Introduction to Evidence-Based Decision Making

Jane L. Forrest, Syrene A. Miller, Greg W. Miller and Michael G. Newman

Background and Definition

Using evidence from the medical literature to answer questions, direct clinical action, and guide practice was pioneered at McMaster University, Ontario, Canada, in the 1980s. As clinical research and the publication of findings increased, so did the need to use the medical literature to guide practice. The traditional clinical problem-solving model based on individual experience or the use of information gained by consulting authorities (colleagues or textbooks) gave way to a new methodology for practice and restructured the way in which more effective clinical problem solving should be conducted. This new methodology was termed evidence-based medicine (EBM).12 EBM is defined as “the integration of the best research evidence with our clinical expertise and our patient’s unique values and circumstances.”31

• The methods of generating high-quality evidence, such as randomized controlled trials and other well-designed methods.

• The statistical tools for synthesizing and analyzing the evidence (systematic reviews and meta-analysis).

• The ways for accessing the evidence (electronic databases) and applying it (evidence-based decision making and practice guidelines).9,10

These changes have evolved along with the understanding of what constitutes the evidence and how to minimize sources of bias, quantify the magnitude of benefits and risks, and incorporate patient values.13 “In other words, evidence-based practice is not just a new term for an old concept and as a result of advances, practitioners need (1) more efficient and effective online searching skills to find relevant evidence and (2) critical appraisal skills to rapidly evaluate and sort out what is valid and useful and what is not.”27

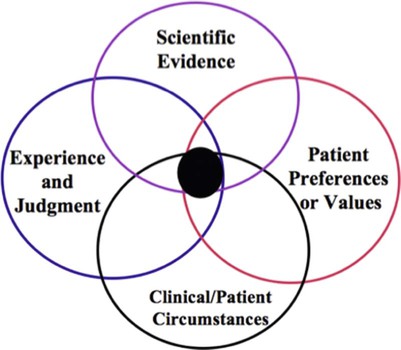

Evidence-based decision making (EBDM) is the formalized process and structure for learning and using the skills for identifying, searching for, and interpreting the results of the best scientific evidence, which is considered in conjunction with the clinician’s experience and judgment, the patient’s preferences and values, and the clinical and patient circumstances when making patient-care decisions. Translating the EBDM process into action is based on the abilities and skills identified in Box 86-1.31

Principles of Evidence-Based Decision Making

The use of current best evidence does not replace clinical expertise or input from the patient but rather provides another dimension to the decision-making process,11,16,19 which is also placed in context with the patient’s clinical circumstances (Figure 86-1). It is this decision-making process that we refer to as “evidence-based decision making” and is not unique to medicine or any specific health discipline; it represents a concise way of referring to the application of evidence to clinical decision making.

EBDM focuses on solving clinical problems and involves two fundamental principles, as follows13:

1. Evidence alone is never sufficient to make a clinical decision.

2. Hierarchies of quality and applicability of evidence exist to guide clinical decision making.

EBDM is a structured process that incorporates a formal set of rules for interpreting the results of clinical research and places a lower value on authority or custom. In contrast to EBDM, traditional decision making relies more on intuition, unsystematic clinical experience, and pathophysiologic rationale.13

Evidence-Based Dentistry

Since the 1990s, the evidence-based movement has continued to advance and is widely accepted among the healthcare professions, with some refining the definition to make it more specific to their area of healthcare. The American Dental Association (ADA) has defined evidence-based dentistry (EBD) as “an approach to oral health care that requires the judicious integration of systematic assessments of clinically relevant scientific evidence, relating to the patient’s oral and medical condition and history, with the dentist’s clinical expertise and the patient’s treatment needs and preferences.”4 They also have established the ADA Center for Evidence-Based Dentistry™ (www.ebd.ada.org) to facilitate the integration of EBD into clinical practice.

The ADA’s definition is now incorporated in the Accreditation Standards for Dental Education Programs.3 Dental schools are expected to develop specific core competencies that focus on the need for graduates to become critical thinkers, problem solvers, and consumers of current research findings to enable them to become lifelong learners. The accreditation standards require learning EBDM skills so that graduates are competent in being able to find, evaluate, and incorporate current evidence into their decision making.3

Evidence-Based Decision-Making Process and Skills

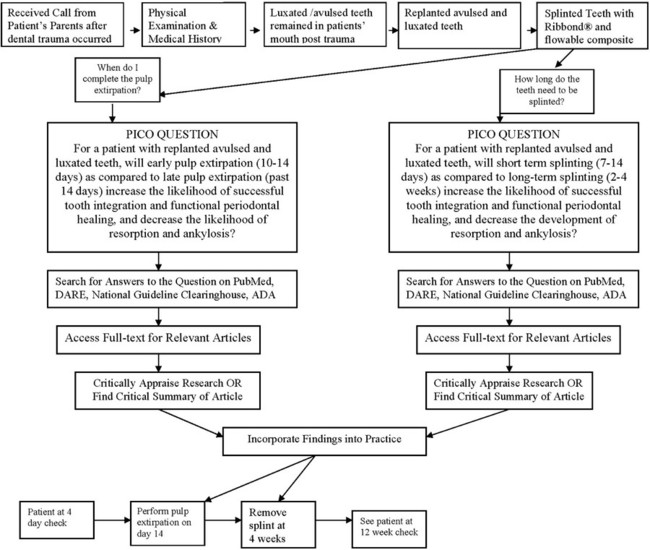

The growth of evidence-based practice has been made possible through the development of online scientific databases such as MEDLINE (PubMed) and web-based software, along with the use of computers and mobile devices, for example, smart phones, that enable users to quickly access relevant clinical evidence from almost anywhere. This combination of technology and good evidence allows healthcare professionals to apply the benefits from clinical research to patient care.29 EBDM recognizes that clinicians can never be completely current with all conditions, medications, materials, or available products, and it provides a mechanism for assimilating current research findings into everyday practice to answer questions and to stay current with innovations in dentistry. Translating the EBDM process into action is based on the abilities and skills identified in Box 86-1.31 This is illustrated clearly in a real patient case scenario that is introduced in Box 86-2 and used throughout the chapter.

Asking Good Questions: The PICO Process

Converting information needs and problems into clinical questions is a difficult skill to learn, but it is fundamental to evidence-based practice. The EBDM process almost always begins with a patient question or problem. A “well-built” question should include four parts that identify the patient problem or population (P), intervention (I), comparison (C), and outcome(s) (O), referred to as PICO.31 Once these four components are clearly and succinctly identified, the following format can be used to structure the question:

The formality of using PICO to frame the question serves two key purposes, as follows:

1. PICO forces the clinician to focus on what he or she and the patient believe to be the most important single issue and outcome.

2. PICO facilitates the next step in the process, the computerized search, by identifying key terms that will be used in the search.31

The conversion of information needs into a clinical question is demonstrated using the case scenario from Box 86-2. Two separate PICO questions were written as follows:

1. For a patient with replanted avulsed and luxated teeth (P), will early pulp extirpation (10 to 14 days) (I) as compared to late pulp extirpation (past 14 days) (C) increase the likelihood of successful tooth integration and functional periodontal healing, and decrease the likelihood of resorption and ankylosis (O)?

2. For a patient with replanted avulsed and luxated teeth (P), will short-term splinting (7 to 14 days) (I) as compared to long-term splinting (2 to 4 weeks) (C) increase the likelihood of successful tooth integration and functional periodontal healing, and decrease the development of resorption and ankylosis (O)?

Prior to conducting a computerized search, it is important to have an understanding of the types of research study methodologies and the appropriate methodology that relates to different types of clinical questions. The methodology, in turn, relates to the levels of evidence. Table 86-1 shows these relationships.

TABLE 86-1

Type of Question Related to Type of Methodology and Levels of Evidence

| Type of Question | Methodology of Choice28 | Question Focus23 |

| Therapy, prevention | Meta-analyses (MA) or systematic review (SR) of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) SR of cohort studies |

Study effect of therapy or test on real patients; allows for comparison between intervention and control groups; largest volume of evidence-based literature. |

| Diagnosis | MA or SR of controlled trials (prospective cohort study) Controlled trial (Prospective: compare tests with a reference or “gold standard” test.) |

Measures reliability of a particular diagnostic measure for a disease against the “gold standard” diagnostic measure for the same disease. |

| Etiology, causation, harm | MA or SR of cohort studies Cohort study (Prospective data collection with formal control group) |

Compares a group exposed to a particular agent with an unexposed group; important for understanding prevention and control of disease. |

| Prognosis | MA or SR of inception cohort studies Inception cohort study (All have disease but free of the outcome of interest.) Retrospective cohort |

Follows progression of a group with a particular disease and compares with a group without the disease. |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses