7 Financing Dental Care

Health care historically has been provided on a fee-for-service basis, in which the patient pays the provider directly for services. This two-party system is a private contract involving only the provider and the patient. Methods of financing health care in the United States, however, have progressed far beyond this traditional system since the mid-1930s and especially since 1965. A fundamental change has been the emergence of third parties, meaning that the financing of health services is no longer a matter of a purely private contract between provider and patient. In 2001, for example, 86% of the total outlays for health services and supplies involved a third party, and 46% of all health care services were paid for by government funds.57 Dentistry’s entry into the third-party system has been more recent, but third-party involvement in the payment for dental care is now a major and still-evolving part of dental practice.

INSURANCE PRINCIPLES AND DENTAL CARE

To understand how dentistry fits into third-party payment, a review of insurance principles is helpful. During the years after World War II, when medical insurance was growing rapidly, dental care was one of the “fearful four” areas of health care (dental care, psychiatric care, prescription drugs, and long-term care) considered uninsurable by commercial insurers. This reasoning was based on the assumption that the nature of dental need violated the basic principles of insurance,22 which state that to be insurable a risk must be the following:

All health insurance violates some of these principles. For example, many of the benefits paid by health insurance represent relatively small amounts of money, and people with insurance are more likely to use care than those without it.37,42 Insurance carriers found they could get around these problems in several ways, such as the following:

Requiring patients to pay part of the cost of some services is an economic disincentive to overutilization. The portion of the cost of the service that a patient pays is either a deductible or coinsurance (sometimes called copayment). A deductible is a set amount of money that the patient must pay toward the cost of treatment before benefits of the program go into effect.4 A familiar example of a deductible is the “front-end” payment of a claim under automobile insurance. Coinsurance means that the patient pays a percentage of the total cost of treatment.4 For example, if a patient is to pay 20% of the cost of an amalgam restoration, the amount the patient must pay varies depending on the approved fee for an amalgam but in any case will be 20% of that fee.

After looking at the list of insurance principles, one can see why dental care was for a long time considered uninsurable. Nearly everyone has some dental treatment needs. They tend to be frequent rather than infrequent, and unlike the cost of hospital care the cost of dental treatment is rarely catastrophic. Nevertheless, evaluations of some of the earliest group prepayment plans indicated that dental care indeed was insurable because cost was found to be not the only barrier to dental care;49–51 even when the cost barrier was removed, potential patients did not pour in as many had expected. Although utilization of dental service was increased, it stayed well short of 100%. In other words, although all members of the group may have needed dental care and all were paying a premium toward it, only some members were seeking treatment. Indeed, if 100% of the group seeks dental care on a regular basis, it might be less expensive for them to pay for their care individually rather than through prepayment.

EXPENDITURES FOR HEALTH CARE

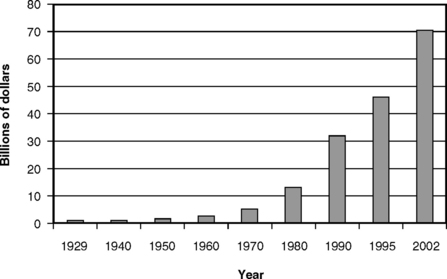

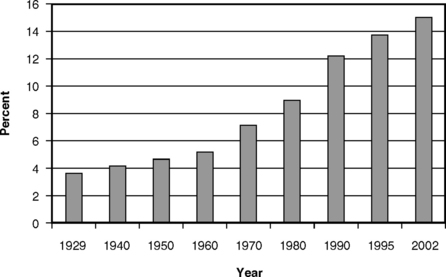

Expenditures for health care have risen sharply in all industrialized countries over the last several decades, but nowhere has this pattern been as pronounced as in the United States. Fig. 7-1 shows that, in 1929, expenditures in the United States for health care (including dental care) accounted for 3.6% of the gross domestic product (GDP). Since 1929, the amount has gone steadily upward, reaching 14.9% of GDP in 2002.26,57 Predictions suggest that spending for health care could rise to 20% of the GDP in the next few decades,23,66 a level of national expenditure that is a cause for deep concern.

Fig. 7-1 National health expenditures as a percentage of the gross domestic product in the United States, selected years, 1929-2002.26,36,57

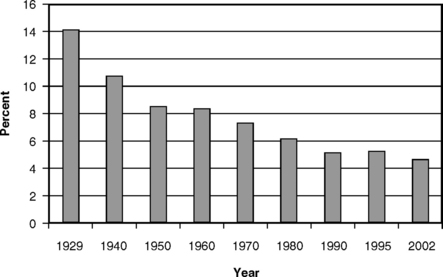

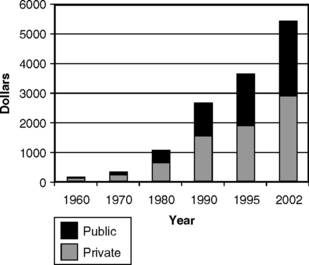

Fig. 7-2 shows how the per capita national health expenditures have risen since 1960. From an annual average of $141 in 1960, the average cost per person had risen to $5440 in 2002, a truly daunting figure.36,57 For insurance to be able to cover these kinds of costs, it is easy to see why premiums must be high. Fig. 7-2 also shows that the portion of the cost of health care paid by public funds has grown since 1960. In 2002, 46% of total national health expenditures were paid by public (government) funds.57 Some of the reasons given for this increase in the cost of health care in the United States include the following six factors:

Fig. 7-2 Per capita national health expenditures, showing the proportionate expenditure of private and public funds in the United States, selected years, 1960-2002.36,57

The Aging Population An aging population causes an increase in per capita costs. Because older people use more health care services, the average cost of care will increase as the average age of the population increases. In addition, the expectation of longer life brings a greater willingness to provide heroic care for a person who in earlier days would not have been expected to live much longer even if healthy, but who today is thought to have a reasonable chance for more high-quality years of life.

Developments in Technology Some innovations reduce the costs of care because they are so much more effective than any available alternatives (antibiotics, for example, reduced the average length of a hospital stay when they were introduced in the 1940s and 1950s). Others, because they are providing care that was previously unavailable, can only add to aggregate costs. An example is treatment for end-stage renal disease for patients who in earlier days would have soon died. With dialysis they now live, but at a cost that was estimated to average $24,976 per patient per year as long ago as 1983.48

The spiraling costs of health care present American society with a classic trade-off dilemma. On the one hand, if people go without health care that can improve or prolong their lives, both the individual and society suffer. On the other hand, it should be evident that the proportion of the GDP going to health care cannot continue to climb indefinitely, because as more of our available resources go to health care there is less for housing, education, recreation, and other necessities that contribute to health, wealth, and happiness. Although there is ample reason to be concerned for people who receive too little health care, there is also the possibility that a point can be reached at which, at least in the aggregate, there is too much health care relative to life’s other necessities. The dilemma is made even more difficult by the fact that, as of 2002, 43.6 million people in the United States had no health insurance.56 Although there is a justifiable outcry that some form of coverage should be provided for these people, it is also obvious that to do so will further increase national expenditures.30,42,78 Health care providers, in their honest desire to do the best for their patients, need to recognize that this tension between the individual and society will always exist.

EXPENDITURES FOR DENTAL CARE

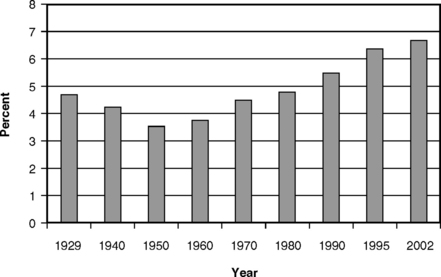

Expenditures for dental care, although only a fraction of the total for health care, are nevertheless substantial. Fig. 7-3 illustrates that the total expenditures for dental care by Americans grew from less than $500 million in 1929 to an estimated $70.3 billion in 2002.16,36,57 This latter figure represents an average per capita expenditure for dental care of $250 in 2002.

Figs. 7-4 and 7-5 present two additional views of the cost of dental care. Fig. 7-4 shows that, relative to the total cost of personal health care expenditures, dental expenditures have fallen steadily from the 14% reported in 1929 to 4.5% in 2002.26,57 This pattern reflects the combination of the steep rise in the overall costs of medical care and the more modest rise in the costs of dental care. Fig. 7-5 presents the expenditures for dental care as a percentage of the GDP. The pattern here is especially interesting: the relative decline from 1929 to 1950 corresponds to the period of the Great Depression followed by World War II. Dental care is income and price elastic, so that, as real income fell during the depression and as the cost of other goods and services rose during and after the war, there was simply less money available for dental care. The rise since 1970 coincides with a period of growth in real income and also in the extent of dental insurance. Economic theory suggests that both of these changes should result in a relative growth in dental expenditures, a phenomenon that has indeed occurred. The relative growth in dental expenditures has continued up to the present, to about 0.67% of the GDP in 2002, even though the percentage of the population covered by dental insurance has plateaued.57 This is a sign that the dental sector continues to be a robust part of the national economy.

FEE-FOR-SERVICE DENTAL CARE

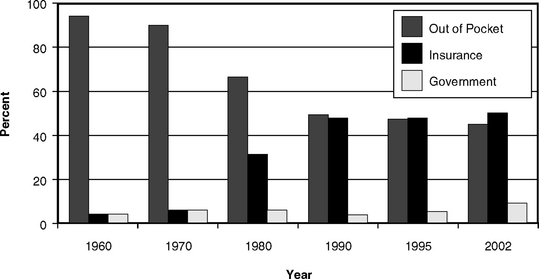

Private fee-for-service payment, the two-party arrangement, is the traditional form of reimbursement for dental services in the United States and elsewhere. Under this system, the patient decides when to visit a dentist, and the dentist suggests appropriate treatment and informs the patient of the fee for the service. If the patient chooses to follow the recommendations of the dentist and receives the services, the patient is then responsible for the fee. As shown in Fig. 7-6, as recently as 1970 almost all payments for dental services came directly from patients.36 However, by 2002, because of the substantial growth in prepayment, direct consumer payment had dropped to about 44% of all payments, with nearly 50% being paid by private insurance.57

THIRD-PARTY PAYMENT IN DENTISTRY

Growth of Third-Party Payment in Dentistry

In private third-party plans, periodic premiums are collected to meet the costs of providing care as well as the administrative costs of the third party. It has been argued that this arrangement should most properly be called prepayment rather than insurance, because it does not fulfill the classic definitions of insurance. Be that as it may, the term dental insurance has entered the language, and the terms dental prepayment and dental insurance as commonly used are virtually synonymous. The main difference between dental and some other forms of insurance is that traditional insurance involves a group of people making relatively small payments to cover the risk of a few suffering catastrophic loss, such as the loss of a home through fire. The expectation is that few of them will ever collect any insurance payments. Dental prepayment, on the other hand, is a mechanism to spread the financial load of dental care over a group and over time. Virtually all members of the group can reasonably expect to make regular and somewhat predictable use of the benefits.

By the late 1960s, with some 85% of the American population covered by hospital and surgical expense insurance,33 coverage for dental expenses emerged as a popular area for negotiation by labor groups seeking additional fringe benefits. Growth of dental prepayment plans through the 1970s and 1980s therefore can be seen as an evolutionary step in the growth of employment fringe benefits.

The rapid growth of prepayment since 1970 has changed the nature of dental practice. The growth is illustrated in Fig. 7-6, which shows that the portion of dental care costs paid by prepayment plans increased more than tenfold between 1970 and 2002. The proportion of the U.S. population covered by some sort of dental insurance increased from less than 5% in 1970 to well over one half by the turn of the century. Today it is a rare dental practice indeed that sees no insured patients at all. In many parts of the country, the majority of the patients in most practices have dental insurance.

Although the growth in dental insurance has been spectacular since 1970, further rapid growth in the immediate future is not likely. This is because members of the large unions in the major U.S. industries are, for the most part, already covered. For dental insurance to grow, mechanisms will have to be developed to reach small businesses and individuals. A second reason why dental insurance will grow only slowly is the general climate of cost control in all aspects of business, which in turn comes from the fierce demands on the United States to be competitive in the global economy. Increased concern for worldwide competitiveness works against offering benefits to workers not already covered, and there are already some signs of cutbacks in some industries. A third factor that may work against further expansion of dental insurance is the improvement in oral health, which is especially evident in young adults and children (see Chapters 19–21 Chapter 19Chapter 20Chapter 21). It may be that because people in these younger age cohorts have experienced little need for expensive and unexpected dental treatment, they will not push their employers as hard for dental insurance as did their elders, who had much higher levels of need for treatment.

Reimbursement of Dentists in Third-Party Plans

In line with its philosophy of maximizing practitioner independence, the ADA has consistently supported the concept of the UCR fee as a reimbursement method for dentists in prepayment plans. However, ADA resolutions that UCR fees should be the preferred method of reimbursement were rescinded on legal grounds after the U.S. Supreme Court decision in June 1975 in Goldfarb v. Virginia State Bar et al. This decision ruled that learned professions were not exempt from antitrust laws.5,7,8 In effect, the Court said that each practitioner should be free to choose how he or she wants to be reimbursed and that it was inappropriate for a professional association to suggest to its members which choice to make.

Usual, Customary, Reasonable Fee

The ADA definitions of usual, customary, and reasonable fees are as follows:

Table of Allowances

A table of allowances (or schedule) is defined as a list of covered services with an assigned dollar amount that represents the total obligation of the plan with respect to payment for such service but that does not necessarily represent the dentist’s full fee for that service.4 For example, if a dentist’s usual fee for a particular service is $20 and the plan lists a fee of $15 as payable for that service, the dentist will provide the service, collect $15 from the carrier, and may charge the patient $5 to make up the difference. Under the UCR fee method, on the other hand, the plan pays the dentist’s usual fee in full (less any required patient copayment), in this case $20. Use of a table of allowances as a method of reimbursement requires that dentists carefully explain to patients the limited nature of the insurance payment, because some patients are unaware that their plan may not cover the costs in full.

Fee Schedule

A fee schedule is defined as a list of the charges established or agreed to by a dentist for specific dental services.4 A fee schedule is usually taken to represent payment in full, whereas a table of allowances, as just explained, may not. With a fee schedule, the dentist must accept the listed amount as payment in full and not charge the patient at all. Fee schedules for dental care are sometimes established by public programs, such as Medicaid in many states. Dentistry’s opposition to fee schedules is based on (1) the potential inflexibility of such schedules, meaning that the fees listed can fall below customary fees, particularly in times of rapid inflation; (2) the implicit assumption that all dentists’ treatment is of the same quality and therefore worth the same fee; and (3) the fear that autonomy is threatened, especially if the fee schedule is not controlled by the dentists. A potential risk with use of a fee schedule is that, if the fees paid are too far below the usual level, few dentists will be willing to treat the covered patients. This has been cited as one reason why many dentists either severely limit the number of their Medicaid patients or refuse to accept such patients altogether.17,35,64

Capitation

Reimbursement of the dentist by capitation, as in a medical health maintenance organization (HMO), became more common during the 1980s and 1990s but plays a much smaller role in dentistry than it has in medicine. The ADA defines capitation as a dental benefit program in which a dentist or dentists contract with the program’s sponsor or administrator to provide all or most of the dental services covered under the program to subscribers in return for a payment on a per capita basis.4 A capitation fee is usually a fixed monthly payment paid by a carrier to a dentist based on the number of patients assigned to the dentist for treatment. Capitation requires that patients be assigned to specific dentists or dental practices for care, so that the capitation payment can be paid to the appropriate dentist or practice. This assignment is important, because the dentist receives a fixed sum of money per enrolled person per month, regardless of whether the participants in the plan receive care during that particular month. The assumption is that, although some patients will need a lot of care, others will need little or none, and therefore the total amount of money paid to the dentist will be sufficient to cover the overall costs of care for the covered group.

Many dentists are resistant to capitation because of a fear that high utilization and demands for expensive forms of care could rapidly outrun the capitation fee and that dentists will thus be at an economic disadvantage. As a dissenting voice, Schoen45–47 argued that capitation works every bit as well as fee for service and that with proper planning it is a highly efficient method of financing group dental care, especially for less affluent groups. Despite Schoen’s claims of success with capitation in his own group practice, however, many dentists and the ADA remain cautious. The ADA is opposed to capitation and fee schedules as the sole forms of reimbursement in prepayment plans, arguing that where such mechanisms exist they should be on an equal footing with UCR fees so that prospective patients have a choice. In fact, by the 1990s there were very few “pure” capitation plans. Most capitation plans now include copayments, especially for more expensive services, and annual maximums, both of which limit the economic risks faced by the dentist.

NOT-FOR-PROFIT DENTAL PLANS

Delta Dental Plans

In June 1954, the Seattle District Dental Society in Washington State was approached by the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union-Pacific Maritime Association with a request that the society submit a proposal for a comprehensive dental care program for the children of the union’s members up to 14 years of age. The proposal requested by the union required information on administration, fees, methods of operation, dental care provided, and control of quality. At that time there was almost no previous experience with plans of this type. The dental society nevertheless wished to discourage the union from setting up its own clinics, and it developed a plan whereby the children could be treated in the offices of private dentists. Shortly thereafter, the first dental service corporation was born.72 Within a few years dental service corporations were also formed in Oregon and California, and in subsequent years the idea of the dental service corporation spread throughout the country from the West Coast.

As the number of state dental association– sponsored service corporations increased through the early 1960s and the size of the groups for which dental care benefits were negotiated grew, the need for a national organization of dental service organizations became apparent. Accordingly, the National Association of Dental Service Plans was formed in 1966, with staff and financial help from the ADA. The name became Delta Dental Plans Association (DDPA) in 1969,28 and most of the member corporations became known as the Delta Dental Plan for the particular state.

DDPA has also become the vehicle through which the Delta plans in individual states compete with national for-profit insurance companies for contracts with companies with employees in more than one state. Through DDPA, an organization called DeltaUSA was formed to coordinate and administer these multistate contracts. In 2003 more than 108,000 participating dentists were available to DeltaUSA through the individual state Delta plans, accounting for at least 70% of all dentists in practice nationwide. Collectively, Delta plans cover approximately 42 million people in the United States.18

The underlying philosophy of the Delta Dental Plans was to permit dental practitioners to adapt their traditional patterns of practice to meet the demand for group purchase of dental care. In this sense, Delta plans have followed the lead of the professionally sponsored Blue Cross and Blue Shield hospital and medical plans. Most Delta plans were formed for the sole purpose of providing dental prepayment, and most have retained dental insurance as their sole or major business.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses