CHAPTER 7

Pigmentation (including bleeding)

• Amalgam tattoo (focal agyrosis)

• Melanocytic nevus (pigmented nevus)

• Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Rendu–Osler–Weber disease)

General approach

• Pigmentation of the oral mucosa may be due to melanin, blood, or foreign material.

• Pigmentation is rarely painful.

• Pigmented lesions may be either solitary or multiple.

• Pigmentation may represent neoplasia and therefore biopsy should be undertaken if there is any suspicion of malignancy or there is uncertainty of diagnosis.

Pigmentary changes can be divided on the basis of the extent of their involvement, either localized or widespread (Table 7).

Table 7 Patterns of pigmentation and differential diagnosis

Single or localized area of pigmentation

• Amalgam tattoo

• Hemangioma

• Melanocytic nevus (pigmented nevus)

• Melanotic macule (freckle)

• Malignant melanoma

• Kaposi’s sarcoma

Multiple or widespread areas of pigmentation

• Sturge–Weber syndrome

• Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

• Physiological pigmentation

• Addison’s disease

• Betel nut/pan chewing

• Peutz–Jegher’s syndrome

• Black hairy tongue

• Drug-induced pigmentation

• Smoker-associated melanosis

• Thrombocytopenia

Amalgam tattoo (focal agyrosis)

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Amalgam tattoo is an iatrogenic lesion caused by the traumatic implantation of amalgam particles into the soft tissues. Such a tattoo may occur during a tooth extraction, placement of an amalgam restoration, or amalgam polishing.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Amalgam tattoo is the most frequent cause of intraoral pigmentation and is seen on the gingivae (325), palate, buccal mucosa (326–328), and tongue. The tattoo appears as a slate-grey/black macule that does not change in appearance with time.

DIAGNOSIS

If there is any doubt about the clinical diagnosis, biopsy is indicated. Histological examination will show black particulate foreign material in the connective tissue that stains collagen fibers. If the amalgam particles are sufficiently large, they can be detected on an intraoral radiograph.

MANAGEMENT

No treatment is required apart from establishing the diagnosis.

325 Amalgam tattoo on the gingiva

326 Amalgam tattoo on the buccal mucosa.

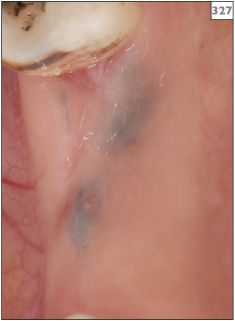

327 Amalgam tattoos in the upper right second molar edentulous ridge.

328 Amalgam tattoo in the lower left premolar region.

Hemangioma (vascular nevus)

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Hemangioma (or vascular nevus) is a congenital malformation of blood vessels. The term is more often and correctly applied to the cutaneous vascular lesions of the skin that appear in infants but subsequently regress during childhood. Most oral vascular malformations are not congenital since they develop in adulthood and do not regress. However, an oral hemangioma is identical both clinically and histologically to cutaneous hemangioma. Although not strictly correct, the term ‘hemangioma’ is also applied to these oral lesions. A more accurate term is probably ‘vascular anomaly’ or ‘vascular malformation’. Hemangioma may be divided into two forms depending on the type and size of the blood vessels involved. A capillary hemangioma consists of a mass of small, fine capillary vessels, whereas a cavernous hemangioma contains large, thin-wall vascular spaces.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Hemangioma may occur at any intraoral site, although the tongue, lips, and buccal mucosa are most frequently affected. Hemangiomas appear as well-circumscribed, flat or raised lesions with a blue discoloration (329–334).

330 Hemangioma presenting as a pigmented swelling within the tongue.

331 Hemangioma in the right buccal mucosa.

332 Hemangioma on the upper lip.

DIAGNOSIS

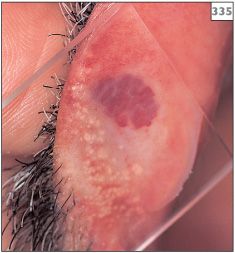

Blanching of the lesion when pressure is applied to it using a glass slide (diascopy) can help confirm the the presence of a cavernous hemangioma (335, 336). Since the blood vessels of a capillary hemangioma are small, this test is not so useful for diagnosing this lesion.

MANAGEMENT

The majority of cases of hemangioma do not require active treatment. However, prominent or nodular regions can become progressively traumatized and give rise to hemorrhage. If symptoms persist, small, localized lesions can be surgically excised or treated with cryotherapy. More extensive or deep lesions require specialist management incluing surgery and the possible use of sclerosing agents or embolization.

335, 336 Blanching of hemangioma following application of pressure under a glass slide.

Sturge–Weber syndrome

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

This congenital condition, also known as encephalotrigeminal angiomatosis, involves an angiomatous defect associated with the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve.

CLINICAL FEATURES

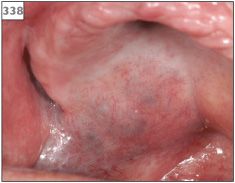

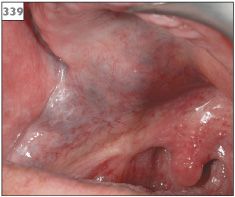

The striking visible feature is the ‘port wine stain’ appearance of the skin of the face, which is present from birth. The capillary defect is characteristically unilateral and limited to the distribution of one branch of the trigeminal nerve (337, 338). Other features include an ipsilateral leptomeningeal vascular anomaly, contralateral hemiplegia, and epilepsy. Intraorally, the gingivae and soft tissues in the affected region may appear blue in color and swollen (339).

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is made on the clinical appearance. Plain radiographs, MRI, or CT may reveal intracranial calcifications and the extent of the angiomas.

MANAGEMENT

Some patients benefit from cosmetic advice to cover facial lesions. Any dental treatment involving the extraction of teeth should be done in a hospital setting because of the risk of prolonged bleeding.

337 Characteristic facial appearance of Sturge–Weber syndrome in the maxillary division of the left trigeminal nerve.

338 Intraoral pigmentation in the palate due to the presence of a underlying vascular lesion.

339 Blue discoloration and swelling in the palate due to vascular abnormality of Sturge–Weber syndrome.

Melanocytic nevus (pigmented nevus)

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The term nevus, in a generic sense, means any congenital malformation. Unqualified or used in reference to melanocytes, the term refers to a benign neoplasm of melanocytes that is acquired or congenital. Melanocytic nevi can be junctional, compound, or intramucosal. Junctional nevi contain melanocytes located entirely within the epithelium, compound nevi contain melanocytes in the epithelium and in the superficial connective tissues, and intramucosal nevi contain melanocytes only in the connective tissues. A fourth type of nevus, termed ‘blue nevus’, is composed of pigmented spindle cells located in the connective tissues. Junc/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses