Pain, Pain Control, and Sedation

Gro Haukali, Stefan Lundeberg, Birthe Høgsbro Østergaard, and Dorte Haubek

In clinical dentistry and medicine, pain is synonymous with significant discomfort. However, it is important to remember that pain has a necessary and purposeful function. Pain signals tissue damage, and thereby alerts the individual to take action in alleviating such damage.

Pain may be acute or chronic and associated with trauma, diseases, postoperative healing and treatment. In this chapter, the main focus will be on acute pain associated with dental procedures (procedural pain). Painful procedures experienced during childhood have proved to be one of the most important factors behind fear, anxiety and behavior management problems in connection with dental treatment (see also Chapter 6).

Pain is defined as a subjective sensory and emotional experience (Box 9.1), which may or may not be associated with tissue damage. This implies that only the child patient himself or herself can decide whether a clinical procedure is painful or not [1]. This may be difficult to understand for the dentist who will tend to relate the level of pain to the level of tissue damage. There are several reasons for this discrepancy between pain perception and tissue damage that we observe [2].

During the past 25 years, more focus has been given on children’s perception of pain in different health‐care situations, based on the fact that children’s pain has been underestimated and not sufficiently treated. It was believed that the newborn child’s central nervous system (CNS) was immature and not able to register pain as in adults. Research has, however, shown that both neonates and small children are at least as pain sensible as the adult based on less developed functions that inhibit or modify pain responses in their CNS [3]. It has also been shown that children may be hypersensitive for pain when exposed to painful stimuli in early life, particularly children with chronic diseases and those who have been critically sick. Such children may show signs of hyperalgesia, either general or local, and their behavior may be affected by it. After a painful event or trauma, a pain memory frequently develops. The pain memory has two different properties, a physiologic and an affective component, both of which have long‐term effects.

Evidence also exists that children who have experienced painful dental procedures, particularly at young ages, are more pain sensitive and display more behavioral problems during dental treatment than those who have not. The risk for this increases potentially if the painful stimuli have been experienced in combination with a feeling of lack of control. A typical clinical situation is when the child is being exposed to painful procedures under restraint (behavioral control), or when the painful stimulus comes suddenly without having prepared the child for it (informational control).

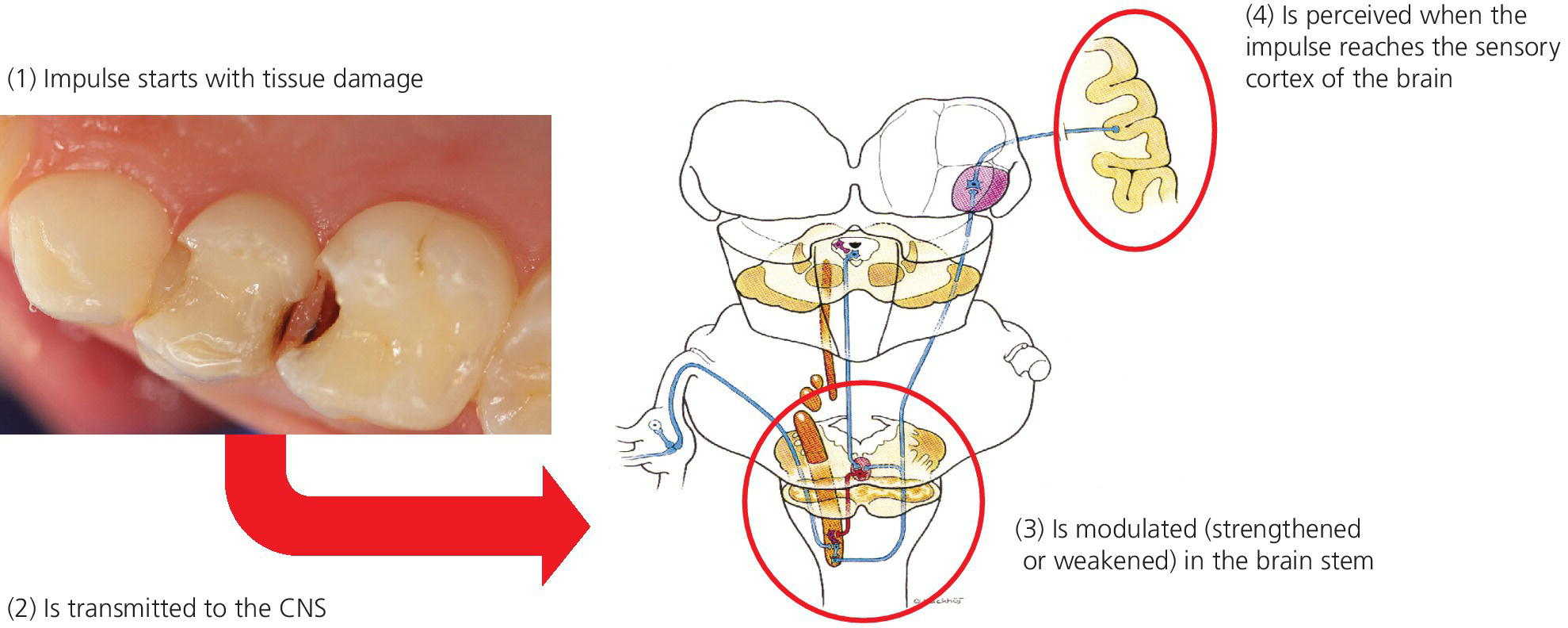

Another reason that children may perceive pain in situations without tissue damage is based on classical conditioning. If a child has undergone a painful procedure based on tissue damage (e.g., drilling into dentin) during a dental procedure, and this stimulus (unconditioned stimulus) is combined with other stimuli, such as the sound and the water spray of the drill (conditioned stimuli), it may result in pain perception when the conditioned stimuli are presented alone (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Pain perception based on classical conditioning: a painful procedure based on an unconditioned stimulus (e.g., tissue damage when drilling into dentin), combined with other stimuli such as the sound and the water spray of the drill (conditioned stimuli), may result in pain perception when the conditioned stimuli are presented alone.

There are a number of additional factors known to affect the individual perception of pain, such as peripheral and central sensitization, biological variation, previous pain experience, context, and a variety of psychological factors. The complexity of pain perception can explain the lack of correspondence between the degree of noxious stimuli and the intensity of pain experience. From the neurophysiological point of view a noxious stimulus creates both a local (peripheral) sensitization in the damaged area and changes within the CNS (central sensitization) which amplify the ingoing signaling to pain areas. This plasticity within the nervous system can alter the pain signaling for an extended time, long after healing has occurred in the affected area (physiological pain memory) [2,4]. The transmission of pain impulses does not only target the sensory cortex. A complex system with signaling from the sensory cortex as well as direct impulses from lower brain structures reaches the limbic system. The limbic system accounts for the affective reaction to a pain stimulus and plays a major part in pain perception. Previous pain experiences (psychological pain memory) and fear are two of the most important factors contributing to the affective component of pain perception.

A simplified illustration of the frequently observed lack of correspondence between the degree of tissue damage and pain reaction is illustrated in Figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2 The perception of procedural pain due to tissue damage (nociceptive pain) depends on a variety of factors, owing to the fact that the stimuli are modulated in the central part of the brain before reaching the sensory cortex. Previous pain experiences (psychological pain memory) and fear are the most important factors contributing to the affective component of pain perception.

Methods of pain control

The complexity of pain perception is a challenge for the dental practitioner when treating children. However, the prevention and alleviation of pain is a basic human right that exists regardless of age, which demands some basic principles for good clinical pain practice to be maintained in pediatric dentistry (Box 9.2).

Measuring pain is an important factor to improve care in children. The aim is to provide acceptable pain levels for the child undergoing dental treatment and therefore we as caregivers have to find ways to assess the pain experience in the individual child. Pain assessment puts pain on the treatment agenda, and can help us to identify pain under treatment and to evaluate new pain treatment strategies. Since pain is personal and subjective, age‐appropriate self‐report scales should be used when possible, e.g., visual analogue scale, faces pain scale and colored analogue scale (Box 9.3). In children with limited communication skills indirect measurement can be used as observation of behavior (e.g., behavior rating scales) and physiologic reactions (e.g., heart rate, sweating). In clinical practice, these methods must be adapted to the cognitive and linguistic skill of the individual child and be easy to use.

Both the prevention and treatment of procedural pain should be based on a preoperative judgment of factors that may be assumed to affect the child’s perception of pain. These factors may be divided into child‐centered approaches and a disease‐centered approach, and examples are given in Box 9.4.

The child‐centered approaches are based on the great plasticity of pain perception in children, meaning that environmental and psychological factors may be powerful in influencing their perception of pain. The most basic techniques are described in Chapter 6. The selection of methods should be based on a clinical judgment of how vulnerable the child may be, which must be done in collaboration with the child itself and its parents. Among factors to be taken into consideration are age and maturity, temperament, previous pain experiences, and family/social network.

The need for disease‐centered approaches must be estimated based on both the nature and extent of tissue damage and the vulnerability of the child. Robust and experienced children with ability of coping and control are able to undergo considerable dental treatment with minimal use of pharmaceutical agents. On the other hand, the vulnerable child with low coping ability and previous negative experiences with painful procedures must be taken care of by extensive use of both psychological and pharmaceutical methods.

Local analgesia

Local analgesia is an efficient and safe method for controlling pain in pediatric dental care. The rate of success, however, depends on both the technique and the operator. Some methods of injection produce minimal discomfort, as will be described in the following. Furthermore, the operator’s attitude and confidence in administrating local analgesia influence the success rate, and it has been shown that some dentists find it stressing to give a mandibular block to children below school age [5,6].

In addition to pain control, local analgesia can be used as a diagnostic tool and in the control of hemorrhage.

Preparation of the patient

Children of all ages should be given some kind of preparation before an oral injection, adapted to their age and maturity. The preparation must be preceded by establishing a good relationship between the operator and the patient and consists of giving the child a feeling of control during the situation (see Chapter 6). If the child shows signs of fear this should be dealt with before the start of the procedure. Ask the child why they experience fear and try to find solutions to their worries. It may be advisable to mention the injection in a session prior to the treatment session. In young children of 3–6 years, a simple statement that local analgesia will be used should be made along with an adjusted explanation. A more elaborated introduction can be given just prior to the injection, taking into account that the child should only be given information that he or she can handle. A young child can become more nervous when faced with too much detailed information. Whether the needle should be shown to the child before injection should also be considered from the same point of view. When the child is older (6–7 years old), he or she will be able to handle more detailed information, and the dentist has to give the child more control. It may also be necessary to teach different coping techniques, e.g., relaxation and paced breathing. However, children vary quite considerably in their coping abilities; some benefit greatly from watching and viewing every step, in other cases it is better to distract the child at the actual moment of the injection. When children develop the ability of abstract thinking at about 12 years, their reaction to pain is more like that of an adult. Most children at this age will also be able to take full responsibility for whether local analgesia should be used or not. Before that age, the dentist has the responsibility to make the decision.

Intraoral topical analgesics

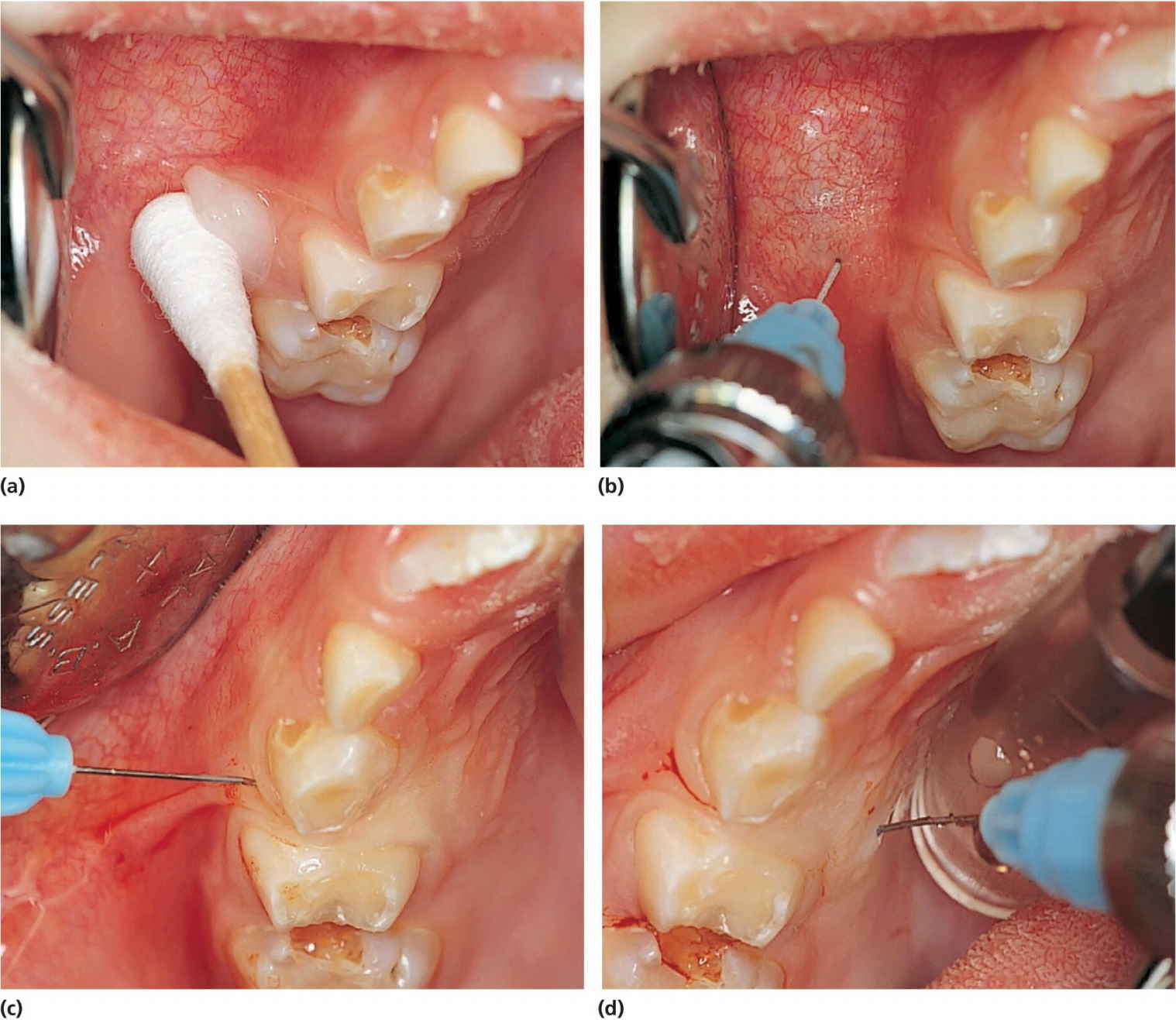

Topical local analgesic agents are extremely important in reducing pain during intraoral injections and should be used routinely. They are available as spray, gel, ointment, and solution. The most commonly used are lidocaine (5 or 20%) and benzocaine (20%) as ointment or gel. Topical analgesic agents will anesthetize the surface tissue to a depth of 2–3 mm, if used properly. The ointment or gel is applied on dry mucosa for 2–5 minutes depending on the concentration of the agent. For many children the use of topical analgesics will be connected with their first experience of intraoral pain control, and it is of great importance that it is given sufficient time to be effective. The child must also be informed about the strong taste of the agent. The application is most practically made with a cotton bud over a limited area. It is important to limit the amount used (Figure 9.3a). The uptake from the mucosa is rapid, and it is important to remember that the concentration of the active agent in the topical solution often is high.

Figure 9.3 (a) Topical application of local analgesia ointment on a cotton bud at the injection spot. (b) Infiltration analgesia followed by (c) a transpapillary injection started from the buccal and (d) continuing to the palatal mucosa. Note blanching of the palatal papilla and mucosa in (c).

Topical application of 5% lidocaine solution for mouth washing before taking an impression can be of help for children with pronounced gag reflexes.

Local analgesic solutions

There are a number of local analgesics available for injection, both with and without vasoconstrictors, and with variable duration. The efficiency of the drug is increased and prolonged by the addition of vasoconstrictors, while the toxicity is decreased. Most commonly used in pediatric dental care are lidocaine (20 mg/mL) with adrenaline (12.5 μg/mL) and articaine (40 mg/mL) with adrenaline (5 μg/mL). Both have an intermediate analgesic duration on the pulp of approximately 60 minutes. More rarely, there may be indications for a local analgesic with long duration, e.g., for long surgical procedures, which can be obtained by bupivacaine with adrenaline.

Methods of administration

Infiltration

Infiltration is the application of a local analgesic solution around the nerve ends. The aim is to deposit the solution as close as possible to the apex of the tooth. The maxillary and mandibular bone plate in children is generally less dense than in adults, which permits a more rapid and complete diffusion of the analgesic solution through the bone. Infiltration can therefore be used with great success in the primary as well as the permanent dentition. Buccal infiltration of 0.5–1 mL solutions is sufficient for pulpal analgesia of most teeth in the maxilla of a child. There can be some difficulties anesthetizing the maxillary first permanent molars by the infiltration technique due to the zygomatic process which is closer to the alveolar bone in children than adults. Infiltration close to the apices of the maxillary central incisors should be performed carefully, as it can be very painful. In the mandible, buccal infiltration of 0.5–1 mL will often be sufficient for pain control in the primary dentition, although the effect on the second primary molar will not always be sufficient.

Technique

After penetrating a stretched and topically anesthetized mucosa the needle is directed towards the apex of the tooth (Figure 9.3b). The injection is done very slowly supraperiostally. Deposition under the periost can be very painful and should be avoided; at least before the periost itself has been anesthetized. Applying finger pressure to the area of injection prior to the injection may distract the patient’s attention. Thin (30 G) or standard (27 G) needles are recommended, and the solution should be at room temperature – never used directly from the refrigerator.

In principle, infiltration can be done anywhere in the oral cavity including the palate. However, in order to prevent painful injection in the palate, transpapillary injection is preferred (Figure 9.3c,d). All injections must be done very slowly [7].

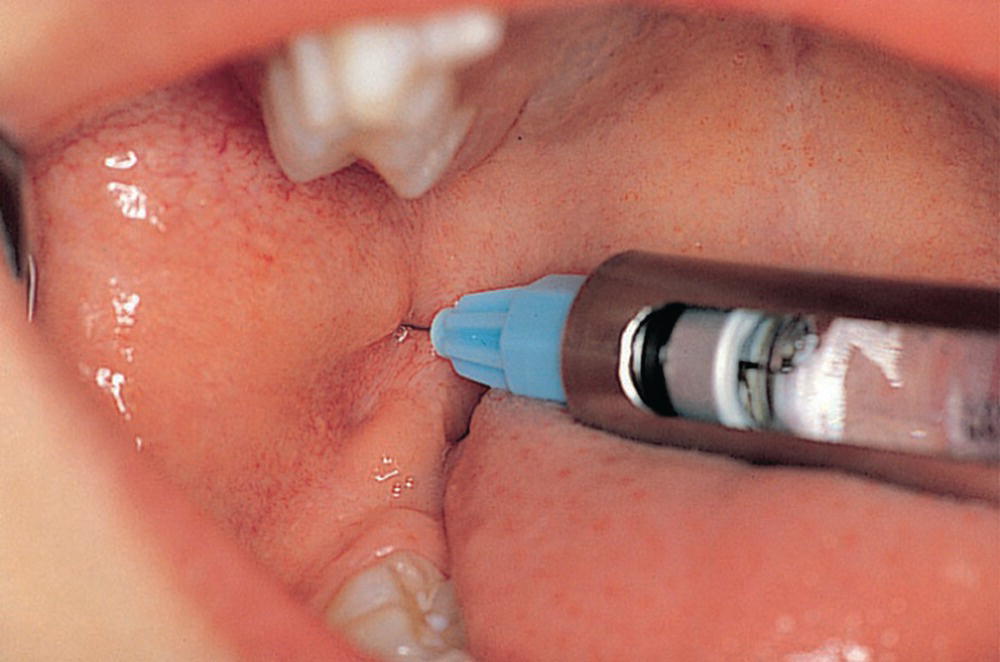

Blocks

By far the most used block analgesia in children is the mandibular foramen block (Figure 9.4). Prior to the injection, it is of great importance to prepare the child for the procedure in a way that is adjusted to its age and maturity (see Chapter 6). The patient should open maximally and the needle be introduced just laterally to the pterygomandibular fold at its deepest point (the pterygoid notch). In children, the direct injection from the opposite primary molar region is recommended. This technique requires less needle movement after tissue penetration. To secure a good block, the needle should be introduced into the tissue without any resistance. If resistance is felt, the needle is slightly withdrawn and redirected. The most common reason for resistance is the strong medial tendon from the temporal muscle along the temporal crest.

Figure 9.4 Mandibular block analgesia in a preschool child.

The foramen of the mandibular nerve lies below the occlusal plane on a line where the ramus is narrowest, two‐thirds of the way back from the anterior concavity (Figure 9.5). Palpation of the mandibular ramus will give the point of insertion, the direction in the horizontal and vertical planes, and the depth.

Figure 9.5 The position of the mandibular foramen changes during growth. However, the mandibular foramen is below the occlusive plane in children. The foramen is always situated on the line, where the ramus is narrowest, two‐thirds of the way back from the anterior concavity.

The needle is inserted between the pterygomandibular raphe and the ascending border of the mandibular bone. Inject a small amount of solution before advancing the needle into the deeper tissues. In young children, bone will be reached after about 15 mm and a 25‐mm needle can be used. However, in older children a depth of penetration up to 25 mm may be necessary, thus requiring a 35‐mm needle. When contact with the bone is obtained the needle is slightly withdrawn to avoid periost. Aspiration is performed and 1.2–1.5 mL of the solution is deposited. The lingual nerve is blocked when withdrawing the needle halfway and depositing a little of the remaining solution here. A chair‐side dental assistant is necessary when delivering a mandibular block to prevent sudden movements of hands and head in a comfortable way.

A mental block may be the result of an infiltration close to the primary mandibular first molar (Figure 9.6). Use of the regional maxillary block technique is seldom if ever required in a young child.

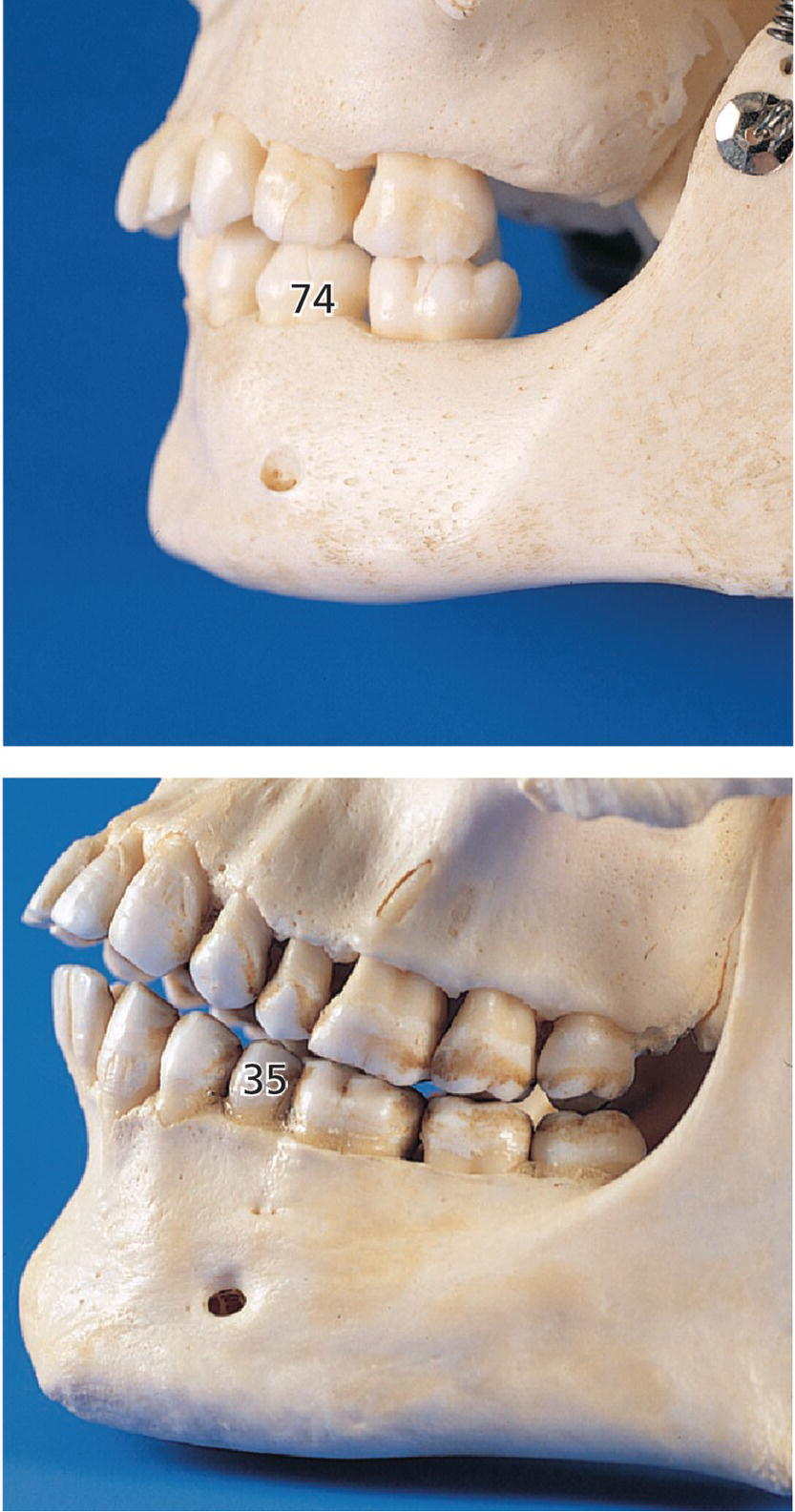

Figure 9.6 Pictures of skulls. The mental foramen is located closer to the primary mandibular first molar in children and the permanent second premolar in adults.

Computerized delivery systems

In recent years, computerized delivery systems have become part of the equipment for many dental practitioners treating children (Figure 9.7a,b). These systems deliver the analgesic solution at a constant and very slow speed which minimizes the pressure to the tissue and thereby the pain from the injection [8]. They can be used for all types of injection, both infiltration and blocks [9], but the great advantage is to be found in the palatal block procedures and in the modified periodontal ligament (PDL) injection. When using these techniques, the child does not experience the soft tissue analgesia which often is difficult to accept, especially for young children. A disadvantage is that the analgesic solution may leak into the child’s mouth and produce a bitter taste. Therefore, it is important that the chair‐side assistant is aware of the problem and uses a cotton bud to assemble the solution.

Figure 9.7 (a) The STA™ System and (b) Calaject™ are examples of computerized systems that delivers the analgesic solution with a constant and very slow speed which minimizes the pressure to the tissue and thereby the pain from the injection. (c) The AMSA injection technique.

The lightweight handpiece held like a pen enables the dentist to manipulate the needle placement with finger‐tip accuracy, rotating the needle when penetrating the mucosa, and to deliver the local analgesic with a foot‐activated contact. The flow rate is computer‐controlled and remains constant irrespective of variations in tissue resistance.

By using the computerized delivery systems, two palatal block procedures, plus a modified PDL injection, are possible:

- Anterior middle superior alveolar (AMSA) injection technique. The AMSA provides pulpal analgesia to the upper primary molars and canines, the surrounding palatal tissue and mucoperiosteum without any numbness of the lip, cheek, and muscles. For some children, this gives greater comfort and makes it easier to accept. A 30‐gauge extra‐short needle is oriented midway between the upper primary molars and midway between the free gingival margin and the palatine suture (Figure 9.7c). The suggested dosage should be delivered at a slow flow rate.

- Palatal anterior superior alveolar (P‐ASA) injection technique. This is a modified injection technique for the anterior maxilla and provides bilateral analgesia of the maxillary incisors and partially of the canines with a single‐needle penetration without involving lip and face. A 30‐gauge extra‐short needle is inserted adjacent to the incisive papilla. Topical ointment is applied in advance and it is critical to use only a slow flow rate. Aspiration is required when reaching bone contact in the canal and before delivering the anesthetic.

- PDL injection technique. This is a good alternative to the mandibular block when treating lower primary and first permanent molars. The technique is not recommended for teeth with active periodontal inflammation. The modified PDL technique employs two injection sites (mesial and distal). A 27‐ or 30‐gauge extra‐short needle is oriented with the bevel toward the tooth. The bevel should follow the surface of the tooth. The needle is advanced until resistance while the slow flow rate is activated. Approximately 0.2–0.5 mL is deposited at each side of the tooth.

General techniques

The administration of a pain‐free or an almost pain‐free injection depends primarily on the operator and factors that can be controlled by the operator: equipment, materials, and techniques (see Box 9.5).

VIDEdental - Online dental courses