Chapter 7

The Initial Consultation – Screening Examination

Aim

This chapter aims to provide the practitioner with a simple algorithm for assessing and screening all patients for periodontal diseases.

Outcome

At the end of this chapter the reader should understand the importance of an accurate and comprehensive history to making a periodontal diagnosis. They should be able to screen all patients rapidly to identify those at risk of periodontal disease in the future, but should also appreciate the limitations of the screening systems recommended.

The History

When a patient first attends for consultation it is important that a thorough history and examination take place and that at subsequent visits these are competently updated. Certain historical information is essential if the clinician is to reach a correct diagnosis and develop an appropriate treatment plan. It can be subdivided as follows.

The History of the Complaint

Information gleaned from a complaint history is often extremely useful. The main points to cover are:

-

The length of time the patient has been aware of the problem.

-

Determination of whether the problem is purely localized or whether there is systemic involvement.

-

A detailed description of the symptoms, including nature, frequency, severity, duration, etc.

-

Whether the nature of the symptoms has changed with time, e.g. changes in number, frequency or severity.

-

Whether anything exacerbates or relieves the symptoms.

-

Whether the patient has received treatment for the condition and, if so, when and from whom and whether this therapy was efficacious.

-

Whether there is a family history of the problem.

The Medical History

The key questions to be asked are given in detail elsewhere and need not be repeated here. There are, however, three main reasons for collecting this information:

-

It may, in whole or in part, explain why a particular condition is seen and may account for the severity of reported/observed symptoms/signs.

-

It should alert the clinician to the existence of systemic factors for which special precautions will be required to safeguard the patient during treatment, e.g. antibiotic prophylaxis.

-

It should alert the clinician to any disease processes suffered by a patient which may present a risk both to staff in the clinical setting and to subsequent patients, e.g. Hepatitis B carrier or patient with CJD.

The Social History

Details of what should be covered are available elsewhere. A social history should include a full history of habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption. It is a concern that increased numbers of young women in particular are smoking. It is important to consider tobacco smoking carefully because:

-

Tobacco smoking causes many potentially damaging changes in the body:

-

During smoking, nicotine is rapidly absorbed into the blood stream where 30% remains in free form. It is highly lipid-soluble and thus gains easy passage across cell membranes, where it appears particularly to affect neural tissue including the brain. This may help account for the psychological dependence effects.

-

Nicotine increases heart rate, cardiac output and blood pressure. It also acts directly upon blood vessels inducing vasoconstriction.

-

-

Tobacco smoking also causes potentially damaging oral changes:

-

Prolonged thermal and chemical irritation of oral mucosa from smoke may result in changes in the oral mucosa ranging from relatively benign conditions such as “smoker’s keratosis” and “nicotinus stomatitis” and more potentially sinister conditions such as leukoplakia through to frank carcinoma. The principal carcinogens within tobacco smoke include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and N-nitroso compounds.

-

Tobacco smoke is selectively bactericidal and causes changes in the oral microflora, resulting in a predisposition to candidosis.

-

Extrinsic staining of the teeth and soft tissues occurs due to deposition of tar products. Staining of the teeth encourages plaque accumulation due to the rough surface of the stain, which may, in “risk patients”, result in increased periodontal disease experience.

-

Smoking is heavily implicated in the aetiology of NUG.

-

Smokers produce more calculus than non-smokers. It is thought that irritation from the smoke results in an increased salivary flow rate. When saliva flow from the parotid gland, in particular, increases, the saliva produced has a higher pH and a raised concentration of calcium, resulting in increased precipitation of calcium phosphate. Calculus per se is relatively inert but it does have a rough surface which is plaque retentive, predisposing to periodontal problems in susceptible patients.

-

Epidemiological evidence suggests that smokers have higher plaque scores than non-smokers. This is not thought to be a direct effect of the smoking but is believed to be related to poorer plaque control.

-

There is increasing evidence demonstrating that the incidence, prevalence and severity of periodontal disease seen in smokers is greater than in non-smokers (see Chapter 4).

-

Vasoconstriction within the gingivae resulting from nicotine inhalation masks the important sign of BOP from the base of the pocket. Smokers must thus be examined carefully, otherwise the activity of periodontal disease may be underestimated.

-

Vasoconstriction also results in reduced GCF flow. As discussed in Chapter 3, this contains many host-defence products, whose reduction is potentially damaging.

-

It has been demonstrated that PMNLs derived from the gingival crevice in smokers show reduced chemotaxis, phagocytosis and migration rate (see Chapter 3). Reduced immune-inflammatory cell function is associated with aggressive forms of periodontitis.

-

Smoking reduces the success of both surgical and non-surgical periodontal therapy. Nicotine is adsorbed onto the root surface in smokers and can result in fibroblast disorientation.

-

-

The dental team can play an important role in smoking cessation counselling and in helping patients who wish to reduce or stop smoking to achieve this. A great deal of information is available about how correctly to approach smoking cessation, but it is essential that patients know that quitting smoking will produce an oral health gain.

The question of whether certain forms of dental/periodontal therapy should be denied to smokers on the grounds that the likelihood of success is reduced is an emotive issue. Implant placement and guided tissue regeneration are often not offered to smokers, while conventional periodontal surgery may be. When a treatment is technically demanding and time-consuming for the clinician and costly for the patient, both may wish to maximise the chance of a successful outcome.

Alcohol consumption is also important from a periodontal standpoint owing to the effects of chronic alcoholism on liver function and hence blood clotting.

The Examination

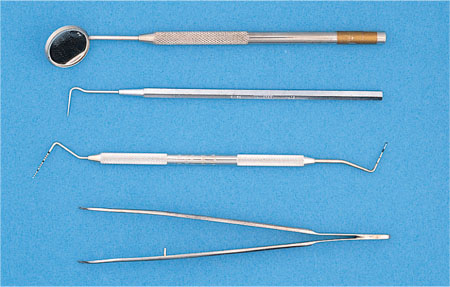

The examination begins extra-orally and normally includes examination and, as required, testing of the function of the temporomandibular joints (TMJ), the orofacial musculature and regional lymph nodes. This is followed by a general intra-oral examination designed to look at the soft and hard tissues within the mouth as a whole. An examination kit designed to achieve this is shown in Fig 7-1, though each clinician will have their own preferred instruments.

Fig 7-1 Photograph illustrating the basic instruments required to perform a clinical examination.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses