9

Head and Neck Anatomy and Physiology

- the gross anatomy of the skull

- the head and neck musculature

- the nerve supply to the head and neck, including the dentally relevant cranial nerves

- the blood supply to the head and neck

- disorders of the dentally relevant cranial nerves

The anatomy of the head and neck region of the human body is of relevance to the dental nurse in providing the underpinning knowledge required to understand their role within the dental team, as well as knowledge of the full range of topics covered in their dental nurse training programme. Dental nurses are often asked for information and advice from patients with regard to their oral health, and within the bounds of their profession, they will be able to give more accurate and useful information when it is based on the head and neck area in full, rather than just on teeth. For instance, a full understanding of the subject of local anaesthesia requires knowledge of the skull and oral anatomy, as well as of the drugs used.

Anatomy of the skull

The skull is the topmost part of the bony skeleton of the body, the head, and is made up of three main areas.

- Cranium – the hollow cavity which surrounds the brain.

- Face – the front vertical part of the skull, containing the orbital cavities of the eyes and the nasal cavity of the nose.

- Jaws – the upper and lower jaws of the oral cavity, supporting the teeth and the tongue, and providing the openings for the respiratory tract and the digestive tract.

All the bones of the skull except the lower jaw, the mandible, are fixed to each other by immovable joints called sutures.

The base (underside) of the cranium articulates with the topmost bone of the vertebral column, the atlas, and allows nodding movements of the head.

Like most bones in the body, the skull develops in the fetus as cartilage, which is gradually converted to bone during the growth of the body into adulthood.

The outer layer of all bone is called compact bone, and is perforated by many natural bony openings (foramina) to allow the passage of nerve and blood vessels. The inner layer is called cancellous bone and is quite sponge-like in appearance, because if it was a solid structure it would make the bone too heavy for the muscles to be able to lift. Nerves and blood vessels run freely within the spongy structure of the cancellous layer, and pass into and out of it through the foramina.

Cranium

At birth and during infancy, the bony plates making up the cranium are separated from each other by two natural membrane-covered spaces called fontanelles, which allow growth of the brain without any bony restriction. During growth, the spaces gradually become filled with bone and close together to provide a protective helmet surrounding the brain. The bony plates join together like a jigsaw puzzle at the coronoid sutures. By the age of 18 months the fontanelles should have closed completely, following the natural growth together of the bony plates making up the cranium.

The cranium is composed of eight bones which are separated by the coronoid sutures – these are visible on a dry skull as the zig-zagged joints between the bony plates. The bones themselves are as follows.

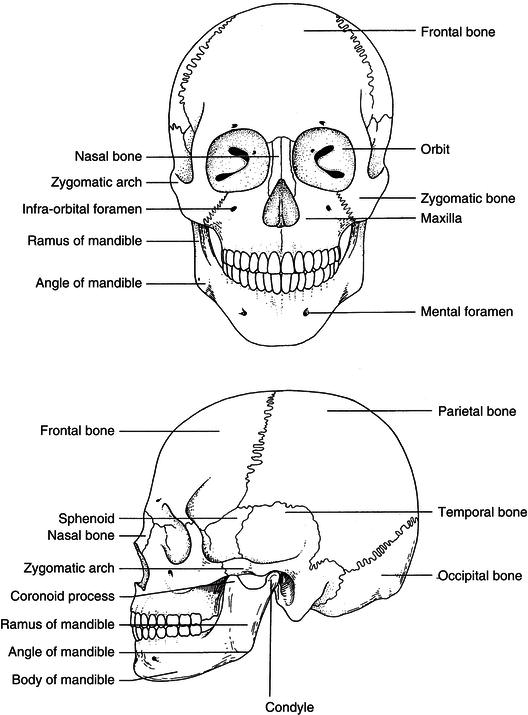

Figure 9.1 The skull.

- Frontal bone – single plate at the front of the cranium above the eyes, forming the forehead.

- Parietal bones – pair of plates forming the top and the greater area of the sides of the cranium.

- Temporal bones – pair of fan-shaped plates in the temple region of the lower sides of the cranium, in front of the ears.

- Occipital bone – single plate at the back and partial underside of the cranium.

- Sphenoid bone – single plate forming the majority of the base (underside) of the cranium.

- Ethmoid bone – single plate at the front base section of the cranium, immediately behind the nose.

The skull and cranial bones are illustrated in Figure 9.1.

All the sensory nerve cells running from the body to the brain and all the motor nerves running from the brain to the body have to pass in and out of this bony cavity, and they do so through the many natural foramina on the underside of the cranium. Similarly, all the blood vessels supplying the head and neck structures pass through these same foramina or between natural spaces between adjacent bones, called fissures.

In addition to these bony openings, some cranial bones also have various bony projections and plates on their outer surfaces, which serve as attachments for ligaments and muscles associated with head and jaw movements or which form part of various facial structures.

The largest foramen of all in the cranium is the foramen magnum, which opens through the occipital bone and allows the exit of the spinal cord from the base of the brain and into the vertebral column of the spine.

The 12 pairs of nerves that branch off directly from the underside of the brain itself, and which supply the head and neck region only, are called the cranial nerves – those relevant to the dental nurse are discussed later. The nerves that supply the rest of the body all branch off the spinal cord at various points down the vertebral column, and are referred to as the systemic nerves. They are not relevant to the dental nurse.

Face

The face is composed of 11 bones which are separated from each other by sutures, as in the cranium. The main bones themselves are as follows.

- Vomer – single bone behind the nasal cavity, that connects the cranial and facial regions of the skull together.

- Lacrimal bones – pair of fragile bony plates forming the inner wall of the orbital cavities (eye sockets).

- Nasal bones – pair of bones forming the bridge of the nose.

- Nasal turbinates – pair of fragile curled bones projecting into the nasal cavity, which increase the contact of inspired air with the nasal mucosa; this aids debris removal before inhalation to the lungs, and warms the air as it passes over the capillary beds covering the bones. They are separated in the midline by the nasal septum.

- Palatine bones – pair of bony plates forming the posterior section of the hard palate, and the side wall of the nasal cavity.

- Zygomatic bones – pair of facial bones that articulate with the cranium posteriorly and extend anteriorly into the zygomatic arch (cheek bone) to articulate with the maxilla.

The skull and facial bones are shown in Figure 9.1.

Jaws

Although strictly speaking the jaw bones are actually part of the facial skeleton, they are considered separately as they are of such importance to the dental team. The two jaws are each made up of a pair of bones which are fixed solidly in their midlines.

- Maxilla – pair of bones forming the upper jaw, the lower border of the orbital cavities, the base of the nose and the anterior portion of the hard palate.

- Mandible – appears as a single horseshoe-shaped bone forming the lower jaw, with its posterior vertical bony struts articulating with the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ).

Maxilla and palatine bones

The maxilla effectively forms the middle third of the face and as with various other cranial bones, it has several foramina and bony projections which are dentally relevant.

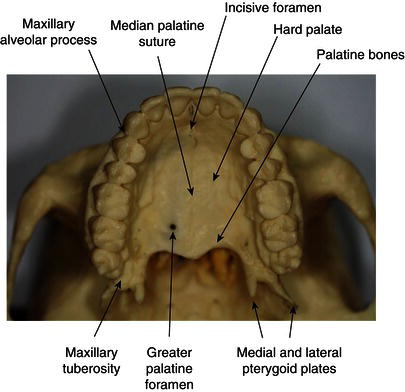

The maxilla is made up of two bones which are separated above by the nasal cavity. They join together below the nose as the front section of the hard palate. The back section of the hard palate is formed by the palatine bones, and the whole palate forms the floor of the nose and the roof of the oral cavity, or mouth (Figure 9.2).

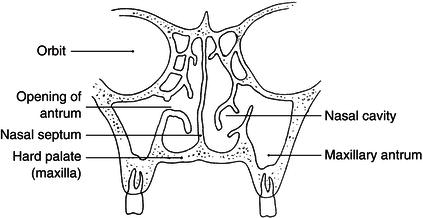

Each side of the maxilla forms part of the eye socket, the nose and the front of the cheekbone. The two maxilla bones themselves are hollow within, because if they were solid they would be too heavy to allow the head to be lifted up. Each hollow space is called the maxillary antrum or sinus, and lies just above the root apices of the upper molar and second premolar teeth (Figure 9.3). This hollow space can be easily perforated during the extraction of these teeth, causing an unwanted connection between the mouth and the antrum called an oroantral fistula. A natural connection between the nasal cavity and the antra exists, to allow drainage of the sinuses to occur, and to give resonance to the voice.

Figure 9.2 Palate – anatomical landmarks.

Figure 9.3 Facial bones and air spaces (cross-section).

Inflammation of these air spaces (sinusitis) due to a respiratory infection often mimics dental pain in these teeth, or conversely a dental infection can be mistaken for sinusitis.

The two maxilla bones join together in the centre-line of the face at the intermaxillary suture and the lowest portions of these two sections form the alveolar process. This horseshoe-shaped structure is where both sets of upper teeth develop before birth, and later erupt as the upper primary and then secondary dentition.

The back end of each side of the alveolar process is called the maxillary tuberosity, and this can be fractured off during difficult upper wisdom tooth extractions (Figure 9.4).

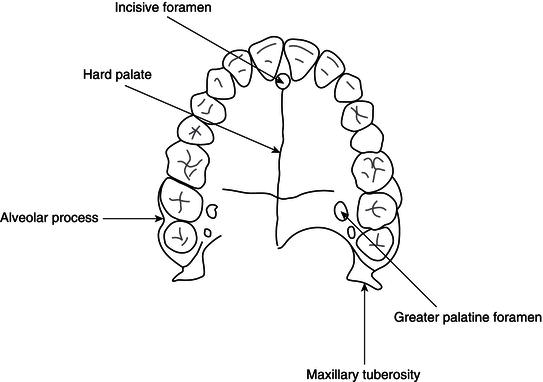

The maxilla and palatine bones (Figure 9.5) are perforated by several foramina to allow passage of the nerves and blood vessels supplying the upper teeth and their surrounding soft tissues, the four main ones being as follows.

- Infraorbital foramen – beneath the eye sockets, through which the nerves supplying the upper teeth and their labial soft tissues pass.

- Greater and lesser palatine foramina – at the back of the hard palate, through which the nerves supplying the palatal soft tissues of the upper posterior teeth pass.

- Incisive foramen – at the front centre of the hard palate, through which the nerves supplying the palatal soft tissues of the upper anterior teeth pass.

Figure 9.4 Extracted upper tooth with fractured tuberosity.

Figure 9.5 Palate and maxillary teeth.

Mandible

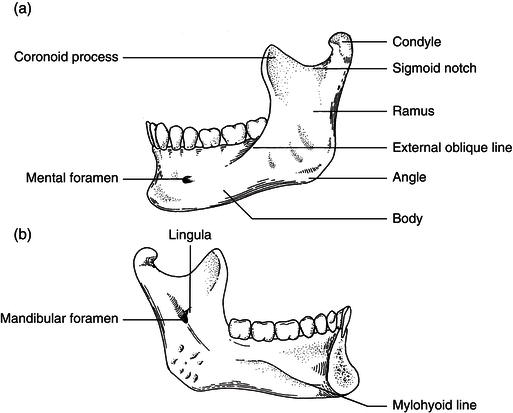

The mandible is also made up of two bones, joined together in the centre-line at the mental symphysis to create a single horseshoe-shaped structure, and with its two back ends bent up vertically to the horseshoe. The vertical section is called the ramus of the mandible, the horizontal section is called the body of the mandible, and the point at which they join is the angle of the mandible (Figure 9.6).

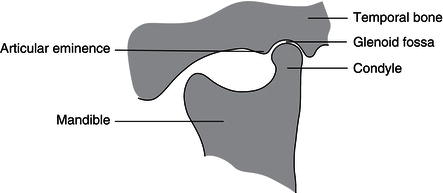

The mandible’s only connection with the rest of the skull is at the two temporomandibular joints (TMJ), where the bone moves as a hinge joint and allow the mouth to open and close. The point at which the mandible connects with the temporal bone at the TMJ is the head of condyle (Figure 9.7). The muscles of mastication, which allow jaw-closing and chewing movements, all connect between the cranium and various points on the mandible, as discussed later.

The mandible also has an alveolar process running around it, which supports all the lower teeth. Below this process, on the inner side of the body of the mandible lies a ridge of bone called the mylohyoid ridge, where the mylohyoid muscle attaches to form the floor of the mouth. A bony ridge also lies on the outer surface of the ramus of the mandible, called the external oblique ridge, which marks the base of the alveolar process in this area.

The front edge of the ramus rises up to the coronoid process, and the dip between it and the head of condyle at the back of the ramus is called the sigmoid notch. When the mouth is closed, the coronoid process slots under the zygomatic arch of the face.

The two foramina in the mandible which are of interest to the dental nurse are as follows.

- Mandibular foramen – halfway up the inner surface of the ramus and protected by the bony lingula, through which the nerve supplying the lower teeth and some of their surrounding soft tissues enters the mandible.

- Mental foramen – on the outer surface of the body of the mandible, between the positions of the premolar teeth, through which the same nerve exits the mandible.

Figure 9.6 The mandible. (a) Outer side. (b) Inner side.

Figure 9.7 Temporomandibular joint.

Temporomandibular joint and chewing action

This joint is formed between the cond/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses