The popularity of cosmetic procedures continues to increase alongside increased media exposure and reality television programming. In 2005 it was estimated that the U.S. population spent $12.4 billion on surgical and nonsurgical cosmetic procedures. Approximately 11.5 million procedures were performed in 2005, and of these 19% were surgical. The number of procedures has increased by 444% since 1997. In 2005 rhinoplasty was the fourth most common procedure overall and the second most common surgery performed in men. Rhinoplasty was also the third most common procedure in teenagers, following hair removal and microdermabrasion or skin treatment.

Cosmetic surgery of the nose is often considered one of the most difficult esthetic operations. This is partly because the nose holds a prominent position on the face and irregularities or asymmetries cannot be easily camouflaged. Also, subtle postsurgical changes will occur over the course of a year or more. If a surgeon does not perform long-term follow-up of patients, he or she will not gain an appreciation for how well his or her surgical techniques withstand the test of time. For many years, cartilage grafting and destructive techniques to the alar cartilages were performed. In the short term, many of these noses would look good. However, with time, some of these techniques have demonstrated unpredictable long-term results. A return to more conservative and nondestructive tip techniques has come back into favor with the hope that long-term favorable esthetic results can be achieved without compromising the nasal airway.

As in any surgery, a solid understanding of the anatomy and physiology is essential. Taking time to listen to the patient’s concerns and desires is critical to help formulate the surgical goals and determine if the patient is suitable for surgery and has realistic expectations. Once the patient decides to proceed with surgery, the surgeon must perform a comprehensive examination, taking into consideration the dynamic influence of the skin type, bone and cartilage structure, and anatomic limitations. Creating a detailed three-dimensional plan with a structured sequence will help the surgeon achieve more predictable results.

Mastering the complexity of rhinoplasty is something that cannot be captured in a single chapter. It takes years of training, experience, and continuing medical education to become comfortable with the many techniques that must be tailored to each patient. This chapter will hopefully provide a foundation to build on.

NASAL ANATOMY

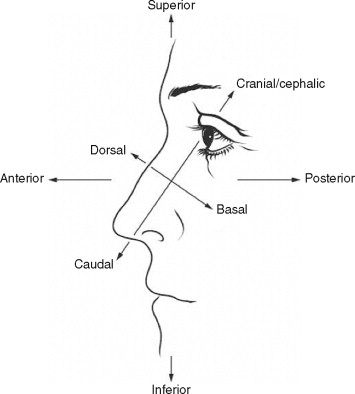

The descriptors used to describe relative spatial relationships include the standard anatomic terms: anterior, posterior, superior, and inferior, as well as dorsal, basal, caudal, and cephalic (or cranial) ( Figure 24-1 ). The terms used to describe the surface anatomy assist the surgeon in defining problem areas of the nose and facilitate treatment planning ( Box 24-1 ).

-

Radix: The deepest depression of the nasal dorsum, located at the junction between the frontal bone and the nasal bones.

-

Glabella: The most forward projecting portion of the forehead, located at the midline between the supraorbital ridges.

-

Rhinion: The osteocartilaginous junction formed by the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages.

-

Dorsum: The anterior surface of the nose formed by the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages.

-

Supratip break: The slight depression seen in profile at the point where the nasal dorsum joins the lobule of the nasal tip.

-

Infratip lobule: The portion of the tip lobule located between the columella and the most projected portion of the nasal tip.

-

Tip defining points: For proper nasal tip definition four points should be visualized. These four points are composed of the supratip break, the infratip lobule, and the most projected portion or domes of the lower lateral cartilages.

-

Alar sidewall: The rounded eminence forming the lateral nostril wall.

-

Alar-facial junction: The depressed groove formed at the junction where the ala joins the face.

-

Columella: The skin that separates the nostrils at the base of the nose.

-

Nasofrontal angle: The angle formed between the forehead and nasal dorsum as seen in profile view.

-

Nasolabial angle: The angle formed by the columella and the upper lip as seen in profile view.

-

Pronasale: The most projected portion of the nasal tip.

The thickness of the skin varies along the dorsum of the nose. In the region of nasion, the skin is fairly thick and mobile. It quickly thins over the nasal dorsum and is generally thinnest and most mobile in the middorsal region (rhinion). In the nasal tip the skin becomes thicker and more adherent and has an increased sebaceous content.

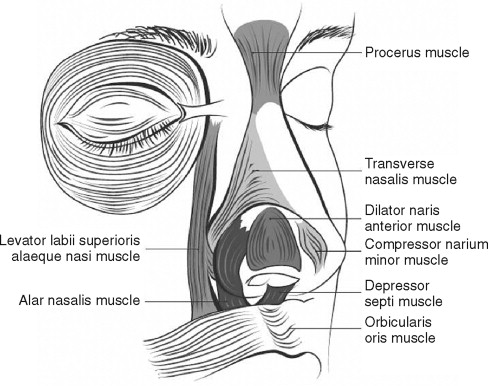

The muscles of the nose are encased in the nasal superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). This is a fibromuscular layer that separates the skin and subcutaneous tissue from the nasal cartilage and bone. The SMAS of the nose is continuous with the SMAS of the face. Violating the SMAS can result in increased bleeding, scarring, and postoperative edema; therefore the dissection should be between the cartilage and bone and the SMAS ( Figure 24-2 ).

The muscles of the nose can be divided into four categories: the elevators, the depressors, the compressors, and the dilators. The paired depressor septi nasi muscles can cause inferior displacement of the nasal tip during smiling. This smiling deformity should be recognized preoperatively and addressed by resection of these muscles in order to achieve a cosmetic result.

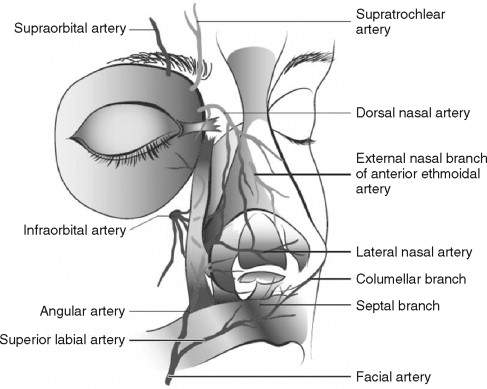

There is a rich blood supply to the subdermal vascular plexus of the external nose, which arises from branches of both the internal and external carotid arteries. The internal carotid artery supplies the external nose via the dorsal nasal artery (a branch of the ophthalmic artery) and the external nasal artery (a branch of the anterior ethmoid artery).

The external carotid artery provides blood supply via the facial artery branches (angular artery, lateral nasal artery, alar artery, septal artery, and superior labial artery) ( Figure 24-3 ).

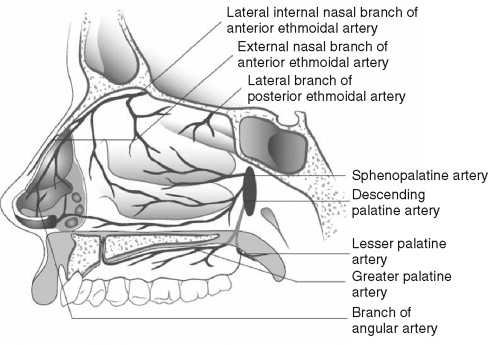

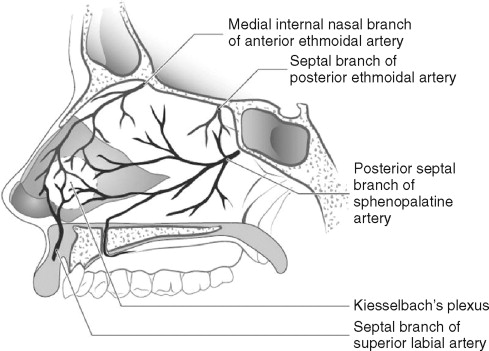

The internal nose is supplied by the internal and external carotid branches ( Figure 24-4 ). From the internal carotid, the ophthalmic artery branches into the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries. The anterior ethmoidal artery supplies the anterosuperior part of the septum and the lateral nasal wall. The posterior ethmoid artery supplies the septum, lateral nasal wall, and superior turbinate. From the external carotid, the internal maxillary artery branches that supply the internal nose include the sphenopalatine artery and the greater palatine artery. The sphenopalatine artery supplies most of the posterior part of the nasal septum, lateral wall of the nose, roof, and part of the nasal floor. The greater palatine artery supplies a portion of the anterior and inferior portion of the nasal septum.

A common site of epistaxis is known as Kiesselbach’s plexus (also termed Little’s area) ( Figure 24-5 ). This area is located in the anteroinferior part of the nasal septum and represents the anastomosis of the sphenopalatine, greater palatine, superior labial artery, and anterior ethmoid arteries. The venous drainage of the nose is primarily from the facial and ophthalmic veins.

One concern during nasal surgery is the possibility of compromised blood flow to the nasal tip if the surgeon performs an external rhinoplasty. Cadaver dissection, lymphoscintigraphic studies, and histologic examinations confirm that the primary blood supply to the nasal tip comes from the bilateral lateral nasal arteries, which course in a plane superficial to the alar cartilages in the subdermal plexus approximately 2 to 3 mm above the alar groove. The blood supply allows a columellar incision to be made without fear of vascular compromise. Some surgeons believe external rhinoplasty remains more edematous for longer postoperative periods because of disruption of veins and lymphatics in the columellar region. Anatomic studies show few veins and minimal lymphatics in this region, and the tip edema noted by some is purely subjective.

The paired nasal bones as well as the frontal process of the maxilla provide support to the upper nose. The nasal bone is thickest where it joins with the frontal bone and tapers as it joins with the upper lateral cartilages. The nasal bones have an intimate connection with the upper lateral cartilages and overlap them by 6 to 8 mm. The connection between the nasal bones and upper lateral cartilages should not be violated because this could result in internal nasal valve obstruction and asymmetry.

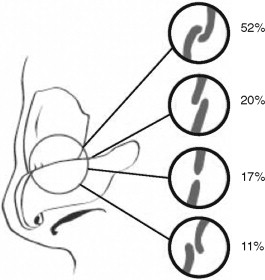

The lower lateral cartilages form the nasal tip and connect with the upper lateral cartilages in a union described as the scroll ( Figure 24-6 ). There are various configurations of the scroll. The scroll is described as interlocked (52%), end-to-end (17%), overlapping (20%), or opposed (11%). The scroll provides significant support to the nasal tip. Removing cephalic strips of cartilage from the lower lateral cartilages or performing an endonasal rhinoplasty violates this junction. The lower lateral cartilage is divided into medial and lateral crura. The medial crura are in intimate contact with the nasal septum and provide tip support. The lateral crura extend superiorly and form dense fibroareolar tissue attachments with the pyriform aperture. The intermediate crus is defined as the area where the medial crura diverge before turning to become the lateral crura proper. The highest point of the intermediate crus is an important surgical landmark known as the tip defining point.

The nasal septum is formed by both bone and cartilage. The ethmoid and vomer provide bony support posteriorly. The quadrangular cartilage provides support anteriorly.

Support for the nasal tip is classified into major and minor divisions. The major tip support comes from the size, shape, and strength of the lower lateral cartilages, the attachment of the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilage to the caudal septum, and the fibrous attachment of the lower lateral cartilage to the upper lateral cartilage. The minor tip support comes from the nasal spine, the membranous septum, the cartilaginous dorsum, the sesamoid complexes, the interdomal ligaments, and the alar attachments to the skin.

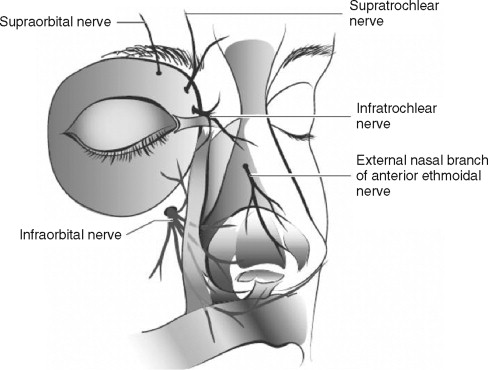

The sensory nerve supply to the skin of the external nose is supplied by the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the trigeminal nerve ( Figure 24-7 ). Branches of the supratrochlear and infratrochlear nerves supply the skin in the region of the radix and rhinion. The lower half of the nose is supplied by the infraorbital nerve and the external nasal branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve (a branch of the nasociliary nerve that arises from the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve).

The main sensory nerve supply to the nasal septum comes from the internal nasal nerve (a branch of the anterior ethmoidal nerve) and the nasopalatine nerve. The lateral nasal wall sensation is supplied by the anterior ethmoidal nerve, branches of the pterygopalatine ganglion, branches of the greater palatine nerve, the infraorbital nerve, and the anterior superior alveolar nerve.

THE CONSULTATION

In cosmetic surgery the initial consultation is probably the most important appointment. During this visit the patient will decide if he or she trusts you and your staff enough to proceed with surgery. From the surgeon’s perspective, it is important to determine if the patient is a suitable candidate for cosmetic surgery and that he or she has realistic expectations.

First, determine the area of the nose that bothers the patient the most. It is sometimes helpful to have the patient point the areas out with a cotton tip applicator in the mirror. Next, pertinent history should be obtained. Has the patient had previous cosmetic surgery? If so, what were his or her experience and satisfaction with the procedures? Be wary of patients who seek a different doctor for each procedure and denigrate the previous surgeon. Also, be concerned if the patient offers excessive praise about you or your reputation and states that he or she knows you will be able to correct the previous surgical errors made by the last doctor. Other important history should include previous trauma, nasal and septal surgeries, difficulties with nasal breathing, allergies, cocaine use, and the use of intranasal medications. If the patient has had previous septal surgeries, prepare the patient for the possible need for auricular cartilage harvesting in the event that you need cartilage at the time of surgery.

Reviewing photographs will also help you make better judgment of the patient’s expectations. Patients who are overly critical may not be good candidates for surgery. Imaging is not entirely accurate and is best used to show something simple, such as what the reduction of a dorsal hump would do for the profile or the benefits of chin augmentation.

It is essential to determine those patients who are unsuitable from a psychiatric standpoint to undergo the operation. It is estimated that 5-7% of all cosmetic surgery patients have a diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder. In rhinoplasty surgery the incidence may be as high as 20.7%. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), the following criteria must be met for a patient to be diagnosed: the patient is preoccupied with an imagined defect of appearance or is excessively concerned about a slight physical anomaly; this preoccupation causes clinically important distress or impairs work, social, or personal functioning; and another mental disorder (such as anorexia nervosa) does not better explain the preoccupation. Those patients with body dysmorphic disorder seeking rhinoplasty tend to be younger, more depressed, more anxious, and preoccupied with the nose, as demonstrated by frequent touching and looking in the mirror. Cosmetic surgeons should be aware of this disease because the suicide rate has been found to be 45 times higher than in the general population.

It is also wise to avoid operating on someone whom you just do not like. If your personalities clash, it is best to avoid doing the surgery. You need to ask yourself if you could manage such a patient if a complication were to arise.

Patients are typically seen again the week before surgery for their preoperative appointment, at which time photographs are taken. An additional set of photographs is taken the morning of surgery. It is important when taking photographs of the nose to obtain six main views, including full-face frontal, full-face right and left oblique, full-face right and left lateral, and basilar views. Standardization of photographic technique is essential for proper operative planning and for obtaining high-quality before and after photographs to be used in future consultations.

THE CONSULTATION

In cosmetic surgery the initial consultation is probably the most important appointment. During this visit the patient will decide if he or she trusts you and your staff enough to proceed with surgery. From the surgeon’s perspective, it is important to determine if the patient is a suitable candidate for cosmetic surgery and that he or she has realistic expectations.

First, determine the area of the nose that bothers the patient the most. It is sometimes helpful to have the patient point the areas out with a cotton tip applicator in the mirror. Next, pertinent history should be obtained. Has the patient had previous cosmetic surgery? If so, what were his or her experience and satisfaction with the procedures? Be wary of patients who seek a different doctor for each procedure and denigrate the previous surgeon. Also, be concerned if the patient offers excessive praise about you or your reputation and states that he or she knows you will be able to correct the previous surgical errors made by the last doctor. Other important history should include previous trauma, nasal and septal surgeries, difficulties with nasal breathing, allergies, cocaine use, and the use of intranasal medications. If the patient has had previous septal surgeries, prepare the patient for the possible need for auricular cartilage harvesting in the event that you need cartilage at the time of surgery.

Reviewing photographs will also help you make better judgment of the patient’s expectations. Patients who are overly critical may not be good candidates for surgery. Imaging is not entirely accurate and is best used to show something simple, such as what the reduction of a dorsal hump would do for the profile or the benefits of chin augmentation.

It is essential to determine those patients who are unsuitable from a psychiatric standpoint to undergo the operation. It is estimated that 5-7% of all cosmetic surgery patients have a diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder. In rhinoplasty surgery the incidence may be as high as 20.7%. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition (DSM-IV), the following criteria must be met for a patient to be diagnosed: the patient is preoccupied with an imagined defect of appearance or is excessively concerned about a slight physical anomaly; this preoccupation causes clinically important distress or impairs work, social, or personal functioning; and another mental disorder (such as anorexia nervosa) does not better explain the preoccupation. Those patients with body dysmorphic disorder seeking rhinoplasty tend to be younger, more depressed, more anxious, and preoccupied with the nose, as demonstrated by frequent touching and looking in the mirror. Cosmetic surgeons should be aware of this disease because the suicide rate has been found to be 45 times higher than in the general population.

It is also wise to avoid operating on someone whom you just do not like. If your personalities clash, it is best to avoid doing the surgery. You need to ask yourself if you could manage such a patient if a complication were to arise.

Patients are typically seen again the week before surgery for their preoperative appointment, at which time photographs are taken. An additional set of photographs is taken the morning of surgery. It is important when taking photographs of the nose to obtain six main views, including full-face frontal, full-face right and left oblique, full-face right and left lateral, and basilar views. Standardization of photographic technique is essential for proper operative planning and for obtaining high-quality before and after photographs to be used in future consultations.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

When performing an examination of the nose, both the esthetics and function must be assessed. The examination should be done in a thoughtful and systematic way to ensure that nothing is overlooked. I typically begin with the external nasal examination and finish with the intranasal speculum examination.

UPPER NOSE AND DORSUM

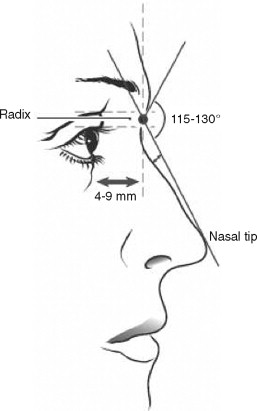

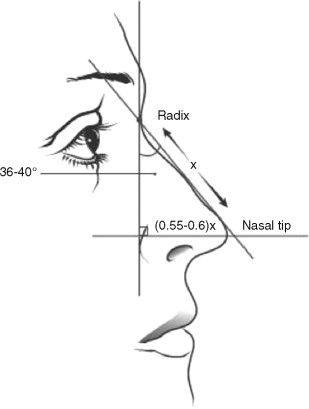

The upper nose and dorsum are assessed first. From the frontal view, note any gross asymmetries, lateral bony irregularities, or deviation of the dorsum. Next, determine if the width of the upper nose is adequate or excessive. The upper nasal width should be approximately 80% of the alar width, assuming that the alar width is not excessive. Normal alar width should approximate the patient’s intercanthal distance. In a profile view, evaluate the position of the radix (the greatest depth of the nasofrontal depression). The radix should be located vertically between the superior palpebral margin and the upper eyelid margin. The nasal length (distance from radix to nasal tip) is also affected by the position of radix. If the radix is low, the patient will have the appearance of a short nose, and if it is high, the patient will have the appearance of a long nose.

In the profile view the depth of the nasofrontal depression should be approximately 4 to 9 mm anterior to the corneal plane ( Figure 24-8 ). The depth of the radix can greatly affect the nasofrontal angle. The ideal nasofrontal angle is between 115 and 130 degrees. The nasofrontal angle tends to be more acute in men and more obtuse in women. A deep radix creates a more acute nasofrontal angle and a shallow radix creates a more obtuse angle. When examining the nose in profile, also note any dorsal hump deformities.

NASAL TIP

Control of the nasal tip is critical in rhinoplasty surgery. Proper assessment of the problems with the nasal tip is important in planning the surgical technique. The shape of the nasal tip itself should be evaluated first. Is the tip bulbous, boxy, pinched, twisted, or asymmetric? Next, look at the tip definition. There should be four tip defining points including the supratip, the infratip, and the most prominent portion of the intermediate crus (the junction between the medial crura and lateral crura of the lower lateral cartilage). From the profile view, identify the supratip break and the infratip break (also known as the columellar-lobule angle ). The distance from the supratip break to the infratip break should be divided equally by a line drawn parallel to the floor through the pronasale (the most forward point of the tip of the nose).

The tip projection and support should be assessed next. The nose should not be easily compressible when pushing on the nasal tip with an index finder. If the cartilages are weak and the nose is easily compressed, consideration should be given to crural strut grafts to increase support. There are several ways to evaluate the tip projection. No one method is superior, and each method has its limitations. The most commonly quoted method is Goode’s method. This definition states that the ideal tip projection is 0.55 to 0.6 RT, where RT is the distance between radix and pronasale ( Figure 24-9 ). Tip projection is usually measured as the distance from the alar groove to the most projected portion of the nasal tip (pronasale). Simon’s method states that the length of the upper lip from subnasale to labrale superioris should be equal to the tip projection measured from subnasale to pronasale. Another method is to draw a tangent through the most projected portion of the upper lip. This line should bisect the nose such that 50% is tip and 50% is nasal base. If more than 60% is nasal tip, the nose is considered overly projected.

The relationship of the dorsum to the nasal tip should also be evaluated. The dorsum should be approximately 2 mm below a line drawn from radix to pronasale in women and just below or even with the line in men.

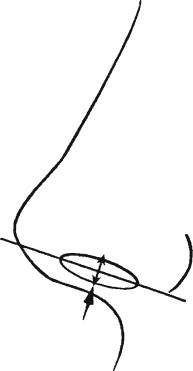

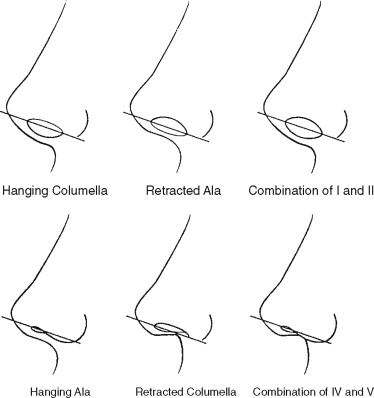

The columella is then assessed. First, look at the columellar-lobular angle. This is defined as the angle created where the tangents of the columella and infratip lobule intersect. A normal columella-lobular angle is 36 to 40 degrees. Next, the relationship of the ala and columella is assessed. From the profile view, imagine a line drawn from the base of the nostril to the tip of the nostril that bisects the ala and the columella ( Figure 24-10 ). In a properly proportioned nose, the columella and alar rim should be equidistant from the line, and approximately 2 to 4 mm of columella should show. When there is a large amount of columella showing, the problem may be due to a hanging columella, alar retraction, or a combination of both ( Figure 24-11 ). Conversely, if there is little columella showing in the profile view, the problem could be with a retracted columella, a hanging ala, or a combination of both. Determining the problem is essential because the management of each of these problems is different.

The nasal tip rotation is then evaluated. This is often measured by using the nasolabial angle. This angle is formed by the intersection of the tangents of the columella and the upper lip. A normal nasolabial angle is 95 to 110 degrees in women and 90 to 95 degrees in men. This angle can be affected by the inclination of the upper incisor teeth.

While the patient is evaluated in profile, the chin projection relative the nose should not be overlooked. Often a nose looks much larger when the patient has a weak chin. A simple method to evaluate chin position is to look at the relative position of the chin to the subnasale perpendicular. In a profile view a woman’s chin should be on or slightly behind an imaginary vertical line from the subnasale perpendicular, and in men it should be on or slightly in front of this line. Consideration for a chin implant or genioplasty should be done in cases of microgenia to keep the nose and chin in better balance.

SKIN THICKNESS

The nose should be palpated to assess the skin thickness. A patient with thin nasal skin will show dramatic changes with alteration of the underlying bone and cartilage, and this limits room for error because little is camouflaged by the thickness of the skin. On the other hand, thick-skinned individuals require more aggressive sculpting of the nasal skeleton in order to see significant change. Although thick skin may mask imperfections, it does not re-drape as well and can result in underlying fibrosis and formation of a polybeak deformity (supratip scarring). Better results are possible with average to thin-skinned patients; however, the margin for error is smaller.

NASAL FUNCTION

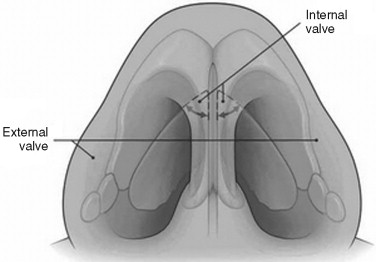

Lastly the functional aspects of the nose must be evaluated. Have the patient breath normally through the nose, then have him or her take a deep breath through the nostrils. Observe for collapse of the ala and occlusion of nasal breathing. The airflow through the nose is regulated by the internal and external nasal valves. The external nasal valve is formed by the lower lateral cartilage ( Figure 24-12 ). In severe cases, collapse of the external nasal valve can be seen when the nares become occluded on even gentle inspiration. This problem is more common in patients with narrow nostrils, overly projected nasal tip, and thin alar sidewalls. External nasal valve collapse is also commonly seen in patients having previous rhinoplasty surgery with excessive trimming of the cephalic portion of the lower lateral cartilages. It may also be seen with increased age and in facial nerve paralysis. The external nasal valve collapse can be corrected by deprojecting an overprojected nose, realigning the lateral crura into a more caudal orientation, and placing alar batten grafts to provide structural support and prevent collapse.

The internal nasal valve is formed by the junction of the septum and the upper lateral cartilages (see Figure 24-12 ). The angle formed should be a minimum of 10 to 15 degrees to maintain patency. Deviation of the nasal septum or separation of the upper lateral cartilages from the nasal bones can lead to obstruction. This problem is also seen after rhinoplasty if the patient has had weakening of the upper and lower lateral cartilages. These patients often have a pinched appearance in the supraalar region. The Cottle test is used to evaluate obstruction at the internal valve by using a finger to laterally pull the cheek and lateral wall of the nose, thereby opening the nasal valve. Nasal airflow that is dramatically improved by the Cottle test indicates that the internal nasal valve requires correction. These patients often achieve symptomatic relief by the use of external taping devices. Surgical correction involves the placement of spreader grafts between the septum and upper lateral cartilages and/or cartilage flaring sutures to increase the angle of the lower lateral cartilages with the nasal septum 22, ( Figure 24-13 ).

The nose is inspected last with a nasal speculum. Observe for any deflections or perforations of the nasal septum, bone spurs, enlargement of turbinates, or any nasal pathology.

PLANNING

In preparation for surgery, it is helpful to review the presurgical photographs and compile a problem list. The surgeon should have a clear plan as to what techniques will be employed to address the various problems and the sequence in which these problems will be corrected.

INCISIONS FOR RHINOPLASTY

There are a number of incisions commonly used in rhinoplasty. The choice of incision is determined by whether an open or closed rhinoplasty is performed.

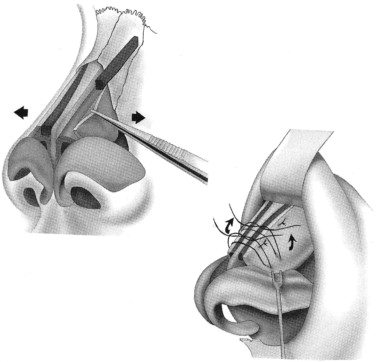

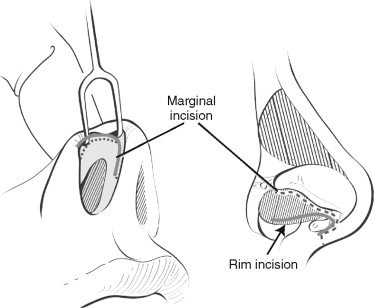

Marginal incisions connected by a transcolumellar incision are commonly used in open rhinoplasty ( Figure 24-14 ). The marginal incision parallels the caudal edge of the lower lateral cartilages. The incision begins just caudal to the lateral crus and parallels the caudal edge of the lower lateral cartilage until the medial crura begin to flare. It differs from a rim incision in that the rim incision parallels the alar rim. The problem with a rim incision is that the soft tissue caudal to the lateral crus is disrupted, which can result in scarring and alar retraction.

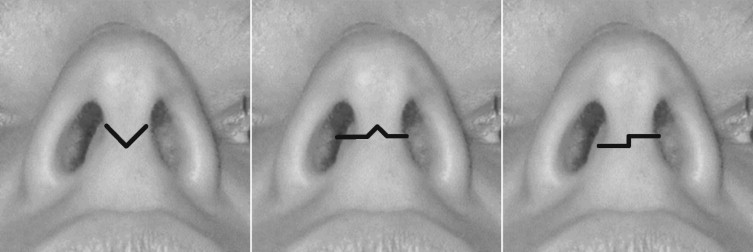

The transcolumellar incision is used to connect the bilateral marginal incisions and allows the soft tissues overlying the nasal tip to be elevated in open rhinoplasty. The incision is made just superior to the flare of the medial crura. To prevent linear scar contraction and to facilitate closure, the incision is broken up by using a V, inverted V, or stairstep configuration ( Figure 24-15 ).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses