CHAPTER 8 Tumors of the Oral Soft Tissues and Cysts and Tumors of the Bone

BENIGN TUMORS OF THE ORAL SOFT TISSUE

SQUAMOUS PAPILLOMA AND VERRUCA VULGARIS

The squamous papilloma is a relatively common, benign neoplasm that arises from the surface epithelium. It is typically an exophytic lesion whose surface may vary from cauliflower-like to finger-like in appearance, and although it is generally a pedunculated lesion, it may arise from a sessile base. Although the average age of occurrence is in the fourth decade of life, nearly 20% of cases have been noted to occur before 20 years of age.1,2 The most common sites of occurrence appear to be the tongue and palatal complex, followed by the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. This lesion is also seen with some frequency on the mandibular alveolar ridge, floor of the mouth, and retromolar pad regions.2

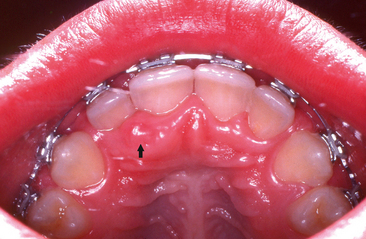

Oral verruca vulgaris, or oral warts, are exophytic papillomatous lesions indistinguishable clinically from oral squamous cell papillomas. Like their skin counterpart, the common wart (verruca vulgaris), they are a viral disorder associated with the human papillomavirus (HPV) and may be spread to the oral cavity in children through autoinoculation by finger or thumb sucking (Fig. 8-1). According to two reviews of HPV-associated diseases of oral mucosa, types 2 and 57 were most commonly found.3,4 DNA types 6, 11, and 16 have also been demonstrated in oral verrucae.5,6

Although the histopathologic differences between squamous papilloma and verruca vulgaris are subtle, these lesions are distinguishable from one another. Histologically, the papilloma is seen as a proliferation of the spinous cell layer in a papillary pattern, often with hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and basilar hyperplasia. Mitotic figures may be prominent. The supporting fibrous connective tissue stroma often contains prominent numbers of small blood vessels as well as an inflammatory cell infiltrate. HPV may, however, be seen in squamous cell papillomas. In 1982 the presence of HPV genus-specific antigens was demonstrated in two of five multiple papillomas.7 In a subsequent review of the world literature analyzing 223 papillomas, the overall detection rate for HPV DNA was 49.8% with the most prevalent HPV types being HPV 6 and 11.4 HPV types 16 and 18 have also been detected in some squamous cell papillomas.8

The presence of papillomatosis often with convergence of rete ridges centrally, hyperkeratosis (either hyperparakeratosis or hyperorthokeratosis, or both) a coarse keratohyalin granular cell layer and vacuolated cells with pyknotic nuclei (koilocytes) may be used to differentiate verruca vulgaris from a squamous papilloma. Hence, from the above discussion both squamous papilloma and verrucous vulgaris should probably be considered benign, virus-induced epithelial hyperplasias and the identification of HPV does not appear to offer any diagnostic advantage because the histopathologic features alone allow for differentiation of one from the other.9

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA, PERIPHERAL OSSIFYING FIBROMA, PERIPHERAL ODONTOGENIC FIBROMA (WHO TYPE), AND PERIPHERAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA

Pyogenic Granuloma

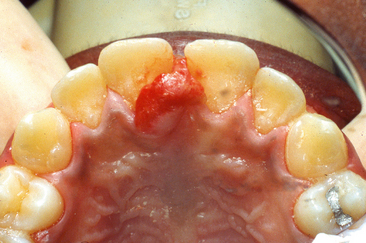

Clinically the pyogenic granuloma is a raised lesion on either a sessile or a pedunculated base. Its surface may have a smooth, lobulated, or, occasionally, warty appearance that is erythematous and often ulcerated (Fig. 8-2). Depending on the age of the lesion, the texture varies from soft to firm and is suggestive of an ulcerated fibroma. Because of the pronounced vascularity of these lesions, they often bleed easily when probed. A review of pyogenic granulomas of the oral cavity revealed a 65% to 70% incidence of occurrence on the gingiva, most commonly the maxillary anterior labial gingiva, followed by the lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, mucolabial or mucobuccal fold, and alveolar mucosa of edentulous areas.10 Twenty-seven percent of cases in this series of 46 patients were in individuals younger than 20 years of age. Another review of 38 cases reported an age range of 5 to 75 years (mean age, 33 years) with the most frequent site of occurrence also being on the gingiva (74%).10,11

