Blepharoplasty, commonly referred to as “eyelid lift,” is a widely accepted and performed esthetic surgical procedure. Contributing to its popularity is its relative ease of performance, the fact that it can be done in an office setting with minimal anesthesia, and the lack of a prolonged recovery period. According to a recent survey, blepharoplasty of upper and lower lids was the third most commonly performed cosmetic procedure in the United States in 2005, trailing body liposuction and breast enhancement.

The history of blepharoplasty to correct lid disorders dates all the way back to the first century AD in Rome. Since then, multiple refinements and modifications have been proposed.

Eyes are the “windows to the soul”; attractive eyes are one of the main features of an esthetic and balanced face ( Figure 25-1 ). To achieve an excellent result, blepharoplasty of upper and lower lids demands a clear understanding of the appropriate preoperative diagnosis and regional anatomy, surgical execution, and management of postoperative complications. Perhaps more important than the aforementioned concepts, it is paramount to remember that any cosmetic surgical procedure requires an appreciation of what the patient wants. Discrepancies between what a practitioner wants to treat and what the patient wants to have treated can lead to suboptimal results. Often, a patient presents to the clinician’s office with a specific complaint regarding the appearance of the periorbital region. Given the vast amount of information available on the Internet, most patients can be quite focused about their concerns. Considering the complex anatomy of the periorbital region, the clinician must formulate a clear diagnosis and a treatment plan that corresponds to the patient’s concerns. For example, a patient may not be satisfied with the appearance of the upper eyelids and may complain that she has difficulty applying makeup to the upper lids simply because they are so sagging. This patient may present for what she perceives as an eyelid issue. Often, however, the patient suffers from brow ptosis and may actually need a brow lift to address the sagging eyelids ( Figure 25-2 ). Therefore, proper preoperative communication and treatment planning are absolutely necessary for satisfactory results and a happy patient. The purpose of this chapter is to familiarize the reader with commonly used nomenclature, surgical anatomy, patient selection, surgical execution, and potential complications associated with upper and lower lid blepharoplasty.

NOMENCLATURE

As is common with many esthetic procedures, multiple phrases and terms are used to describe the appearance of the upper and lower lids. This sometimes can lead to confusion for the novice surgeon. A list of commonly used diagnoses follows:

- •

Dermatochalasia: This nonspecific term implies excess skin; it is applicable to any part of the facial skin and typically is due to a weak bony foundation (hypoplastic infraorbital rim in the case of lower lids), the aging process, exposure to sunlight, and environmental causes ( Figure 25-3 ).

FIGURE 25-3 A patient with upper lid dermatochalasia. Note the normal position of the brows. - •

Blepharochalasia: This more specific term suggests an inflammatory component to redundant skin of the lids. This condition often is related to angioedema and episodic swelling and edema of the periorbital region ( Figure 25-4 ).

FIGURE 25-4 A patient with angioedema of the upper and lower lids. This can be referred to as blepharochalasia. - •

Blepharoptosis: This acquired or congenital condition relates to drooping of the upper lids. It usually follows disinsertion of the levator palpebral aponeurosis from the upper tarsal plate ( Figure 25-5 ). This condition is different from brow ptosis, which often causes excess upper lid skin. Blepharoptosis can occur simultaneously with dermatochalasia and blepharochalasia of lids.

FIGURE 25-5 Bilateral upper lid ptosis. Note the location of the upper eyelid in relation to the superior limbus. - •

Prolapsed fat pads: Prominent lower lid fat pads or medial fat pad of the upper lid can present as a “bulge” caused by weakening of the orbital septum. The term prolapsed is more accurate than herniated in that the septum is still intact, albeit weak, as opposed to a herniation, which includes a distinct opening through which fat bulges ( Figure 25-6 ).

FIGURE 25-6 A patient with significant upper lid dermatochalasia, with prolapsed lower lid fat pads and nasal fat pads of the upper lids. - •

Hypertrophic orbicularis oculi: This is a distinct and hypertrophic portion of the pretarsal component of the orbicularis oculi in the lower lid. Although it may be considered an esthetic issue in many individuals, in some patients, this condition may exacerbate the bulge in the lower lid.

- •

Prolapsed lacrimal gland: This infrequent occurrence is due to weakness of the septum of the upper lid, which causes a unilateral or bilateral fullness in the lateral aspect of the upper lids, which may result from descent of the lacrimal gland.

- •

Lower lid malposition: This general term applies to any degree of abnormality associated with the lower lid. This could encompass frank ectropion, entropion, lower lid rounding or shortness, and lateral canthal dystopia ( Figure 25-7 ).

FIGURE 25-7 A patient with significant lower lid laxity. This patient must undergo a lid-tightening procedure in addition to blepharoplasty.

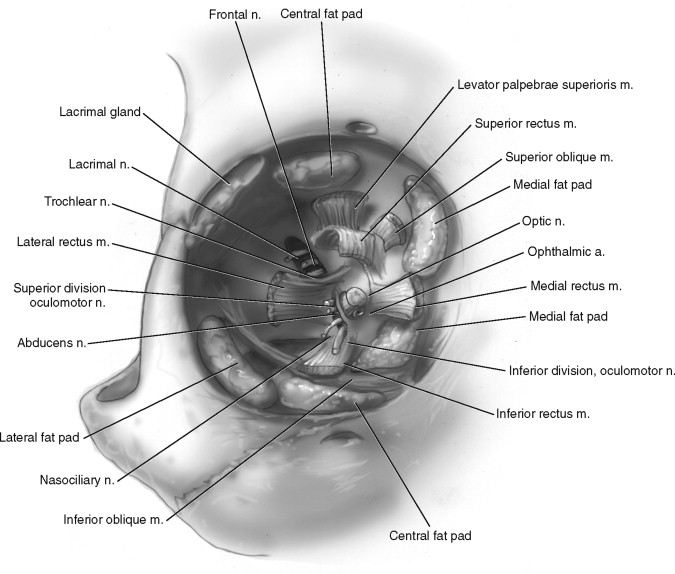

ANATOMY

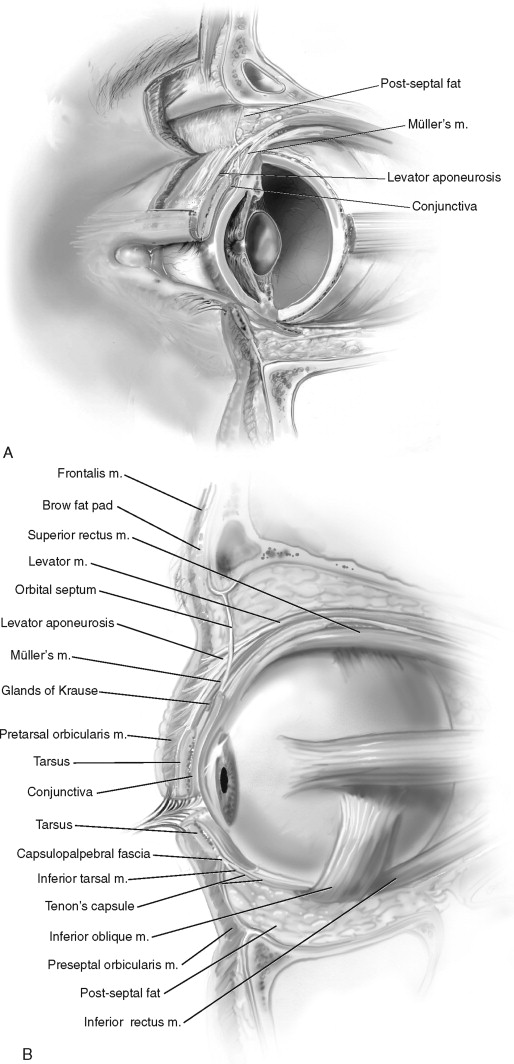

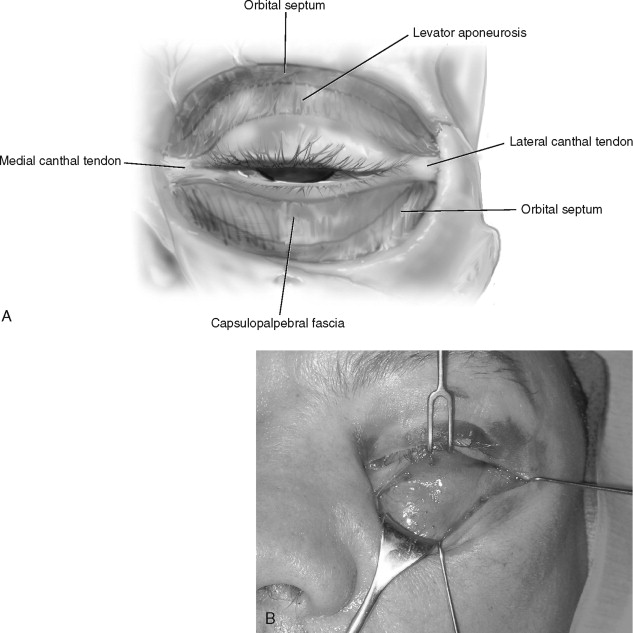

Surgical anatomy of the eyelids is rather complex. Numerous structures are present in the upper and lower lids that have similar functions but different names ( Figure 25-8 ). Also, it is imperative to remember that at times, surgical alterations in lid anatomy may involve alteration of the brow or mid-face structures as well; therefore, an understanding of the surgical anatomy of those particular areas is helpful.

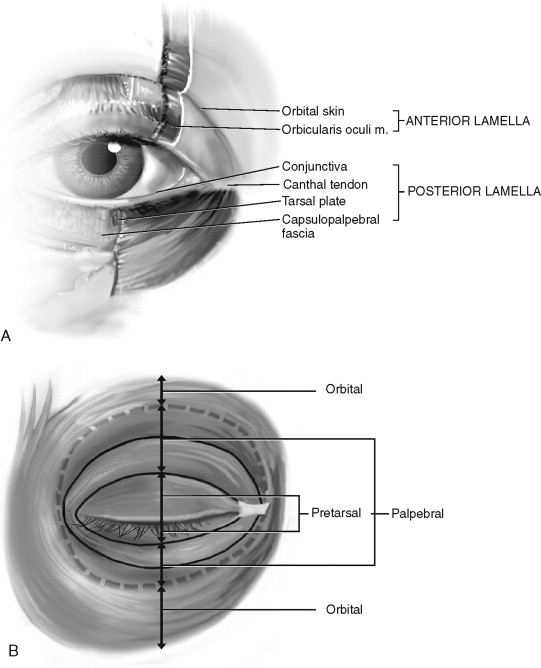

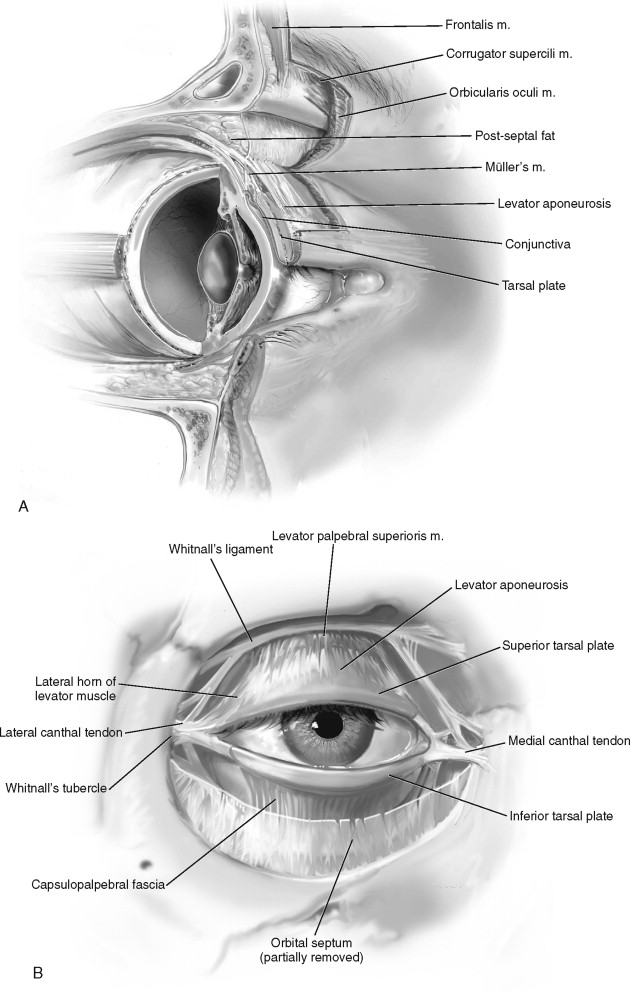

The most consistent way to gain an understanding of the surgical anatomy of the upper and lower lids is to divide each lid into three lamellae: anterior, middle, and posterior. Each lamella has several components that will be discussed individually:

- •

Anterior lamella: Skin, orbicularis oculi

- •

Middle lamella: Orbital septum, orbital fat pads

- •

Posterior lamella: Lid retractors, suspensory system, tarsus, conjunctiva

ANTERIOR LAMELLA

The anterior lamella includes the skin of the eyelid and the orbicularis oculi muscle ( Figure 25-9 ). Upper and lower lid skins represent the thinnest skin on the body; the average thickness of the epidermis complex in the adult lid is about 130 microns. This thinness can be considered both an attribute and a disadvantage for the surgeon; although the lid skin is amenable to massage following surgery if necessary, it is also susceptible to scarring if handled improperly during surgery.

A clinically significant region of the skin of the upper lid is the supratarsal crease. This crease (two distinct creases in many patients) is the point of attachment of the upper septum to the aponeurosis of the levator palpebral superioris muscle. This crease usually is found about 8 to 10 mm cephalad to the upper lid margin. No well-defined creases are noted in the lower lid of most patients; however, with age and exposure to the environment, lower lid creases/rhytids begin to develop just inferior to the lashes. These creases run in a medial to lateral direction and can be used for placement of an incision for a transcutaneous lower lid blepharoplasty.

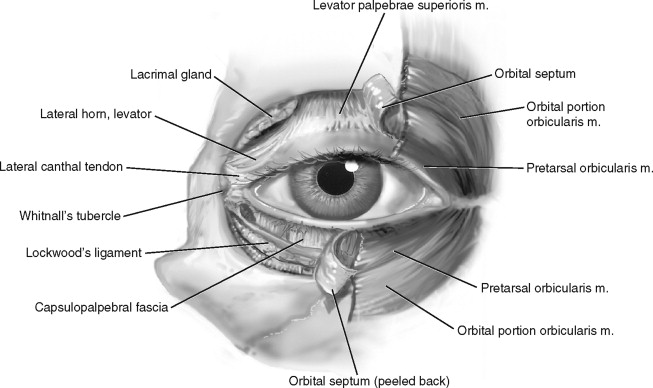

The orbicularis oculi is a circular skeletal muscle that encompasses the lids and adjacent tissues. This muscle is innervated by the facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) and has two major components: palpebral and orbital. The palpebral portion is further subdivided into pretarsal and preseptal portions. The orbital portion originates from the superomedial and inferomedial orbital rim, the maxillary process of the frontal bone, the frontal process of the maxilla, and the medial canthal tendon. The fibers sweep across the eyelids, onto the forehead and the cheek regions, respectively. The orbital portion covers the corrugator supercilii muscle. This portion of the orbicularis oculi is rarely encountered during blepharoplasty. Only involuntary movements are associated with the orbital portion of the muscle.

The preseptal and pretarsal components of the palpebral portion of the muscle have voluntary and involuntary movements. The pretarsal portion is firmly attached to the tarsal plates; the preseptal component is anchored medially to the medial canthal tendon and is attached laterally to the lateral canthal region. The palpebral components of the orbicularis oculi are responsible for the blink reflex and for movement of the marginal tear film toward the lacrimal puncta.

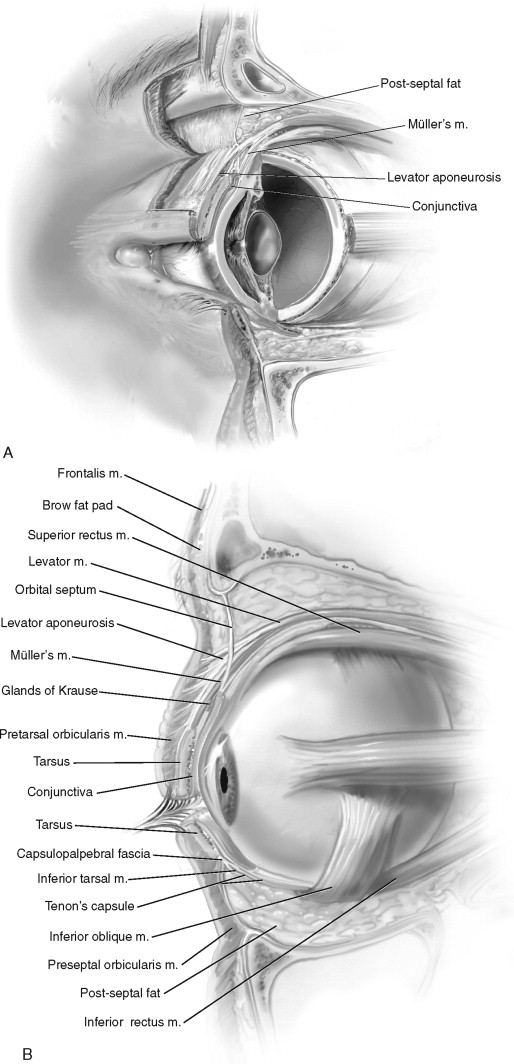

MIDDLE LAMELLA

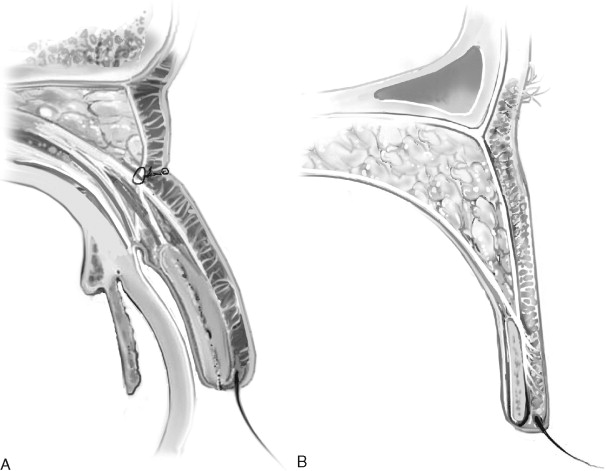

The middle lamella comprises the orbital septum and the orbital fat pads ( Figure 25-10 ). The septum is essentially a fascial membrane that separates the eyelids from the deeper orbital contents. The septum maintains the orbital fat pads on its posterior surface. In both lids, the septum originates from the arcus marginalis , the confluence of the periorbital periosteum and the periosteum of the facial bones. In the upper lid, the septum attaches to the levator aponeurosis, about 2 to 5 mm above the superior edge of the tarsal plate; this fusion represents the clinically significant supratarsal crease. This crease may not be present in approximately 50% of the Asian population. In this group of patients, the septum attaches directly to the superior aspect of the upper tarsus ( Figure 25-11 ). In the lower lid, the septum attaches directly to the inferior aspect of the tarsal plate. The orbital septa of the lower and upper lids actually meet each other medially just deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle around the posterior lacrimal crest. Laterally, the septum fuses with the lateral canthal tendon region.

Just deep to the septum, one finds the preaponeurotic orbital fat pads and the lacrimal gland ( Figure 25-12 ). In the upper lids, two fat pads are found: nasal and middle. The lacrimal gland occupies the space laterally. These two fat pads separate the septum from the underlying levator aponeurosis. The tendon of the superior oblique muscle separates the central fat from the nasal fat compartment. In the lower lids, three fat pads can be identified: medial, central, and temporal. The medial fat pad is the most vascular; this is of clinical significance during fat removal in blepharoplasty if postoperative retrobulbar bleed is to be prevented. The inferior oblique muscle separates the medial from the central fat pad. The temporal fat pad may have more than one component.

POSTERIOR LAMELLA

Lid retractors, the suspensory system, the tarsus, and the conjunctiva make up the posterior lamella of the lids ( Figure 25-13 ). Lid retractors oppose the action of the orbicularis oculi. In the upper lid, the retractors include the levator aponeurosis (fascial condensation of the levator palpebral aponeurosis, LPS) and Müller’s muscle. LPS is a parasympathetically innervated muscle (cranial nerve III) that originates from the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone, travels superior to the superior rectus muscle, and becomes aponeurotic as it attaches to the lower two thirds of the anterior surface of the upper tarsal plate. Müller’s muscle is a sympathetically innervated (superior cervical chain) muscle that originates from the inner surface of the LPS and inserts onto the superior edge of the upper tarsal plate. Both muscles are elevators of the upper lid. In the lower lid, the lid retractors include the capsulopalpebral fascia and a lesser defined muscle known as the inferior tarsal or palpebral muscle, also known as Horner’s muscle. The capsulopalpebral fascia is an extension of the inferior rectus muscle that attaches to the inferior edge of the lower tarsal plate. Horner’s muscle is a portion of the deep head of the orbicularis oculi muscle. These two lower lid retractors are analogous to the levator aponeurosis of the LPS and Müller’s muscle of the upper lid, respectively.

The two hammock-like suspensory systems of the upper and lower lids include Whitnall’s ligament and Lockwood’s ligament, respectively. These also are known as the superior and inferior transverse suspensory ligaments. They protect the globe from cranio-caudal movement. Whitnall’s ligament is a fascial condensation that originates from the trochlea and attaches to the orbital lobe of the lacrimal gland. This ligament is found just superior to the LPS but deep to the septum. Lockwood’s suspensory ligament is a fascial condensation of Tenon’s capsule (bulbar fascia), which runs between the orbital walls and attaches to the lateral retinaculum. Lockwood’s suspensory system is located just anterior to the capsulopalpebral fascia.

Tarsal plates provide the main skeletal support for the upper and lower lids. These are made of dense fibroelastic tissue lined with Meibomian glands. In the lower lid, the tarsal plate is only 5 to 6 mm in height; in the upper lid, the plate is 9 to 11 mm in height.

The conjunctiva makes up the last component of the posterior lamella. It lines the inner-most aspect of the lids (palpebral conjunctiva), forms the fornix, and then turns onto the globe and covers the anterior-most aspect of the cornea (bulbar conjunctiva).

Although they are not specifically components of the posterior lamella, the lateral and medial canthi play a significant role in the transverse and spatial relationships of the lower and upper lids. Lateral and medial canthi are lateral and medial fibrous extensions of the tarsal plates. Both canthi have two heads: superficial and deep (anterior and posterior). The anterior limb of the medial canthus and the posterior limb of the lateral canthus are thicker than their counterparts. The two limbs of the medial canthal tendon cover the lacrimal sac; the two limbs of the lateral canthal tendon cover Eisler’s fat pad.

The lateral retinaculum (LR) is a clinically significant structure in the lateral orbital rim ( Figure 25-14 ). The LR is essentially a labyrinth of connective tissue that is anchored within the lateral orbital rim and maintains the position, integrity, and function of the globe. It is attached to Whitnall’s tubercle, a bony protuberance 10 mm inferior to the zygomatico-frontal suture and 3 mm posterior (deep) to lateral orbital wall rim within the zygomatic bone. The following structures attach to the LR:

- •

Lateral canthal tendon (posterior limb)

- •

Lateral horn of the LPS aponeurosis

- •

Lockwood’s ligament of the lower lid

- •

Check ligament of the lateral rectus muscle

ANATOMY

Surgical anatomy of the eyelids is rather complex. Numerous structures are present in the upper and lower lids that have similar functions but different names ( Figure 25-8 ). Also, it is imperative to remember that at times, surgical alterations in lid anatomy may involve alteration of the brow or mid-face structures as well; therefore, an understanding of the surgical anatomy of those particular areas is helpful.

The most consistent way to gain an understanding of the surgical anatomy of the upper and lower lids is to divide each lid into three lamellae: anterior, middle, and posterior. Each lamella has several components that will be discussed individually:

- •

Anterior lamella: Skin, orbicularis oculi

- •

Middle lamella: Orbital septum, orbital fat pads

- •

Posterior lamella: Lid retractors, suspensory system, tarsus, conjunctiva

ANTERIOR LAMELLA

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses