is essential and should be established early before starting orthodontic treatment. Since persons affected with BDD might concomitantly have OCD, or since comorbidity with other potential psychiatric disorders could be present (depression, social phobia, OCD, somatization, and delusional and somatoform disorders, among others), every effort should be made to refer these patients to a psychiatrist, and the orthodontist should not attempt to reach such a diagnosis alone. Further still, some persons might even notice correction of their bodily defect but not acknowledge it or attribute it to their overall satisfaction. The diagnosis of psychiatric conditions is complex.

Treatment of BDD consists of pharmacotherapy and behavioral therapy. Sometimes, performing the orthodontic procedure requested might be an integral part of the patient’s treatment, but this should always be based on the recommendation of the treating psychiatrist.

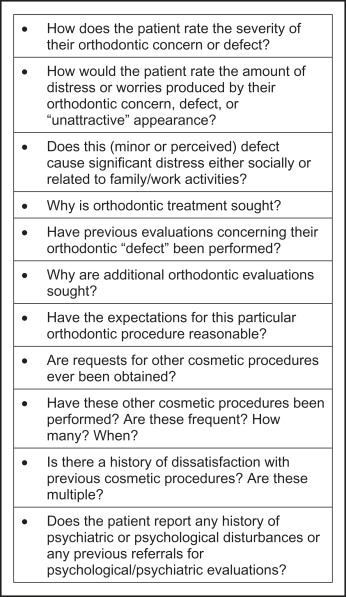

The purpose of this article was to give readers a questionnaire developed by the author for specific use by orthodontists when evaluating possible BDD patients in their practices, based on the above-mentioned criteria and the 2 previously cited guides ( Fig 2 ). I believe that, after familiarizing ourselves with this condition, any patient who might make us suspect BDD should be further assessed. This questionnaire should serve as a tool in their assessment: possible issues or topics that could indirectly and discreetly be introduced in the evaluation and interview of these patients are presented. Actually, having the patient complete, date, and sign a comprehensive medical history form that could include the checking of conditions, previous surgeries, and so on, might prove helpful in assessing potential BDD patients. Timing for asking these questions is of the utmost importance.