PERIPHERAL OSSIFYING FIBROMA AND PERIPHERAL ODONTOGENIC FIBROMA (WHO TYPE)

Peripheral Ossifying Fibroma

The peripheral ossifying fibroma is a reactive lesion believed to be of periodontal ligament origin that occurs exclusively on the gingiva. In the largest series of cases, 50% of the lesions were noted to occur in individuals between 5 and 25 years of age, with the peak incidence at 13 years.12 The lesions were approximately equally divided between the maxilla and the mandible, with more than 80% of the lesions in both jaws occurring anterior to the molar area.

Histologically the peripheral ossifying fibroma demonstrates a proliferation of plump fibroblasts in a characteristic stroma of delicate, interlacing collagen fibrils. Osteoid and calcified material varying from dystrophic calcification to spicules of lamellar bone may be found in the lesion. The surface epithelium is often ulcerated. Although simple surgical excision is the treatment of choice, recurrences are not uncommon and were reported by Cundiff and by Eversole and Rovin in 16% and 20% of cases, respectively.12,13 In a more recent study of 134 cases of peripheral ossifying fibroma in patients aged 1 to 19 years, the overall recurrence rate was 8%. However, this was thought to represent the minimum rate of recurrence in that no attempt was made to determine how many patients with or without recurrent lesions were followed clinically, and if so, for how long.14

Peripheral Odontogenic Fibroma (WHO type)

Previously, the terms peripheral ossifying fibroma and peripheral odontogenic fibroma were used synonymously, which introduced considerable confusion into the literature. To clarify the confusion, the term peripheral odontogenic fibroma (World Health Organization [WHO] type) was proposed to denote the rare peripheral counterpart of the central odontogenic fibroma (WHO type), and the term peripheral ossifying fibroma was proposed to be retained and used to denote the relatively common reactive gingival lesion.15 Clinically the peripheral odontogenic fibroma (WHO type) must be considered in the differential diagnosis of dome-shaped or nodular, usually nonulcerated, growths on the gingiva.

It is a rare odontogenic tumor characterized by a fibrous or fibromyxomatous stroma containing varying numbers of islands and strands of odontogenic epithelium. Cementum-like, bone-like, or dentinoid material may be present. Its age at presentation is strikingly similar to the peripheral ossifying fibroma. Even though treatment consists of local surgical excision, in one study recurrence was noted in 7 of 18 cases for which follow-up information was obtained.16

Peripheral Giant Cell Granuloma

The peripheral giant cell granuloma, like the peripheral ossifying fibroma, is a lesion unique to the oral cavity, occurring only on the gingiva. Unlike the peripheral ossifying fibroma, however, it may occur on the alveolar mucosa of edentulous areas. Like the pyogenic granuloma and peripheral ossifying fibroma, the peripheral giant cell granuloma may represent an unusual response to tissue injury. It is distinguishable from the pyogenic granuloma and peripheral ossifying fibroma only on the basis of its unique histomorphology, which is essentially identical to that of the central giant cell granuloma that is discussed later in this chapter. In a review of 720 cases, 33% were seen in patients younger than 20 years of age, which concurs with the findings of another study in which 33 of 97 cases (34%) occurred in individuals between 5 and 15 years of age.17,18 There is a nearly 2:1 predilection of females to males, with the mandible being involved more often than the maxilla. Although it is rare, cervical root resorption may be seen in association with a peripheral giant cell granuloma.19

NEUROFIBROMA AND NEUROFIBROMATOSIS (VON RECKLINGHAUSEN’S DISEASE)

As previously noted, the NF1 gene is a tumorsuppressor gene, and thus patients with neurofibromatosis are at increased risk of developing benign and malignant tumors. Neurofibromatosis is a progressive condition with different presentations occurring at specific times with some complications worsening over time. While cutaneous or dermal neurofibromas are considered one of the characteristic features of this disorder and may appear in childhood, they more commonly develop in teenagers or adults. Although malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors may be noted in pediatric patients with NF1, they usually develop in adulthood and are heralded by the presence of pain or rapid growth arising in a plexiform or deep nodular neurofibroma.20

Intraorally, neurofibromas may present as nodular lesions on either a sessile or pedunculated base, often with a normal, pink mucosal color (Fig. 8-3); as a diffuse, ill-defined swelling with a firm to doughy consistency; or as a diffuse, noncompressible mass. They are most frequently found on the tongue and buccal mucosa but occasionally present as intraosseous lesions, which occur most commonly in the posterior mandible (Fig. 8-4).

The most common radiographic findings include an increase in bone density, enlarged mandibular foramen, lateral bowing of the mandibular ramus, increase in dimensions of the coronoid notch, and decrease in the mandibular angle.21 Computed tomographic scans may reveal findings such as enlargement of the mandibular foramen and concavity of the medial surface of the ramus.

Solitary lesions are best treated by simple surgical excision and show little propensity for recurrence. Surgical excision of diffuse neurofibromas is difficult because of their diffuse, infiltrating nature. Plexiform neurofibromas are also difficult to treat in that they have a tendency to grow along the course of a nerve, which results in frequent recurrences. It has been noted that (1) children younger than 10 years of age, (2) children with plexiform neurofibromas in the head, face, and neck, and (3) those with tumors that cannot be almost completely removed are at particular risk for progression of their lesions.22

HEMANGIOMA

Vascular anomalies are commonly encountered lesions of childhood and may be divided into hemangiomas and vascular malformations.23 Hemangiomas are differentiated from vascular malformations as they demonstrate proliferative activity while vascular malformations grow commensurately with the child.24 The hemangioma is a common, benign, vasoformative tumor that frequently occurs in the head and neck in children. It is generally believed to be hamartomatous rather than neoplastic in nature. Most hemangiomas are either present at birth or develop within the first year of life. It is believed that even those lesions that do not appear until adult life may have been present but not clinically evident until they began to enlarge.

Vascular malformations most frequently involve the skin but also may affect visceral organs or bone. They may be categorized as fast-flow lesions and slow-flow lesions.25 Fast flow lesions include arterial malformations, arteriovenous malformations, and arteriovenous fistulas. Slow-flow lesions include capillary malformations, lymphatic malformations, and venous malformations. Vascular malformations of the mandible (i.e., arteriovenous malformations or central hemangioma of the mandible as they were sometimes called) are potentially dangerous in that a biopsy or simple event such as a tooth extraction may lead to a catastrophic hemorrhage possibly leading to death.26 These lesions may be asymptomatic, picked up only as incidental radiographic findings, or they may cause pain and swelling. They are typically well-circumscribed radiolucent lesions with no characteristic radiographic pattern to denote their underlying nature. Occasionally, loose or displaced teeth may be seen. Arteriovenous malformations bear a radiographic similarity to any number of other relatively wellcircumscribed unilocular or multilocular radiolucent lesions in the jaws. Therefore it is advisable to aspirate such lesions with a needle before surgery or dental extraction to avoid the possibility of severe blood loss or exsanguination caused by the inability to control the resultant profuse bleeding.

LYMPHANGIOMA

Lymphangiomas are relatively rare benign congenital tumors of the lymphatic system. Even though the embryologic events leading to their development remain unclear, they are thought to arise as a benign hamartomatous proliferation of sequestered lymphatic rests. Forming along tissue planes or penetrating adjacent tissue, they become canalized and, in the congenital absence of venous drainage, accumulate fluid. The head and neck region is most commonly involved with up to two thirds of cases being present at birth and as many as 90% being present by the second year of life; a small number may not be manifest for a number of years.27

Lymphangiomas are classified on a histologic basis into three types: capillary lymphangiomas, cavernous lymphangiomas, and cystic hygroma. The capillary lymphangioma is typically composed of a proliferation of thin-walled, endothelium-lined channels primarily devoid of erythrocytes. The cavernous lymphangioma is characterized by the presence of dilated sinusoidal endothelium-lined vascular channels devoid of erythrocytes. The cystic hygroma is a macroscopic form of the cavernous lymphangioma, with large sinusoidal spaces lined with a single layer of endothelial cells that form multilocular cystic masses of varying sizes. Lymphangiomas of the oral soft tissues occur most commonly on the tongue, lips, and buccal mucosa. They are often elevated and nodular in appearance and may have the same color as the surrounding mucosa. Treatment is generally not indicated for small oral mucosal lymphangiomas; partial or complete spontaneous involution is occasionally noted.

CONGENITAL EPULIS (GINGIVAL GRANULAR CELL LESION) OF THE NEWBORN

The congenital epulis of the newborn is a rare lesion of uncertain histogenesis that occurs exclusively in newborn infants, chiefly on the maxillary anterior alveolar ridge and less commonly on the mandibular anterior alveolar ridge. Although usually solitary lesions, they may be multiple, most often affecting both the maxilla and mandible although rare simultaneous occurrence of lesions on the maxillary anterior alveolar ridge and tongue have been reported. Clinically the lesion presents at birth as a pink, smooth to lobulated, pedunculated mass that may vary in size from a few millimeters to more than 7 cm in diameter. More than 90% of cases occur in girls (Fig. 8-5).

While typically considered a lesion of uncertain histogenesis, immunohistochemical studies have revealed strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining for neuronspecific enolase and vimentin, which suggests that the congenital epulis may be derived from uncommitted nerve-related mesenchymal cells.28

Although histologic similarities to the granular cell tumor have long been noted, the epithelium over the congenital epulis is generally thin without rete ridge formation, whereas the granular cell tumor is characterized by pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying epithelium; distinct differences are obvious on both ultrastructural and immunohistochemical evaluation. One differentiating factor between the congenital epulis and granular cell tumor tumors is the absence of S100 in the former and its presence in the latter lesion.29

MUCOCELE

A mucocele may be located either in the superficial mucosa, where it is typically seen as a fluid-filled vesicle or blister (Fig. 8-6), or deep within the connective tissue as a fluctuant nodule with the overlying mucosa normal in color. There may be spontaneous drainage of the inspissated mucin with temporary resolution, especially in superficial lesions, and subsequent recurrence as the mucous saliva continues to drain into the connective tissue at the site of the torn duct. Fibrosis may be observed over the surface of long-standing lesions where chronic periodic drainage has taken place.

RANULA

Ranulas are typically slowly enlarging, fluctuant masses occurring to one side of the midline of the floor of the mouth and are so named because of their resemblance to the bloated underside of a frog’s belly (Fig. 8-7). Lesions are usually treated by marsupialization, with occasional recurrence being noted. Chronic recurrence may require excision of the entire involved gland.

BENIGN TUMORS OF BONE

FIBROUS DYSPLASIA

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia tends to develop early in life with lesions being detected late in the first and early second decades.30 It is seen with approximately equal frequency in males and females, with the maxilla being involved more frequently than the mandible. Maxillary involvement can be an especially serious form of the disease, frequently involving contiguous bones across suture lines, including the maxillary sinus, floor of the orbit, sphenoid bone, base of the skull, and occiput. This form of the disease has been called craniofacial fibrous dysplasia and is not truly monostotic in its nature.

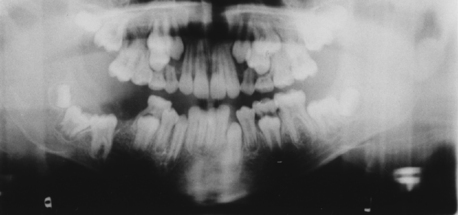

Radiographically, maxillary lesions most often show a ground-glass appearance of the bone, whereas mandibular lesions usually show either a ground-glass or a mixed radiolucent-radiopaque appearance (Fig. 8-8). Their borders are typically poorly defined, except for the anterior portion of some maxillary lesions, which may appear to be well circumscribed. Divergence of roots may be noted, and in children in whom developing permanent teeth are present there may be displacement of teeth with noneruption (see Fig. 8-8). Other potential distinguishing radiographic findings include superior displacement of the mandibular canal and a fingerprint bone pattern as well as displacement of the maxillary sinus cortex, alteration of the lamina dura because of the abnormal bone pattern, and narrowing of the periodontal ligament space.31

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the jaws is typically a slow-growing, painless, progressive enlargement of bone whose growth pattern often stabilizes with time as maturation in skeletal growth is reached. Conservative therapy is indicated because of the benign nature of this lesion and because surgically the margins are ill defined and blend into the surrounding normal bone. Surgery, chiefly in the form of osseous recontouring, should be considered only when there is functional or significant cosmetic deformity and then usually only after stabilization of the disease process. Because this is a benign lesion of bone, radiation therapy is contraindicated because of the possibility of development of a postradiation sarcoma in the area. In symptomatic cases in which pain control and disease stabilization are needed, bisphosphonates have been used, resulting in pain relief and, in a number of patients, disease stabilization as well.32 Little, however, is known about the long-term skeletal effects of childhood bisphosphonate use and it has been recommended that its use be limited to experienced pediatric units.32

OSSIFYING AND CEMENTIFYING FIBROMA

The ossifying fibroma may be entirely asymptomatic, being discovered on routine radiographic examination, or may present as a painless expansion of bone. Radiographically the ossifying fibroma is a well-circumscribed lesion, often with a well-demarcated sclerotic border (Fig. 8-9). Beyond this, the radiographic features are quite variable.33 It most frequently presents as a unilocular radiolucency with or without radiopaque foci, which may be superimposed over teeth, may be interposed between contiguous teeth, or may reside in edentulous regions. Aggressively expansile lesions with or without radiopaque foci as well as multilocular expansile lesions may also be noted. Tooth displacement or divergence of roots of teeth and/or root resorption may be seen with varying degrees of frequency with tooth displacement or root divergence being reported in from 17% to 33% of cases and root resorption being seen between 11% and 44% of the time.33,34 Cortical thinning and bony expansion with clinical deformity have been reported in as many as 91% of cases.

Initial treatment is by enucleation or curettage where possible, with the frequency of recurrence varying from 0% to 28%.33,35

JUVENILE OSSIFYING FIBROMA

The term juvenile ossifying fibroma (JOF), also known as juvenile active ossifying fibroma and juvenile aggressive ossifying fibroma, encompasses two distinct clinicopathologic variants of ossifying fibroma involving the craniofacial bones: the trabecular juvenile ossifying fibroma (TrJOF) and the psammomatoid juvenile ossifying fibroma (PsJOF). The TrJOF affects both the maxilla and the mandible with the maxilla being involved slightly more frequently.36 Occurrence in extragnathic locations is extremely rare.30 The reported mean age ranges from 8{½} to 12 years (range, 2 to 12 years). The PsJOF was noted to occur predominantly in the sinonasal and orbital bones in patients with a mean age range of 16 to 33 years (range, 3 months to 72 years). Aggressive growth was noted to occur in some cases of both types with a high recurrence rate after excision (30% to 56% of cases). It has been proposed that despite some similarities in biologic behavior, differences in histologic, demographic, and clinical presentation between PsJOF and TrJOF warrants their se/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses