Chapter 8

A Surgical Alternative

Aim

To outline the rationale and describe step-by-step the apicectomy and root-end filling procedure.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter, the practitioner should be familiar with the planning process, preparatory measures and the practical procedure of apicectomy and root-end filling in managing endodontic failure.

Introduction

Surgical retreatment encompasses a number of procedures, referred to synonymously as:

-

periapical curettage/periradicular curettage

-

apicectomy/root end resection/apical resection

-

root-end filling/retrograde filling

-

surgical repair

-

root resection/root amputation

-

hemisection/bicuspidization.

As it is beyond the remit of this book to cover all these procedures, the focus of this chapter will be on apicectomy and root-end filling – the most frequently performed endodontic surgical retreatment procedure. In this chapter, reference to surgery should be taken to mean apicectomy and root-end filling.

Apicectomy and Root-End Filling

Rationale

As far as endodontic failures are concerned, an apicectomy is indicated:

-

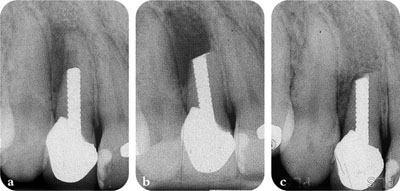

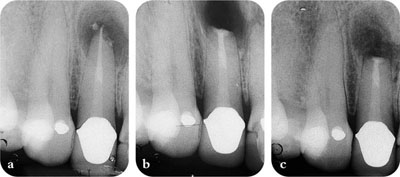

when conventional orthograde root canal treatment or non-surgical retreatment is impractical (Fig 8-1)

-

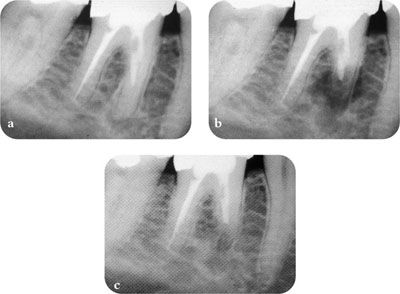

following the failure of conventional root canal treatment or non-surgical retreatment (Fig 8-2)

-

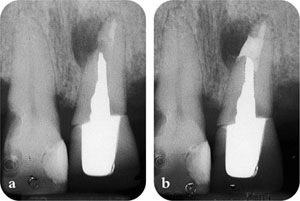

as an adjunct to non-surgical retreatment, e.g., to correct procedural errors (Fig 8-3)

-

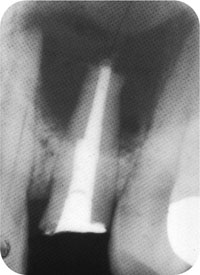

when biopsy or exploratory investigation is indicated, e.g., to manage a cyst or other suspect lesions (Fig 8-4).

Fig 8-1 Surgery indicated when non-surgical retreatment impracticable. (a) Tooth with large threaded post. (b) Apicectomy performed and MTA root-end filling placed. (b) One-year review.

Fig 8-2 Surgery following unsuccessful non-surgical retreatment. (a) Mesial canals not completely negotiable. (b) Mesial root apicected to level of orthograde root filling, no root-end filling necessary. (c) Six-month review.

Fig 8-3 Correction of procedural error. (a) Post space perforation. (b) Postsurgical repair.

Fig 8-4 Surgery indicated for biopsy and exploration of a large periapical lesion.

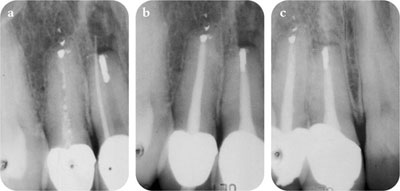

Apicectomy is primarily designed to remove the portion of root apex that is inaccessible to instrumentation and, as a consequence, cannot be cleaned, shaped or filled, or is associated with extraradicular infection (Fig 8-5), which is unresponsive to conventional orthograde treatment. During apicectomy, any overextended root filling and pathological tissues may be removed. A root-end filling is then placed to create a seal at the cut root end. The intention is to eliminate microorganisms in the untreated apical few millimetres, or imprison and seal them within the root canal system preventing their leakage. Deprived of sustenance and unable to cause any harmful effects, most microorganisms may eventually die. Unfortunately, it is now realised that such a premise is flawed because unless the root canal is properly cleaned, shaped and filled, even after apicectomy and placement of a root-end filling, viable microorganisms may still persist within the root canal system and cause apical periodontitis (Fig 8-6). Even if the root canal is not negotiable to the apex, a good-quality root filling should still be placed as far down as possible prior to surgery. This is considered crucial to a successful surgical outcome. Good surgical skill alone is insufficient to ensure success; correct case selection, thorough examination and an understanding of the biological basis of treatment are important. On the other hand, the presence of a complex coronal restoration or post can no longer be regarded as justification for the surgical approach, which is now rarely the recommended first line of management in endodontic failure. Readers may like to refer to Chapter 3 on the relative merits and limitations of surgery.

Fig 8-5 Surgical management of suspected extraradicular infection. (a) An overextended root filling and a periapical lesion. (b) Apicectomy, periapical curettage and root-end filling performed. Biopsy report confirmed extraradicular infection caused by actinomyces. (c) Review six months later.

Fig 8-6 Apicectomy and root-end filling will not eliminate the reservoir of infection within the root canal system. (a) Failure following surgery, a gutta percha cone in the sinus tract. (b) Following non-surgical retreatment. (c) Review one year later.

Medical and Dental Considerations

Medical and dental considerations are included as part of the preoperative assessment, as for any surgical procedure. The patient’s physician should be consulted if appropriate. The relevant radiographs should have been taken, possible complications clarified, prognosis explained and informed consent obtained.

General considerations for endodontic surgery are similar to those for tooth extraction.

Local considerations include the following:

-

access and visibility including sulcus depth

-

location and proximity of neurovascular bundles

-

anatomical structures including fraenal and muscle attachments

-

quality and quantity of periodontal support.

Preoperative Preparations

-

Patients should be advised to dress comfortably and, if necessary, an escort should be arranged to take them home afterwards.

-

Practise pre-emptive analgesia. Analgesics are more effective if taken prior to anticipated pain. So, if able to tolerate non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAID), the patient should take Ibuprofen 400 mg one hour before their appointment.

-

To reduce the risk of infection, the patient should be given an antiseptic mouthwash of chlorhexidine gluconate 0.2% (Corsodyl, GlaxoSmithKline, Brentford, Middlesex, UK) (Fig 8-7) to rinse for 1 min, before the commencement of surgery. Sometimes, the patient may be instructed to start the chlorhexidine mouthwash two days before surgery to reduce the oral flora and plaque formation.

Fig 8-7 Chlorhexidine antiseptic mouthwash.

Surgical Kit

A basic surgical kit should be assembled; individual practitioners will have preferences for particular instruments. An example of a surgical set-up containing instruments mentioned in this chapter is shown in Fig 8-8.

Fig 8-8 Example of surgical set-up. (a) Dappen dish and saline bowl. (b) Irrigating syringe and needle. (c) Local anaesthetic syringe, cartridge and needle. (d) Front surface mirror and DG16 endodontic explorer. (e) Briault probe. (f) Microsurgical blade and handle. (g) Mitchell’s trimmer. (h) Molt periosteal elevator. (i) Selection of surgical curettes. (j) Tissue forceps and locking tweezers. (k) Flat plastic. (l) Hollenback carver. (m) Root-end filling carrier. (n) Root-end filling plugger. (o) Micro-mirror. (p) Surgical haemostat. (q) Castroviejo needle holder. (r) Castroviejo scissors. (s) Suction tips. (t) Minnesota retractor. (u) Seldin retractor. (v) Silk suture. (w) Round and fissure surgical burs (Ash TC RA No. 8 round & No. 702 fissure burs). (x) Ultrasonic micro-tips. (y) Cotton pellets. (z) Ribbon gauze and square gauze.

Anaesthesia

Surgery is normally performed under local anaesthesia, but in the case of very anxious patients, conscious sedation may be arranged. General anaesthesia is seldom indicated and is preferably avoided since there is better control of the surgical field under local anaesthesia.

In general, the local anaesthesia required for apicectomy and root-end filling is the same as for tooth extraction. In the mandible, regional block anaesthesia must be administered and the tissues around the operation area also infiltrated with local anaesthetic solution. In the maxilla, buccal and palatal infiltration anaesthesia is required. In the anterior maxilla, the incisive papilla and canal will need to be anaesthetized as well. With infiltration anaesthesia, care should be exercised not to inject into the surrounding skeletal muscle or bleeding may be increased.

Local anaesthetic solutions of 2% lidocaine (lignocaine) with 1:80,000 adrenaline should provide effective anaesthesia and haemostasis. Formulations with 1:50,000 adrenaline (Fig 8-9), if available, are even more effective in controlling haemorrhage. A sufficient amount of local anaesthetic solution, typically 3–5 mL in a healthy individual, must be administered to ensure a bloodless field and profound anaesthesia during the whole procedure. Local anaesthetic solutions containing the synthetic polypeptide vasoconstrictor felypressin (octapressin) do not provide adequate haemostasis and should be avoided if possible.

Fig 8-9 Local anaesthetic solutions with (a) 1:100000; (b) 1:80000; or (c) 1:50000 adrenaline and (d) synthetic polypeptide vasoconstrictor felypressin (octapressin).

Flap Design and Reflection

Tissue flaps vary in designs, shapes and sizes. Whichever design is chosen should always fulfil the well-established surgical principles:

-

ensuring there is adequate blood supply to permit good healing

-

siting the edges of the flap to lie on sound bone to prevent breakdown of the flap margins (Fig 8-10); bony dehiscence and fenestration should be avoided

-

avoiding small flaps which will be bruised, stretched and torn in an effort to achieve good surgical access and unobstructed vision

-

remembering that flaps heal across the thickness of the wound, not the perimeter; larger, more adequate flaps are preferred

-

maintaining the integrity of interdental papillae and avoiding sharp angles

-

placing incisions accurately and cutting through periosteum

-

reflecting the flap cleanly and with minimum trauma to the tissues.

Fig 8-10 Mucosal defect exposing root end as a result of inappropriate flap design and soft tissue management.

An intrasulcular full-thickness mucoperiosteal tissue flap (Fig 8-11) provides excellent access and visibility, with minimal to no scarring and good healing. To facilitate better tissue approximation which enhances healing, the incision lines should be made with a single, firm cut with a scalpel. Micro-surgical scalpels (Swann-Morton Ltd., Sheffield, UK) (Fig 8-12) are available in different shapes, some double-edged. These smaller blades make it easier getting into the interproximal spaces and are also excellent for ensuring that the incisions follow the irregular contours of the underlying bone without slipping. The number of relieving incisions is dependent on the surgical access required. The relieving incisions should be made first, extending into the gingival crevice and including the gingival papilla. Relieving incisions should be vertical, not angled, as this will limit the number of vertically-running blood vessels severed, reducing the potential for haemorrhage. The horizontal incision is then made along the gingival crevice to join the vertical relieving incisions.

Fig 8-11 Outline of incision for an intrasulcular mucoperiosteal flap.

Fig 8-12 Microsurgical scalpel blades (bottom three) are smaller than conventional, normal size blades (top three).

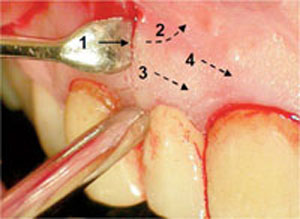

A Mitchell’s trimmer is used to reflect the tissue flap by lifting the periosteum from the bone at a vertical incision line (Fig 8-13). By slowly undermining the flap in a coronal direction, easing the periosteum off bone, the whole tissue flap is gently reflected. The flap should not be reflected from the gingival papilla or anywhere along the horizontal incision. Most periosteal elevators are too large and their use will crush, tear and damage the delicate gingival tissues, particularly the papillae. Once reflected, the flap should be protected with tissue retractors. For improved access and visibility, and to prevent excessive pulling of the tissue flap, surgery on anterior teeth may be performed with the patient’s mouth closed, biting on a piece of gauze.

Fig 8-13 Sequence of flap reflection. Begin at the middle of the vertical relieving incision (1), the flap is undermined (2) and elevated (3,4).

In cases in which crowns are present, a particular concern may be to preserve the aesthetics by avoiding flaps involving the marginal gingiva and interdental papilla. One such design, the submarginal rectangular flap, also referred to as the Luebke-Ochsenbein (Fig 8-14), consists of a scalloped, horizontal incision in the attached gingiva, following the marginal gingiva />

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses