Chapter 8

Smoking and Tobacco Use Cessation

The habitual use of tobacco by smoking (cigarettes, cigars, pipes) or as smokeless products (chewing tobacco, snuff) typically constitutes an addictive disease that continues to be a major public health problem. Smoking is the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the United States, resulting in an estimated 443,000 premature deaths per year and $193 billion in direct health care costs and lost productivity.< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />1 In addition, more than 8.6 million persons are disabled as a consequence of smoking-related diseases.2 Smoking causes more than twice as many deaths as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), alcohol abuse, motor vehicle crashes, illicit drug use, and suicide combined.3 On average, smokers die 10 years earlier than nonsmokers.4

With their perspective on the health of the oral cavity and upper airway, directly observed in routine clinical practice, dentists are in a unique position to provide assessment, advice, and referral for smoking cessation. This chapter summarizes current knowledge applicable to this role for the dental health professional, with content encompassing the following topics:

• The physical and psychological effects of smoking and tobacco use

• The basic principles involved in a smoking cessation program

• Approaches used for smoking cessation and the success rates for each

• Available nicotine replacement products and how they are used

• Drugs used in smoking cessation programs and how they are used

• The basics of counseling and other support for the patient who wishes to stop smoking

Systemic and Oral Effects of Smoking

Cigarette smoking is a major risk factor for stroke, myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease, aortic aneurysm, and sudden death. It is the leading cause of lung disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, and lung cancer. It also is strongly linked to cancers of the mouth, esophagus, stomach, pancreas, cervix, kidney, colon, and bladder. Other effects include premature skin aging and an increased risk for cataracts. Cigar and pipe smokers are subject to addictive and general health risks similar to those for cigarette smokers, although pipe and cigar users typically do not inhale. Oral effects of smoking include squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 8-1), leukoplakia (Figure 8-2), nicotine stomatitis (Figure 8-3), smoker’s melanosis, hairy tongue (Figure 8-4), and halitosis. Smoking increases the risk of failure of intraosseous implants and the risk of dry socket, and it also is associated with impaired wound healing.5,6

The adverse effects of smokeless tobacco consist primarily of addiction and pathologic changes in the oral mucosa, including squamous cell carcinoma, tobacco or snuff dipper’s pouch (Figure 8-5), verrucous carcinoma (Figure 8-6), gingival recession (Figure 8-7), periodontitis, and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (Figure 8-8). The senses of taste and smell are diminished as well. Evidence suggests that smokeless tobacco use may be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes and pancreatic cancer.7,8

Health care professionals must be vigilant in identifying those patients who use tobacco, with goals of encouraging them to stop smoking and assisting them in their efforts. Studies indicate that 70% of smokers want to quit smoking.9 For every smoker who successfully quits, however, many more do not succeed. Tobacco dependence is a chronic condition that often requires repeated attempts at intervention. Smokers typically fail multiple attempts to quit before they achieve success.

Scope of the Problem

It is estimated that approximately 20.6% (46 million) of adults older than 18 years of age in the United States are current smokers, and that of these, 78.1% (36.4 million) smoke every day.10 Thus, in a dental practice of 2000 patients, approximately 400 of them will be smokers. The overall prevalence of cigarette smoking is lower than the 21.6% rate reported in 2003 and is significantly lower than the 22.5% rate reported in 2002; however, these declines have stalled in the past 5 years, barely dropping from 20.9% in 2005 to 20.6% in 2009.10 From 1993 through 2004, the percentage of daily smokers who smoked more than 25 cigarettes per day (CPD) (i.e., heavy smokers) decreased steadily, from 19.1% to 12.1%. The mean CPD count among daily smokers was 19.6 in 1993, falling to 16.8 in 2004. Although this trend is encouraging, the problem continues to be a serious public health issue.

The prevalence of current cigarette smoking varies substantially across population subgroups.10 Current smoking rates are higher among men (23.5%) than among women (17.9%). Among racial and ethnic populations, Asians (12%) and Hispanics (14.5%) have the lowest prevalence of current smoking; multiracial persons have the highest (29.5%), followed by Native Americans and Native Alaskans (23.2%), non-Hispanic whites (22.1%), and non-Hispanic blacks (21.3%). By education level, current smoking is most prevalent among adults who have earned a graduate educational development (GED) diploma (49.1%) and lowest in those with a graduate degree (5.6%). Persons older than 65 years of age exhibit the lowest prevalence of current cigarette smoking (9.5%) among all adults. Current smoking prevalence is higher among adults who live below the poverty level (31.1%) than among those at or above the poverty level (19.4%). Smoking prevalence also varies significantly by state or other geographic area, ranging from 9.8% in Utah to 25.6% in Kentucky and West Virginia.

The use of smokeless tobacco is seen primarily in men and adolescent boys who are rural residents of southern and western states; in whites and Native Americans and Native Alaskans; and in persons with lower levels of education.11 Prevalence is highest in Wyoming (9.1%), West Virginia (8.5%), and Mississippi (7.5%) and lowest in California (1.3%), the District of Columbia (1.5%), Massachusetts (1.5%), and Rhode Island (1.5%).12 The use of smokeless tobacco became a national public health issue in the early to mid-1980s, when tobacco companies aggressively marketed their products by targeting young people. This practice was halted as a result of Congressional legislation and resulted in a gradual decline in prevalence, from 6.1% in 1987 to 4.5% in 2000. Of historical interest is the recommendation by some health care professionals that smokeless tobacco be promoted to cigarette smokers as a safer alternative for those who are having difficulty quitting smoking (harm reduction); current evidence questions the efficacy of such a practice.13–15

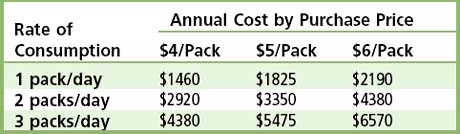

The economic impact of smoking is staggering. On a national level, the U.S. Public Health Service estimates a total annual cost of $50 billion for the treatment of patients with smoking-related disease, in addition to $47 billion in lost wages and productivity. For the individual smoker, the economic impact of smoking can be substantial, especially because as noted, smoking is more common among persons with limited financial resources. Smokers pay more for life and health insurance, the resale value of their cars and homes is decreased, and they have increased costs for dry cleaning, and of course medical and dental care. The cost of a pack of cigarettes varies, reflecting differences in excise taxes levied by states, counties, and cities, in addition to that imposed by the federal government.16 The current federal excise tax is $1.01/pack. State-imposed cigarette tax ranges from a high of $2.75/pack (in New York) to a low of $0.07/pack (in South Carolina); the national average is $1.20/pack. Additional county and city taxes may add as much as $1.50 more (in New York City). States may have additional miscellaneous administrative fees. When all taxes and fees are taken into consideration, the average cost of a pack of cigarettes in the United States is higher than $5. Table 8-1 presents calculations of the average annual costs incurred by cigarette smokers, depending on how many packs are smoked per day and the cost of a pack of cigarettes. In comparison, the average daily costs for smoking cessation products are estimated to be $3.91 for the patch, $5.81 for the gum, $4.98 for the lozenges, and $4.30 for sustained-release bupropion.17 These costs may vary, depending on the strengths used, and unlike cigarettes, which are purchased on a regular basis, these products will be used for only a limited period of time (several weeks or months). These cost comparisons should be brought forward when patients express concern about the cost of purchasing nicotine replacement products or medications.

Benefits of Quitting

People who quit smoking live longer than those who continue to smoke, because the chances for development of smoking-related fatal diseases begin to lessen immediately with cessation of smoking.18 The extent to which a smoker’s risk is reduced by quitting is dependent on several factors, including number of years as a smoker, number of cigarettes smoked per day, and presence or absence of disease at the time of quitting. Data show that persons who quit smoking before the age of 50 have half the risk of dying in the next 15 years compared with those who continue to smoke. Risks of dying of lung cancer are 22 times higher among male smokers and 12 times higher among female smokers than in those who have never smoked. The risk of dying of coronary heart disease for smokers is double that for lifetime nonsmokers, as is the risk of dying from a stroke. Smoking increases the risk for development of COPD by accelerating the age-related decline in lung function. Box 8-1 lists short-term and long-term benefits of smoking cessation.

Box 8-1 Benefits of Quitting Smoking

Long-Term Benefits—Timeline*

• 20 minutes after quitting: Heart rate drops.

• 12 hours after quitting: Carbon monoxide level in the blood drops to normal.

• 2 weeks to 3 months after quitting: Circulation improves and lung function increases.

• 1 to 9 months after quitting: Coughing and shortness of breath decrease; cilia—tiny hairlike structures that move mucus out of the lungs—regain normal function, increasing the ability to handle mucus, clean the lungs, and reduce the risk of infection.

• 1 year after quitting: The excess risk of coronary heart disease is half that of a smoker’s.

• 5 years after quitting: Stroke risk is reduced to that of a nonsmoker 5 to 15 years after quitting.

/>

Only gold members can continue reading.

Log In or

Register to continue