Chapter 8

Success and Failure

Aim

To outline minimalist and more stringent definitions of endodontic success, review factors affecting outcome and develop a rational basis for evaluating treatment at intervals after its completion.

Outcome

After studying this chapter, the reader should have a clearer understanding of factors associated with successful root canal treatment; the signs of progress at intervals after treatment; and the consequences of inadequate infection control.

Defining Outcome

Where you stand on an issue depends on where you sit. Patients, clinicians, academics and healthcare organisations all have an interest in successful therapies, including root canal treatment. Whilst clinical academics usually develop “official” definitions of success and failure, everyone has a working understanding of what they consider acceptable. This can range from a minimalist “uncomplaining patient with tooth still present” to a stringent “histological resolution of inflammation and return of tissues to pristine health”. Both extremes may be unreasonable.

Minimalist Definitions of Success

Root canal treatments are often provided for teeth with painful symptoms, but equal numbers are provided for uncomplaining patients, unaware of their necrotic pulp and apical periodontitis. If treatment is offered to prevent and cure disease, it must do more than simply preserve a diseased status quo. Emergence of apical periodontitis, or failure of it to diminish or heal after root canal treatment can only mean that the aetiological agents were inadequately managed and that treatment did not meet its objectives (Fig 8-1).

Fig 8-1 A symptom-free case, but can this really represent success?

Stringent Definitions of Success

Histological monitoring of success is equally unrealistic. Even if they were justified, biopsy results would be disappointing, with few treated teeth completely free of periapical inflammatory cells.

Official Definitions

These try to strike a rational middle ground, embracing patient comfort and function as well as reasonable evidence of healing:

-

No pain, swelling or other symptoms of endodontic origin.

-

No sinus tract of endodontic origin, either through the mucosa or through the periodontal ligament.

-

No limitation of chewing function.

-

Radiographic evidence of a normal periodontal ligament space around the root.

Guidelines consistently note that a symptom-free periapical lesion which remains unchanged or only diminishes in size cannot be counted as success and most commonly demands further review if not further treatment.

Factors Associated with Success and Failure

Achieving a successful outcome in the terms defined can be influenced by the:

-

preoperative condition of the patient and tooth

-

treatment provided

-

management and maintenance of the tooth after treatment.

Preoperative Condition of the Patient and Tooth

Age, gender and health of the patient

Since apical periodontitis represents a balance between intracanal infection and host defences, it might be assumed that host factors would exert a major influence on treatment outcome. Surprisingly, there is little indication that they do, and there are consequently few contraindications for root canal treatment. However, severely immunocompromised and patients about to undergo radiotherapy to the jaws may not heal as quickly and predictably as others, and extraction with medical liaison is usually the preferred treatment for apical periodontitis in such cases.

Presence of apical periodontitis

This is the single most important factor in studies of endodontic outcome.

-

Teeth without apical periodontitis are more likely to maintain apical health after treatment than teeth with apical periodontitis are likely completely to heal.

-

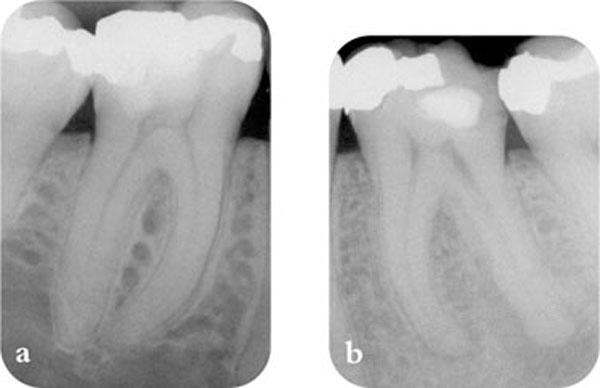

Since apical status is important in defining success, teeth without apical periodontitis (irreversible pulpitis cases) are approximately 25% more likely to be successful than cases with pulp necrosis and established apical periodontitis (Fig 8-2 a,b).

Fig 8-2 (a) Root canal treatment of this tooth is more likely to be successful in terms of periapical health at review than (b).

There are few studies to show that root canal treatment restores comfort and function more predictably for teeth with or without apical periodontitis.

Size of periapical lesion

Periapical lesions can develop over many years. Lesions >5mm diameter may be expected to fill with bone more slowly than those <5mm diameter. There are, of course, exceptions (Fig 1-8), and large lesions can heal by soft-tissue scarring which may be difficult to distinguish from persistent inflammation.

Condition and position of the tooth

Pulpectomy and root canal treatment predictably relieve symptoms of pulpitis and heal apical periodontitis. There is no convincing evidence that molars and their surrounding tissues are less responsive to treatment than any other tooth. However, factors which may compromise treatment such as:

-

coronal breakdown

-

anatomical complexity

-

difficult access

-

calcification

-

curvature

-

cracks

may be more prevalent or multiply represented in multi-rooted posterior teeth, making their treatment appear less predictable.

Nature of the canal flora or periapical lesion

Most apical lesions are sustained by infections which are disrupted or eliminated by canal preparation. However, there are instances of:

-

intracanal infection resistant to normal measures

-

extraradicular infections inaccessible to routine procedures

-

periapical lesions independent of intracanal infection (see Chapter 1).

These probably represent less than 5% of all cases with apical periodontitis and diagnostics are currently unable to detect them. The smell of a root canal and the appearance of a lesion’s margins (cort/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses