Systemic Factors Influencing Periodontal Diseases

• Understand systemic factors that influence dental hygiene care.

• Describe conditions that require consultation with a patient’s physician.

• Describe changes in oral tissues observed with systemic diseases and conditions.

• List modifications needed for optimal treatment of patients with systemic conditions.

Cardiovascular Diseases

Hypertension (High Blood Pressure)

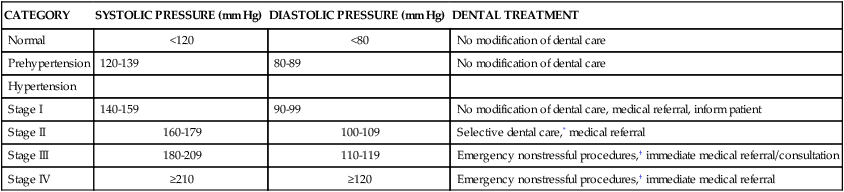

High blood pressure is a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and kidney failure. Tens of millions of people in the United States have high blood pressure or are taking antihypertensive medications.1 Hypertension has been called the “silent killer” because it is frequently asymptomatic and more than half of patients with hypertension are unaware that they have it. The prevalence of the disease increases dramatically with age,2 and variations also occur by gender and race.3 Blood pressure is the force of the blood pushing against the walls of arteries. It is highest when the heart beats (systolic pressure) and lowest when the heart is resting (diastolic pressure). Blood pressure is recorded as two numbers, the systolic over the diastolic pressure (e.g., 110/70 mm Hg).4 In general, patients with readings greater than 140/90 mm Hg are considered to be hypertensive.5,6 Patients with a systolic pressure from 120 to 139 mm Hg and a diastolic pressure from 80 to 89 mm Hg are considered to have prehypertension.4 Table 9-1 shows a classification of hypertension from the Joint National Committee on the Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.5

TABLE 9-1

Classification of Adult Blood Pressure and Dental Treatment Modifications

| CATEGORY | SYSTOLIC PRESSURE (mm Hg) | DIASTOLIC PRESSURE (mm Hg) | DENTAL TREATMENT |

| Normal | <120 | <80 | No modification of dental care |

| Prehypertension | 120-139 | 80-89 | No modification of dental care |

| Hypertension | |||

| Stage I | 140-159 | 90-99 | No modification of dental care, medical referral, inform patient |

| Stage II | 160-179 | 100-109 | Selective dental care,* medical referral |

| Stage III | 180-209 | 110-119 | Emergency nonstressful procedures,† immediate medical referral/consultation |

| Stage IV | ≥210 | ≥120 | Emergency nonstressful procedures,† immediate medical referral |

See: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/.

*Selective dental care may include, but is not limited to, dental prophylaxis, nonsurgical periodontal therapy, restorative procedures, and nonsurgical endodontic therapy.

†Emergency nonstressful procedures may include, but are not limited to, dental procedures that may help alleviate pain, infection, or masticatory dysfunction. These procedures should have limited physiologic and psychological effects. An example of an emergency nonstressful procedure might be a simple incision and drainage of an intraoral fluctuant dental abscess. The medical benefits achieved by performing emergency nonstressful procedures in stages III and IV hypertensive patients should outweigh the risk of complications caused by the patient’s hypertensive state.

Used with permission. Modified from Muzyka BC, Glick M. The hypertensive dental patient. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:1109–1120.6 Copyright 1997, American Dental Association.)

The use of epinephrine-containing local anesthetics is not contraindicated in patients with well-controlled hypertension. However, it is advisable to use minimal amounts of epinephrine, such as 0.04 mg per dental visit (approximately two cartridges containing 1 : 1000,000 parts epinephrine). If pain is anticipated in association with the planned dental or periodontal treatment, very good local anesthesia is desirable to minimize the release of endogenous epinephrine.7,8

Coronary Artery (Ischemic Heart) Disease

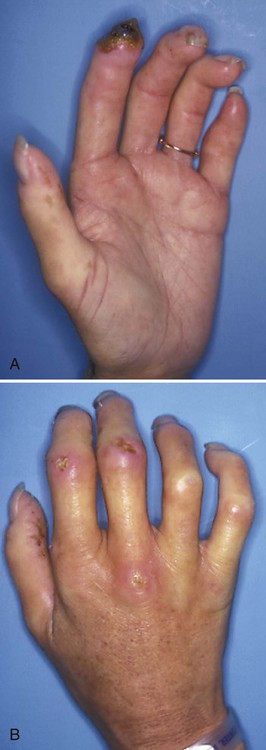

A condition in which anginal pain is predictable and controlled by medication is called stable angina.9 Patients with stable angina frequently control their anginal pain by taking one or more of the following types of drugs: nitrates (e.g., nitroglycerin), beta-adrenergic blockers, and calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine). Gingival enlargement is one of the common side effects of nifedipine (Procardia) and some other calcium channel blockers.10–14 The gingival enlargement can make oral hygiene difficult and thereby increase the risk of plaque-induced diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal disease, (Figure 9-1).

Patients with stable angina can safely receive routine dental care, but it is advisable to minimize stress by scheduling relatively short morning appointments so that the patient is well rested. As with hypertensive patients, local anesthesia should be used for potentially painful procedures to minimize the release of endogenous epinephrine.7,8 If an anginal attack occurs during the delivery of dental care, treatment should be discontinued, the patient should be placed in a semisupine position, and standard emergency procedures should be performed.

Diseases of Heart Valves

Any dental or periodontal procedure that introduces bacteria into the bloodstream of patients with heart valve disease can increase their risk of a potentially fatal heart infection called infective endocarditis. In general, damaged heart valves are more susceptible to colonization by bacteria. In addition, the stasis of blood, frequently associated with defective heart valves, increases the likelihood that bacteria will be able to attach successfully to fibrin deposits that can form on the heart at sites at which blood flow is impaired. In the past, some patients with heart valve problems were prescribed antibiotics before undergoing any procedures in which gingival bleeding might be induced, including periodontal examination and scaling of the teeth. It was believed that the antibiotics lowered the risk of developing infective endocarditis. However, this is no longer routinely recommended because the risks of taking antibiotics often outweigh the risk of developing infective endocarditis.15

Acquired heart valve disease is often found in patients with a history of rheumatic fever16 and several other systemic diseases.17–19 Rheumatic fever is an acute systemic inflammatory disease that sometimes follows throat infections with group A streptococci. Antistreptococcal antibodies that form in response to these infections can react with heart valve tissues and cause inflammation and damage to the valves. This damage may lead to rheumatic heart disease in which there is scarring of the heart valves. In the past, a history of rheumatic heart disease was one of the conditions for which antibiotics were routinely prescribed in an attempt to reduce the risk of infective endocarditis. Other conditions for which preoperative antibiotics are no longer recommended include mitral valve prolapse, bicuspid valve disease, calcified aortic stenosis, and some congenital heart conditions such as ventricular or atrial septal defects.15 The American Heart Association (AHA) has published guidelines on when antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures are recommended (Table 9-2).15 However, before performing dental procedures (including oral examinations with periodontal probing or exploring) in a patient with a history of heart valve problems, the clinician should consult the patient’s physician to determine whether preoperative coverage with antibiotics is necessary.

Cardiac Arrhythmias

Dental procedures can be safely performed in most patients who are under medical treatment for cardiac arrhythmias. However, patients who are taking antiarrhythmic drugs can experience a variety of side effects that may complicate or worsen their dental and periodontal problems. For example, some antiarrhythmic drugs, such as disopyramide (Norpace), mexiletine (Mexitil), verapamil (Calan), and diltiazem (Cardizem), may lead to xerostomia, which can facilitate plaque retention and increase the patient’s susceptibility to dental caries and periodontal disease. Drugs such as phenytoin (Dilantin), verapamil, and diltiazem may lead to severe gingival enlargement, which makes plaque control difficult (see Figure 9-1). In some patients, mexiletine and quinidine (Cardioquin) may cause neutropenia (a decrease in circulating neutrophils), which can increase their susceptibility to periodontal and other infections.

Some cases of cardiac arrhythmia are best treated by surgical insertion of a battery-operated electronic device (pacemaker) under the skin of the upper chest wall. Wire leads connect the pacemaker to an electrode that is placed in contact with heart tissue. The pacemaker sends periodic electrical impulses to the heart, thereby regulating its rate of contraction. The AHA guidelines do not recommend that patients with pacemakers be given antibiotics before dental procedures.15 However, for certain patients, the physician or cardiologist might recommend antibiotic coverage.

In one type of arrhythmia, portions of the heart undergo rapid irregular twitching, referred to as fibrillation. Defibrillators are designed to send electrical impulses to the heart to shock it into a normal pattern of contraction. Defibrillators can be implanted subcutaneously in the abdomen with electrodes connected to the heart. The devices detect the onset of fibrillation and automatically send small electrical shocks to the heart to correct the situation. As with pacemakers, prophylactic antibiotic coverage is not usually required before dental procedures.15

Patients Who Are Taking Anticoagulants

Many patients with a history of cardiovascular disease take small daily doses (80 to 325 mg) of aspirin, which retards the formation of blood clots by inhibiting platelet aggregation. At these doses, aspirin does not significantly alter the bleeding time,20 and postoperative bleeding from dental hygiene procedures is usually not a problem.

Joint Diseases and Disorders

Arthritis

It is important to remember that arthritis can be the result of many systemic diseases and that it is only one of several medical problems that may have dental implications. For example, patients with progressive systemic sclerosis (PSS), or scleroderma, experience multiple dental and periodontal problems that are directly attributable to their systemic disease.21 PSS is a chronic connective tissue disease of unknown cause in which abnormal amounts of collagen are continuously deposited in a variety of organ systems, including the skin, lungs, and kidneys. PSS can cause death due to kidney or respiratory failure. As the disease progresses, the skin loses much of its elasticity and becomes almost leather-like. Severe arthritis and stiffening of the hands are common (Figure 9-2). It is difficult for these patients to hold or manipulate plaque control devices, and their firm inflexible skin often prevents them from opening their mouths wide enough to allow the dentist or dental hygienist access to perform routine procedures. As a result, patients with PSS tend to experience high rates of dental caries and periodontal disease. Significant gingival recession is a common feature (Figure 9-3). An unusual oral finding in some patients with PSS is the uniform widening of the periodontal ligament space seen in radiographs (Figure 9-4).22 Although PSS is not a common disease, it is a dramatic example of a systemic disease that can present challenges to the dentist and dental hygienist in providing adequate oral health care.

Artificial Joints

In some patients with arthritis, the destruction of joint tissues can result in severe pain and loss of function. In such cases, it is often necessary to replace the affected joint with an artificial or prosthetic device. Through modern orthopedic surgery, it is possible to replace joints of the hip, knee, elbow, wrist, and shoulder. Complete replacement of the hip joint is the most common procedure. Insertion of an artificial knee joint is often performed. Because more than 450,000 joint prostheses are placed annually in the United States, most dental practices will encounter patients with these devices.23

Infection, in one form or another, occurs in approximately 1% of joint prostheses and is a major cause of their failure.24 The sources of infections of joint prostheses (infections that occur more than 3 months after joint placement) are not known, but bacteremias originating from acute dental, respiratory tract, dermatologic, or urinary tract infections are prime suspects.24–28 It appears that the highest risk of late infections of joint prostheses is up to 2 years after joint replacement.29

All patients with total joint replacements, orthopedic pins, and plates do not routinely require antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment.23 However, some patients may be at increased risk of hematogenous joint infection and should be considered as candidates for antibiotic coverage before extensive bacteremia-producing dental procedures. Guidelines for antibiotic regimens for these patients are currently being revised. Because there are no universally approved antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines, it is recommended that the patient’s physician be consulted prior to performing dental hygiene procedures in an individual with artificial joints.

Endocrine Disturbances and Abnormalities

Diabetes Mellitus

It is estimated that more than 16 million people in the United States have diabetes mellitus (DM), but only half of them have been diagnosed.30 Due to the obesity epidemic, the number of people with the disease is increasing. DM is a group of disorders that share the common feature of an elevated glucose level in the blood. The underlying problem in DM is an insufficient supply or impaired availability of insulin, a pancreatic hormone that is necessary for the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Based on the newest method of classification there are two main types of DM, type 1 and type 2.31 Although different groups of genes have been linked to the risk of developing of each of these two forms of diabetes, both forms have a genetic component.

Approximately 10% to 20% of all cases of diabetes mellitus are of the type 1 variety. In this form of the disease, there is a severe deficiency of insulin as a result of the destruction of pancreatic beta cells. Destruction occurs because of autoimmune reactions to beta cells that develop in response to environmental injury from some viruses.32 In other cases, destruction of beta cells may be caused by tumors, surgery, and toxic reactions to drugs or chemicals.32 Onset of the disease is usually rapid and occurs around the time of puberty. Medical control of type 1 DM requires periodic self-injection with one or more prescribed insulin preparations.

Patients with type 2 DM account for 80% to 90% of all cases of diabetes mellitus. In the early stages, the pancreatic beta cells are intact and capable of producing insulin. There are, however, two general metabolic defects associated with the development of type 2 DM, impaired secretion of insulin and insulin resistance.33 Although the precise reasons for these abnormalities are unknown, defective cell receptors for insulin are believed to play a role in insulin resistance.31 The onset of the disease is slow and it usually affects overweight individuals older than 30 years.32 The incidence of the disease increases with age. Medical control of early forms of type 2 DM can frequently be achieved by dietary modifications. If problems persist, oral hypoglycemic agents are used that stimulate insulin release from the pancreas and enhance insulin uptake by the tissues. In many patients with long-standing type 2 DM, loss of pancreatic beta cells eventually occurs, and periodic insulin injections are required to achieve medical control of the disease.

Patients with either form of diabetes suffer a wide variety of cardiovascular, kidney, eye, and neurologic problems.32 In addition, patients with uncontrolled or poorly controlled DM appear to be more susceptible to infections, including periodontal disease.33,34 The precise reasons for this increased susceptibility are unknown, but certain antibacterial functions of neutrophils appear to be abnormal.35–38 Other common oral problems associated with diabetes include asymptomatic parotid gland enlargement39 and dry mouth resulting from decreased salivary flow.40

There is a long-standing clinical impression that control of gingival inflammation through periodontal therapy and good daily oral hygiene reduces insulin requirements in patients with diabetes.41 In other words, satisfactory metabolic control of diabetes is made easier if periodontal infections are arrested. There is a growing body of scientific evidence supporting this clinical impression.42–45

Pregnancy

Increased gingival inflammation (gingivitis) is frequently associated with pregnancy.46–50 The gingivitis can be severe, with the tissues becoming swollen and red (Figure 9-5). Patients often report bleeding gums because the tissues bleed on the slightest provocation. The gingivitis is most severe during the first and second trimesters. It decreases somewhat around the eighth month and after parturition.47,48 If left untreated, the severe gingivitis associated with pregnancy may lead to the development of periodontitis, with the loss of alveolar bone and even teeth.46,50

It is not known precisely why gingival inflammation intensifies during pregnancy, but it has been clearly established that the inflammation is caused by plaque.47,48 However, vascular alterations associated with the hormonal changes of pregnancy (i.e., elevated serum levels of estrogen and progesterone) make the gingiva more susceptible to plaque-induced inflammation.50 Increased estrogen and progesterone can promote the growth of certain suspected periodontal pathogens such as Prevotella intermedia.51,52 In addition, changes in the immune system associated with pregnancy alter the host defenses against some infections.49

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses