Chapter 7

Neurological disorders

INTRODUCTION

Neurological disorders account for approximately 20% of admissions to general hospitals in the United Kingdom, an increasing proportion of which are emergencies (Sharief and Anand, 1997). Neurological disorders can be life threatening; altered consciousness level can lead to a compromised airway and compromised breathing. Neurological disorders in the dental practice require prompt effective treatment, together with close monitoring of ABCDE to detect deterioration.

The aim of this chapter is to understand the management of neurological disorders.

MANAGEMENT OF A GENERALISED TONIC–CLONIC SEIZURE

A seizure happens when there is a sudden burst of intense electrical activity in the brain (often referred to as epileptic activity), causing a temporary disruption to the way the brain normally works, resulting in an epileptic seizure (Epilepsy Action, 2013). In the United Kingdom, 600,000 people have epilepsy (Epilepsy Action, 2013). The incidence of epilepsy is estimated to be 50 per 100,000 per year and the prevalence of active epilepsy in the United Kingdom is estimated to be 5–10 cases per 1000 (NICE, 2012). Two-thirds of people with active epilepsy have their epilepsy controlled satisfactorily with anti-epileptic drugs (NICE, 2012).

There are over 40 different types of seizures; a person may have more than one type and recurrent seizures are defined as epilepsy (Epilepsy Action, 2013). In this section, the management of a patient having a generalised tonic–clonic seizure, sometimes called a grand mal fit, will be discussed. In the dental practice, these seizures account for approximately 7% of all medical emergencies encountered in the dental surgery (Müller et al., 2008).

Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy accounts for approximately 500 deaths each year (National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2002). Status epilepticus, a potentially life-threatening medical emergency, is associated with significant morbidity and mortality if not treated promptly (NICE, 2002). Injuries that can be sustained include fractures, burns, dislocations, concussion and intracerebral haemorrhage (American Heart Association, 2005). Dental injuries are quite common (Buck et al., 1997). Maintaining the patient’s safety during a seizure is a priority.

Signs and symptoms

Typical characteristics of a generalised tonic–clonic seizure (Jevon, 2006; Turner, 2007; Epilepsy Action, 2013; St John Ambulance et al., 2011) include:

- Sudden loss of consciousness (can be preceded by crying out) and collapse to the ground;

- Rigidity (tonic phase) – lasting for approximately 10 seconds, the body is stiff, the elbows are flexed and the legs are extended;

- Breathing stops; central cyanosis particularly noticeable around the mouth;

- Clenching of the jaw – saliva may accumulate at the mouth, which could be blood-stained if the casualty has bitten his tongue or lip;

- Convulsive movements (clonic phase) – lasting for 1–2 minutes, there is violent generalised rhythmical shaking;

- Incontinence;

- Variable period of unconsciousness following the event. The casualty may feel very tired and may fall into a deep sleep; he could be dazed, confused, disorientated, frightened and may have slurred, incomprehensible speech.

Causes

Causes of a generalised tonic–clonic seizure include:

- epilepsy (most common cause);

- head injury;

- certain poisons, e.g. alcohol, ecstasy;

- alcohol withdrawal;

- cerebral hypoxia;

- cerebral hypoglycaemia (Jevon, 2006).

Treatment

- If necessary, call 999 for an ambulance (see later in When to call 999 for an ambulance).

- Ensure that it is safe to approach the patient.

- Ask other patients to leave the room.

- Protect the patient from injury. Ensure the space around him is clear and remove any objects that are potentially dangerous objects.

- Loosen any clothing around the patient’s neck.

- Cushion the patient’s head, e.g. place something soft such as a pillow, jumper or jacket under his head. Alternatively, place the palms of your hands behind his head and support it to prevent injury.

- Administer oxygen 15 l/min.

- Note the time in order to check how long the seizure lasts.

- Consider measuring the patient’s blood glucose (fitting can be a presenting sign of hypoglycaemia), particularly if the patient is a child or a known diabetic (Resuscitation Council (UK), 2012). Treat hypoglycaemia if present (see pages).

- Check to see if the patient has a very slow pulse (<40 per minute) because this can lead to hypotension (low blood pressure) which can cause transient cerebral hypoxia leading to a brief seizure (Resuscitation Council (UK), 2012).

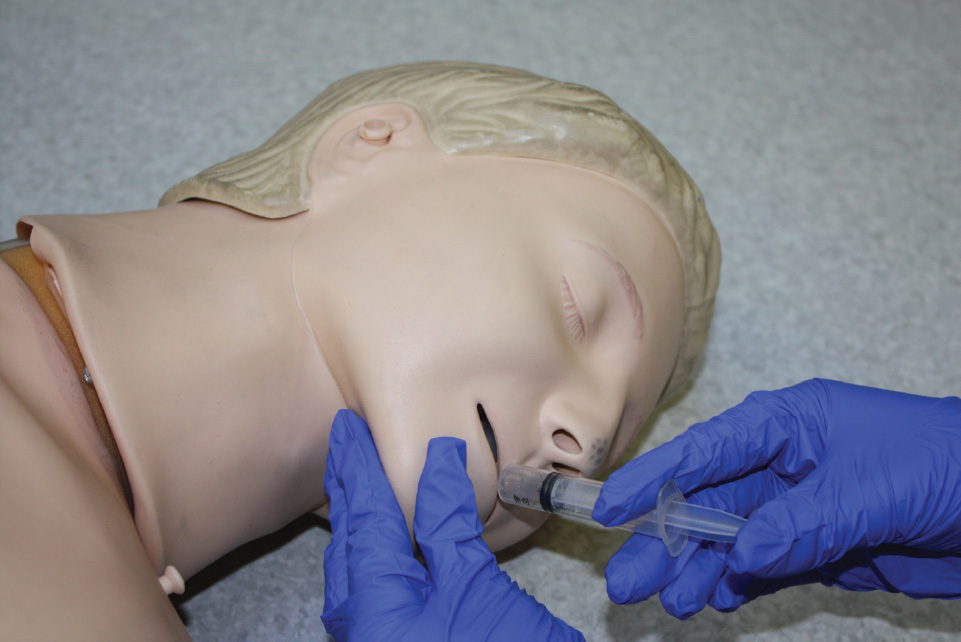

- Administer midazolam 10 mg via the buccal route (Figure 7.1) if seizures are prolonged (5 minutes or longer) or if the seizures are repeated rapidly (Resuscitation Council (UK), 2012; NICE, 2012) (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2013) (the doses of buccal midazolam in children are <5 years – 5 mg; 5–10 years – 7.5 mg; >10 years – 10 mg). There are currently three midazolam presentations listed in the latest BNF for buccal use (British Medical Association and Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 2013): midazolam injection (unlicensed), epistatus (unlicensed) and buccolam (paediatric licence; unlicensed in adults). In the dental practice, midazolam should be administered by (or under the supervision of) a dental practitioner (Resuscitation Council (UK), 2012).

- Once the seizure has stopped continue to monitor airway, breathing and circulation; if the patient is breathing normally, place him in the recovery position (if the patient is not breathing normally, start resuscitation – see Chapter 9).

- Wipe away any saliva; suction may be necessary.

- Check to see whether the patient has sustained any injuries.

- Calmly reassure the patient.

- Stay with the patient until he has made a complete recovery.

- Continue to administer oxygen to support breathing if necessary.

Source: St John Ambulance et al. (2011), Jevon and Morgan (2007), Epilepsy Action (2013), National Society for Epilepsy (2013)

Figure 7.1 Buccal administration of midazolam.

When to call 999 for an ambulance

Call 999 for an ambulance if:

- it is the patient’s first seizure; or

- the seizure continues for longer than 5 minutes; or

- one tonic–clonic seizure follows another without the casualty regaining consciousness between seizures (status epilepticus); or

- the patient incurs an injury during the seizure; or

- the patient requires urgent medical attention; or

- there is difficulty monitoring the patient; or

- there is a high risk of recurrence.

Source: NICE (2012), Resuscitation Council (UK) (2012)

Action not recommended during a seizure

During a seizure it is recommended not to:

- Restrain the patient;

- Insert anything in the patient’s mouth;

- Move the patient unless he is in danger;

- Give the patient anything to eat or drink until he has fully recovered;

- Attempt to arouse the patient.

Source: Epilepsy Action (2013)

Observations during a seizure

‘A clear history from the casualty and an eyewitness to the attack give the most important diagnostic information, and should be the mainstay of diagnosis’ (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2003). The following observations during a seizure will assist in its diagnosis and classification:

- Where was the patient and what was he doing prior to the seizure?

- Any mood change, e.g. excitement, anger or anxiety?

- Unusual sensations, e.g. odd smell or taste?

- Any prior warning?

- Loss of consciousness or confusion?

- Any colour change, e.g. pallor, cyanosis? If so where, e.g. face, lips, hand?

- Altered respiratory pattern, e.g. dyspnoea, noising respirations?

- Which part of the body affected by seizure?

- Incontinence?

- Tongue biting?

- Did the patient do anything unusual, e.g. mumble, wander about or fumble with his clothing?

- How long did the seizure last?

- How was the patient following the seizure? Did the patient need to sleep and, if so, for how long?

- How long before the patient can perform normal activities again?

Source: National Society for Epilepsy (2013)

Personalized care plane

A patient with epilepsy may have a personalised care plan drawn up by the local hospital which will probably include action in the event of a seizure. Although it would be prudent to follow this care plan should the patient have a seizure in the dental practice. However, it is still important to call 999 for an ambulance if it is indicated (see When to call 999 for an ambulance section in this chapter).

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses