HISTORY

Tagaki performed the first arthroscopic examination in 1918. He used a cystoscope to look at a cadaver knee. Several further attempts to look into the knee joint were made, but the equipment was problematic. Watanabe then developed several working arthroscopes and described their use in various joints in 1957. Fiberoptic lighting was incorporated in the 1970s, which allowed for reproducible examination. In 1975, Ohnishi used a Watanabe small-joint arthroscope to enter the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Sanders brought the Japanese techniques to the United States, and others, like Holmlund in Sweden, developed diagnostic uses for the arthroscope. Murakami published descriptions of the arthroscopic anatomy and pathology in 1982. The main operative usage of arthroscopy in the United States became the lysis and lavage procedure popularized by Sanders and others. Operative arthroscopy in the TMJ was first limited by the size of the joint and the lack of miniaturization of instruments that had been developed for the knee. The use of fiberoptic laser delivery in the 1980s by Indresano and Braderick and by Koslin advanced operative capabilities. McCain developed suturing techniques that allowed operative arthroscopy to rival open arthroplasty for disk stabilization. Later Dolwick and Nitzan showed that a simple procedure known as arthrocentesis, and performing a lysis and lavage without putting the arthroscope into the joint, gave similar results. Today, therefore, arthroscopic lysis and lavage has been all but replaced by arthrocentesis. Operative arthroscopic arthroplasty is used for more advanced maneuvers by those able to perform them. A modern surgical algorithm for internal derangement will generally include arthrocentesis and may use operative arthroscopic surgery or open surgery as the next step. This has decreased the volume of arthroscopic procedures that were performed in the 1980s and early 1990s.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The general anatomy of the TMJ is described in Chapter 48 . There are several special anatomic concerns that must be mentioned pertaining specifically to arthroscopy. Anatomic landmarks, first enumerated by Murakami, added new terms to those anatomic structures established from dissection.

The volume of fluid in the upper and lower compartments is important to understand. The volume of the normal upper joint space is about 2 mL, but it can increase to as much as 6 mL with pathology. The lower space volume is about 1 mL and can increase to 2 mL. Knowing this is essential when the initial joint puncture and joint insufflation is attempted to prevent a capsular tear.

The joint functions with a complex rotation and sliding motion. The upper compartment is involved in the sliding motion, and most mechanical hindrances and pathologic entities occur here. This is the reason that most arthroscopic surgery is performed in the superior joint space. Since inferior joint space arthroscopy is much more technically difficult to perform, it is quite fortunate that the upper space is where arthroscopy can achieve desired results.

In either the upper or the lower compartment, one must verify that sufficient joint space exists to establish and maintain fluid flow and to accept arthroscopic portals. The ligamentous and capsular structures are thin in the normal joints and can easily be violated by too many puncture attempts, or from too much fluid distention. Attempts to pass an arthroscope in severely fibrosed or bony ankylosed joints are subject to major complications. With pathologic changes, these structures are much more substantial and can be difficult to traverse.

It is imperative that the anatomy of the region specific to arthroplasty be understood before attempting arthroscopic surgery. The bony roof can be interrupted by a sharp trocar in the deep superior portion of a thin mandibular fossa. The proximity of the external auditory canal must be considered. In a large patient, the mandibular fossa position may be topographically difficult to differentiate from portions of the external and even the middle ear. The temporal vessels and the facial nerve are also of great concern during the puncture maneuver. Injuries to these structures will be described under Complications.

Finally, arthroscopy should not be attempted by anyone not capable of performing open joint surgery. If bleeding occurs or instruments break, it may be necessary to surgically explore the joint. One should always be prepared and have informed consent for that eventuality.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

The general anatomy of the TMJ is described in Chapter 48 . There are several special anatomic concerns that must be mentioned pertaining specifically to arthroscopy. Anatomic landmarks, first enumerated by Murakami, added new terms to those anatomic structures established from dissection.

The volume of fluid in the upper and lower compartments is important to understand. The volume of the normal upper joint space is about 2 mL, but it can increase to as much as 6 mL with pathology. The lower space volume is about 1 mL and can increase to 2 mL. Knowing this is essential when the initial joint puncture and joint insufflation is attempted to prevent a capsular tear.

The joint functions with a complex rotation and sliding motion. The upper compartment is involved in the sliding motion, and most mechanical hindrances and pathologic entities occur here. This is the reason that most arthroscopic surgery is performed in the superior joint space. Since inferior joint space arthroscopy is much more technically difficult to perform, it is quite fortunate that the upper space is where arthroscopy can achieve desired results.

In either the upper or the lower compartment, one must verify that sufficient joint space exists to establish and maintain fluid flow and to accept arthroscopic portals. The ligamentous and capsular structures are thin in the normal joints and can easily be violated by too many puncture attempts, or from too much fluid distention. Attempts to pass an arthroscope in severely fibrosed or bony ankylosed joints are subject to major complications. With pathologic changes, these structures are much more substantial and can be difficult to traverse.

It is imperative that the anatomy of the region specific to arthroplasty be understood before attempting arthroscopic surgery. The bony roof can be interrupted by a sharp trocar in the deep superior portion of a thin mandibular fossa. The proximity of the external auditory canal must be considered. In a large patient, the mandibular fossa position may be topographically difficult to differentiate from portions of the external and even the middle ear. The temporal vessels and the facial nerve are also of great concern during the puncture maneuver. Injuries to these structures will be described under Complications.

Finally, arthroscopy should not be attempted by anyone not capable of performing open joint surgery. If bleeding occurs or instruments break, it may be necessary to surgically explore the joint. One should always be prepared and have informed consent for that eventuality.

NORMAL ARTHROSCOPIC ANATOMY

SUPERIOR (UPPER) COMPARTMENT

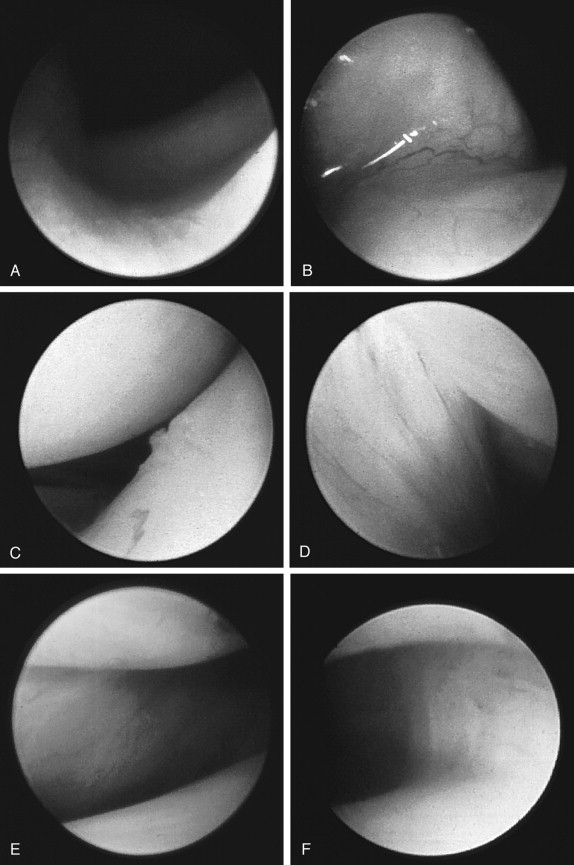

Puncture places the arthroscope in the superior space, showing the medial capsule. The synovium is glistening white with a shiny consistency ( Figure 49-1, A ). Posteriorly the synovium folds over the posterior attachment, which is richly vascular, but the vessels are crisp and discrete. When inflammation is present, however, the vascular region is diffuse and blurred. In the normal joint, the posterior band of the disk is raised and glistening but not vascular ( Figure 49-1, B ). The normal disk is white and smooth with no visible vascularity ( Figure 49-1, C ). A folded posterior attachment has been labeled the oblique protuberance and signifies a ligamentous band ( Figure 49-1, D ). The anterior wall is reflected over the pterygoid muscle and is very thin and translucent ( Figure 49-1, E ). Posteriorly and medially the medial capsule is seen ( Figure 49-1, F ). The consistency changes from thin to thick as one moves more posteriorly. The lateral capsule is not easily seen from the inferolateral approach.

INFERIOR (LOWER) COMPARTMENT

Generally, vascularity is not seen in the lower compartment. The surfaces are glistening and smooth, as is the condylar cartilage cap. Views of the lower compartment can be seen in Figure 49-1, G-I . Because of the small volume and narrow recesses, generally not much is seen and one must be suspect that the scope itself may cause seemingly pathologic changes.

DIAGNOSTIC USES

When temporomandibular joint arthroscopic examination was first performed, its diagnostic usefulness was felt to be the primary benefit. After more than 20 years used as a common tool, direct visualization of the joint is not routinely needed for diagnosis. Although many forms of joint pathology can occur in the TMJ, there may be no correlation with changes in the synovial or cartilage surfaces. Therefore diagnostic arthroscopy must be used in conjunction with history, clinical signs, and imaging to formulate a diagnosis in the TMJ patient.

The main abnormality seen in the temporomandibular joint is the internal derangement/osteoarthritis continuum categorized by the Wilkes classification. Arthroscopy can be most useful in staging this disease and determining treatment options.

Other arthritides are seen, with rheumatoid arthritis being the most common, but arthroscopy is rarely, if ever, the deciding factor in diagnosis. Diagnosis and treatment of traumatic conditions may be helped by arthroscopic evaluation. Biopsy is essential if dealing with the very rare tumor that may occur.

PATHOLOGY

INTERNAL DERANGEMENT

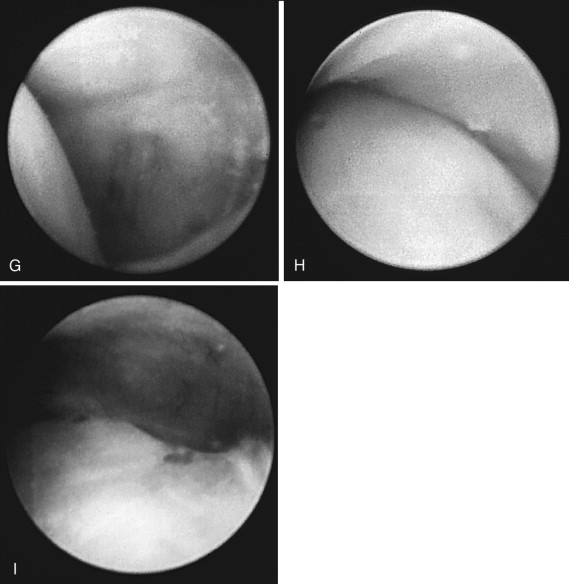

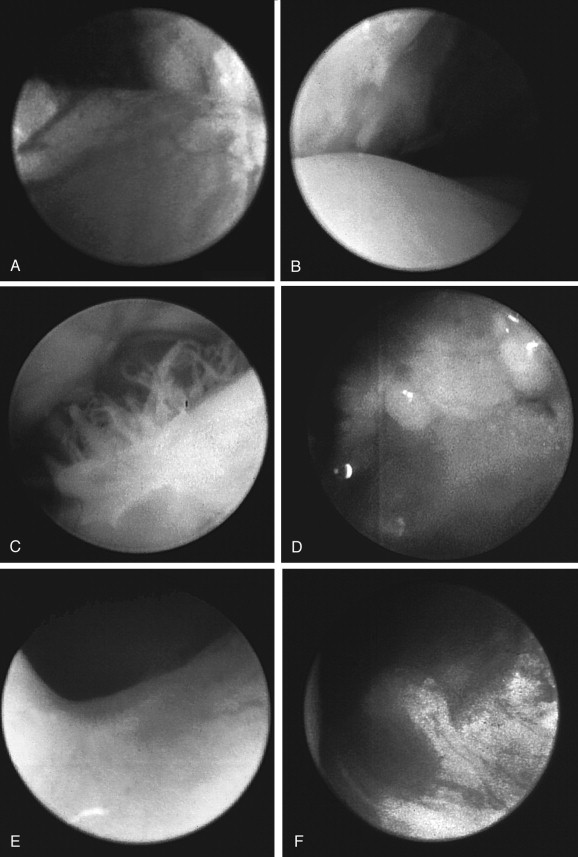

Although the most common condition to be treated with arthroscopy, internal derangement shows various levels of nonspecific changes that are mostly attributed to inflammation. Increased vascularity in the posterior attachment, vessels encroaching onto the avascular disk, and blurring of vascular markings may all be seen. Signs of cartilage degeneration in later stages may also be seen. This information may direct the operative therapy when performing arthroscopic surgery, such as the use of laser, anti-inflammatory medications, or lubrication therapy. It might also indicate the need for an open procedure if an undiagnosed perforation in the disk is seen ( Figure 49-2 ), depicting various pathologic conditions.

FLUID ANALYSIS

Analysis of joint fluid has brought a greater understanding of the degradation process in internal derangement as well as theories for the causation of pain emanating from the joint. Substances such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) have been shown to be markers predicting outcome in lysis and lavage for chronic closed lock. Fluid analysis will be discussed elsewhere.

EQUIPMENT

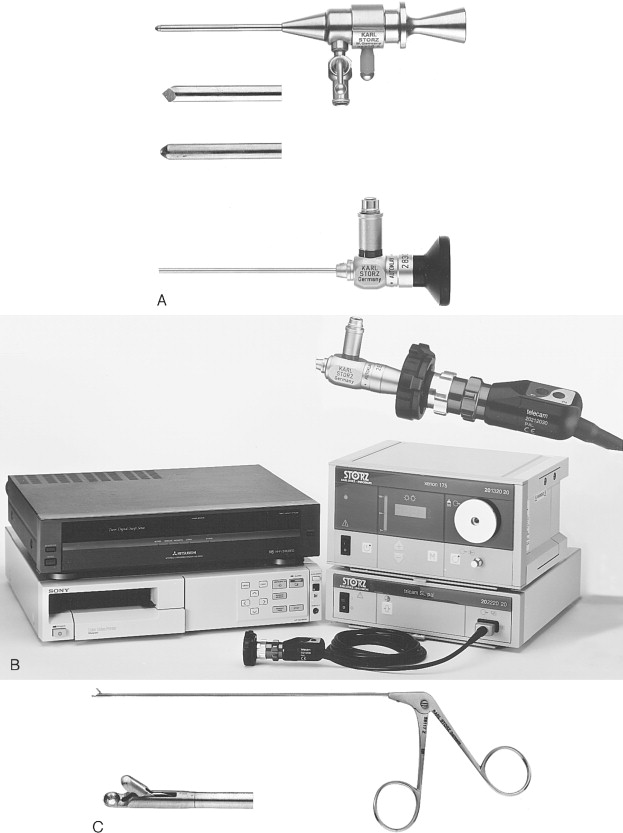

There is much written about arthroscopic equipment, especially at the advent of its use. Figure 49-3 shows a typical equipment set-up. Telescopes run from 0.7 to 2.7 mm in diameter. The angle of view can range from zero to 35 degrees. Generally an angled arthroscope is better for visualization of all areas, and a zero-degree arthroscope is better for operative techniques that include triangulation. Various light and camera systems are available. A complex 3-chip camera will give the best video reproduction. There has not been much research and development in TMJ arthroscopic equipment recently. Manufacturers have concluded that there is not a large market for this equipment in the United States. With most joint lavage now being accomplished through arthrocentesis, only a few changes in arthroscope design have occurred. These have been accomplished in Japan, and much of the newer equipment is not exported to the United States.

ARTHROSCOPIC PUNCTURE—THE INFEROLATERAL TECHNIQUE

Arthroscopy is very technique-sensitive. There is a large learning curve to master before feeling comfortable performing this procedure effortlessly. Partly, this is due to the process of learning to operate while watching a monitor and making very minor hand movements to achieve objectives, and partly from complications that can occur if not performed skillfully.

Arthroscopy can be undertaken with the patient receiving a local anesthetic, but this is usually a single-puncture observation of the joint, possibly with biopsy. Most often it is performed with the patient receiving a general anesthetic in an operating room, especially if multiple punctures are used and operative equipment such as lasers are required.

Peri-operative antibiotics directed to prevent skin contamination and glucocorticoids for edema management are often used. The patient is placed in the supine position on the operating table and receives nasal endotracheal intubation. Preparation of the skin with povidone iodine or comparable antibacterial solution is performed. After the surgical field is isolated, circular holed aperture (eye) drapes are affixed anteriorly over the ear to provide an isolated field in front of the ear. Neurosurgical drapes may be helpful in keeping the copious irrigating fluid off the floor and shoes.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses