Armamentarium

|

History of the Procedure

Throughout history, repair of the bilateral cleft lip deformity has been met with much controversy. The evolution of this technique has been slow, and many of the original techniques were based on the repair of a unilateral cleft lip deformity. The fate of the prolabium has always been a concern. During the late 1600s, there was much debate as to whether the prolabium should be used in the final repair at all. An Englishman by the name of James Cooke was one of the first to advocate saving the prolabium. Even as late as the 1970s, there was still speculation over whether the prolabium could survive the surgical insult from the closure of both cleft sides during the same operation. At that time in the United States, cleft surgeons were divided, with 60% preferring to repair both sides at the same time and 40% advocating a staged technique repairing the more severe side first. Even surgeons who preferred simultaneous closure based their designs on the idea that the prolabium had limited growth potential. With this in mind, the original techniques mainly relied on triangular flaps, rectangular flaps, or straight-line closure variants. Many of these techniques led to large philtral columns, abnormally long lips, or irregular scars, and none of these early repairs addressed the orbicularis oris muscle. During the latter part of the twentieth century, reports began to emerge of the reconstruction of this muscle, and the technique was termed functional cleft lip repair .

History of the Procedure

Throughout history, repair of the bilateral cleft lip deformity has been met with much controversy. The evolution of this technique has been slow, and many of the original techniques were based on the repair of a unilateral cleft lip deformity. The fate of the prolabium has always been a concern. During the late 1600s, there was much debate as to whether the prolabium should be used in the final repair at all. An Englishman by the name of James Cooke was one of the first to advocate saving the prolabium. Even as late as the 1970s, there was still speculation over whether the prolabium could survive the surgical insult from the closure of both cleft sides during the same operation. At that time in the United States, cleft surgeons were divided, with 60% preferring to repair both sides at the same time and 40% advocating a staged technique repairing the more severe side first. Even surgeons who preferred simultaneous closure based their designs on the idea that the prolabium had limited growth potential. With this in mind, the original techniques mainly relied on triangular flaps, rectangular flaps, or straight-line closure variants. Many of these techniques led to large philtral columns, abnormally long lips, or irregular scars, and none of these early repairs addressed the orbicularis oris muscle. During the latter part of the twentieth century, reports began to emerge of the reconstruction of this muscle, and the technique was termed functional cleft lip repair .

Indications for the Use of the Procedure

Prior to surgical repair of the bilateral cleft lip deformity, significant attention should be given to counseling of the family on how to care for a child with this condition, resolution of feeding issues, adequate weight gain, and the overall health of the newborn. Timing of the bilateral cleft lip repair has historically followed the “rule of 10’s,” requiring that the child be at least 10 weeks old, weigh at least 10 pounds, and have a minimum hemoglobin level of 10 mg/dL. With the advancements in pediatric anesthesia and intraoperative monitoring, general anesthesia can be safely administered very early in life. Regardless of this ability, there has been no benefit to repairing the cleft lip deformity prior to 3 months of age. Advantages to waiting until at least 10 weeks of age include improved ease of repair with slightly larger anatomic landmarks and adequate time for the primary care provider to evaluate the patient for other congenital abnormalities.

Technique: Modified Millard for Bilateral Cleft Lip Repair

Step 1:

Intubation and Setup

The patient is placed in a supine position on the operating table with a small shoulder roll for support. A broad-spectrum antibiotic, typically a cephalosporin, is given before surgery as prophylaxis. Before the procedure, to reduce the postoperative inflammatory phase, a combination of short- and long-acting steroids is administered unless contraindicated. After induction, an oral endotracheal tube is secured to the patient’s chin in the midline. After surgical preparation, the anatomic structures are palpated and marked with a sterile surgical pen.

Step 2:

Markings and Local Anesthetic

Anterior Lip

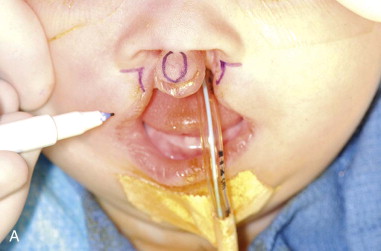

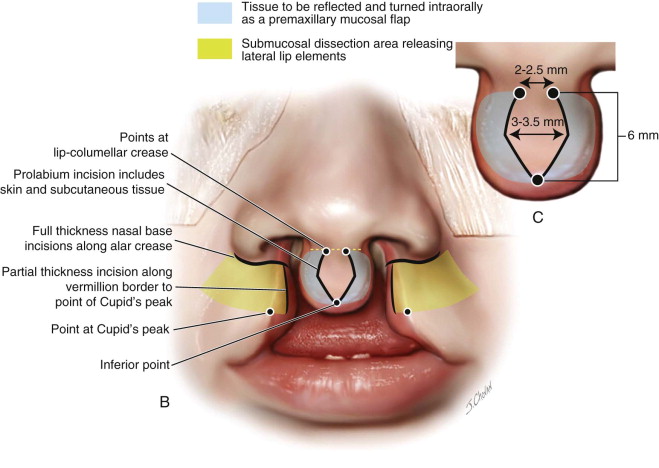

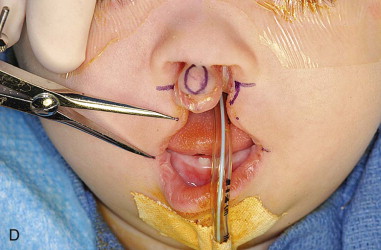

The design of the planned surgical incisions is marked, starting with the prolabium. At the level of the lip-columellar crease in the midline, two points are placed approximately 2 to 2.5 mm apart. The length of the philtral column is then established by marking a point 6 mm inferior to the lip-columellar crease. The widest point on the philtral column, established 1.5 mm superior to the inferior point, is 3 to 3.5 mm in width and forms the peaks of Cupid’s bow. These points are connected to produce the final design of the philtral column. The width of Cupid’s bow and the length of the philtral column are directly related to the age of the patient. Repairs in older patients have less of a tendency to widen over time. The measurements used to design the philtral column should be slightly enlarged in older patients to compensate for this decreased amount of growth potential ( Figure 51-1, A-C ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses