Dental Caries

Dental caries is an irreversible microbial disease of the calcified tissues of the teeth, characterized by demineralization of the inorganic portion and destruction of the organic substance of the tooth, which often leads to cavitations. The word caries is derived from the Latin word meaning ‘rot’ or ‘decay’. It is a complex and dynamic process where a multitude of factors initiate and influence the progression of disease. Although effective methods are known for prevention and management of dental caries, it is a major health problem with manifestations persisting throughout life despite treatment. It is seen in all geographic areas in the world and affects persons of both genders in all races, all socioeconomic strata, and every age group. Some stay ‘caries-free’ for unknown reasons (Fig. 9-1). Despite extensive studies for more than a century, many aspects of etiology are still obscure, and efforts at prevention have been partially successful.

Figure 9-1 The caries-resistant and caries-susceptible mouth. Courtesy of A, Dr S Rohini, Chennai and B, Dr N Bhargavi, Department of Conservative Dentistry, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

Epidemiology of Dental Caries

Caries Incidence in Modern Societies

By about the 17th century, there was a significant increase in the total caries experience and a smaller increase in the number of carious lesions involving the interproximal contact areas of teeth, characteristic of the pattern and occurrence of caries in modern population.

Comprehensive Assessment of Dental Caries Prevalence in Modern-day Population

While dental caries is all pervading in highly industrialized societies, the caries experience varies greatly among countries and even within a country. The difference in caries rates noted in different parts of the world are extreme from rates fewer than one decayed, missing and filled (DMF) tooth per person at all ages up to 39 years in Ethiopia (Littleton, 1963) to 60 times greater in Alaska-Aleuts (Russel et al, 1961). Findings from the Interdepartmental Committee on Nutrition for National Defence (ICNND) and WHO studies (Barmes, 1981) indicate that caries prevalence follows definite regional patterns. It is generally lowest (0.5–1.7 DMF) in Asian and African countries and highest (12–18 DMF) in America and other Western countries. Consistently, low to moderate caries rates were found in populations of the Indo-Chinese peninsula, Malaysia, central and southern Thailand, Burma, South Vietnam, mainland China, Taiwan, India and New Guinea.

DMF and def Index

Factors Affecting Caries Prevalence

Gender

Studies indicate that the total caries experience in permanent teeth is greater in females than in males of the same age. This is attributable largely to the fact that the teeth of girls erupt at an earlier age. This time difference is particularly significant during the formative years because teeth have been shown to be maximally susceptible to dental caries immediately after eruption since, the chemical structure of teeth in the immediate post eruptive stage is suboptimal in terms of caries resistance. As teeth are exposed to saliva and constituents in the diet, the outer layers of the tooth take up additional minerals from the oral environment in a process known as posteruptive maturation. This maturation process confers a greater resistance to dental caries on the tooth.

Familial

Siblings of individuals with high caries susceptibility are also generally caries active, whereas siblings of caries immune individuals generally exhibit low caries rates. Children of parents with a low caries experience also tend to have low caries; the converse is true for children whose parents have a high caries rate (Garn et al, 1976). Studies of the dental caries experience in monozygotic and dizygotic twins indicate that concordance for carious sites in monozygotic twins is much higher than in dizygotic twin pairs.

Etiology of Dental Ca ries

The Early Theories

Parasitic Theory

The first to relate microorganisms to caries on a causative basis as early as 1843 was Erdl who described filamentous organisms in the membrane removed from teeth. Shortly thereafter, Ficnus in 1847, a German physician in Dresden, attributed dental caries to ‘denticolae’ the generic term he proposed for decay related microorganisms. Leber and Rottenstein, two German physicians, disseminated the idea that dental caries commenced as a chemical process but that living microorganisms continued the disintegration in both enamel and dentin. In addition to these observations, Clark (1871, 1879), Tomes (1873) and Magitot (1878) concurred that bacteria were essential to caries, although they suggested an exogenous source of the acids. In 1880, Underwood and Miller presented a septic theory with the hypothesis that acid capable of causing decalcification was produced by bacteria feeding on the organic fibrils of dentin. They reported sections of decayed dentin having micrococci as well as oval and rod shaped forms.

Miller’s Chemico-Parasitic Theory or The Acidogenic Theory

The chemico-parasitic theory is a blend of the above mentioned two theories. Willoughby D Miller, an American who was working at the University of Berlin, is probably the best known of the early investigators on dental caries. He published extensively on the results of his studies, beginning in 1882, which culminated in the hypothesis, “Dental decay is a chemico-parasitic process consisting of two stages, the decalcification of enamel, which results in its total destruction and the decalcification of dentin as a preliminary stage, followed by dissolution of the softened residue. In case of enamel; however, the second stage is practically wanting, the decalcification of enamel signifying its total destruction”. The acid, which affects this primary decalcification, is derived from the fermentation of starches and sugar lodged in the retaining centers of the teeth. Miller found that bread, meat and sugar incubated in vitro with saliva at body temperature, produced enough acid within 48 hours to decalcify sound dentin. Subsequently, he isolated numerous microorganisms from the oral cavity, many of which were acidogenic and some were proteolytic. Since a number of these bacterial forms were capable of forming lactic acid, Miller believed that caries was not caused by any single organism, but rather by a variety of microorganisms. He assigned an essential role to three factors in the caries process: the oral microorganisms in acid production and proteolysis; the carbohydrate substrate; and the acid which causes dissolution of tooth minerals. Miller’s chemico-parasitic theory is the backbone of current knowledge and understanding of the etiology of dental caries.

Role of Microorganisms

Many of the earlier workers focused attention on L. acidophilus because it was found with such frequency in caries-susceptible persons that it came to be regarded as of etiologic importance. In 1925, Bunting and Palmerlee reported the bacillary forms in every initial lesion of caries similar to those described by McIntosh and they termed them B. acidophilus. Bunting stated in 1928, so definite is this correlation between B. acidophilus and dental caries that, in the opinion of this group, the presence or absence of B. acidophilus in the mouth constitutes a definite criterion of the activity of dental caries that is more accurate than any clinical estimation could be. Furthermore, it was noted that there was a spontaneous cessation of caries coincident with the disappearance of B. acidophilus from the mouth, either from prophylactic, therapeutic or dietetic control.

Microbial Flora and Dental Caries

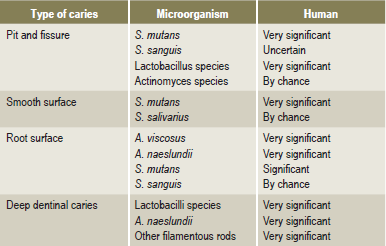

It is uniformly agreed that caries cannot occur without microorganisms. Several organisms have been found capable of inducing carious lesions when used as monocontaminants in gnotobiotic (germ-free) rats. These include the mutans group of streptococci, a Streptococcus salivarius strain, Streptococcus mitior, Streptococcus milleri, Streptococcus oralis, Streptococcus sanguis (different strains), Peptostreptococcus intermedius, Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei, Actinomyces viscosus and Actinomyces naeslundii. In addition, in the same animal system, some streptococcis and lactobacilli such as Lactobacillus fermentum and Streptococcus lactis, were not able to induce caries, suggesting that not all organisms are cariogenic, at the same time caries will not occur even in the complete absence of microorganisms. Different organisms display certain selectivity for the tooth surface they localize and attack (Table 9-1).

Studies in humans are largely based on the mathematical relationship between various streptococci, lactobacilli and dental caries. Available data strongly suggest an active involvement of S. mutans in caries initiation. Strains of S. mutans isolated from humans have proved to be cariogenic in animal studies and S. mutans can almost always be found in plaques over incipient lesions involving pits and fissures or smooth tooth surfaces. Not all studies support a unique or sole relationship between S. mutans and the initiation of caries in humans. The characteristics and properties of some known potentially cariogenic plaque microorganisms are discussed.

Oral Streptococci

The most important substrate for the involvement of S. mutans in the caries process is the disaccharide sucrose. Different pathways by which S. mutans may dissimilate sucrose, are by conversion of sucrose to adhesive extracellular carbohydrate polymers by cell bound and extracellular enzymes. The transport of sucrose into the cell interior is accompanied by direct phosphorylation for energy utilization through the glycolytic pathway, leading to lactic acid production and degradation of sucrose to free glucose and fructose by invertase. The intermediary metabolites from sucrose enter the glycolytic cycle or may be utilized in intracellular polymer synthesis in order to provide a reservoir for energy.

Role of Acids

The exact mechanism of carbohydrate degradation to form acids in the oral cavity by bacterial action is not known. It probably occurs through enzymatic breakdown of the sugar, and the acids formed are chiefly lactic acid, although others such as butyric acid are also formed. Since acid production is dependent upon a series of enzyme systems, methods of decreasing this acid formation by interference with certain enzymes could be an effective strategy to decrease caries.

Role of the Dental Plaque

There is a general agreement that enamel caries begins beneath the dental plaque. The presence of a plaque; however, does not necessarily mean that a carious lesion will develop at that point. Variations in caries formation have been attributed to the nature of the plaque itself, to the saliva or to the tooth. Extensive study of the bacterial flora of the dental plaque has indicated a heterogeneous nature of the structure. Most workers have stressed the presence of filamentous microorganisms, which grow in long interlacing threads and have the property of adhering to smooth enamel surfaces. Smaller bacilli and cocci then become entrapped in this reticular meshwork. Aciduric and acidogenic streptococci and lactobacilli are particularly numerous in this setup. Occasionally, strains of the filamentous organisms are actively acidogenic through carbohydrate fermentation, but this does not appear to be a general feature of this group.

Bibby (1940) studied the characteristics of different strains of filamentous organisms isolated from dental plaques and noted their ability to adhere to smooth surfaces. Blayney and his associates (1942) pointed out that the time required for the development of definite cavitation representing early caries in an intact enamel surface was several months. Hemmens and his coworkers (1946) believed that dental plaque was the most likely starting point for investigations aimed at understanding the earliest stage of enamel caries. They examined numerous plaques from areas of children’s teeth which became carious during the course of investigation. Aciduric streptococci were the organisms most commonly isolated from plaques during the period of caries activity, being present in varying numbers in 86% of the plaques. α-streptococci were isolated from slightly over 50% of the plaques from carious surfaces and from 75% of those from noncarious surfaces. The greatest incidence of occurrence of lactobacilli in plaque was 57%, but these organisms increased in incidence during that period in which the carious lesions were developing.

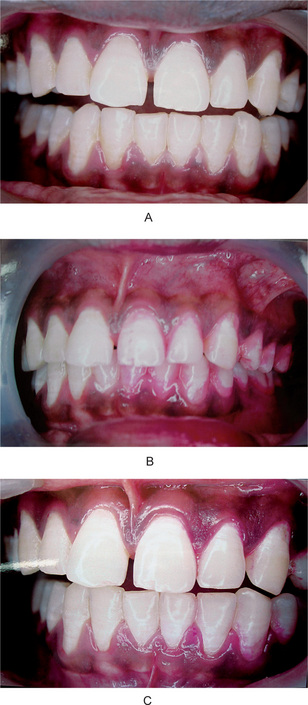

Plaques are classified as supra or subgingival, according to the anatomical area in which they form. Supragingival plaques play an essential role in the pathogenesis of dental caries while marginal and subgingival plaques are responsible for the initiation of periodontal diseases.The amount of plaque can be assessed directly by clinical examination (Fig. 9-2). Often dye solutions, referred to as disclosing agents, are used to stain plaques for visual scoring. Although carious lesions will not develop without plaque, it should be emphasized that plaques can often be relatively innocuous, have buffering capacity and protecting the teeth from exposure to acids present in many foods. However, when plaques contain appreciable proportions of highly acidogenic bacteria such as S. mutans and are exposed to readily fermentable dietary sucrose, they produce sufficient concentrations of acids to demineralise the enamel.

Figure 9-2 Dental plaque.

(A) The appearance of the teeth in all quadrants is similar, although the teeth on one side were not brushed for three days. (B) The dental plaque on the unbrushed teeth becomes obvious after the application of a disclosing solution. (C) Brushing the teeth and reapplying disclosing solution reveals that the plaque, if in an accessible area, is readily removed by brushing Courtesy of Dr L Natarajan and Dr Duliganti Santosh Reddy, Meenakshi Ammal Dental College, Chennai.

Mechanism of Plaque Formation

The pellicle appears as three distinct components. The subsurface component, below the surface of enamel having a dendritic configuration, the 1μm thick surface component closely associated with the surface of the tooth, and a suprasurface portion of 10 μm thickness which has a scalloped appearance. These amorphous organic films on the enamel surface may influence caries formation and bacterial adhesion. The acquired pellicle, like most proteinaceous adsorbed layers, is a membrane that may impart semipermeable properties to the enamel surface.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Etiology of Dental Caries

. Etiology of Dental Caries . Clinical Aspects of Dental Caries

. Clinical Aspects of Dental Caries . Histopathology of Dental Caries

. Histopathology of Dental Caries . Diagnosis of Dental Caries

. Diagnosis of Dental Caries . Methods of Caries Control

. Methods of Caries Control