Clinical Evaluation of the Implant Patient

Endosseous dental implants and their retained prostheses have had great success over the past few decades following the landmark research and development of osseointegrated implants by Brånemark et al.15–17 Initially, most prosthetic reconstructions with osseointegrated implants were limited to use in the edentulous patient, with many reports documenting excellent long-term success of implant-retained prostheses for edentulous patients.1,2,25

Following much success with implants in edentulous patients, the original implant treatment protocols were adapted for use in partially edentulous patients. Although some transitional problems were associated with the early use of dental implants in the partially edentulous patient, successes were achieved for this population as well. Subsequently, modifications in implant design, procedural techniques, and treatment planning greatly improved implant therapy for the partially edentulous patient. Currently, the long-term success of dental implants used to replace single and multiple missing teeth in the partially edentulous patient is very good29,40,42,48,52 (see Chapter 84). Additionally, with the implementation of bone augmentation procedures, even patients with inadequate bone volume have a good opportunity to be successfully restored with implant-retained prostheses.27,34,53 Virtually any patient with an edentulous space is a candidate for endosseous implants, and studies suggest that greater than 90% to 95% success rates can be expected in healthy patients with good bone and normal healing capacity.24

Case Types and Indications

Edentulous Patients

The original design for the edentulous arch was a fixed-bone–anchored bridge that used five to six implants in the anterior area of the mandible or the maxilla to support a fixed, hybrid prosthesis. The design is a denture-like complete arch of teeth attached to a substructure (metal framework), which in turn is attached to the implants with cylindrical titanium abutments (Figure 72-1). The prosthesis is fabricated without flange extensions and does not rely on any soft tissue support. It is entirely implant supported (see Figure 75-13). Usually, the prosthesis includes bilateral distal cantilevers, which extend to replace posterior teeth (back to premolars or first molars).

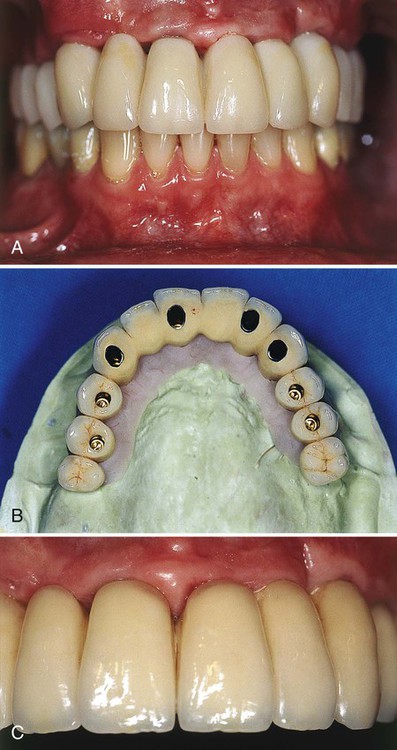

Another implant-supported design used to restore an edentulous arch is the ceramic-metal fixed bridge (Figure 72-2). Some patients prefer this design because the ceramic restoration emerges directly from the gingival tissues in a manner similar to the appearance of natural teeth. Depending on the volume of existing bone, the jaw relationship, the amount of lip support, and phonetics, some patients may not be able to be rehabilitated with an implant-supported fixed prosthesis.

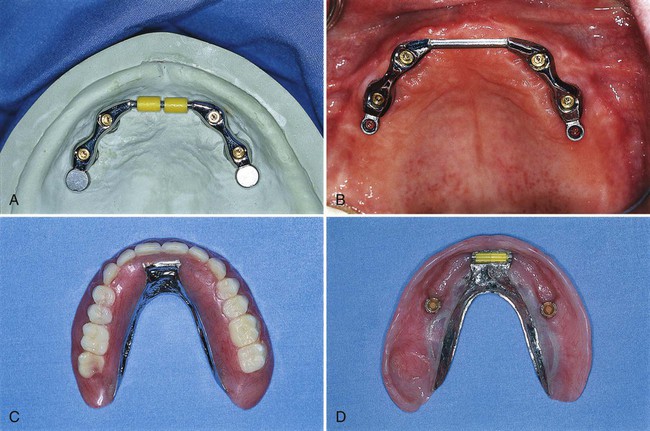

Depending on the volume of existing bone, the jaw relationship, the amount of lip support, and phonetics, some patients may not be able to be rehabilitated with an implant-supported fixed prosthesis. For these patients, a removable, complete-denture type of prosthesis is a better choice because it provides a flange extension that can be adjusted and contoured to support the lip, and there are no spaces for unwanted air escape during speech. This type of prosthesis can be retained and stabilized by two or more implants placed in the anterior region of the maxilla or mandible. Methods used to secure the denture to the implants vary from separate attachments on each individual implant to clips or other attachments that connect to a bar, which splints the implants together (Figure 72-3). Advantages and disadvantages of these attachment designs are discussed in Chapter 76.

Although the stability of the implant-retained overdenture does not compare to the rigidly attached, implant-supported fixed prosthesis, the increased retention and stability over conventional complete dentures is an important advantage for denture wearers.55 Additionally, implant-assisted and implant-supported prostheses are thought to protect alveolar bone from additional bone loss caused by long-term use of removable prostheses that are bearing directly on the alveolar ridges.

Partially Edentulous Patients

Multiple Teeth.

Partially edentulous patients with multiple missing teeth represent another viable treatment population for osseointegrated implants, but the remaining natural dentition (occlusal schemes, periodontal health status, spatial relationships, and esthetics) introduces additional challenges for successful rehabilitation.41 The juxtaposition of implants with natural teeth in the partially edentulous patient presents the clinician with challenges not encountered with implants in the edentulous patient. As a result of distinct differences in the biology and function of implants compared with natural teeth, clinicians must educate themselves and use a prescribed approach to the evaluation and treatment planning of implants for partially edentulous patients (see Chapter 74). In general, endosseous dental implants can support a freestanding fixed partial denture. Adjacent natural teeth are not necessary for support, but their close proximity requires special attention and planning.11 The major advantage of implant-supported restorations in partially edentulous patients is that they replace missing teeth without invasion or alteration of adjacent teeth. Preparation of natural teeth becomes unnecessary, and larger edentulous spans can be restored with implant-supported fixed bridges.49 Moreover, patients who previously did not have a fixed option, such as those with Kennedy Class I and II partially edentulous situations, can be restored with an implant-supported fixed restoration (Figure 72-4).

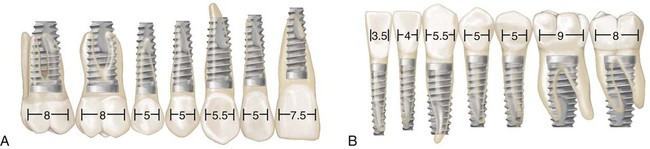

Early attempts to use endosseous implants to replace missing teeth in the partially edentulous patient were a challenge partly because the implants and armamentarium were designed for the edentulous patient and did not have much flexibility for adaptation and use in the partially edentulous patient. Today, clinicians have many choices in terms of implant length, diameter, and abutment connection to choose for the optimal replacement of any missing tooth, large or small (Figure 72-5).

The primary challenge with partially edentulous cases is an underestimation of the importance of treatment planning for implant-retained restorations with an adequate number of implants to withstand occlusal loads. For example, one problem that required correction was the misconception that two implants could be used to support a long-span, multiunit fixed bridge in the posterior area. Multiunit fixed restorations in the posterior jaw are more likely to experience complications or failures (mechanical or biologic) when they are inadequately supported either in terms of the number of implants, quality of bone, or strength of the implant material (see Chapter 74). The use of implants of adequate width and length and better treatment planning (more implants used to support more restorative units), particularly in areas of poor-quality bone, has solved many of these problems.

Single Tooth.

Patients with a missing single tooth (anterior or posterior) represent another type of patient who benefits greatly from the success and predictability of endosseous dental implants (see Video 72-1: Single Esthetic Implant Slide Show ![]() ). Replacement of a single missing tooth with an implant-supported crown is a much more conservative approach than preparing two adjacent teeth for the fabrication of a tooth-supported fixed partial denture. It is no longer necessary to “cut” healthy or minimally restored adjacent teeth to replace a missing tooth with a nonremovable prosthetic replacement (Figure 72-6). Reported success rates for single-tooth implants are excellent.23

). Replacement of a single missing tooth with an implant-supported crown is a much more conservative approach than preparing two adjacent teeth for the fabrication of a tooth-supported fixed partial denture. It is no longer necessary to “cut” healthy or minimally restored adjacent teeth to replace a missing tooth with a nonremovable prosthetic replacement (Figure 72-6). Reported success rates for single-tooth implants are excellent.23

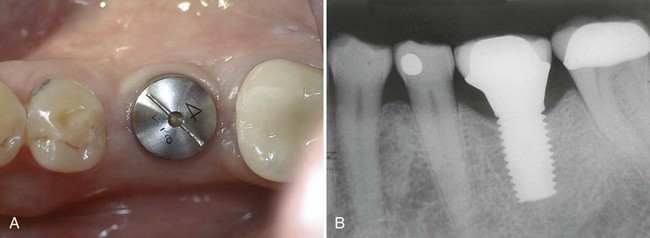

Replacement of an individual missing posterior tooth with an implant-supported restoration has been successful as well. The greatest challenges to overcome with the single-tooth implant restorations were screw loosening and implant or component fracture. Because of increased potential to generate forces in the posterior area, the implants, components, and screws often failed. Both these problems have been addressed with the use of wider-diameter implants and internal fixation of components (Figure 72-7). Wide-diameter implants often have a wider platform (restorative interface) that resists tipping forces and thus reduces screw loosening. The wide-diameter implant also provides greater strength and resistance to fracture as a result of increased wall thickness (the thickness of the implant between the inner screw thread and the outer screw thread). Implants with an internal connection are inherently more resistant to screw loosening and thus have an added advantage for single-tooth applications.

Esthetic Considerations.

Anterior single-tooth implants present some of the same challenges as the single posterior tooth supported by an implant, but they also are an esthetic concern for patients. Some cases are more esthetically challenging than others because of the nature of each individual’s smile and display of teeth. The prominence and occlusal relationship of existing teeth, the thickness and health of periodontal tissues, and the patient’s own psychologic perception of esthetics all play a role in the esthetic challenge of the case. Cases with good bone volume, bone height, and tissue thickness can be predictable in terms of achieving satisfactory esthetic results (see Figure 72-6). However, achieving esthetic results for patients with less-than-ideal tissue qualities poses difficult challenges for the restorative and surgical team.12 Replacing a single tooth with an implant-supported crown in a patient with a high smile line, compromised or thin periodontium, inadequate hard or soft tissues, and high expectations is probably one of the most difficult challenges in implant dentistry and should not be attempted by novice clinicians.

Pretreatment Evaluation

Medical History

A thorough physical examination is warranted if any questions arise about the health status of the patient.15 Appropriate laboratory tests (e.g., coagulation tests for a patient receiving anticoagulant therapy) should be requested to evaluate further any conditions that may affect the patient’s ability to undergo the planned surgical and restorative procedures safely and effectively. If any questions remain about the patient’s health status, a medical clearance for surgery should be obtained from the patient’s treating physician.

Intraoral Examination

After a thorough intraoral examination, the clinician can evaluate potential implant sites. All sites should be clinically evaluated to measure the available space in the bone for the placement of implants and in the dental space for prosthetic tooth replacement (Box 72-1). The mesial-distal and buccal-lingual dimensions of edentulous spaces can be approximated with a periodontal probe or other measuring instrument. The orientation or tilt of adjacent teeth and their roots should be noted as well. There may be enough space in the coronal area for the restoration but not enough space in the apical region for the implant if roots are directed into the area of interest (Figure 72-8). Conversely, there may be adequate space between roots, but the coronal aspects of the teeth may be too close for emergence and restoration of the implant. If either of these conditions is discovered, orthodontic tooth movement may be indicated. Ultimately, edentulous areas need to be precisely measured using diagnostic study models and imaging techniques to determine whether space is available and whether adequate bone volume exists to replace missing teeth with implants and implant restorations. Figure 72-9 diagr/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses