Chapter 3

The Decision-Making Process

Aim

To review the factors influencing rational decision-making, when to treat and when not to treat failed endodontic cases.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter, the practitioner should be able to appreciate the many factors influencing decision-making, decide on the necessity, timing and preference for retreatment.

Introduction

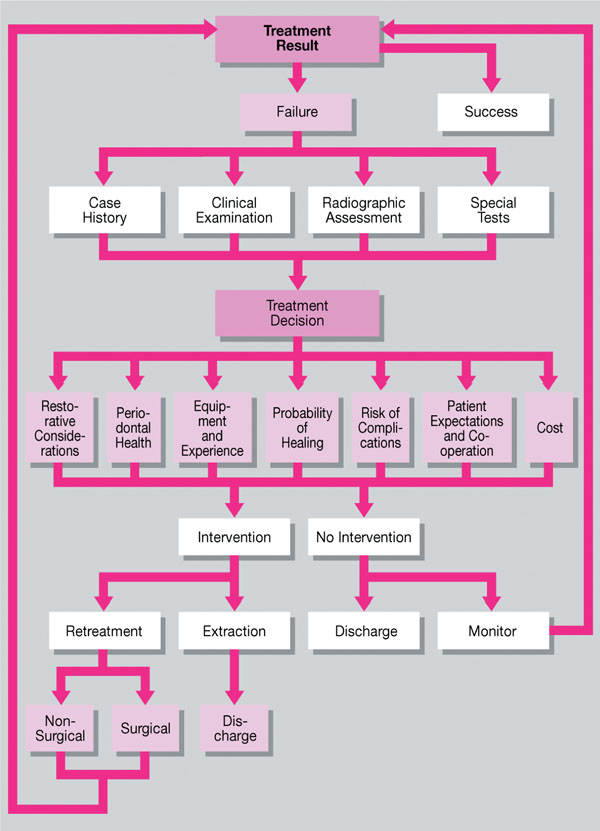

“Decisions, decisions, decisions”, from deciding that a case has failed, to deciding the cause of failure, and deciding if any and what action is needed, a major part of managing endodontic failures revolves around the decision-making process (Fig 3-1).

Fig 3-1 The complicated decision-making process when managing endodontic failure.

Decision-Making

Clinical decision-making is a complex task, often characterised as an informal intuitive process and regarded more as an art than a science. Arguments can often be made in both directions. Decision-making is about balancing risks: to intervene or watch and wait, to manage surgically or non-surgically. Finding the right balance is often imprecise but the intention should always be to avoid:

-

undertreatment – leaving infection untreated and the patient at risk of local or systemic morbidity

-

overtreatment – treating a healthy tooth unnecessarily or where, on balance, the patient has chosen to live with a chronic, symptom-free lesion for the time being.

The decision-making process starts when the patient and dentist first meet. Data collection centres on history taking, followed by a clinical examination and special tests. Armed with the necessary information, the clinician, relying on knowledge of the presentation of different diseases, makes a diagnosis. Then, a decision on treatment is made based on the:

-

clinician’s knowledge of the prognosis of the disease

-

effect of different treatment options

-

anticipated outcome

-

patient’s personal preference.

Other factors will also come into play, affecting rational decision-making, these include:

-

attitudes of both the clinician and patient

-

values: in particular, the cost/benefit to the patient

-

financial resources available, including the funding of alternative forms of treatment.

It is considered important to review the information feeding into the decision-making process.

Case Selection

Case History

Some patients are well informed, motivated and have a good recollection about any previous endodontic treatment. In contrast, others are poorly motivated and may not even realise that the tooth in question has been previously root treated. A comprehensive history of the previous treatment of the tooth, ideally in chronological order, is helpful and should cover the following questions:

WHAT endodontic treatment has previously been provided?

Endodontic therapy includes root canal treatment, pulp capping, pulpotomy and surgical endodontics. Sometimes a tooth may have had more than one of these procedures performed. Details of previous treatment will enable an assessment as to the feasibility of retreatment or whether the tooth has indeed come to the end of the road. Dental records, when available, should be consulted as patients may often not be fully informed about previous treatment.

WHY was the previous treatment required?

Information on the original complaint which led to endodontic treatment provides an indication of the pretreatment status of the pulp and periapex. The history of the management of the tooth will also help explain any presenting findings – for example, root resorption – and provide an indication of prognosis. In general, the success rate for the retreatment of teeth with a previously vital pulp is higher than in non-vital cases. Likewise, the success rate for the retreatment of teeth with obstructed root canals is dependent on the preoperative pulpal status and the presence or absence of a periapical radiolucency.

WHEN was treatment carried out?

Knowing how long ago the original treatment was carried out may provide clues about techniques or filling materials that may have been used. Materials and techniques which were once fashionable may now be considered obsolete.

By WHOM was the treatment carried out?

Standards of treatment can vary from one dentist to another. The level of expertise, time and financial constraints may have dictated the use of less than ideal techniques and materials; notwithstanding, all practitioners are expected to provide high standards of treatment.

WHERE was the treatment carried out?

Endodontic techniques practised and materials used vary from country to country and with different treatment philosophies. For example, paste-type root canal filling materials may still be popular in some countries. International air travel means patients are increasingly more mobile; they may have had treatment carried out in another continent. It is therefore relevant to know where treatment was performed and have an appreciation of international variations in endodontic treatment.

Clinical Examination

Extraoral examination

The patient’s face and neck are examined for signs of:

-

swelling (Fig 3-2a)

-

tenderness

-

asymmetry

-

sinus tracts (Fig 3-2b)

-

lymphadenopathy, specifically swelling or tenderness of the cervicofacial lymph nodes.

Fig 3-2 Clinical examination may reveal: (a) facial swelling; (b) remnant of an extra-oral sinus tract; (c) an intraoral buccal swelling.

The extent of the patient’s mouth opening should also be evaluated. Access and visibility often dictate the ease of performing retreatment. Limited access may be the reason why the original root treatment was less than satisfactory. Access for retreatment is generally considered inadequate if a patient’s mouth opening is less than two-fingers’ breadth but every case should be considered individually. It is difficult, for example, to access a molar tooth for non-surgical retreatment which is at the back of a very small mouth. By contrast, surgical retreatment of anterior teeth, even if access is limited, may be achievable with the patient’s mouth closed for most of the procedure.

Intraoral examination

The dental tissues surrounding the tooth and its neighbours are inspected visually and palpated to detect the presence of any:

-

swelling (Fig 3-2c)

-

sinus tract

-

tenderness.

If present, a sinus tract should be explored by inserting a gutta percha cone and taking a radiograph to track the source of the infection. It must not be assumed that a sinus tract in proximity to a tooth is evidence of that tooth being the culprit. Infections tend to track through tissues following the path of least resistance, so the source may be some distance from a sinus opening.

The tooth is also checked for:

-

quality and quantity of periodontal bony support

-

mobility

-

tenderness to pressure

-

cracks

-

colour, compared with adjacent teeth.

To determine if there is any tenderness or mobility, the tooth is percussed or assessed by means of finger pressure. Tooth mobility, if present, should be graded and recorded.

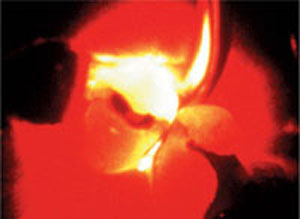

The presence of cracks may be determined by carrying out a “bite test”; this consists of biting on any object which produces a wedging effect and a painful response, which is relieved by releasing the bite. This test is, however, of limited reliability when teeth have already been root treated. In such cases, transillumination (Fig 3-3) may prove useful. If a crack is present, the light transmission will be altered, rendering the crack visible. Magnification, if available, may further help crack detection.

Fig 3-3 Crack detection by transillumination.

Radiographic Assessment

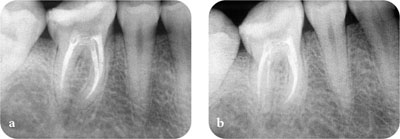

Good-quality radiographs are an essential part of the assessment of previously root treated teeth. Guidelines on quality assurance in dental radiology should be followed to optimise diagnostic information whilst limiting the radiation doses to as low a level as reasonably practicable. Radiographs should be taken by the paralleling technique using beam-aiming devices. Additional angled radiographs may be required to build a three-dimensional (3D) understanding of the case (Fig 3-4). As mentioned in Chapter 2, the quality of the radiographic images is dependent on proper handling, processing and viewing of the films.

Fig 3-4 What you see and what you don’t? (a) Radiograph showing an adequate root filling. (b) A second radiograph, taken at a different angle, revealed inadequacies and a second distal root.

Clear, undistorted radiographs with good contrast (Fig 3-5) will help determine the:

-

quality of the previous root filling and existing coronal restoration

-

type of root filling material present

-

occurrence of any procedural errors

-

possible cause of failure

-

likelihood of success in retreating a tooth.

Fig 3-5 Quality radiographs are essential; they reveal: (a) inadequate root fillings in both the first and second molars, caries under the crown in the second and third molars and possible furcal perforation in the second molar and (b) a complicated root canal morphology and two retained instruments in the first premolar.

It should also reveal the:

-

number of roots and canals present

-

root and canal shape and curvature

-

other relevant information on the previous root filling.

The quality of the coronal restoration, width of the periodontal ligament space, and the presence, location, size and nature of the margin of any radiolucencies or radiopacities should all be noted.

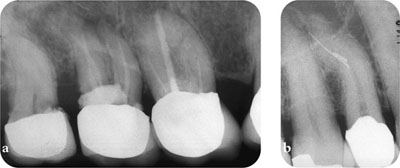

If available, previous radiographs should be used for comparison to determine whether a periapical lesion is enlarging, remaining the same size or healing slowly. If a lesion has remained the same size radiographically or remained relatively large despite some reduction in size, the previous treatment cannot be considered a success but neither is it a clear failure. In this situation, according to ESE guidelines (see Chapter 1), it is advisable to review the case until the lesion has resolved, or for a period of up to four years. After this time the root canal treatment may be considered a failure if total repair has not occurred (Fig 3-6). What remedial action is then taken will depend on the presence of any other signs and symptoms, and following detailed dialogue with the patient.

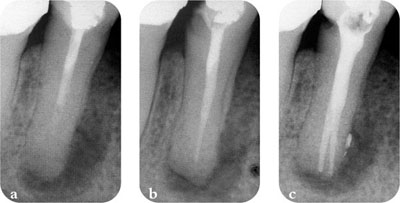

Fig 3-6 Failure according to ESE guidelines. (a) Original root filling. (b) Four years later, the periapical lesion diminished in size but not completely resolved. (c) Following non-surgical retreatment, there are actually two canals.

Restorative Considerations

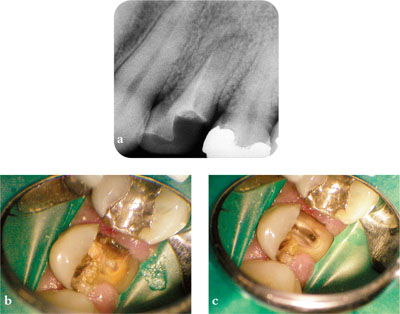

The state of the tooth and the condition of any existing restorations, including the presence of caries have bearings on selection for retreatment. Caries and defective restorations must be removed to assess the restorability of the tooth (Fig 3-7). There must be sufficient tooth structure to enable the provision of a satisfactory restoration after successful retreatment. Gross caries may determine that a tooth cannot be retreated, and is better extracted (Fig 3-8). If the tooth is not restorable, then it is pointless retreating the tooth.

Fig 3-7 It is vital to ascertain the restorability of a tooth before embarking on retreatment. (a) Pre-op radiograph. (b) Before and (c) after removal of gross caries.

Fig 3-8 Caries may mean a tooth is not restorable and retreatment is pointless.

The restoration must be replaced by an appropriate provisional restoration prior to root canal retreatment if it is:

-

deficient

-

undergoing significant marginal breakdown

-

associated with secondary or recurrent caries.

Regardless of whether a new coronal restoration is placed, it is imp/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses