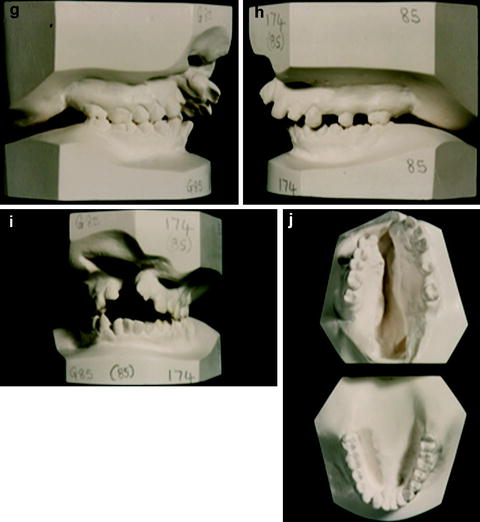

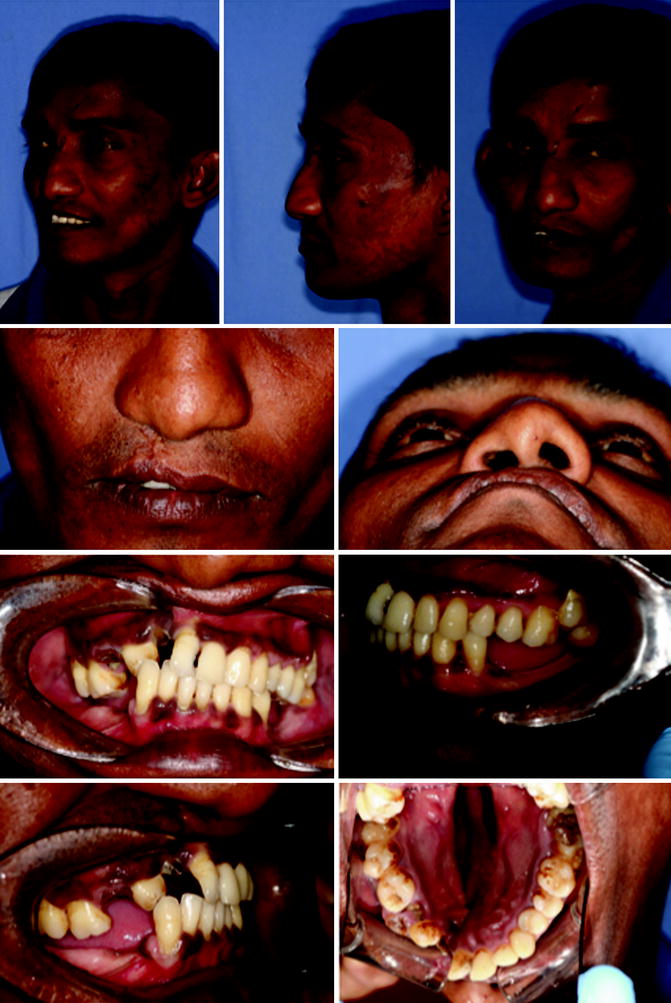

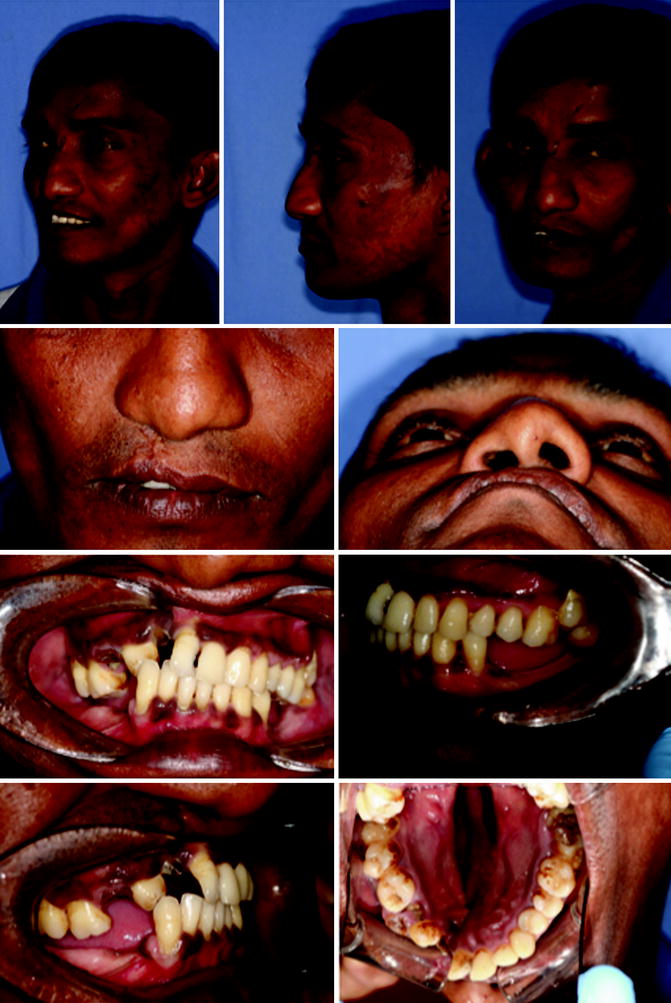

Fig. 10.1

(a–j) Illustrates a typical example of the facial appearance and dental study models of an un-operated unilateral cleft lip and palate case

10.2.2 Cephalometry

Using the Sri Lankan growth archive, Liao and Mars (2005a) studied the long-term effects of clefts on craniofacial morphology in patients with UCLP. Employing a retrospective case–control study design, they compared 30 un-operated adult UCLP patients with 52 normal (non-cleft) control subjects of the same ethnic background. Cephalometric analysis confirmed the presence of morphological differences between UCLP and non-cleft patients (Fig. 10.2). The adverse effects of clefting were predominantly on the vertical development of the maxilla both anteriorly and posteriorly and to a lesser extent on the anteroposterior development of the basal maxilla. In addition, there were differences in the position and shape of the mandible and the position of the maxillary and mandibular incisors. However, the overall anteroposterior dimensions of the maxilla were not affected by clefting, and these patients did not exhibit maxillary retrusion.

Fig. 10.2

Dental and skeletal effects of lip surgery (Liao and Mars 2005a)

10.2.3 Study Model Analysis

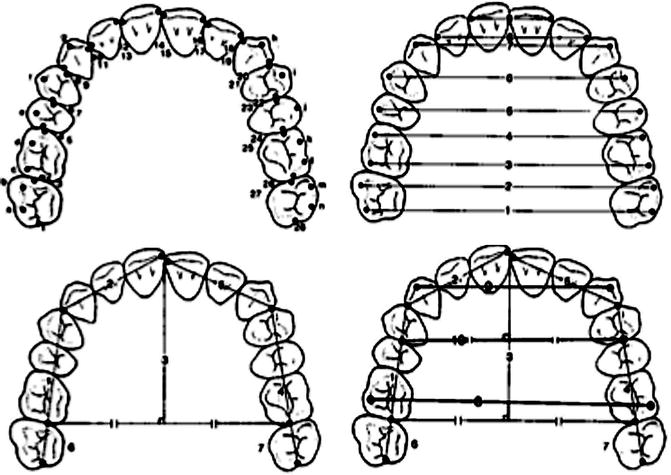

Using the reflex microscope, McCance et al. (1990) studied the maxillary arch form of 41 adults with un-operated complete unilateral cleft lip and palate and compared them to a control group of 100 normal adults (Fig. 10.3).

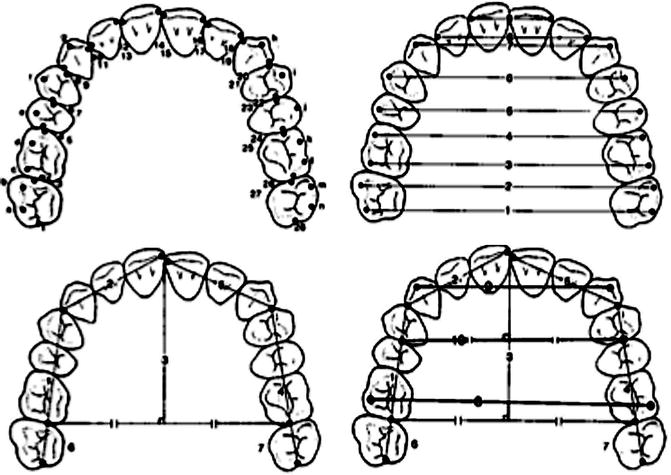

Fig. 10.3

The digitised points, chord lengths and arch widths used in the reflex microscopic analysis of study models

The teeth in the cleft group were smaller than their equivalents in the control group, the most marked difference being found in the central and lateral incisors. Arch widths of the cleft groups were reduced, more anteriorly (5 mm in the canine region) than posteriorly (1.6 mm in the second molar region), resulting in more V-shaped arches. No differences were found in the arch length or chord lengths between the groups. There was a higher prevalence of crossbites in the cleft group, 19.5 %, compared to none of the controls, and the overjet was greater in the cleft group (mean 8.2 mm) than in the controls (3.7 mm). A higher percentage of missing teeth, most commonly the lateral incisor teeth, was recorded in the cleft group. There was no difference in crowding between the two groups. Although the reductions in tooth size and arch width would suggest a small degree of primary hypoplasia, the differences are small.

The GOSLON yardstick is a robust and reproducible tool for categorising dental arch relationships into five distinct groups of increasing deformity (Mars and Plint 1985, Mars et al. 1987). It was applied to 51 un-operated UCLP cases, and the results showed 98 % of the cases were in groups 1 and 2 (excellent or very good arch relationships) and no cases in groups 4 or 5 (Fig. 10.4). In contrast, only a small proportion of operated patients were in group 1 when UK centres were assessed as part of the CSAG study (Clinical Standards Advisory Group 1998) (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.4

GOSLON grouping of UCLP patients operated by Sri-Lankan surgeons using Wardill-Kilner (Mars and Houston 1990)

Fig. 10.5

GOSLON for the 1998 CSAG (Clinical Standards Advisory Group) for the whole of the UK

10.2.4 Summary

Studies using cephalometry and study models confirm that there is an intrinsic potential for un-operated UCLP patients to grow relatively normally with minor distortions around the cleft site itself where the dentition is unrestrained because of the disrupted musculature. In addition, the lack of continuity of the arch probably explains the transverse distortions seen in the dental arch. There is a small degree of hypoplasia as discussed above but these are minor and do not account for the gross maxillary retrusion frequently reported in surgically repaired patients.

10.3 Effect of Primary Surgery on Facial Growth

It is widely accepted that facial growth and morphology in cleft lip and palate patients is abnormal, with mid-face retrusion common in patients who have had corrective surgery in infancy (Ross 1987; Semb 1991).

Historically, the cause of this mid-face retrusion has been attributed to three possible causes: an intrinsic developmental deficiency, functional distortions affecting growth and iatrogenic factors due to surgical treatment. There has been significant controversy on the extent and relative contributory role of each of these possible causative factors. It was this unresolved conflict of opinions on the aetiology of facial growth distortion in operated cleft lip and palate patients that led to the establishment of the SLCLPP.

A number of seminal papers on facial growth in cleft patients have been published from the Sri Lankan archives.

Mars and Houston (1990) reported the effects of primary lip and palate surgery on craniofacial growth in cleft patients using a cohort of Sri Lankan male patients. The studied patients were divided into three subgroups and compared to a control group of healthy males using lateral cephalometry and study model analysis. The three subgroups analysed included: those who had totally unrepaired cleft lip and palate, those who received lip repair in infancy but not palatal repair and those who had lip and palate repair in infancy. From this preliminary study, it was clearly evident that un-operated cleft patients had the potential to grow normally. Furthermore, in patients who have had a lip repair but no palate repair, the maxilla appears to also grow relatively normally.

In addition to cephalometry, Mars and Houston (1990) applied the GOSLON yardstick to the same cohort of patients aged 13 years old operated by Sri Lankan surgeons. Figure 10.4 shows that all the subjects in the totally un-operated subgroup had excellent dental arch relationships (groups 1 and 2). In the lip only subgroup, almost two thirds of the subject scored in groups 1 and 2, and only a small proportion scored in groups 4 and 5. This contrasts markedly with the lip and palate subgroup where two thirds of the patients were in groups 4 and 5 (poor dental arch relationship) and only a small proportion in groups 1 and 2.

Using preliminary data from the SLCLPP, Mars and Houston (1990) clearly showed the detrimental effects of primary palatal surgery on facial growth.

We now have complete data for 198 UCLP subjects who are greater than 20 years of age. This chapter studies the GOSLON yardstick analysis of all these patients and the cephalometric measures for 154 subjects.

10.3.1 Lip Surgery

Whilst studies on un-operated cleft patients have demonstrated the iatrogenic effects of primary cleft surgery on facial growth, there has been controversy as to whether the lip or the palate repair has the most detrimental effect on maxillary growth (Muir 1986; Mars and Houston 1990; Bardach et al. 1984).

10.3.1.1 Cephalometry

Liao and Mars (2005b) further clarified the long-term effects of lip surgery on craniofacial growth. Using lateral cephalograms from the longitudinal growth data obtained from the SLCLPP, they studied 71 adult patients, 23 non-syndromic un-operated UCLP patients and 48 non-sydromic UCLP patients who had undergone lip repair only. This study demonstrated that the major effect of the lip repair was on the anteroposterior and vertical position of the maxillary alveolus and the maxillary incisors. Furthermore, there was a differential influence from the tip of the alveolus and the incisal edge to the base of the alveolus and the incisal apex. This was associated with uprighting of the maxillary incisor and resulted in a decreased overjet and increased overbite in the lip repair only group (Fig. 10.6). The pressure of the lip thus produces secondary bone resorption in the base of the anterior maxillary alveolus.

Fig. 10.6

Effects of Lip Surgery (Liao and Mars 2005b)

10.3.1.2 Study Model Analysis

More recently, the authors carried out a review of the SLCLPP archive using the GOSLON yardstick. All patients were operated within the project and are now adults aged over 20 years and have completed facial growth. The subjects were divided into the same three subgroups as reported by Mars and Houston (1990) and had had their surgery at varying ages. Interestingly, the same results were replicated. Figure 10.7 below is almost a replica of Fig. 10.4 above.

Fig. 10.7

The diagonal line demonstrates the progressively worsening effect from no surgery to lip surgery to lip and palate surgery

Both GOSLON figures (Figs. 10.4 and 10.7) clearly demonstrate that surgery to the lip only has some effect, but this is mainly dentoalveolar. The most obvious difference is seen in the patients who have undergone both lip and palate repair, clearly suggesting that the palate repair has the most significant influence on future facial growth.

Muthusamy (1998) analysed study models of 26 patients pre and post lip repair using the reflex microscope. These patients had not had any other surgical interventions and were operated on by British surgeons as part of the SLCLPP.

The patients were divided into two subgroups – young being those who had the lip repair prepubertally (15 patients) and mature being those who had it post-pubertally (11 patients).

He found that in both groups, there was a significant reduction in arch width with the greatest reduction in the inter-canine distance. Interestingly, in the younger group, there was a reduction in arch width in all measures (anterior and posterior), whereas in the mature group, there was no significant reduction in the inter-molar and inter-premolar.

After the lip repair, there was a reduction in overjet and an increase in overbite in both groups (Fig. 10.8).

Fig. 10.8

An adult patient who had a lip repair but no palate repair demonstrating the localised effects of lip surgery

10.3.1.3 Summary

Both the cephalometric and study model studies confirm that that lip repair primarily produces a localised bone-bending effect on the anterior maxillary alveolus (alveolar moulding) and does not have a significant effect on maxillary growth.

10.3.2 Palate Surgery

Gillies and Fry (1921) were the first to suggest that the palate repair has a detrimental effect on facial growth. Interestingly, they were also the pioneers for the policy of delayed hard palate closure. The SLCLPP has been key in demonstrating the relative effects of lip and palate surgery on future facial growth.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses