7

Implant Complications: Peri-Implant Disease and Cement Residue Protocol

What is the hygienist’s role in restoratively driven implant complications?

Implants have proven to be an excellent treatment option for our patients. However, there is still some confusion that exists when it comes to the long-term assessment of these sophisticated medical devices. It is important to address this and to understand the role of the team members. The team members include the surgical dentist, restorative dentist, dental assistants, dental laboratory technician, dental hygienist, and the patient.

All members of the team should understand what to look for and how to detect potential complications. The dental hygienist will have the most important role in long-term maintenance and should be able to recognize what signs and symptoms to look for. He or she should also understand when surgical intervention is required. The other team members will depend on the dental hygienist for any information that may be pertinent to the long-term success of the implant.

The high survival rate of osseointegrated implants is well documented, but if an implant does fail it is generally due to bacterial infection, a poorly designed prosthesis, or over-extended occlusal force (occlusal overload) (1). Studies are now showing that only a small percentage of implant failures are due to occlusal overload (2), and the majority of the late failures of already integrated implants can be attributed to peri-implant infections and cement residue. Other signs of a failing implant are pain, mobility, and unacceptable bone loss.

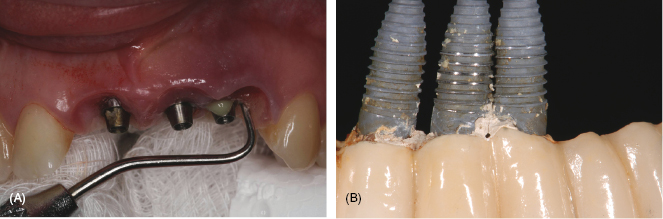

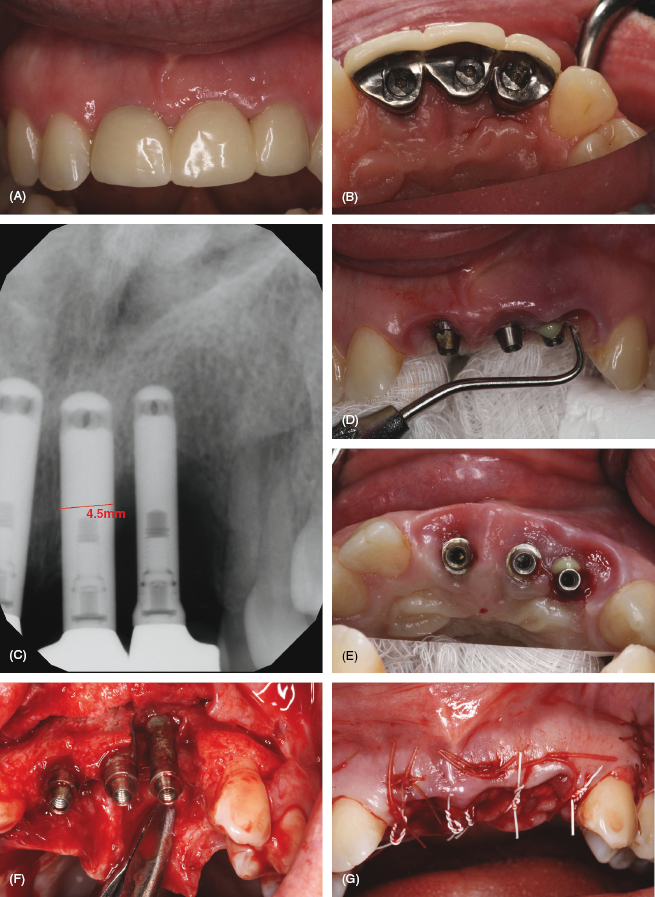

This chapter will focus on the complications of peri-implant disease (mucositis and implantitis) (refer to Figure 7.1A) and includes a special section by Alfonso Piñeyro on cement-induced peri-implant disease; see Figure 7.1B: what it is, how it develops, and the role of the dental hygienist in detection and diagnosis.

Figure 7.1 (A) Peri-implantitis. Courtesy of Dr. John Remien. (B) Cement residue. Courtesy of Dr. Alfonso Piñeyro.

Peri-implant disease

Research shows that the mucosal peri-implant tissues surrounding the exposed portion of a dental implant contain the same bacterial flora as the periodontium. Peri-implant tissues cascade from peri-mucositis to peri-implantitis in a similar progression of gingivitis to periodontitis around natural teeth (1) and are collectively known as peri-implant disease (i.e., mucositis and peri-implantitis) (2).

Peri-implant mucositis, similar in nature to gingivitis caused by bacteria, occurs in approximately 80% of patients who have implants placed in 50% of implant sites (3). It is manifested by redness and inflammation in the soft tissue around the implant, no bone loss, and is reversible. Improved oral hygiene and professional implant in-office maintenance prophylaxis by a hygienist can reverse mucositis to a healthy state.

Peri-implantitis, or bone loss around an implant, can be induced by stress, bacteria, or both. Stuart Froum states, “The diagnosis of peri-implantitis includes probe depths (PD) of 5 mm to 6 mm or greater, bleeding on probing, and bone loss greater than 2 mm to 3 mm around the implant. Treatment depends on the extent of PD and bone loss” (4).

Peri-implantitis is very similar to periodontitis, with significant inflammation and exudate. With peri-implantitis, a sulcular crevice deepens around the implant to allow bacteria to migrate down, causing bone loss that can be irreversible. On a radiograph, radiolucency in a “saucer” shape around the implant can occur in 28–56% of implants after 5 years at 12–40% of implant sites (3). Risk factors include poor oral hygiene, smoking, poorly fitting restorations, retained cement from cement-retained implant restorations, and poorly controlled diabetes (5).

Peri-implantitis is generally not painful and patients may not even be aware that they have an infection or that anything is wrong with their implant. Hygienists need to take note that there is also a 28.6% increase of peri-implantitis in patients that have had chronic periodontal disease compared with healthy patients at 5.8% (6, 7). This is an excellent reason to motivate patients to continue on regularly scheduled implant maintenance appointments. Monitor your periodontal disease patients closely who have chosen implant therapy and keep these patients on a more frequent implant maintenance schedule (7).

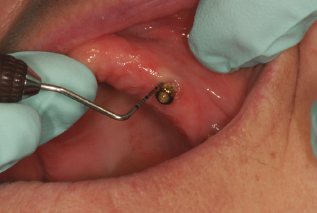

The diagnosis of peri-implantitis is based on probing depths of 5–6 mm or greater, bleeding on probing, and bone loss greater than 2–3 mm around the implant. Treatment depends on the extent of probe depth and the radiographic bone loss. That is why it is recommended that at every implant maintenance appointment the hygienist or dentist probe around an implant (4; see Figure 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Probing a Locator. Courtesy of Dr. Peter Fritz.

If the implant has a probing depth of 5–6 mm or greater, bleeding, and/or a presence of exudate, a radiograph(s) should be taken to assess the implant and evaluate for bone loss.

Record any signs of inflammation or bleeding upon probing surrounding a dental implant exposed to the oral environment. Also record any clinical symptoms of pain or mobility. Radiographs should also be taken if these symptoms are present to evaluate for bone loss; however, when a failing implant becomes mobile, it is considered a failure and may often need to be removed and replaced with a new implant when conditions warrant.

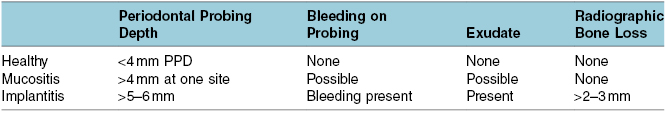

Check for pocket depth, inflammation, and bleeding, and/or palpate the ridge for signs of infection; see Table 7.1 and Table 7.2. Refer to Chapter 6 for more specifics on assessing, identifying, and monitoring for implants.

Table 7.1 Clinical signs of peri-Implant disease.

Table 7.2 Probe and palpate for signs of peri-implant disease.

| Probing for Signs of Infection | Palpating for Signs of Infection |

|---|---|

|

|

Protocol for peri-implant disease

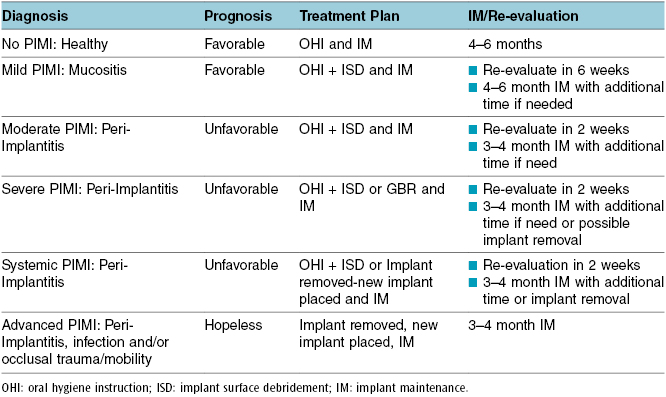

A protocol for determining prognosis and appropriate treatment for dental implants with peri-implant mucosal inflammation has been developed by Getulio Nogueira-Filho. A summarized version of this protocol is outlined in Table 7.3, which ranges from healthy with no peri-implant mucosal inflammation to advanced peri-implant mucosal inflammation (PIMI) (8).

Table 7.3 Summary PIMI system.

To further define this:

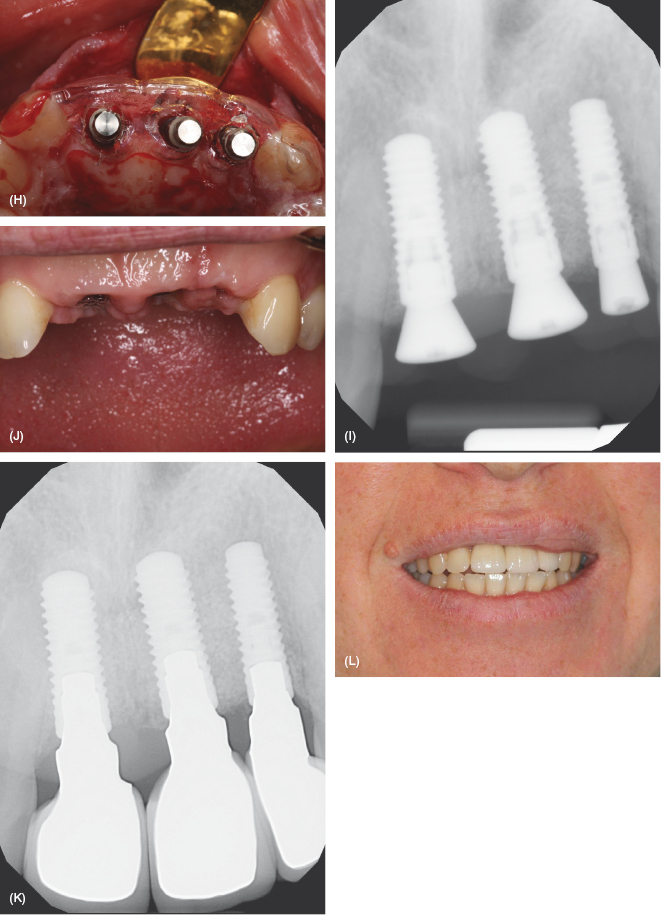

Figure 7.3 Peri-implantitis case. Courtesy of Dr. John Remien. (A) Peri-implantitis (facial view). (B) Peri-implantitis (lingual view). (C) Periapical X-ray. (D) Notice the exudate. (E) Occlusal view. (F) Full thickness flap elevation/removal of implants and granulomatous tissue. (G) GBR with xenograft (bovine), mineralized bone, and resorbable collagen membrane. (H) Implant placement after 6 months healing utilizing a surgical stent. (I) Periapical X-ray placed implants. (J) Tissue facial view pre-restorative. (K) Restored at 3 months post-implant placement. (L) Final photo. Courtesy of Dr. John Remien.

Treatment and maintenance for implants with peri-implant disease

Hygienists have an active role in mucositis and the nonsurgical phase of peri-implantitis. There is evidence to support nonsurgical therapy as a first step in the process of treatment for peri-implantitis. A study of two nonsurgical mechanical debridement procedures is recommended for treatment of peri-implantitis using titanium implant scalers and/or ultrasonic magnetostrictive implant insert (9). These procedures both achieve improvement of plaque and bleeding levels, but alone were not able to decrease the pocket depth. Added adjunctive procedures may be necessary to achieve a more long-lasting effect.

The combination of minocycline microspheres (e.g., Arestin) after titanium instrument debridement and ultrasonic lavage has shown improved treatment outcomes for a period of 12 months (10). Nonsurgical debridement with adjunct CHX and/or antibiotics can result in clinically relevant improvements of peri-implantitis. Studies of submucosal debridement alone may not be adequate for the removal of bacterial load from the surfaces of implants with peri-implant pockets >5 mm. Flap surgery with antimicrobial regimen or removal of the implant and replacement with new implant will be necessary (11, 12).

Protocol for peri-implant disease clinical treatment is outlined in Chapter 9. It identifies nonsurgical treatments with re-evaluation for implants with mucositis in 6 weeks and implantitis in 3 weeks. Hygienists are at the forefront for identifying and treating peri-implant disease as well as residue surrounding dental implants.

Cement residue complication

Contributed by Alfonso Piñeyro, DDS

Hygienists’ role in restoratively driven implant complications

This section will focus on cement-induced peri-implant disease: what it is, how it develops, and the role of the dental hygienist in detection and diagnosis. Refer to Figure 7.4.

Figure 7.4 Cement. Courtesy of Dr. Alfonso Piñeyro.

Restorative classification

In the majority of the cases, implant restorations are divided into two main restoration categories dictated by the manner of their attachment: screw-retained restorations and cement-retained restorations. Screw-retained crowns are attached to the implant fixture usually as a one- or two-unit structure (see Figure 7.5). The screw is tightened with the appropriate torque and the screw access hole is sealed off with the restorative material of the clinician’s choice. Cement-retained restorations are attached by means of a component known as an abutment. A crown is fabricated to be cemented over the abutment in a fashion similar to that of traditional tooth-retained crowns. Implant abutments are either stock abutments that are available from the manufacturers or custom abutments that are usually designed and fabricated for a more individualized fit.

Figure 7.5 (A) Example of a screw-retained implant crown. 1. Implant fixture: Integrated in bone and soft tissue adherence. 2. Anti-rotational portion: This will allow the crown to be secured to the implant. 3. Crown portion: 2 and 3 are part of the same unit; they are fixed together. 4. Implant crown screw: This screw will secure the crown (2 and 3) to the implant fixture. (B) Example of a cement-retained implant crown. 1. Implant fixture: Integrated in bone and soft tissue adherence. 2. Implant abutment: Notice the most apical portion has an anti-rotational feature. 3. Abutment screw: The screw will secure the implant abutment to the implant fixture. 4. Implant crown: The crown will be secured onto the implant with the use of dental cement. (C) Screw versus cement implant restorations. Panels A and B reprinted with permission from Dr. Boris Pulec. Courtesy of BioH/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses