9

Neurology and special senses

9A Neurology

Head injury

Head injuries can occur alone or accompany other trauma, e.g. to the maxillofacial region. This possibility always needs to be considered whenever such a patient presents. Knocks and bumps on the head are common, particularly in children, and fortunately most are minor in nature. Severe head injury accounts for about 50% of trauma-related death and between 15 and 20% of all causes of death in the 5- to 36-year-old age group.

Head injuries range from contusions, to abrasions and lacerations of the scalp; the latter can bleed profusely due to the vascularity of the tissues. It takes considerable force to fracture the skull. Fractures can involve the bones of either the base or vault. The fractures can be depressed or planar, simple or compound, the latter giving a potential portal for infection.

Significant brain injury can occur with or without damage to the overlying skull. When the skull is fractured there will almost inevitably be an associated brain injury, although it may be less than expected, the force having been dissipated in fracturing the bone.

Signs of skull fracture

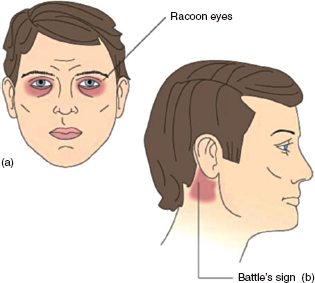

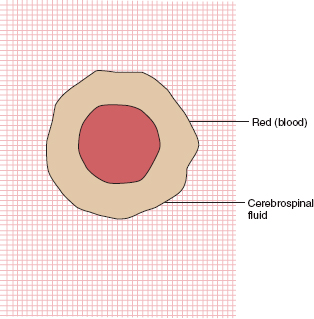

A fractured skull can occasionally occur following trauma, with little in the way of specific signs apart from overlying soft tissue swelling. Certainly a history of significant head trauma, unconsciousness with the presence of a marked swelling or deep scalp laceration should give rise to a suspicion of an underlying bony injury. Periorbital bruising (racoon eyes) and periauricular bruising (Battle’s sign) (Fig. 9A.1) are both highly suggestive of fractures to the base of skull. The presence of blood behind the eardrum or bleeding from the ear, which may show the presence of CSF (halo sign) (Fig. 9A.2) are again indicative of underlying basal injury. In all such cases computed tomography (CT) is indicated, with plain skull views mostly being limited to the absence of available CT.

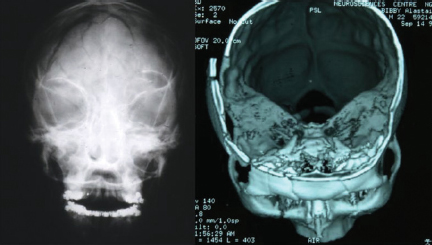

Skull fractures can be difficult to see, particularly on plain films where they can be confused with suture lines or vessel markings. With plain films, it is essential to obtain different projections to facilitate assessment. Figure 9A.3 demonstrates the advantages of CT with its ability to reveal any associated intracranial soft tissue damage.

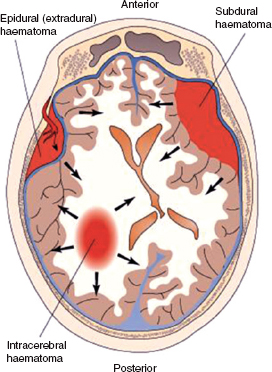

The damage sustained by the brain may be focal at the site of the injury or more diffuse. Primary damage to the brain at the site of the blow is known as the coup injury, but can also affect the brain at the opposite side as it rebounds off the skull, the contra-coup injury (Fig. 9A.4). Secondary damage to the brain can arise due to cerebral oedema, ischaemia or infection, which can compound the original injury. The normal autoregulation of cerebral blood flow tends to be lost in a head injury, making the injured brain more susceptible to hypo- or hypervolaemic change and hypoxia.

In general, head injuries are classified according to severity based on the Glasgow Coma Scale (see Table 9A.1). In the UK 80% are mild (GCS 13–15); 10% moderate (GCS 9–12), with the remainder severe in nature (GCS 3–8). The aim of management of all head injuries is to limit the amount of brain damage.

Figure 9A.1 (a) Periorbital ecchymosis, termed racoon eyes. (b) Periauricular ecchymosis, termed Battle’s sign. Copyright © 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM to accompany T. Smith and R.I. Mcleod’s Essentials of Nursing: Care of Adults and Children. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 9A.2 Halo sign. Clear drainage separating from bloody drainage is suggestive of CSF. Copyright © 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM to accompany T. Smith and R.I. Mcleod’s Essentials of Nursing: Care of Adults and Children. Reproduced with permission.

Figure 9A.3 Antero-posterior view of the skull and three-dimensionally reconstructed CT, both showing extensive skull and facial fractures.

Types of brain injury

Concussion

Concussion is one of the most common brain injuries and occurs when the trauma is minor and symptoms slight and short lived. The victim may be dizzy or lose consciousness briefly, but there is no permanent neurological damage. The person can be left feeling nauseated, have headaches, memory problems and feel tired for some time afterwards. Care needs to be taken for possible delayed intracranial bleeds.

Contusion

Contusion describes the condition where there is a bruise (bleeding) on the brain. Functions controlled by the damaged area will be lost or compromised. The individual may remain conscious, but severe contusions of the brainstem usually cause a coma, which can last from hours to a life-time.

Figure 9A.4 Coup and contre-coup injuries occur at the point of contact and when the brain rebounds from the opposite direction. Copyright © 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM to accompany T. Smith and R.I. Mcleod’s Essentials of Nursing: Care of Adults and Children. Reproduced with permission.

Diffuse axonal injury

Diffuse axonal injury arises from trauma that results in tearing of nerve structures. The result is loss of consciousness, coma and possible death. Those who survive can suffer a variety of functional impairment.

Cerebral oedema

Cerebral oedema can occur following injury. Inflammation can increase the permeability of the blood vessels in the brain space and allow fluid accumulation. For this reason, anti-inflammatory drugs and intravenous mannitol are sometimes administered in moderate to severe head injury patients in an attempt to prevent cerebral oedema, which would aggravate an already existing brain injury.

Intracranial haemorrhage

Intracranial haemorrhage may result from any head trauma. Blood leaking from ruptured vessels can enter the extradural and/or subdural spaces. Accumulation of blood within the skull increases intracranial pressure and compresses the brain tissues. If the pressure forces the brainstem inferiorly through the foramen magnum, control of blood pressure, heart rate and respiration may be lost, with resultant death. Individuals who are initially lucid and begin to deteriorate neurologically are usually bleeding intracranially and require urgent investigation, usually with CT.

Fig. 9A.5 Location of epidural, subdural and intracerebral haematomas. Copyright © 2005 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM to accompany Porth’s Pathophysiology: Concepts of Altered Health States, 7th edn. Reproduced with permission.

Extradural (epidural) haemorrhage

Extradural haemorrhage (Figs 9A.5 and 9A.6) describes a bleed into the space between the skull and dura mater often from the middle meningeal artery, and can be divided into acute and subacute forms, with symptoms of the former showing within 24–72 hours. Classically, affected individuals transiently lose consciousness at the time of injury, recover and then, after a lucid interval, deteriorate quickly, becoming deeply comatose. They develop increased blood pressure, falling pulse rate, contralateral limb weakness and ipsilateral pupillary dilatation. The subacute variation usually presents with symptoms appearing within 2–10 days after the injury. This has a somewhat better prognosis and symptoms include headache, decreasing level of consciousness and failure to show improvement.

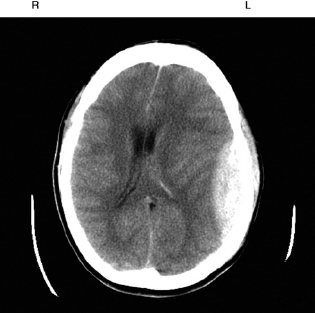

Figure 9A.6 CT image of a typical left-sided extradural haematoma showing as a lens-shaped opacity due to the tethering of the dura mater. Note the shift of the midline to the right as a result of increased intracranial pressure.

Subdural haemorrhage

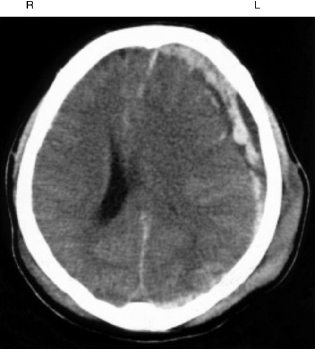

Subdural haemorrhage (Fig. 9A.7) is most probably a complication of a high velocity injury, and the patient is usually unconscious from the time of injury. Essentially, the bleeding occurs below the dura mater and spreads over the brain surface. This condition is associated with a deteriorating level of consciousness and the underlying brain damage is more severe. As a result, the prognosis tends to be worse than for extradural haematoma.

In both extradural and subdural haemorrhage cases, the aim of surgical management is to decrease the intracerebral pressure by removing the haematoma (through burr holes or craniotomy) and repair or seal off the damaged vessels.

Intracerebral haemorrhage

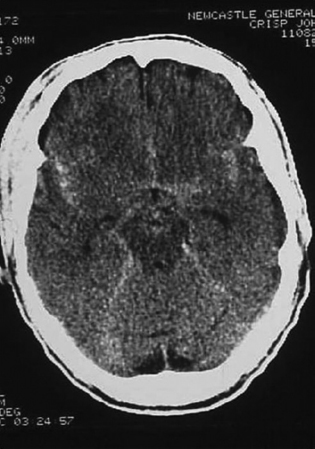

Intracerebral haemorrhage (Fig. 9A.8) arises as a result of bleeding from small arteries or veins into the subcortical white matter and is more common following the rupture of a vascular anomaly such as an aneurysm. Symptoms include lucid intervals followed by loss of consciousness. Focal signs tend to depend on the location of the bleed and can include headache, hemiplegia, ipsilateral pupil dilation and progressive intracranial pressure with potential for herniation through the foramen magnum. In these cases, management involves identifying the source of bleeding and, if possible, sealing it off. This may be achieved by a neurosurgical approach, clipping of the vessel or via a radiologically guided procedure inserting a coil into the aneurysm sac causing the adjacent blood to coagulate and seal the vessel off.

Figure 9A.7 CT showing swelling on the left side of the head with an underlying subdural haematoma with the blood more diffusely spread around the left side of the brain. Note pressure effects of midline shift to the right and collapse of the left ventricle.

Assessment

With any history of head injury, however minor, it is essential that the patient is fully assessed. This should include:

- Glasgow Coma Scale (see below)

- Vital signs

- History of loss of consciousness

- Pupil reflexes

- Motor responses.

Even if normal, these should be documented as a baseline from which to monitor as there can often be a subtle or sudden change. It is essential to look for clinical indications of expanding lesions such as:

- Localised/focal signs

- Visual field defects

- Eye deviations

- Cerebral or cranial nerve signs.

Figure 9A.8 CT of an intracerebral bleed showing diffuse spread of blood around the brain possibly as a result of a leaking cerebral aneurysm.

In addition, there may be general signs of increased intracranial pressure such as:

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Restlessness

- Irritability.

As these signs can occasionally come on gradually within hours or even days of the incident, it is essential that friends or relatives closest to the patient are aware of the development of such signs and be advised to return the patient to the Accident and Emergency department of their nearest hospital as soon as possible.

Table 9A.1 Glasgow Coma Scale for head injury

| Eye opening | |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To loud voice | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Verbal response | |

| Orientated | 5 |

| Confused/disorientated | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Best motor response | |

| Obeys | 6 |

| Localises | 5 |

| Withdraws (flexion) | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion posturing | 3 |

| Extension posturing | 2 |

| None | 1 |

General signs and symptoms of brain injury

Direct injury, increasing intracranial pressure, and compression or displacement of brain tissue can all cause altered levels of awareness as well as general signs and symptoms including:

- Altered level of consciousness

- Altered level of orientation

- Alterations in personality

- Amnesia

- retrograde (unaware of events after accident)

- anterograde (cannot remember before incident)

- Cushing’s reflex – increased blood pressure, slowing pulse rate

- Vomiting (often without nausea)

- Body temperature changes

- Changes in reactivity of pupils

- Body posturing.

Where there is altered mental status or the patient is unresponsive, the condition can be monitored using the GCS (Table 9A.1).

The GCS is scored between 3 and 15; 3 being the worst and 15 the best. It is composed of three parameters: best eye response, best verbal response and best motor response.

Spinal injury

Spinal damage can accompany any other body injury but especially following a high velocity impact such as in a fall or road traffic accident. It can range in severity from ligamentous damage such as in the whiplash injury to the neck through a variety of fractures of the vertebrae. The danger of such injuries is the effect on the underlying spinal cord. This can vary from complete sectioning to partial damage, with the resultant neurological deficit being dependent on the site of the injury.

Like all neurological tissue, the spinal cord has relatively poor regenerative properties. Consequently, prevention and minimising damage are key to the prognosis. This includes careful handling of any victim where such an injury is suspected; thorough assessment including radiological examination using plain film views or CT and transfer to a unit specialising in the management of spinal injuries as soon as possible.

Complications

The modern management of head injuries is ideally undertaken in specialist neurosurgical units with the ability to provide the necessary intensive care with continued ventilation, management of intracranial pressure, cerebral perfusion, oxygenation and, where indicated, surgery.

Essentially these complications fall into three categories – physical, cognitive and emotional – and to some degree depend on the site and extent of the damage.

- Physical effects include loss of motor function, coordination, paralysis, extreme tiredness, epilepsy and speech problems.

- Cognitive effects include memory loss (either for before or after the accident), reduced attention span and slower reaction times.

- Emotional effects can vary from depression, to anxiety, irrational behaviour and emotional lability with a tendency to laugh or cry more readily than before. In some instances, the patient can develop a complete change of personality.

These effects can be extremely devastating not only for the patient but also for their families and friends. Some effects may ameliorate with time but some will be permanent as a result of the relatively poor ability of nervous tissue to repair. Affected individuals may require a long period of convalescence in specialist units where they can receive appropriate physiotherapy, psychological support and occupational therapy to help with adaptation to disability and, where possible, learn to maintain their independence.

Brain abscess

Brain abscesses may be secondary to oral sepsis or infection elsewhere in the middle ear or paranasal sinuses. A patient with congenital heart disease is at increased risk. Such abscesses can be a complication of infective endocarditis and this should be specifically asked about in the history of a patient suffering from a brain abscess. Brain abscess can occasionally arise from a dental source. The signs and symptoms vary depending on the location of the abscess. CT and MRI scans are useful in localisation and diagnosis. Urgent surgical drainage is required.

Space-occupying lesions

A space-occupying lesion in the context of the brain implies the presence of a tumour but could also be used to encompass pathology such as a haematoma or abscess. Such lesions may affect any age and may lead to partial seizures, possibly developing to generalised epilepsy. Imaging is essential to determine the size and position of any suspected space-occupying lesion.

Meningitis

Meningitis is an infection of the meninges (membranes) that envelop the brain and spinal cord. The source of infection may be viral, bacterial or fungal. Fungal infections are rare and are usually seen in immunocompromised patients. It is important to remember that bacterial meningitis can occur secondary to maxillofacial injuries involving the middle third of the face. Prompt treatment with antimicrobials (prophylactically in trauma cases) should be undertaken. The viral type of meningitis is usually mild and self-limiting. The patient with meningitis has a severe headache, feels nauseated or vomits, and is often drowsy. The painful, stiff neck and aversion to light are well known symptoms. Meningitis caused by the bacterium Neisseria meningitidis may produce a purpuric rash on the skin and can progress to adrenocortical failure as a result of bleeding into the adrenal cortex.

Herpetic encephalitis is rare. When it occurs it is essential that prompt treatment with aciclovir is instituted. A variety of infections and tumours can be seen in HIV-associated neurological disease. The neurological effects of such lesions vary depending on the main site affected.

9B ENT

Deafness

Deafness may be of two main types – conductive or sensorineural.

Conductive deafness

This is usually due to wax in the external auditory meatus, but otitis media or otosclerosis can also cause it.

Figure 9B.1 A patient with Paget’s disease. The head becomes progressively enlarged.

Sensorineural deafness

Potential causes of sensorineural deafness are listed below:

- Ménière’s disease

- Acute labyrinthitis

- Head injury

- Paget’s disease (Fig. 9B.1)

- Excess noise

- Overdose of certain drugs, e.g. gentamicin.

Clinical testing

A simple test of hearing can be carried out by blocking one ear and, from behind the patient, saying a number increasingly loudly until the patient hears. Other tests can differentiate conductive from sensorinural deafness.

Rinne’s test

A vibrating tuning fork should be placed on the mastoid process. When the patient can no longer hear it the fork should be moved to a position 4 cm from the external auditory meatus. If the sound is no longer heard, bone conduction is better than air conduction (normally the converse applies). This suggests conductive deafness or a false positive due to sensorineural deafness, ‘hearing’ the sound in the contralateral ear.

Weber’s test

A vibrating tuning fork is placed in the middle of the forehead and the patient is asked whether the sound is located to one side or the other, or centrally. In unilateral sensorineural deafness the sound will be heard on the ‘good side’. In conductive deafness the sound is localised to the ‘bad’ side.

Tinnitus

Tinnitus is a sound of ringing or whistling in the ears. This can occur as a result of impacted wax or Ménière’s disease. Sometimes a cause is never found.

Clearly, any underlying cause should be removed if it can be identified.

Vertigo

Vertigo is the illusion of movement. In the majority of cases it indicates disease of the labyrinth or its neurological connections. Ménière’s disease comprises a syndrome of vertigo, deafness and tinnitus. Attacks are variable in length from minutes to hours and can include vomiting and nystagmus. The latter is a term that is used to describe oscillation of the eyes on attempted fixation. It can be a physiological phenomenon and must be maintained for a few beats to be pathological.

The treatment of Ménière’s diseases is symptomatic with prochlorperazine and sometimes betahistine.

Dizziness

This is a very common presenting symptom to general medical practitioners. It is a less specific phenomenon than vertigo.

Infections and inflammatory disorders of the ear, nose, sinuses and tonsils

Ear infections

Furunculosis is the term used to denote infection of hair follicles. This is usually staphylococcal in origin. Diabetes should be considered as an underlying predisposing factor in these patients. Treatment is with heat and topical applications. If there is systemic involvement, antibiotics such as amoxicillin and flucloxacillin may be required.

Otitis externa (infection of the external ear) often occurs after excessive scratching due to an itchy skin condition such as eczema. All infected material must be removed and topical preparations used for treatment. In otitis media (infection of the middle ear), pain in the ear may be followed by purulent discharge. The ear drum will perforate. Antibiotics are required for treatment. Continuing discharge may indicate mastoiditis (more commonly seen prior to the introduction of antibiotics). Treatment is intravenous antibiotics and myringotomy (an incision through the ear drum). In resistant cases, mastoidectomy may be required. In ‘glue ear’, there is an accumulation of serous or viscous material. The main predisposing factor to this is when the eustachian tube, which normally opens during swallowing, is blocked, e.g. by the adenoids. Glue ear is the most common cause of hearing loss in children. If fluid persists for longer than 6 months and there is diminished hearing, myringotomy may be required with aspiration of fluid and insertion of grommets. Removal of the adenoids is also effective.

Nasal obstruction

The most common cause of nasal obstruction is the sequel to an URTI. It is common for children to insert foreign bodies in the nose. In children, large adenoids or choanal atresia and post-nasal space tumours should be considered. In adults, a deviated nasal septum, either as the result of trauma or developmental in origin, can cause obstruction to the nasal passages. Polyps and chronic sinusitis are also commonly found problems. Allergic rhinitis may be seasonal or perennial – there is a significant correlation with the pollen count and symptoms include sneezing, pruritis and rhinorrhoea. Antihistamines are the mainstay of treatment. From the maxillofacial point of view, it is important in middle third of face fractures that CSF rhinorrhoea is actively excluded or confirmed. Fractures through the roof of the ethmoid labyrinth may result in leak of CSF.

In cases of nasal trauma, it is important that the anterior part of the nose is examined to exclude a septal haematoma. These can cause nasal obstruction and should be immediately evacuated as there is a risk of cartilage necrosis and nasal collapse if this is not done.

Nose bleed (epistaxis) is a common problem. Most nose bleeds come from blood vessels on the nasal septum. In older people, bleeding is more commonly arterial in origin from a part of the nose known as Little’s area. Many nose bleeds are idiopathic in origin but can be associated with degenerative arterial disease and hypertension. It should always be remembered that a nose bleed, particularly in more elderly patients, may be due to a tumour in the nose or the paranasal sinuses. Patients who are anticoagulated are at increased risk of epistaxis. In terms of management, it is important that the overall physiological picture of the patient is remembered. Estimation of the vital signs should be carried out to exclude shock, and consideration should be given to the site of the bleeding and to stop it appropriately. In order to reduce venous pressure, most patients with epistaxis are nursed in the sitting position. If the patient is clinically shocked, they must be placed supine. Firm and uninterrupted pressure of the nostrils between finger and thumb for at least 10 min is carried out. If this does not stop the bleeding, the clot is removed from the nose and any identified bleeding points cauterised. If it is not possible to identify a distinct bleeding point, the nose is packed with a ribbon gauze pack, which has been soaked in BIPP (Bismuth Iodoform Paraffin Paste). In some trauma cases, an anterior pack will not be sufficient and a posterior nasal pack needs to be placed. This can be achieved by inflating a Foley catheter after it has been passed through the nostril with the balloon lying in the post-nasal space. Once the balloon is inflated, the catheter can be pulled anteriorly to apply pressure to the bleeding area. Both nostrils will usually need to be catheterised.

Paranasal sinuses

Acute sinusitis

A secondary bacterial infection of the sinuses may occur following a viral infection. Around 1 in 10 maxillary sinusitis infections are secondary to initial viral infection. In acute sinusitis there may be a yellow/green nasal discharge, pain and tenderness to palpation over the affected area and a raised temperature. Treatment includes analgesia, nasal inhalations and a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Swimming should be discouraged since it promotes the spread of pus within the sinuses.

Chronic sinusitis

Chronic sinusitis may present as post-nasal drip of mucus and a bad taste in the mouth. The nose will be blocked and there will be pain over the bridge of the nose or in the malar region. It is important to try and correct any underlying cause. Some form of drainage procedure should be instituted to prevent further problems.

Tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is a common throat condition. The appearance of a rash after 48 hours on the neck or the chest raises suspicion of scarlet fever in childhood sore throat. A rash is not seen periorally and therefore the rash is described as having circumoral pallor. The tongue has a white coating, leaving prominent papillae – the ‘strawberry’ tongue. The cause is a group A Streptococcus. On examination, the tonsils are clearly inflamed and may have an exudate of pus. Children will often complain of abdominal pain that co-exists with the tonsillitis. Older children and adults tend to complain of sore throat, fever and malaise. They may have dysphagia and palpable painful swollen cervical lymph glands.

There is controversy regarding the use of antibiotics for the treatment of tonsillitis as in about half of the cases the cause will be viral. If antibiotics are used, penicillin is the antibiotic of choice. Amoxicillin should not be used as it will cause a rash in patients whose infection is due to Epstein–Barr virus (EBV). Several years ago tonsillectomy was a commonly performed procedure in those who had recurrent tonsillitis. The number of tonsillectomies in recent years has significantly declined. Recurrent tonsillitis is, however, still an indication for tonsillectomy. In acute situations, surgical drainage is required. A peritonsillar infection, known as a quinsy, still necessitates the operation of tonsillectomy. On rare occasions tonsils can be so large as to cause cor pulmonale or obstructive sleep apnoea. If a case of tonsillitis is unchecked or untreated, a retropharyngeal abscess will develop.

Carcinoma of the pharyngeal tonsil

Cancers of the pharyngeal tonsil are most common in the elderly patient. They will complain of dysphagia, odynophagia (painful swallowing) and otalgia. A particular warning sign is the case of unilateral tonsillitis. Carcinomas are usually squamous cell in origin. The precise form of treatment will depend on the histopathological nature of the tumour.

Stridor

The term stridor describes noises which are produced by inspiration when the larynx or trachea has become narrowed. It may be accompanied by dysphagia. It is particularly seen in children due to the small size of their airway, but can also be seen in adults. In most adults, however, laryngeal problems tend to produce hoarseness. Due to its effects on the airway, stridor is a situation that should be treated as an emergency.

9C Neurological disorders and dental practice

There are a number of neurological conditions that may be encountered in dental practice. It is important that a dental practitioner has a broad knowledge of the main neurological conditions since they may affect the provision of dental treatment.

Relevant points in the history

The patient may give a history of ‘blackouts’. It is important to be precise about what a patient means by this term as this can indicate anything from a loss of consciousness to dizziness. When a history of blackouts is given, information obtained from a witness might be useful. The more that is known about the nature of such an event, the better it can be anticipated and effectively managed (or prevented). There are several cardiovascular disorders that can lead to a ‘blackout’. These are also considered here.

Table 9C.1 Main points in the history in the dental patient with possible neurological disorders

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The main points in the history are summarised in Table 9C.1.

Syncope may be vaso-vagal in origin (the simple faint) or may occur in response to certain situations such as coughing. A vaso-vagal attack may be precipitated by the fear of dental treatment, heat or a lack of food. It occurs due to a reflex bradycardia and peripheral vasodilation. Onset is not instantaneous and the patient will look pale, often feel sick and notice a ‘closing in’ of visual fields. It cannot occur when a patient is lying down, and placing the patient flat with legs raised is the treatment. Jerking of limbs may occur. In carotid sinus syncope, hypersensitivity of the carotid sinus may cause syncope to occur on turning the head. Unlike vaso-vagal syncope this may happen in the supine position.

Patients may suffer from epilepsy. If this presents as a blackout the most likely type is grand mal. A description of the fit is useful as this may enable early recognition. Precipitating factors should be asked about, as should questioning about altered breathing, cyanosis or tongue biting during a fit. The latter is virtually a diagnostic feature of this type of epilepsy. Medication taken and its efficacy should be assessed in terms of the degree of control achieved. Tonic–clonic or grand mal epilepsy is classically preceded by a warning or aura, which may comprise an auditory, olfactory or visual hallucination. A loss of consciousness follows, leading to convulsions and subsequent recovery. The patient may be incontinent during a fit. The ‘tonic phase’ gives way to a ‘clonic phase’ in which there is repetitive jerky movements, increased salivation and marked bruxism. After a fit of this type, a patient may sleep for up to 12 hours. If the fit continues for more than 5 min or continues without a proper end-point, ‘status epilepticus’ is said to be present. This is an emergency situation that requires urgent intervention with a benzodiazepine, e.g. intravenous diazepam or buccal midazolam (see Chapter 20).

Table 9C.2 Possible causes of loss of consciousness or ‘blackout’

| Vaso-vagal syncope | Simple faint |

| ‘Situational’ syncope | Cough |

| Micturition | |

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Transient ischaemic attack | |

| Orthostatic hypotension | On standing from lying |

| Signifies inadequate vasomotor reflexes, e.g. elderly patients on tablets to lower blood pressure | |

| ‘Drop attacks’ | Sudden weakness of legs usually resolved spontaneously |

| Stokes–Adams attacks | Transient arrhythmia |

| Anxiety |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses