Chapter 7

Managing Canal Obstructions

Aim

To describe techniques for managing canal obstructions including broken instruments, blockages and ledges.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter, the practitioner should be aware of techniques to tackle broken instruments, and to overcome blockages and ledges. Effective management of canal obstructions will help secure successful canal negotiation, debridement and retreatment.

Introduction

Sometimes the full length of the root canal system may be inaccessible owing to an obstruction. This may be due to:

-

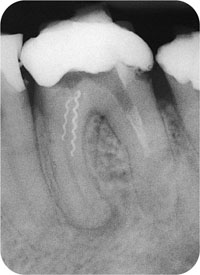

a retained instrument (Fig 7-1)

-

blockage of natural tooth substance or foreign material

-

a ledge created iatrogenically.

Fig 7-1 Fractured instruments obstructing mesial canals.

Obstructions may have hindered earlier efforts to achieve infection control and may be a primary factor in causing treatment failure.

General Guidelines

Prevention is better than cure, but canal obstructions can occur despite care and attention. Helpful guidelines to overcome canal obstructions include:

-

Acquiring good-quality, angled radiographs to help disclose root curvatures, the location of the blockage and whether the canal is patent below the obstruction.

-

Being aware that root canals may be more curved than anticipated. It is important to be aware that canals may have curvatures not only in a mesiodistal but also a buccolingual direction. Think three-dimensionally and try to visualise the root canal morphology.

-

Using magnification and additional lighting – being able to see clearly is invaluable when managing obstructions.

-

Removing all caries, unsupported tooth structure and restorative materials around the access cavity opening. Clear the pulp chamber of all materials and debris which may fall into the canals by flushing with copious amounts of irrigant; repeat as often as necessary. An ultrasonic scaler is particularly effective for this purpose.

-

Widening the coronal access by flaring the canal entrance to allow better visibility and access.

-

Improving the radicular access to the level of the obstruction by opening up the glide path as wide as possible for unimpeded straight-line access. This may be carried out using Gates-Glidden burs or NiTi coronal flaring rotary instruments.

Managing Retained Instruments

Ideally, all retained instruments should be removed. However, the management of a retained instrument is very much dependent on its:

-

location

-

configuration

-

material of manufacture.

For example, Hedstrom files are like woodscrews (Fig 7-2) and tend to be very retentive if broken and engaged in dentine. Spiral fillers may act like a spring (Fig 7-3); pulling at the coronal end will merely stretch but not dislodge the instrument. NiTi instruments, being more flexible than those made of stainless steel, are more liable to break off further when inappropriate removal is attempted.

Fig 7-2 Hedstrom files are like woodscrews (SEM).

Fig 7-3 Fractured spiral fillers obstructing mesial canals.

The consequences of leaving a retained instrument is critically dependent on the microbial status of the canal when the procedural accident occurred.

The microbial status is dependent on the:

-

pretreatment pulpal state

-

presence or absence of a periapical radiolucency.

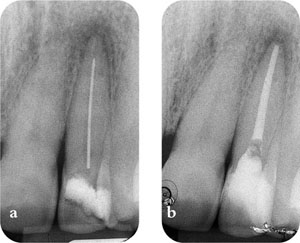

In general, if instrument separation occurs during the treatment of a vital pulp, provided the root canal system is not opened to microbial ingress, the long-term prognosis remains good. On the other hand, in cases of established apical periodontitis, retrieval of a broken instrument is highly desirable, if not essential, for a predictable biological outcome (Fig 7-4). Relying on the separated instrument to provide an effective apical seal is often fanciful and infection is likely to persist. Surgery may be the only option if an instrument is protruding beyond the apical foramen and not amenable to retrieval by non-surgical means (Fig 7-5). General guidelines for management of canals obstructed by foreign objects are set out in Table 7-1.

Fig 7-4 Fractured instrument in a tooth with apical periodontitis should be retrieved and retreated as it cannot provide a reliable and effective apical seal. (a) Pre-op radiograph. (b) Post-op radiograph.

Fig 7-5 Surgery may be the only option if fractured instruments are protruding into the periapex.

| Level of obstruction | Procedure |

| Coronal part of canal | |

| All cases | Retrieval followed by retreatment. |

| Middle third of canal | |

| Possible to retrieve | Retrieval followed by retreatment. |

| Impossible to retrieve, but can bypass | Bypass, retreatand incorporate into the root filling. |

| Impossible to bypass | Retreat to level of obstruction and review. Surgical retreatment may be indicated subsequently. |

| Apical third of canal | |

| Possible to retrieve | Retrieval followed by retreatment. |

| Impossible to retrieve, but can bypass | Bypass, retreatand incorporate into the root filling. |

| Impossible to bypass, tight seal by object | Retreat to level of obstruction and review. |

| Impossible to bypass, lack of effective seal | Retreat to level of obstruction and review, follow-up surgery if indicated. |

| Object protruding through apical foramen | Retreat to level of obstruction followed by surgery if then indicated. |

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses