Hepatology

Key Points

• Alcoholic liver disease is increasing, as are deaths from liver disease

• Viral hepatitis is common, increasing and transmissible in health-care facilities

• Health-care professionals must be immunized against hepatitis B virus

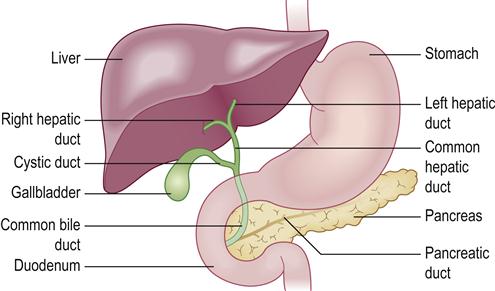

Life is impossible without the liver. The liver (hepar) consists of hepatocytes, organized for optimal contact with sinusoids (blood vessels) and bile ducts. It makes and breaks down sugar, proteins and fats; stores nutrients; produces bile; and removes metabolic products and other toxins from the blood. Bile drains to the gallbladder and, via the bile duct, to the small intestine, at which point it is intimately associated with the head of the pancreas, swelling of which may cause biliary obstruction and jaundice (Fig. 9.1).

The liver, through the function of the Kupffer cells (mononuclear phagocytes) that line the sinusoids forms part of the lymphoreticular system (along with macrophages in the lymphoid tissue and spleen) and plays an important role by capturing and digesting bacteria, fungi, parasites, effete blood cells, and cellular debris. The liver turns glucose into glycogen (stored in the liver). This is converted back into glucose when required, maintaining stable blood glucose levels. Excess carbohydrates and protein are converted to fat. The liver also makes proteins – blood proteins (e.g. most blood-clotting factors using vitamin K metabolites), and albumin, hormones, transporter proteins and complement. The liver underlies normal haemostasis, since it produces blood clotting factors I, II, VII, IX, X and XI; bile salts which aid vitamin K absorption (needed for clotting factors); and the hormone thrombopoietin which stimulates the bone marrow megakaryocyte production of platelets. The liver also forms bile essential for fat digestion and absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E and K), and produces or stores these vitamins and vitamin B12; it also stores minerals (e.g. copper and iron). Bile (gall) is made up of water, cholesterol, phospholipids, bicarbonate, bile pigments and bile salts; it is a bitter yellow or green fluid secreted by hepatocytes, stored in the gallbladder between meals, and discharged into the duodenum upon eating, being required for fat and fat-soluble vitamin absorption. The bile salts sodium glycocholate and sodium taurocholate are produced by the liver from cholesterol; they help emulsify fats for their absorption and facilitate the activity of pancreatic lipase.

The breakdown of haemoglobin, cholesterol, proteins, sex steroids and many drugs occurs, at least partly, in the liver. The enzyme haem oxygenase acts on haem to form biliverdin, which in turn is converted into bilirubin. Biliverdin and bilirubin are termed bile pigments. Bilirubin is not water-soluble (unconjugated bilirubin) and needs a carrier (albumin) to be transported. In the liver, bilirubin is conjugated by combining with glucuronic acid and becomes water-soluble conjugated bilirubin. This then enters the bile, and flows into the bile duct and finally the intestine, where it can be excreted in, and colours, the stool after being changed into urobilinoids. Alternatively, the process of conjugation can be reversed by beta-glucuronidase, which converts the conjugated bilirubin back into unconjugated bilirubin. Unlike conjugated bilirubin, unconjugated bilirubin can be reabsorbed from the intestine back into the blood (enterohepatic recirculation). Conjugated bilirubin can also be excreted in the urine, which it darkens. Increased levels of bilirubin in the blood can cause the body, especially the sclerae of the eyes, to appear yellow (jaundice).

Water-soluble toxins and waste products can be eliminated via the kidneys in the urine, but non–water-soluble toxins need to be chemically modified by the liver to allow this process to occur. Digested proteins in the form of amino acids are broken down further in the liver, a process known as deamination. Nitrogenous products such as ornithine and arginine are converted to urea, which is excreted into the urine by the kidneys. Sex steroids, such as the masculinizing hormone testosterone and the feminizing hormone oestrogen, are inactivated in the liver.

Most drugs, including alcohol, are metabolized/excreted via the liver (Table 9.1). In particular, oral drugs are absorbed by the gut and transported via the portal circulation to the liver. In the liver, these drugs may undergo first-pass metabolism, in which they are modified, activated or inactivated before they enter the systemic circulation.

Table 9.1

Some drugs metabolized by the liver

| Local anaesthetics | Bupivacaine, lidocaine, mepivacaine, prilocaine, articaine |

| Analgesics | Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin, codeine, ibuprofen, meperidine |

| Antimicrobials | Ampicillin, azole antifungals, clindamycin, metronidazole, tetracyclines, vancomycin |

| Sedatives | Diazepam |

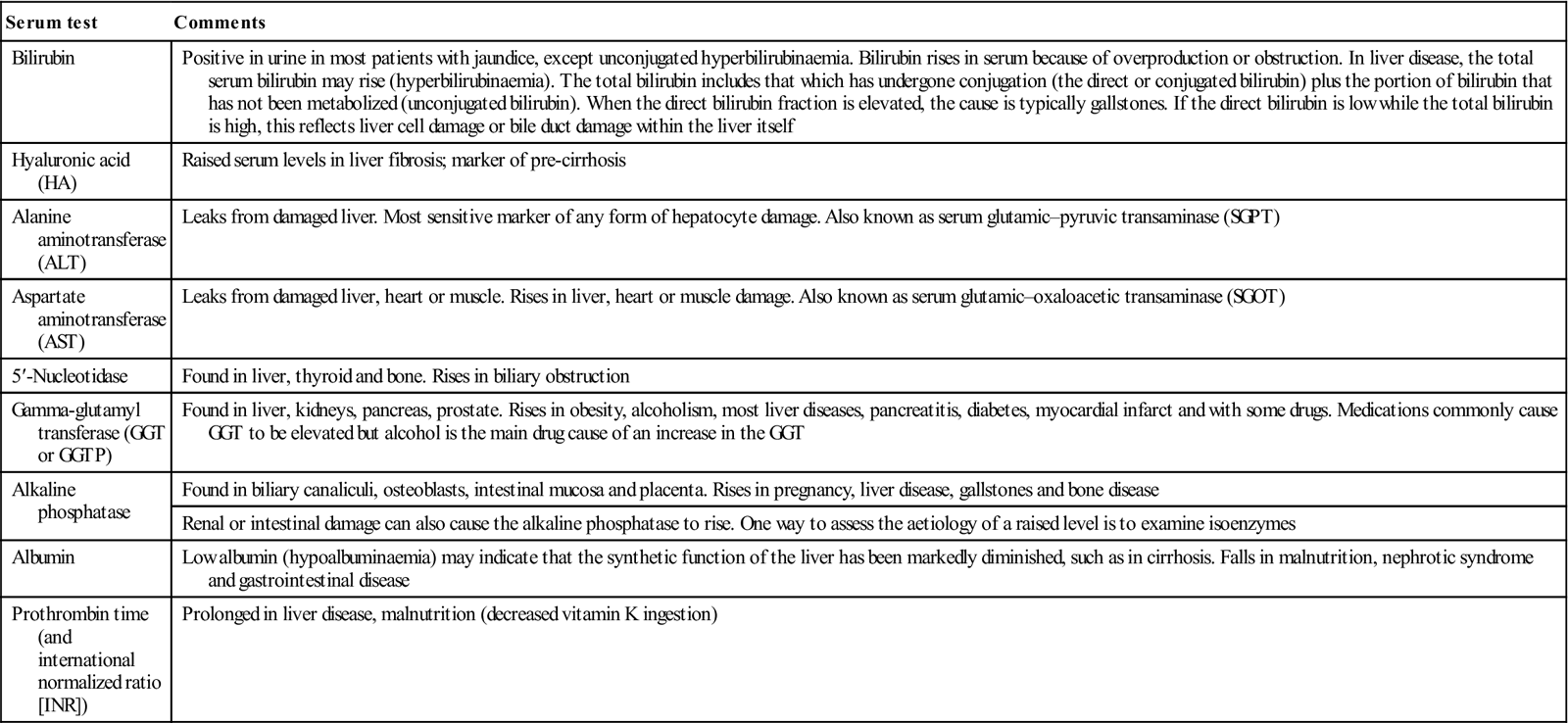

The diagnosis of liver disease depends on the history, physical examination and evaluation of liver function tests (Table 9.2). Apart from bilirubin, liver enzyme levels may also be increased in the blood in various disorders. Aminotransferase levels are sensitive indicators of liver-cell injury (Table 9.3).

Table 9.2

< ?comst?>

| Serum test | Comments |

| Bilirubin | Positive in urine in most patients with jaundice, except unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia. Bilirubin rises in serum because of overproduction or obstruction. In liver disease, the total serum bilirubin may rise (hyperbilirubinaemia). The total bilirubin includes that which has undergone conjugation (the direct or conjugated bilirubin) plus the portion of bilirubin that has not been metabolized (unconjugated bilirubin). When the direct bilirubin fraction is elevated, the cause is typically gallstones. If the direct bilirubin is low while the total bilirubin is high, this reflects liver cell damage or bile duct damage within the liver itself |

| Hyaluronic acid (HA) | Raised serum levels in liver fibrosis; marker of pre-cirrhosis |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | Leaks from damaged liver. Most sensitive marker of any form of hepatocyte damage. Also known as serum glutamic–pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | Leaks from damaged liver, heart or muscle. Rises in liver, heart or muscle damage. Also known as serum glutamic–oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) |

| 5′-Nucleotidase | Found in liver, thyroid and bone. Rises in biliary obstruction |

| Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT or GGTP) | Found in liver, kidneys, pancreas, prostate. Rises in obesity, alcoholism, most liver diseases, pancreatitis, diabetes, myocardial infarct and with some drugs. Medications commonly cause GGT to be elevated but alcohol is the main drug cause of an increase in the GGT |

| Alkaline phosphatase | Found in biliary canaliculi, osteoblasts, intestinal mucosa and placenta. Rises in pregnancy, liver disease, gallstones and bone disease |

| Renal or intestinal damage can also cause the alkaline phosphatase to rise. One way to assess the aetiology of a raised level is to examine isoenzymes | |

| Albumin | Low albumin (hypoalbuminaemia) may indicate that the synthetic function of the liver has been markedly diminished, such as in cirrhosis. Falls in malnutrition, nephrotic syndrome and gastrointestinal disease |

| Prothrombin time (and international normalized ratio [INR]) | Prolonged in liver disease, malnutrition (decreased vitamin K ingestion) |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

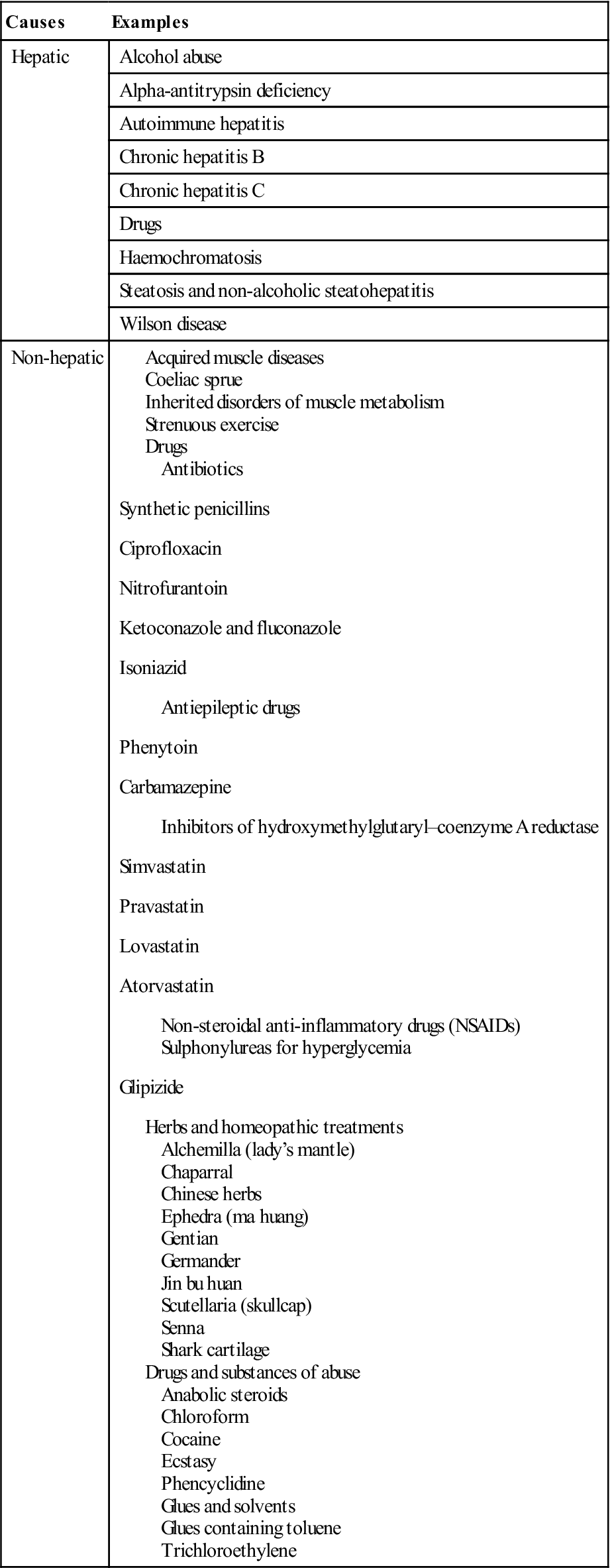

Table 9.3

Causes of raised aminotransferase levels

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Alkaline phosphatase levels may be raised if there is biliary obstruction, but also vary with age. Rapidly growing adolescents can have serum alkaline phosphatase levels that are twice those of healthy adults as a result of the leakage of bone alkaline phosphatase into blood. Also, serum alkaline phosphatase levels normally increase gradually between the ages of 40 and 65 years, particularly in women.

Raised levels of gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) have been reported in a wide variety of clinical conditions, including pancreatic disease, myocardial infarction, renal failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes and alcoholism. High serum GGT levels are also found in patients who are taking medications such as phenytoin and barbiturates.

Congenital Liver Disease

General and clinical aspects

Transient neonatal jaundice is common, usually due to the normal breakdown of haemoglobin around birth, and is of little consequence. Severe neonatal jaundice can be caused by prematurity, or haemolysis such as in rhesus incompatibility, biliary atresia or hepatic disease; it can lead to kernicterus (damage to the brain basal ganglia), which can be fatal, or cause epilepsy or choreoathetosis (with or without learning impairment) and deafness. Rare familial liver enzyme disorders that can cause jaundice are shown in Appendix 9.1.

Dental aspects

Disorders associated with an early rise in serum levels of conjugated bilirubin (mainly biliary atresia and haemolysis, such as in rhesus disease) can cause a greenish discolouration of the teeth and dental hypoplasia.

Acquired Liver Disease

Liver disease is increasing, due especially to alcohol use, obesity and infections; in the decade to 2009 in the UK, liver-associated deaths increased by one-fifth. A bleeding tendency, dangers from certain drugs, liability to infections and sometimes infectious hazards are factors to consider in the dental patient with liver disease.

Hepatitis

The liver has some powers of regeneration but this capacity can be exceeded by repeated or extensive damage by infective agents, alcohol, drugs or poisons. The word ‘hepatitis’ means inflammation of the liver and also often refers to a group of viral infections that affect the liver, but hepatitis can also be caused by drugs or autoimmune disorders. The most common types of viral infection are hepatitis A, hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Alcohol abuse is the major drug causing acute hepatitis.

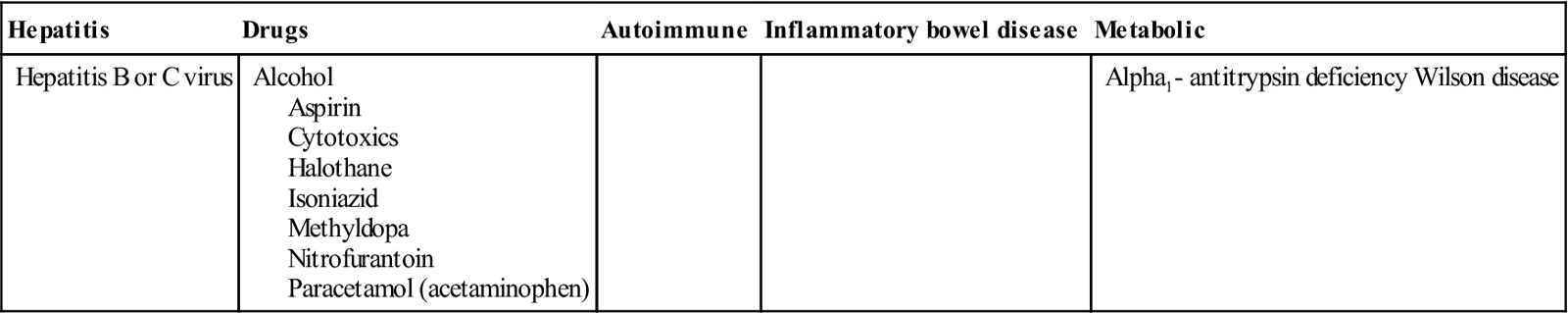

Chronic hepatitis is the term for hepatitis that persists longer than 6 months; it may follow acute hepatitis (or appear without warning) and may progress to cirrhosis. The most important causes of chronic hepatitis are hepatitis C virus, alcohol, drugs and autoimmune hepatitis (Table 9.4). Chronic liver disease includes chronic hepatitis, and cirrhosis. Excessive alcohol intake, viral hepatitis and drugs also account for the majority of cases of cirrhosis (Box 9.1). Liver diseases can have many effects, according to the degree of liver damage – including jaundice, a bleeding tendency, and impaired drug and metabolite degradative and excretory activities (Table 9.5). Many patients with liver disease are asymptomatic and the problem frequently remains subclinical for years or decades. Malaise, anorexia and fatigue are common, sometimes with low-grade fever and upper abdominal discomfort.

Table 9.4

< ?comst?>

| Hepatitis | Drugs | Autoimmune | Inflammatory bowel disease | Metabolic |

| Hepatitis B or C virus | Alcohol Aspirin Cytotoxics Halothane Isoniazid Methyldopa Nitrofurantoin Paracetamol (acetaminophen) |

Alpha1– antitrypsin deficiency Wilson disease |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

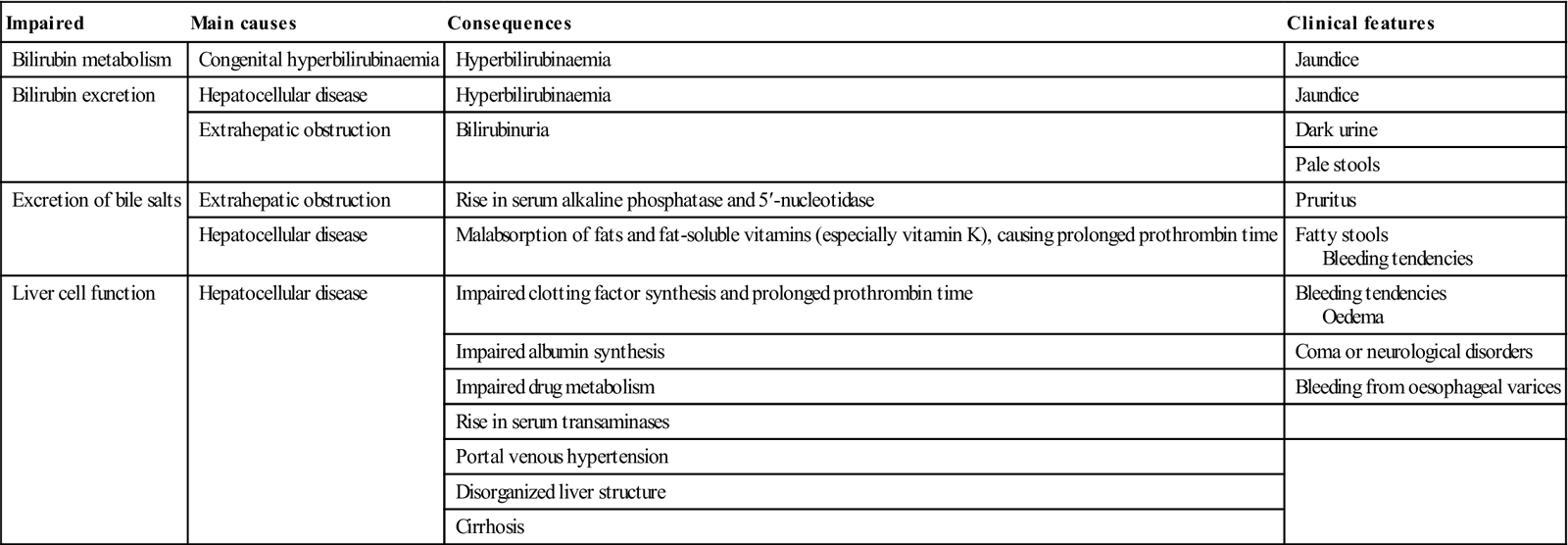

Table 9.5

Manifestations of liver diseases

< ?comst?>

| Impaired | Main causes | Consequences | Clinical features |

| Bilirubin metabolism | Congenital hyperbilirubinaemia | Hyperbilirubinaemia | Jaundice |

| Bilirubin excretion | Hepatocellular disease | Hyperbilirubinaemia | Jaundice |

| Extrahepatic obstruction | Bilirubinuria | Dark urine | |

| Pale stools | |||

| Excretion of bile salts | Extrahepatic obstruction | Rise in serum alkaline phosphatase and 5′-nucleotidase | Pruritus |

| Hepatocellular disease | Malabsorption of fats and fat-soluble vitamins (especially vitamin K), causing prolonged prothrombin time | Fatty stools Bleeding tendencies |

|

| Liver cell function | Hepatocellular disease | Impaired clotting factor synthesis and prolonged prothrombin time | Bleeding tendencies Oedema |

| Impaired albumin synthesis | Coma or neurological disorders | ||

| Impaired drug metabolism | Bleeding from oesophageal varices | ||

| Rise in serum transaminases | |||

| Portal venous hypertension | |||

| Disorganized liver structure | |||

| Cirrhosis |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Bilirubin ester is normally excreted in bile and is one of the factors that colour the faeces. If bilirubin is not conjugated (enzyme defect or parenchymal liver disease) or excreted (biliary obstruction), it accumulates in the body and colours the skin and mucous membranes (jaundice) and the whites of the eyes (icterus); it is detectable clinically at levels greater than 40 micromol/L, and the urine darkens.

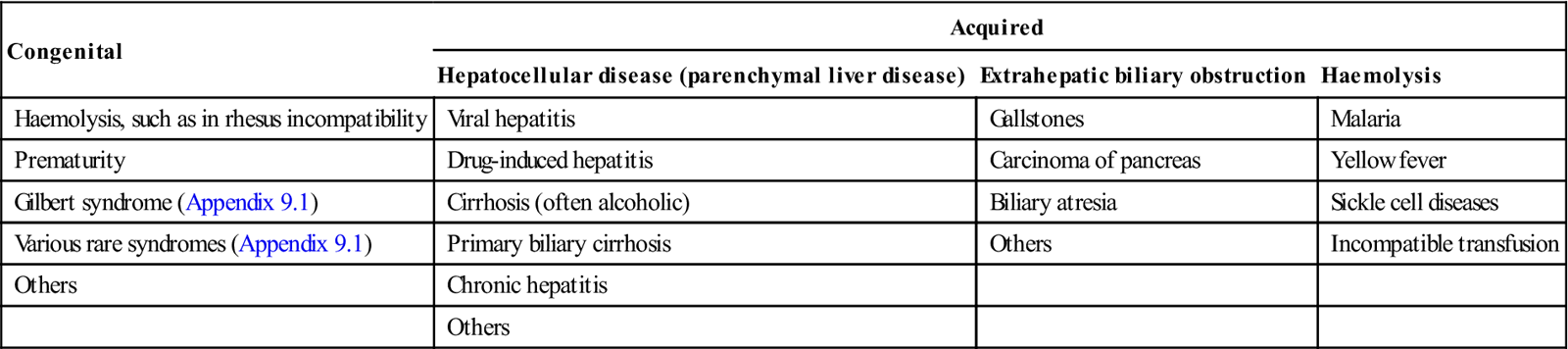

Jaundice is often caused by liver disease but may also result from haemolysis, abuse of alcohol or other drugs, or infection (Table 9.6).

Table 9.6

< ?comst?>

| Congenital | Acquired | ||

| Hepatocellular disease (parenchymal liver disease) | Extrahepatic biliary obstruction | Haemolysis | |

| Haemolysis, such as in rhesus incompatibility | Viral hepatitis | Gallstones | Malaria |

| Prematurity | Drug-induced hepatitis | Carcinoma of pancreas | Yellow fever |

| Gilbert syndrome (Appendix 9.1) | Cirrhosis (often alcoholic) | Biliary atresia | Sickle cell diseases |

| Various rare syndromes (Appendix 9.1) | Primary biliary cirrhosis | Others | Incompatible transfusion |

| Others | Chronic hepatitis | ||

| Others | |||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Pale, fatty faeces and malabsorption result from failure of bile salts to reach the intestine (obstructive diseases), causing malabsorption of fats, and of the fat-soluble vitamins (e.g. vitamin K) needed for clotting-factor synthesis. Bile salts accumulating in the blood may cause itching, nausea, anorexia and vomiting.

A bleeding tendency results from depressed synthesis of blood-clotting factors and excess fibrinolysins. Prothrombin time (PT), the international normalized ratio (INR) and activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) are all increased. Chronic bleeding may cause anaemia.

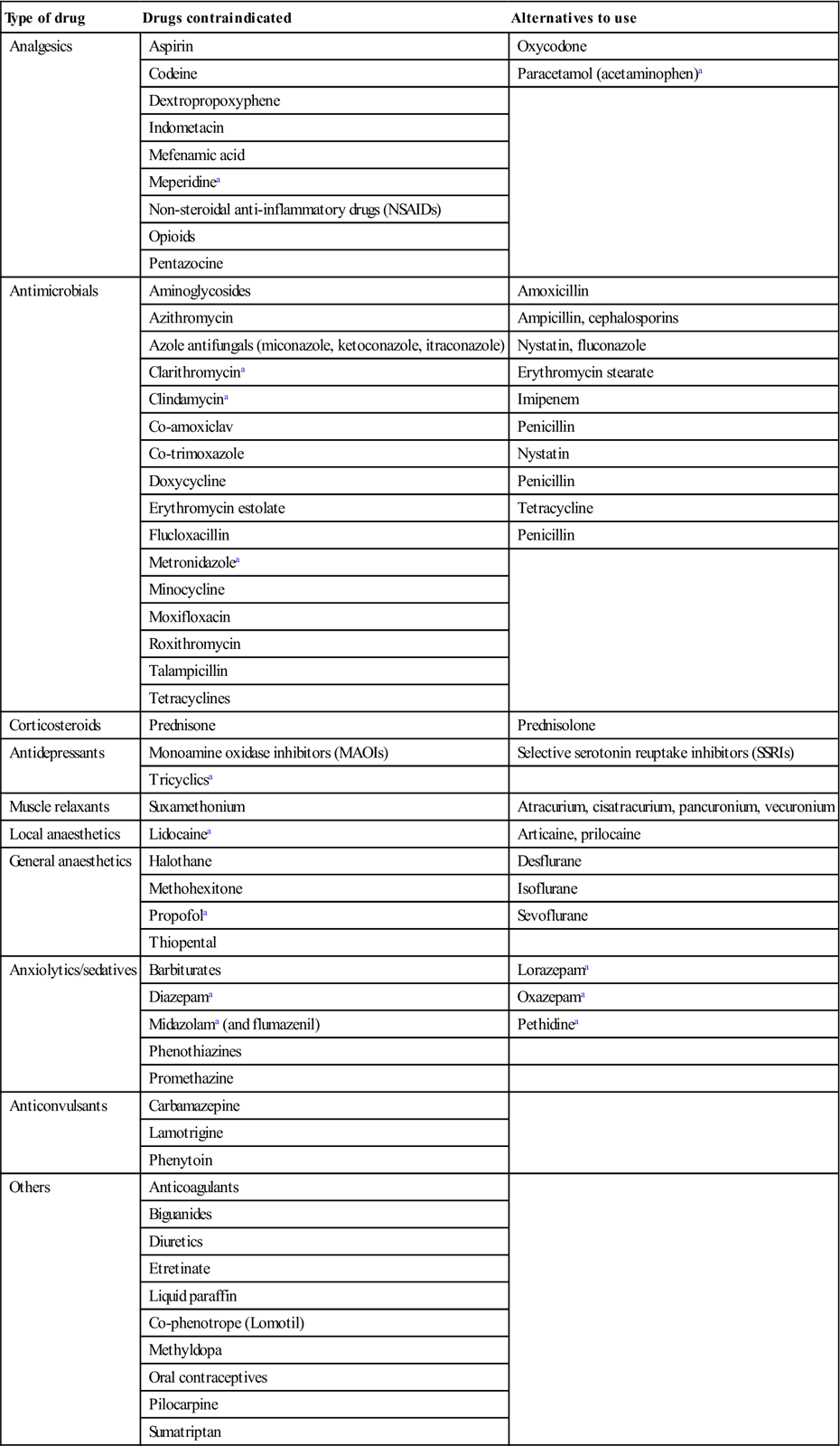

Drugs (e.g. alcohol and barbiturates) that can induce the hepatic cytochrome P450 system can lead to diminished effects of other drugs, such as the contraceptive pill, phenytoin or warfarin. By contrast, some drugs (e.g. cimetidine, omeprazole, sulphonamides and valproate) impair P450 activity, causing enhanced activity of drugs such as carbamazepine, ciclosporin, phenytoin or warfarin (Table 9.7).

Table 9.7

Drugs contraindicated and alternatives in liver disease

< ?comst?>

| Type of drug | Drugs contraindicated | Alternatives to use |

| Analgesics | Aspirin | Oxycodone |

| Codeine | Paracetamol (acetaminophen)a | |

| Dextropropoxyphene | ||

| Indometacin | ||

| Mefenamic acid | ||

| Meperidinea | ||

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | ||

| Opioids | ||

| Pentazocine | ||

| Antimicrobials | Aminoglycosides | Amoxicillin |

| Azithromycin | Ampicillin, cephalosporins | |

| Azole antifungals (miconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole) | Nystatin, fluconazole | |

| Clarithromycina | Erythromycin stearate | |

| Clindamycina | Imipenem | |

| Co-amoxiclav | Penicillin | |

| Co-trimoxazole | Nystatin | |

| Doxycycline | Penicillin | |

| Erythromycin estolate | Tetracycline | |

| Flucloxacillin | Penicillin | |

| Metronidazolea | ||

| Minocycline | ||

| Moxifloxacin | ||

| Roxithromycin | ||

| Talampicillin | ||

| Tetracyclines | ||

| Corticosteroids | Prednisone | Prednisolone |

| Antidepressants | Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) |

| Tricyclicsa | ||

| Muscle relaxants | Suxamethonium | Atracurium, cisatracurium, pancuronium, vecuronium |

| Local anaesthetics | Lidocainea | Articaine, prilocaine |

| General anaesthetics | Halothane | Desflurane |

| Methohexitone | Isoflurane | |

| Propofola | Sevoflurane | |

| Thiopental | ||

| Anxiolytics/sedatives | Barbiturates | Lorazepama |

| Diazepama | Oxazepama | |

| Midazolama (and flumazenil) | Pethidinea | |

| Phenothiazines | ||

| Promethazine | ||

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine | |

| Lamotrigine | ||

| Phenytoin | ||

| Others | Anticoagulants | |

| Biguanides | ||

| Diuretics | ||

| Etretinate | ||

| Liquid paraffin | ||

| Co-phenotrope (Lomotil) | ||

| Methyldopa | ||

| Oral contraceptives | ||

| Pilocarpine | ||

| Sumatriptan |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

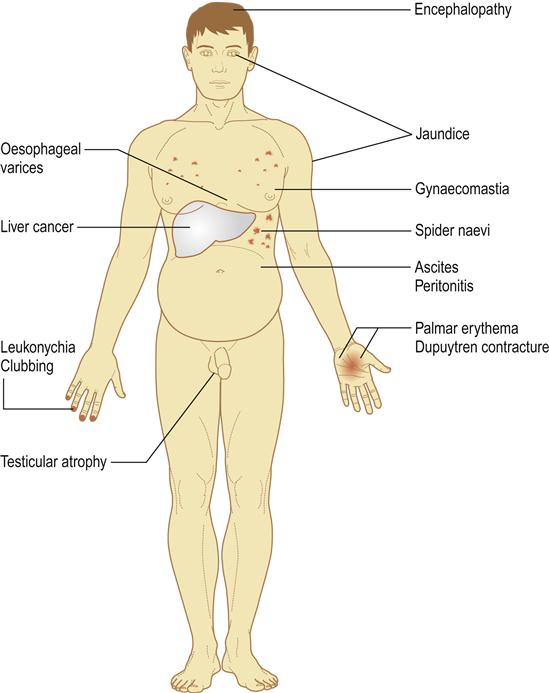

Cirrhosis chiefly affects the middle-aged or elderly, and is frequently asymptomatic in its earlier stages. Anorexia, malaise and weight loss are common, and effects can be widespread (Box 9.2; Fig. 9.2).

Viral Hepatitis

Many viruses cause hepatitis (Table 9.8). The term ‘viral hepatitis’ used in health care usually refers to infection by hepatitis B, D or C viruses (HBV, HDV, HCV), which are transmitted parenterally (Table 9.9). Jaundice during childhood is often caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV) and typically is of little consequence; hepatitis B and C are the most relevant to health care, since the delivery of health care has the potential to transmit viral hepatitis to both health-care professionals (HCPs) and patients. Outbreaks have occurred in outpatient settings, haemodialysis units, long-term care facilities, and hospitals, primarily as a result of unsafe injection practices; reuse of needles, fingerstick devices and syringes; and other lapses in infection control.

Table 9.8

| Hepatitis viruses | Herpesviruses | Others |

| Hepatitis A virus | Cytomegalovirus | Coxsackie B virus |

| Hepatitis B virus | Epstein–Barr virus | Yellow fever |

| Hepatitis C virus | Herpes simplex virus | |

| Hepatitis D virus | ||

| Hepatitis E virus | ||

| Hepatitis G virus | ||

| SEN viruses | ||

| Transfusion-transmitted virus (torque teno virus; TTV) |

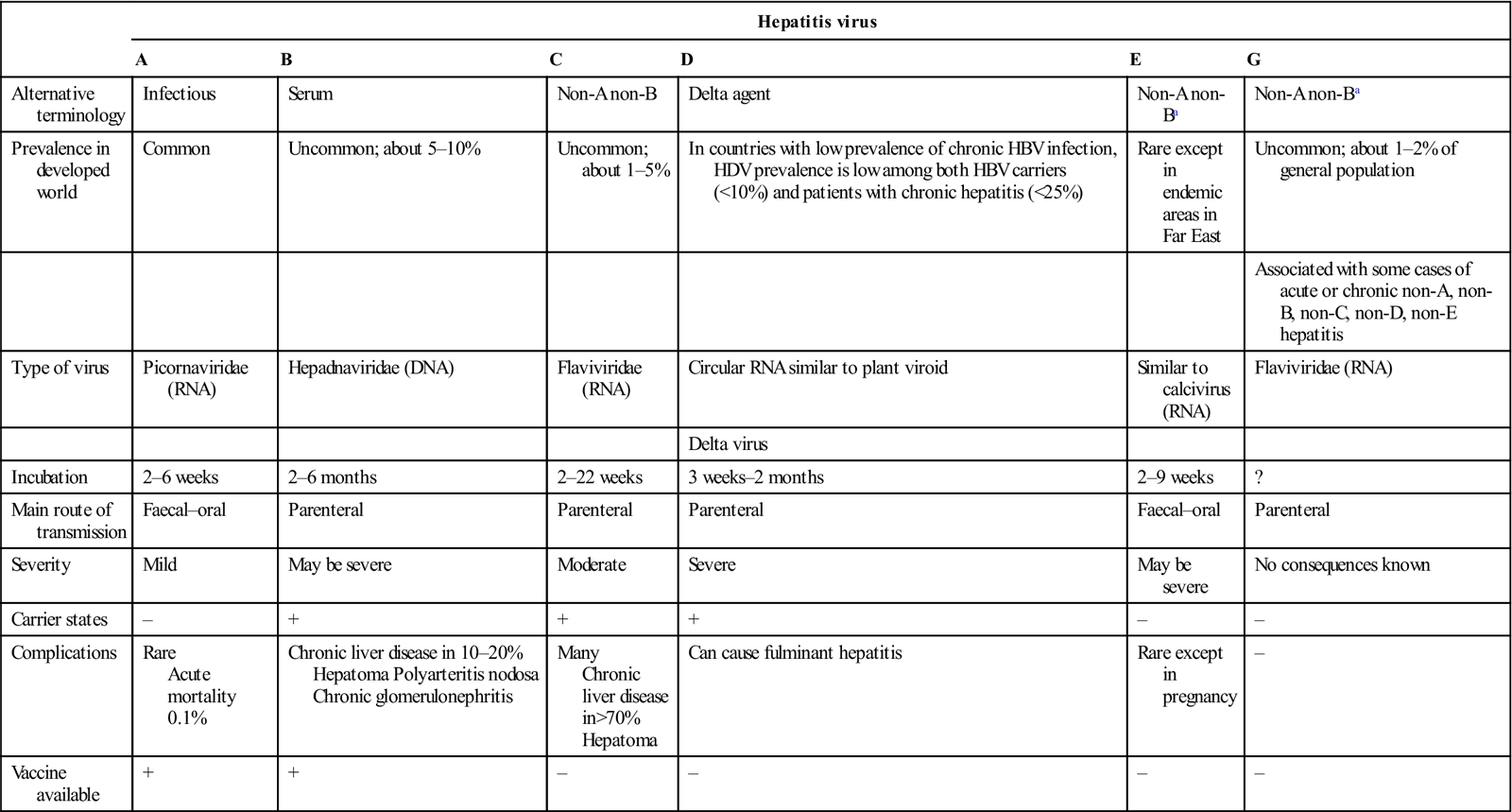

Table 9.9

Comparative features of more common forms of viral hepatitis

< ?comst?>

| Hepatitis virus | ||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | G | |

| Alternative terminology | Infectious | Serum | Non-A non-B | Delta agent | Non-A non-Ba | Non-A non-Ba |

| Prevalence in developed world | Common | Uncommon; about 5–10% | Uncommon; about 1–5% | In countries with low prevalence of chronic HBV infection, HDV prevalence is low among both HBV carriers (<10%) and patients with chronic hepatitis (<25%) | Rare except in endemic areas in Far East | Uncommon; about 1–2% of general population |

| Associated with some cases of acute or chronic non-A, non-B, non-C, non-D, non-E hepatitis | ||||||

| Type of virus | Picornaviridae (RNA) | Hepadnaviridae (DNA) | Flaviviridae (RNA) | Circular RNA similar to plant viroid | Similar to calcivirus (RNA) | Flaviviridae (RNA) |

| Delta virus | ||||||

| Incubation | 2–6 weeks | 2–6 months | 2–22 weeks | 3 weeks–2 months | 2–9 weeks | ? |

| Main route of transmission | Faecal–oral | Parenteral | Parenteral | Parenteral | Faecal–oral | Parenteral |

| Severity | Mild | May be severe | Moderate | Severe | May be severe | No consequences known |

| Carrier states | – | + | + | + | – | – |

| Complications | Rare Acute mortality 0.1% |

Chronic liver disease in 10–20% Hepatoma Polyarteritis nodosa Chronic glomerulonephritis | Many Chronic liver disease in>70% Hepatoma |

Can cause fulminant hepatitis | Rare except in pregnancy | – |

| Vaccine available | + | + | – | – | – | – |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Jaundice in the teenager or young adult may be due to viral hepatitis A, B, C, D or E. Several of these viruses, particularly HAV and hepatitis E virus (HEV), are transmitted faeco–orally. Some, especially HAV and HBV, and probably HCV, can be spread sexually. Hepatitis A and E are more of a problem in resource-poor areas and are transmitted faeco–orally; hepatitis E is more severe among pregnant women, especially in the third trimester.

Hepatitis B has long been of greatest importance but, in the absence of a vaccine, hepatitis C has become a more serious problem. Standard (universal) precautions against transmission of infection must always be employed, since these viruses, particularly HBV, HCV and HDV can be transmitted in blood and blood products and in other body fluids; they may be passed on by practices in which infection control is lacking, particularly in intravenous drug use where there is needle- or syringe-sharing. Any practice in which there is a skin breach, such as body-piercing or tattooing (Fig. 9.3), can also constitute a risk. Co-infection with other blood-borne agents, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), is common, particularly in intravenous drug users.

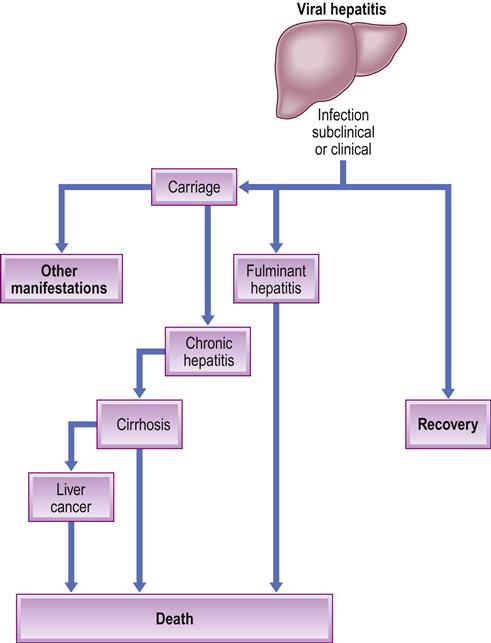

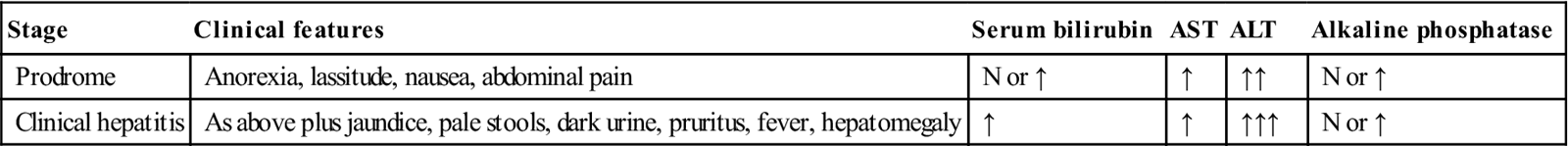

All hepatitis viruses can cause acute, or short-term, illness, and jaundice is common (Fig. 9.4). Some hepatitis viruses, particularly HCV and HBV, also have a small acute mortality. HBV, HCV and HDV can also cause chronic hepatitis, in which the infection is prolonged – sometimes lifelong – and may be associated with virus carriage, chronic liver disease and liver cancer (hepatoma; hepatocellular cancer); they can also be responsible for aplastic anaemia and other extrahepatic manifestations. The clinical and laboratory features of viral hepatitis are summarized in Table 9.10.

Table 9.10

Acute viral hepatitis: clinical and biochemical features

< ?comst?>

| Stage | Clinical features | Serum bilirubin | AST | ALT | Alkaline phosphatase |

| Prodrome | Anorexia, lassitude, nausea, abdominal pain | N or ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ | N or ↑ |

| Clinical hepatitis | As above plus jaundice, pale stools, dark urine, pruritus, fever, hepatomegaly | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑↑ | N or ↑ |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Hepatitis A (‘infectious hepatitis’)

General aspects

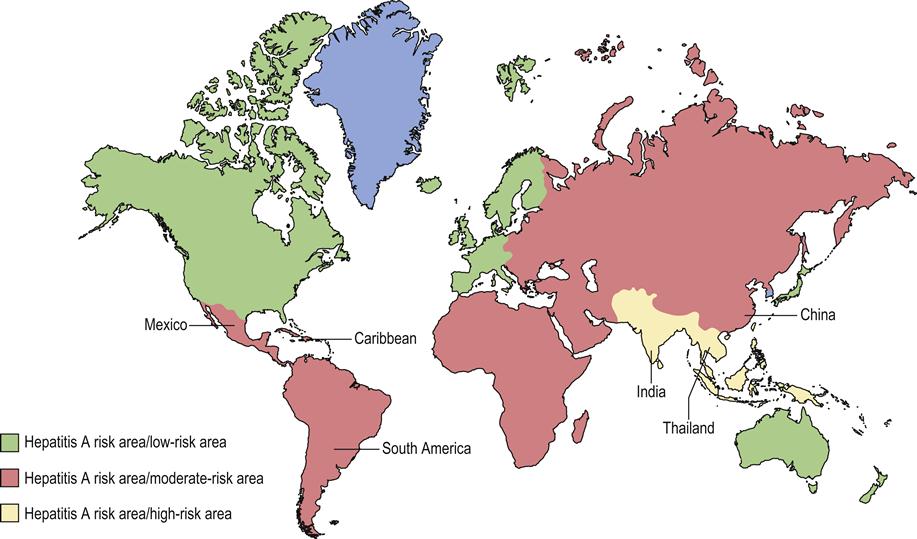

Hepatitis A is caused by HAV and is rarely serious. Hepatitis A is endemic throughout the world, seen particularly where socioeconomic and living conditions are poor and, in those areas, infection (and consequent immunity) is common in childhood (Fig. 9.5). In the developed world, many people reach adulthood without infection and have no immunity, and therefore are at risk from infection if they travel to endemic areas.

Spread of hepatitis A is largely faeco–oral, by consumption of contaminated water or food, particularly raw shellfish. For example, nearly 300 000 persons were infected in one outbreak in Shanghai, originating from contaminated clams. Hepatitis A can also be transmitted sexually and by close person-to-person contact, and in body fluids including saliva. Persons in the armed forces, food handlers, HCPs, sewage workers, travellers to areas of high endemicity, children />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses