Chapter 7

Neurovascular Orofacial Pain

Aim

The aim of this chapter is to provide an insight into those neurovascular conditions that may present in the dental setting.

Outcome

Having read this chapter, the practitioner should be able to diagnose common headache disorders that may present dentally, together with gaining insight into differentiating neurovascular pain conditions from other orofacial pain disorders.

Case Presentation

-

Complaint. A 26-year-old policewoman presented to a busy general dental practice complaining of severe pain emanating from her upper left second premolar tooth. She described her pain as a throbbing sensation, grading it as an 8 on a 1–10 visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain. She suffered nausea when the pain was intense. On examination of the maxillary left molar and premolar teeth, the practitioner could not identify the source of the pain. In fact, the premolar teeth were unrestored and there was a small occlusal restoration only in the first molar tooth. The second molar tooth was unrestored and the third molar had been extracted six years previous. Further assessment, including a radiographical examination, failed to reveal any abnormalities, let alone the cause of the pain.

-

Clinical examination. On reading through the patient’s dental records, the practitioner noted that there were several entries of a similar nature spanning a period of nine months. On each occasion, the patient had been examined by a different dentist at the practice, with her current complaint being identical to her previous complaints. The pain recurred about once a month. It lasted two to three days before subsiding. It always started in the upper left second premolar tooth before evolving into a generalised headache. It was unilateral, always associated with nausea and best relieved by bed rest.

-

Treatment. The patient was eventually prescribed zolmatriptan (Zomig) an antimigraine medication. This controlled the pain from the time of onset. The patient had no further difficulties, subject to taking zolmatriptan whenever she sensed the toothache-type pain begin to develop.

Introduction

Although headache disorders fall into the neurological domain, many can present in the orofacial region. It is, therefore, important that the general dental practitioner is capable of differentiating neurovascular orofacial pain (OFP) from other OFP conditions. Common headache conditions include

-

tension type (muscular contraction headaches)

-

migraines

-

cluster headaches

-

giant cell arteritis (temporal arthritis).

There are other less common headache disorders that may also mimic tooth and jaw ache, but these are outside the scope of this book.

Many studies have demonstrated a close relationship between temporomandibular disorder (TMD) and headache. It is, therefore, not surprising that headache is one of the most common symptoms in patients with TMD. Furthermore, when treating patients with TMD complaints, many will report a marked reduction in their headache status. Patients with OFP may be found to have a higher prevalence of headache with greater disability impact than control subjects. The degree of disability tends to be strongly related to the musculoskeletal subcategories of OFP.

The International Headache Society has published an extensive classification of headache and facial pain disorders. These are broadly divided into three main categories, as outlined in Box 7-1.

Box 7-1 International Headache Society classification of headache disorders

Primary headaches

migraine

tension-type headache

cluster headache and other trigeminal autonomic cephalgias

others

Secondary headaches, associated with

head and/or neck trauma

cranial or cervical vascular disorder

non-vascular intracranial disorder

substance use or its withdrawal

infection

disorders of homeostasis

disorder of the cranium, neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cranial structures

psychiatric disorder

Other headaches

cranial neuralgias and central causes

other headache, cranial neuralgia, central or primary facial pain

From International Headache Society, 2003

The final headache category (other headaches) includes cranial neuralgias, and a wide variety of central and primary facial pain and headache disorders. The conditions include trigeminal neuralgia, post-herpetic neuralgia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. More importantly from a dental perspective, this category of headache also includes burning mouth syndrome and “persistent idiopathic facial pain”. This was formerly called “atypical facial pain”, a term that is now defunct.

Migraine

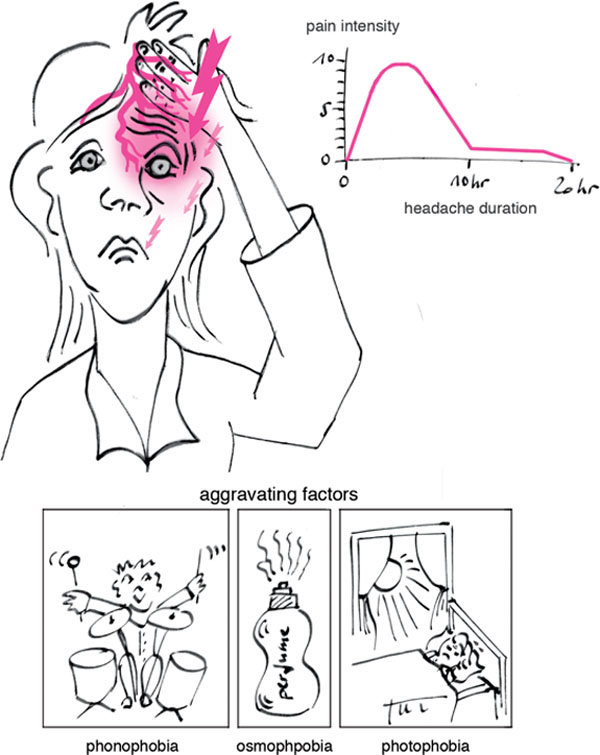

Migraine is a relatively common neurological disorder (Fig 7-1), the precise aetiology and mechanism of which continues to be the subject of extensive investigation. It has a female prevalence of 18% and a male prevalence of 6%. The typical migraine is unilateral, but it can be bilateral. It is associated with light sensitivity (photophobia), sound sensitivity (phonophobia), nausea and vomiting. Many patients seek a quiet dark room. Sleep may break the migraine attack. The pain is pounding and throbbing in quality. Very often it is located in the frontal, orbital, temporal and occipital regions. It is aggravated by physical exertion or simply movement of the head. It often lasts hours or possibly even days at a time. The headache associated with migraine can occur at any time of the day or night but is most common in the morning on waking. It has a gradual onset, peaks and then subsides. It is moderate to severe in intensity. Other symptoms of a migraine attack may include dizziness, frequent urination, diarrhoea, sweating and cold extremities. Migraine has a large genetic component. It is preceded by an aura in 15% of cases. Visual disturbances are the commonest form of aura. The disturbances may consist of coloured spots, flashing bright lights or shimmering multicoloured zigzag lines. Aura usually last 20–30 minutes, with the headache commonly following within 60 minutes of the end of the aura. Sensory and motor auras occur less commonly. There may be a strong hormonal association with migraines. Indeed, it is common for some women to have a predictable migraine attack at the time of their monthly menstrual cycle. Box 7-2 gives the International Headache Society classification of migraine headaches.

Fig 7-1 The patient with migraine.

Box 7-2 International Headache Society classification of migraine headaches

Description: recurrent headache disorder manifesting in attacks lasting 4–72 hours

Diagnostic criteria

At least five attacks fulfilling criteria B–D

B Attacks lasting 4–72 hours

C Headache has at least two of the following:

unilateral location

pulsating quality

moderate or severe in intensity

aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity

D During headache, at least one of the following:

nausea and/or vomiting

photophobia and phonophobia

E Not attributed to another disorder

From International Headache Society, 2003

The treatment options for migraine are extensive, including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. There are a variety of non-specific and specific migraine medications available. These are used at the time of the onset of a migraine attack to abort the subsequent headache and associated symptoms. Frequent migraine sufferers may opt for prophylactic medication, possibly taken on a daily basis. Non-pharmacological interventions are also many and varied, including lifestyle changes, stress management, relaxation techniques, biofeedback, homeopathy and acupuncture.

Tension-type Headache

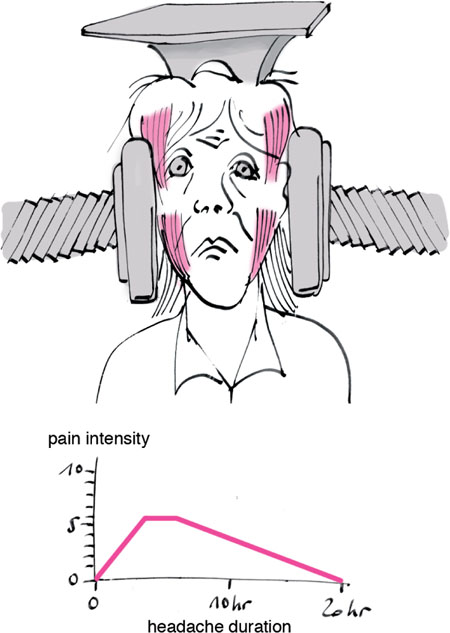

The tension-type headache (Fig 7-2) is by far the commonest form of headache. It affects 90% of the population at some time or other. Tension headaches differ in the clinical presentation from both migraine and cluster headaches in that they are mild to moderate in intensity, do not interfere with normal function and are not aggravated by physical exertion. They are usually bilateral and are often described as a tight band wrapped around the head. They have a squeezing, aching, pressure-like quality. They can share some of the symptoms associated with migraine, including photophobia and phonophobia.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses