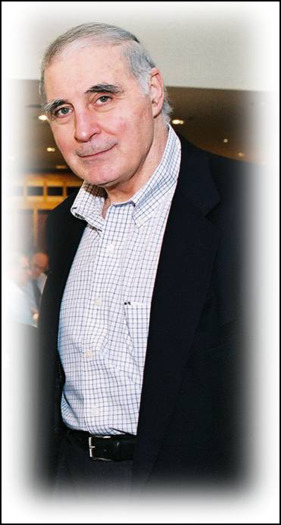

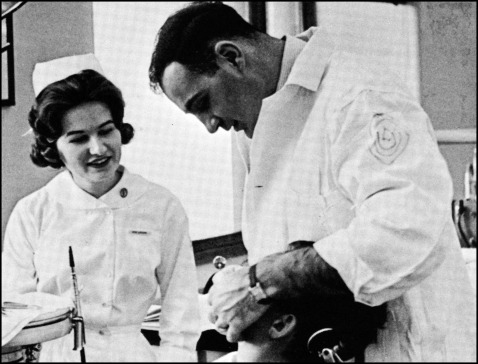

Anthony Gianelly was an iconic figure in the orthodontic specialty ( Fig 1 ). He graduated from Harvard College in 1957, received his DMD degree from the Harvard School of Dental Medicine in 1961, and earned a Certificate in Orthodontics from the Harvard Forsyth Dental Center in 1963 ( Fig 2 ). He then completed a PhD degree in biology and biochemistry at Boston University (BU) in 1967 and, lastly, received an MD degree at the Boston University School of Medicine in 1974. His accolades and awards are too numerous to list, but it might be safe to say that he would be proudest of the Louise Ada Jarabak Memorial International Teachers and Research Award, since it encompassed his love of teaching and his dedication to research. Sadly, he received this award at the national meeting just a few weeks before his untimely death in June 2009.

It would be a grave underestimation to assume that the 3 doctoral degrees and numerous awards summed up Tony’s professional career. During his tenure as chair of the orthodontic department at BU’s Goldman School of Dental Medicine, Tony authored or coauthored 88 journal articles and 3 orthodontic textbooks. He was “evidenced-based” long before the term became popular, and he instilled in his residents the need to critically evaluate the literature and not blindly accept presentations that were unsupported. Tony believed that anecdotal information was useless until it stood up to the critical test of statistics. Always in demand as a speaker or moderator, Tony became the “devil’s advocate” for the orthodontic specialty. Frequently, he challenged presenters at conferences to support their presentations with evidence-based data and reminded the audience that it was their duty to question the presentations and demand statistical evidence. Tony’s command of the orthodontic literature was unmatched to the point where he sometimes recalled for other authors the exact content of their articles. His ability to remember articles led his colleagues in Italy to nickname him the “Walking Library”!

Tony’s gifts as a lecturer, a researcher, and an author were dwarfed by his abilities as a teacher. He had a unique ability to present material to his residents in such a way that by the end of the lecture, everyone clearly understood. With minimal effort, he could discover why a concept was not “clear” to everyone, and then he would present it so that they would grasp every detail. His style of teaching was unique, prompting Jim Ackerman’s complimentary observation characterizing Tony as the “ultimate minimalist.” Tony would quickly absorb a concept or problem and then simplify it and develop a solution unique to the situation. He had an uncanny ability to distill articles and chapters and then summarize them in a few well-chosen sentences.

Upon accepting the position of orthodontic chair at BU, Tony prepared by reading every possible orthodontic article all the way back to the 1940s (notes from his personal files clearly support this). He then put together a reading list of the most pertinent articles, and he revised this list biannually, adding new citations and culling out those that had been superseded, to maintain the relevance for his residents.

Before they entered the BU program, residents would receive several monographs written by Tony, detailing what he considered to be the essential elements necessary to practice clinical orthodontics. They were expected to fully “digest” this information before arriving. Often, he was overheard telling residents who had questions to reread the monographs, or he would take them to the journals and select several pertinent articles for them to read. Then he would invite them to return for an in-depth discussion designed to respond to their questions in a clear evidence-based fashion.

Literature seminar reviews with Tony were always a challenge and simultaneously a delight for the residents. He divided the residents into teams, assigned topics, and suggested the pertinent literature to review. Upon completing the course, each team was responsible for writing up the seminar and summarizing the material that the team members had reviewed. Many residents still cherish their summaries to this day.

Tony had a unique view of how a clinical orthodontic program should begin. First, he assumed that everyone had read the monographs he had prepared and had an initial grasp of the basic concepts. Soon after they arrived, the residents would be in the clinic undertaking basic procedures well before they had any idea of the treatment approach. The sooner one was in the clinic banding or bonding the patient, the greater the opportunity to complete treatment in the confines of the program’s duration. At the same time, the residents received instructions in growth and development and were introduced to a space analysis that made treatment planning quite simple. One could band and bond and plan treatment long before understanding orthodontics. As a clinical instructor, his style was to encourage discussion and never tell a resident what should be the correct or ideal approach. He would ask questions and engage the student in a dialog, the goal of which was to intellectually develop the resident so that he or she could provide potential answers and subsequently a logical treatment approach. No concept was ever disparaged, and no idea was ever considered stupid or unacceptable. Frequently, he would encourage residents to try their treatment plan, realizing that they would learn whether it would work, as long as the plan was safe and reasonable for the patient.

One of Tony’s significant contributions to the field was the “Bidimensional Technique.” In keeping with his minimalist philosophy, he believed that techniques were becoming too complicated and cumbersome, and he wanted to simplify everyday practice. Using his time-honored space analysis and widely accepted concepts of anchorage, he developed a technique that proved to be uncomplicated, easily reproducible, and applicable to all clinical situations.

Educators are well aware that taking on the task of chair and program director demands far more than teaching. Tony never let his rise to chair interfere with his dedication as a teacher and leader. His students were always his number one priority, and there are legendary stories of Tony leaving meetings at BU well before they ended so that he could return to his students. His residents are eternally grateful to him for his unparalleled dedication to them.

As an educator, Tony’s approach was unique, starting with his method of selecting a class and continuing with his ongoing, caring relationship with each student. He eschewed interviews, relying solely on 3 markers: grade point average, national board scores, and class rank. Many residents arrived to the program without meeting Tony and without ever visiting the school. Alumni reviews have always shown that there were few if any regrets. The stories of his dedication to students are legendary. While pursuing his MD degree, he was required to attend hospital rounds, sometimes nightly, and he would always be present in the clinic by 8:00 am the next morning. At times, he would be reading a text on obstetrics while simultaneously answering a resident’s question on growth and development.

All of his achievements, degrees, awards, and academic positions never altered Tony’s personality and his down-to-earth relationship with his students both at BU and in Italy. Residents were proud to attend conferences and declare themselves students of Tony Gianelly. He loved to socialize with his students and took every opportunity to gather them for dinners or school parties where everyone was treated as his equal. He was rarely known as “Dr Gianelly” and preferred to be called simply “Tony.” He was the guy you would have a beer with and discuss the Red Sox, Patriots, or Celtics. His residents were motivated to perform, not by grades or evaluations, but because no one wanted to disappoint him or let him down. He had a “boiling point” when things went awry, but it was well understood that it was momentary; within seconds, all would be forgotten, and the situation would return to the happy BU family we all were so fortunate to experience.

Tony’s prowess went well beyond the borders of orthodontics. In high school, he was big in track and field and even held the national shot put record for a time. As an undergraduate at Harvard, he was an All American fullback on the varsity football team and a star on the track team, excelling at discus and shot put. As chair at BU, he enjoyed playing touch football and baseball with the residents and could hit a ball out of the park and onto the expressway. He was an accomplished pool player as well. He taught himself to play the piano and rarely missed the opportunity to play when one was close. When he went to Italy to teach, he taught himself Italian, and even though, according to the Italians, his grammar was not perfect, we were all impressed! In short, Tony Gianelly was everyman, and we were all convinced that he could do anything his heart desired.

We are grateful for having the opportunity to study with Tony, to experience his friendship, and to spend decades learning and teaching with him. We miss you, Tony, and we’ll never forget you. Think about him the next time you hear Sinatra sing “My Way”!

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses