Trauma management

Angus C Cameron, Richard P Widmer, Paul Abbott, Andrew A C Heggie and Sarah Raphael

Introduction

The management of dentoalveolar trauma in children is distressing for both the child and the parent (Figure 9.1), and often difficult for the dentist. However, trauma is one of the most common presentations of young children to a paediatric dentist. The patient’s emergency must be the dentist’s routine. The child should be carefully assessed regarding treatment needs before commenting to parents because many cases are not as bad as they first appear. Initial reassurance to both parent and child is of great value. Trauma not only compromises a previously healthy dentition but may also leave a deficit that affects the self-esteem and quality of life, and it commits the patient to lifelong dental maintenance.

Guidelines for management of dental injuries

The International Association of Dental Traumatology published guidelines in 2007 with recommendations for the management of dental injuries based on a review of the literature and consensus opinions. These guidelines provide views on care based on the published evidence and the opinions of professionals who practise in this field. As is stated in the guidelines, there is no guarantee of success and as further research is published, clearly the recommendations in these guidelines will be updated. The practitioner should be aware that clinical judgement is still required, depending on the presentation of each case. An internet-based set of guidelines has also been developed and sponsored by the International Association for Dental Traumatology (www.dentaltraumaguide.org). This is a free website that practitioners can use to quickly and easily access information about how to manage dental injuries, the prognosis of the teeth and many other details.

Aetiology

Most injuries are caused by falls and play accidents. Luxation injuries to upper anterior teeth predominate in toddlers because of their frequent falls during play and attempts at walking. Injuries are generally more common in boys. Blunt trauma tends to cause greater damage to the soft tissues and supporting structures, whereas high-velocity or sharp injuries cause luxations and fractures of the teeth.

Predisposing factors

• Class II division 1 malocclusion.

• Overjet 3–6 mm – double the frequency of trauma to incisor teeth compared with 0–3 mm overjet.

• Overjet >6 mm – three-fold increase in the risk.

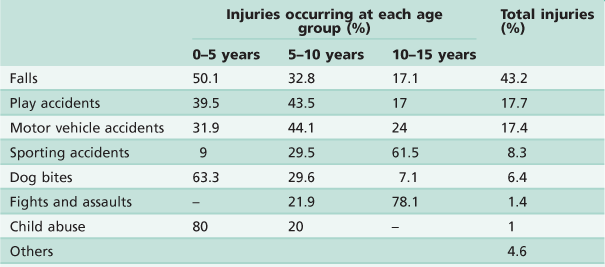

• The study summarized in Table 9.1 by Hall (1994), from the Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, shows that falls and play accidents account for the majority of injuries. Lam and others (2008) also reported that dental trauma in an Australian rural population was most frequently the result of falls, accidents while playing and while participating in sports. Importantly, although accounting for only 1% of all injuries, over 80% of child abuse occurs in the very young child.

Frequency

• 22% of children suffer trauma to the permanent dentition by the age of 14 years.

• Male : female ratio is 2 : 1.

• Peak incidence is at 2–4 years and rises again at 8–10 years.

Dog bites account for a significant number of injuries and every year several children are killed by dogs. It is common that the dog is known to the child and it cannot be stressed too highly that children must be supervised when around even the most timid of animals.

Child abuse

Child abuse is defined as those acts or omissions of care that deprive a child of the opportunity to fully develop his or her unique potential as a person either physically, socially or emotionally. There are four types of child abuse:

Dental neglect is the knowing failure of a parent or guardian to access treatment of orofacial conditions for a child. When left untreated, such conditions may adversely affect a child’s normal growth and development.

The true incidence of child abuse and neglect is unknown, and although there is increasing awareness and reporting, professionals are still reluctant to deal with it. The first step in preventing abuse is recognition and reporting. Dentists are in a strategic position to recognize and report mistreated children because they often see the child and parent/caretaker interacting during multiple visits and over a long period of time.

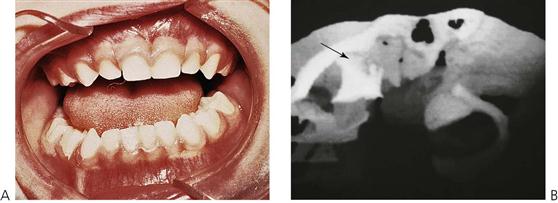

The orofacial region is commonly traumatized during episodes of child abuse (Figure 9.2). Injuries that do not match the given history, bruising of soft tissue not overlying bony prominences or injury that takes the shape of a recognizable object, and multiple injuries of different ages, may be the result of non-accidental trauma. Bite marks in children represent child abuse until proven otherwise. The characteristics and diagnostic findings of child abuse, and the protocol of reporting such cases, should be familiar to the dentist so that appropriate notification, treatment and prevention of further injury can be instituted.

Whenever injuries are inconsistent with the history, the patient must be investigated for abuse. There is a legal obligation in some countries or states to report the suspicion of child abuse or sexual assault. In Australia, child abuse teams are available at all paediatric hospitals or through the departments of family and community services.

History

As dental injuries may become the subject of litigation or insurance claims, a thorough history and examination is mandatory. Where possible, injuries should be photographed. An accurate history gives important information regarding:

Examination

Examination should be undertaken in a logical order. It is important to examine the whole body, as the patient may present first to the dentist and other injuries may also have occurred (Figure 9.3 and see Chapter 1).

Trauma examination and records

Assessment of cranial nerves involved in facial trauma

| I | Olfactory | Olfaction |

| II | Optic | Vision |

| III | Oculomotor | Movements of the globe |

| IV | Trochlear | Superior rectus |

| V | Trigeminal | Muscles of mastication |

| VI | Abducent | Lateral rectus |

| VII | Facial | Muscles of facial expression |

| VIII | Vestibulocochlear | Hearing and balance |

| IX–XII | Hypoglossal | Tongue, pharyngeal and shoulder function |

Head injury

Closed head injury is the most common cause of childhood mortality in accidents. Between 25% and 50% of all accidents in children aged up to 14 years involve the head. If there is any suggestion that a head injury has been sustained, the child should be immediately medically assessed, preferably in a paediatric casualty department.

Signs of closed head injury

• Altered or loss of consciousness.

• Bleeding from the head or ears.

Dentoalveolar injuries may take second place if there is central nervous system involvement. As a head injury may be long-lasting, initial management and replantation may be possible in consultation with other medical practitioners. If there is any loss of consciousness, hourly neurological observations should be commenced. The Glasgow Coma Scale is commonly used in Accident and Emergency departments to assess the severity of head injury and prognosis (see Appendix H).

Investigations

Radiographs

The request for radiographs should only be made after a thorough history and clinical examination. There is great value in using extra-oral films in young children, e.g. panoramic radiographs. In the very upset or difficult child, it may be the only way that some clinical information can be gained in the acute phase of management.

When taking intra-oral radiographs, several periapical images from different angulations should be taken for each traumatized tooth, plus an occlusal radiograph. These are especially important to determine the presence of root fractures and tooth luxations. As a baseline, all traumatized teeth should be radiographed to assess:

Guide to prescription of radiographs

Dentoalveolar injuries

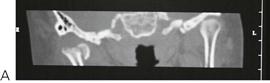

Condylar fracture (Figure 9.5)

Mandibular fracture

Maxillary fractures

• CT scan.

New imaging technologies have superseded older-style views such as the lateral oblique, the reverse Townes’ and Waters’ (occipitomental 30°) projections. While such radiographs may be valuable in particular cases, contemporary practice indicates the use of fine-slice CT or cone-beam tomography for an accurate assessment of middle third fractures in children.

Pulp sensibility tests

Pulp sensibility tests provide an essential baseline measure of the pulp status. It is common that the initial responses at presentation may be inaccurate; however, it is important that results are recorded for later comparison. The results of pulp sensibility tests performed immediately following trauma are also very useful predictors of the prognosis of traumatized teeth. Teeth that do respond to these tests are more likely to recover than teeth that do not respond. Young children often find it difficult to discriminate between the touch of the tester and the actual stimulus itself, so the clinician must be aware of the possibility of false results. In cases that are difficult to diagnose, isolation of individual teeth under rubber dam may be required.

Pulp sensibility tests are used to help assess the status of the pulp. Previously and erroneously termed ‘vitality tests’, the contemporary terminology (i.e. sensibility tests) stresses the fact that the neural and vascular components of the pulp tissue need individual consideration. Sensibility is defined as the ‘ability to respond to a stimulus’ – which is what is tested with thermal and electric pulp tests. It is important to understand that a tooth may not respond to a thermal or electric pulp test but it may still have an intact blood supply. Such discrimination of the health of the pulp is important in planning treatment.

Thermal pulp tests

Responses to cold stimuli give the most reliable and accurate results in children (even with immature teeth). The carbon dioxide (dry ice) pencil is regarded as the most convenient. Cold sprays may also be used but they are not as accurate or as reliable. Cold tests have the advantage that assessment of the pulp is possible while temporary crowns and splints are in place.

Electric pulp tests

Electric pulp tests may give a graded response to stimuli. When using these instruments, the current should be slowly increased so that sudden painful stimulation of the tooth is avoided.

Percussion

There are two reasons to percuss teeth:

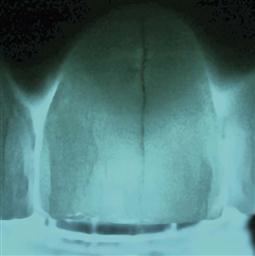

Transillumination (Figure 9.6)

This is an extremely useful, non-invasive technique to assess the presence of cracks and/or fractures, and subtle alterations in crown colour which may indicate a change in the pulp status.

Other considerations in trauma management

Having carefully assessed the patient, the only treatment necessary may be to reassure the child and parent, and to discuss the various possible sequelae such as pulp necrosis, resorption, infection and facial swelling.

Fasting requirements

If the patient requires extensive work under general anaesthesia, it is important to check fasting details. A child over 6 years of age must be fasted for at least 6 hours without solids or liquids. Children under the age of 6 years must be fasted for 6 hours without solids and 2 hours without liquids.

Immunizations

If a child has sustained an injury that involves contamination of the wound with soil, especially from a farm area, their tetanus immunization status must be determined. If the child has completed their normal immunization schedule, under normal circumstances boosters are not required.

Maxillofacial injuries

Fractures of the facial bones are uncommon in children and account for less than 5% of all maxillofacial fractures. Consequently, few surgeons have extensive experience in this area and the management of these cases must embody an understanding of the implications of such injuries for the growing child (Figure 9.7).

Principles of management

Management of maxillofacial trauma is complicated in a child by the unerupted dentition, anxiety, growth considerations and the common association of closed head injuries that may delay definitive treatment. The use of internal fixation such as mini-plates and screws must be undertaken with care due to the potential for damaging developing tooth buds. Intermaxillary fixation, occasionally in conjunction with trans-osseous wires is well tolerated in children. While arch bars may be used as dental fixation, silver cap splints may be still used effectively. With accurate reduction, fixation and immobilization, fractures unite within 3 weeks. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment and strict oral care must be maintained. Non-union or fibrous union is rare.

Fractured mandible

Most mandibular fractures involve the parasymphysial region (due to the position of the unerupted canine) and the condylar neck either in isolation or in combination.

Clinical signs

Condylar fractures

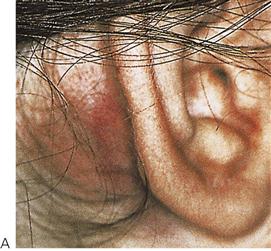

Fractures of the mandibular condyle are likely to be under-diagnosed in children and comprise up to two-thirds of all mandibular injuries. This injury usually results from trauma to the lower border of the chin. If a subcondylar fracture occurs, the condylar head is usually displaced antero-medially by the action of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Depending on the displacement of the fragments and the compensatory posturing of the mandible, there may be deviation of the chin to the affected side or there may be no occlusal disharmony. Bleeding from the external meatus may occur due to perforation of the anterior wall of the auditory canal by the condylar head (see Figure 9.7C,D). Bleeding or discharge from the ear should be investigated by an otolaryngologist but suctioning of the external meatus is contraindicated due to the potential for disturbance of the ossicular chain should there be a perforation of the tympanic membrane. Displacement of the condylar head into the middle cranial fossa has been reported but is a rare event.

Management

Treatment is almost always conservative with a short period of rest followed by active movement to prevent temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Fractures involving telescoping of the condyle and distal fragment may be successfully treated with functional appliances for 2–3 weeks or longer, allowing better remodelling. Bilateral subcondylar fractures may result in significant displacement and an anterior open bite. A short period of intermaxillary fixation with posterior bite blocks to distract the fragments may be indicated where there has been gross displacement of the condylarhead, or in severe cases of bilateral condylar fracture.

As the condylar neck is relatively broader in the child with a greater volume of cancellous bone, fractures of the articular surface are more common than in the adult. In cases of intracapsular fracture (Figures 9.5, 9.9), follow-up over many years will enable detection of any growth disturbance. Should there be a limitation of opening or frank ankylosis, early intervention to mobilize and reconstruct the mandible is recommended.

Maxillary fractures

Middle-third fractures are rare in children and usually present with other severe cranio-maxillofacial and head injuries. Mid-facial fractures tend not to follow the typical ‘Le Fort lines’, as the immature skeleton results in more greenstick and incomplete fractures.

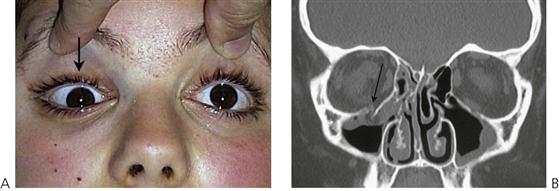

Orbital floor ‘blow-out’ and orbital roof ‘blow-in’ are seen and may require urgent reduction, particularly where orbital contents, such as fascia and muscle are trapped, thus preventing normal ocular movements.

Clinical signs

• Facial swelling and periorbital ecchymosis (Figure 9.10).

• Periorbital surgical emphysema.

• Subconjunctival haemorrhage, with no posterior limit.

• Nausea, vomiting and photophobia often occurs with inferior rectus muscle entrapment.

• Orbital rim contour deformaties.

• Infraorbital paraesthesia (Figure 9.11).

Sequelae of fractures of the jaws in children

Closed head injury

Children who sustain middle-third facial injuries usually have concomitant head injuries. Head injuries occur in 25% of cases of facial trauma. These children spend extended periods in intensive care units, may undergo personality changes, suffer post-traumatic amnesia and may have episodes of neuropathological chewing.

Tooth loss

Approximately 10% of children who sustain fractures of the jaws will also have loss of permanent teeth.

Developmental defects of enamel

In addition to the damage caused by displacement of primary teeth into the crypts of permanent successors (see ‘Sequelae of trauma to primary teeth’ later in the chapter), unerupted teeth in the line of jaw fractures may also be damaged. Defects may include:

Intra-articular damage to the temporomandibular joint

There is always a risk of ankylosis of the temporomandibular joint after significant displacement of the condylar head, intracapsular fracture or a failure to achieve early mobilization of the joint. Treatment of the ankylosis involves condylectomy and joint reconstruction with a costochondral graft in later childhood.

Growth retardation

Maxillary (Figure 9.12) and mandibular growth retardation may occur following major trauma. Significant scarring of soft tissues and/or tissue loss may inhibit jaw growth. Mandibular asymmetry with antegonial notching may occur on the affected side after subcondylar fracture. The key to management is to correct asymmetries early to avoid secondary maxillary deformity.

Luxations in the primary dentition

General management considerations

There is general agreement that most injuries to the primary dentition can be managed conservatively and heal without sequelae. As a general rule, either leave and observe or extract the tooth.

Immunization

If the child is not fully immunized then a tetanus booster is required: tetanus toxoid 0.5 mL by intramuscular injection.

Antibiotics

Unless there are significant soft-tissue or dentoalveolar injuries, antibiotics are not usually required. Antibiotics are prescribed empirically as a prophylaxis against infection, but they are not a substitute for proper debridement of wounds. All drugs should be prescribed according to the child’s weight (see Appendix E).

Luxations

Up to 2 years of age, the most common injuries to the primary teeth are luxations involving displacement of the teeth in the alveolar bone.

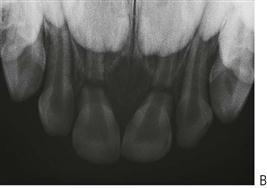

Concussion and subluxation (Figure 9.13)

Concussion is an injury to the tooth and ligament without displacement or mobility of the tooth. Subluxation occurs when the tooth is mobile but is not displaced. Both involve minor damage to the periodontal ligament. Teeth with these injuries will be tender to percussion. There will be haemorrhage and oedema within the ligament, but gingival bleeding and mobility only occurs if the teeth have been subluxated.

Intrusive luxation

Intrusive injuries (Figure 9.14) are the most common injuries to upper primary incisors. Newly erupted incisors often take the full force of any fall in a toddler. There is usually a palatal and superior displacement of the crown, which means that the apex of the tooth is forced away from the permanent follicle.

Extrusive and lateral luxation (Figure 9.15)

Treatment is dependent on the mobility and extent of displacement. If there is excessive mobility the tooth should be extracted.

Fractures of primary incisors

Crown fractures not involving the pulp (Figure 9.17A)

Unlike the permanent dentition, primary teeth are more commonly displaced rather than fractured. Enamel and dentine fractures may be smoothed with a disc and, if possible, cover the dentine with glass ionomer cement or composite resin. Paediatric strip crowns are often useful. A possible sequel is pulp necrosis and/or grey discolouration. If the pulp does become necrotic, then it may subsequently become infected, leading to an apical abscess.

Complicated crown/root fractures (Figure 9.17C–E)

More commonly, fractures of primary teeth involve the pulp and extend below the gingival margin. Commonly, there are multiple fractures in individual teeth. In these cases, it is not feasible to adequately restore the tooth and therefore it should be extracted. Often the fracture is not immediately evident, but the child may present several days after the trauma with a pulp polyp which is causing separation of the fragments. Such a proliferative response is a protective mechanism and is not painful. Management of such a case should be by extraction of the tooth.

Management

Root fractures (Figure 9.16B)

As mentioned above, when children fracture primary incisors, there is usually a complex crown/root fracture that extends below the gingival margin and extraction is indicated. Isolated root fractures are uncommon. Normally, no treatment is necessary for primary incisors with horizontal or transverse root fractures. If, at regular review, the pulp shows signs of necrosis and infection, with excessive mobility or sinus formation, the coronal portion should be extracted. The apical root fragments are usually removed by resorption as the permanent tooth erupts.

Dentoalveolar fracture (Figure 9.17F)

This is more common in the mandible with the anterior teeth being displaced anteriorly with the labial alveolar cortical plate. It is often desirable to reposition the teeth with the bone to maintain the alveolar contour. This can be achieved with a thick nylon suture (2–0) passed through the labial and lingual plates of the bone. Teeth that are excessively mobile should be carefully dissected out of the sockets preserving the labial plate, which is then repositioned and sutured.

Sequelae of trauma to primary teeth (Figures 9.18, 9.20)

It is important to discuss with parents the sequelae of luxated or avulsed primary incisors. Although it may be difficult to accurately predict the prognosis for the unerupted permanent teeth, parents appreciate having an idea of the possible outcomes. In cases that have been followed up in studies, up to 25% of children are left with some developmental disturbance of the permanent tooth.

Damage to the unerupted permanent dentition occurs more often with intrusive luxation and avulsion in very young children. It is important to warn parents of possible problems with permanent teeth and also to reassure them that, with modern restorative materials, minor defects are easily repaired. Sequelae in the permanent dentition depend on:

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses