7

Behavior Management and Medical Emergencies

Case 1

Non-pharmacological Behavior Management

A. Presenting Patient

- 5-year-, 10-month-old Hispanic female

B. Chief Complaint

- Mom states, “My daughter needs a check up”

C. Social History

- Parents are married

- Mother is the primary caregiver and does not work outside the home, father is a construction worker

- Lower socio-economic status

- One brother, age 4

- The child does not participate in activities outside the home

D. Medical History

- Review of systems is negative

- No allergies to medication, mild seasonal allergies

- No routine medications

- No previous hospitalizations or surgeries; no emergency room visits

E. Medical Consult

- Not necessary at this time

F. Dental History

- This is the patient’s first comprehensive dental visit. She has been examined at a dental screening in a nearby community center. Patient was uncooperative for exam but mother was told the patient had no decay

- Patient lives in a fluoridated community and uses city water• Brushes unsupervised twice daily with fluoridated toothpaste. Patient “does not allow” mother to assist with brushing

- Highly cariogenic diet with frequent snacks and juice

- No previous dental treatments

- No history of dental trauma or habits

- Parents and siblings have not had any dental care in “several years”

- Patient clings to the parent as they are escorted to the operatory. Patient barely speaks to members of the dental team

- The functional inquiry consists of the following questions:

- How do you think your child has reacted to past medical procedures?

- How would you rate your own anxiety (fear, nervousness) at this moment?

- Does your child think there is anything wrong with his or her teeth, such as a chipped tooth, decayed tooth, gum boil?

- How do you expect your child to react in the dental chair?

G. Extra-oral Exam

- Head and neck: Within normal limits

- Weight and height, BMI: Within normal limits

- Exposed extremities (bruising, etc.): Within normal limits

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- Within normal limits

Hard Tissues

- Occlusal caries on teeth S and L, good spacing with no interproximal caries noted

Dentition

- Full primary dentition

Occlusion

- Mesial step with normal overjet and overbite

- Child should be welcomed in to a child friendly environment

- There is a triangular relationship between the dentist, the child and the family

- Functional inquiry should be part of the history form: negative response to more than one question increases the chance of encountering a behavior problem

- Consider the communication advantages of having the parent in the operatory:

- Parent can see firsthand how the child behaves

- Parent may be able to facilitate communication, especially with a special needs child or when language is an issue

- Very young children may not separate easily from the parent

- Consider the communication disadvantages of having the parent in the operatory:

- Parent can interfere with communication between the dentist and the child

- The child may divide her attention between the dentist and the parent

- The child may be less willing to cooperate with the dentist when the parent is present

I. Diagnostic Tools

- No additional diagnostics were obtained

J. Differential Diagnosis

- N/A

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Early childhood caries

Problem List

- Fearful patient

- Poorly compliant parent

- Poor diet

- Poor oral hygiene

- No dental home

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Establish dental home

- Establish aggressive caries prevention plan

- Restore decay on teeth S and L using appropriate behavior management

- Recall on three-month interval

M. Prognosis and Discussion

- The child is apprehensive during the examination but will sit in the chair by herself with the mother sitting nearby. The patient follows instructions to open and close mouth but with apprehension and some crying. The tell-show-do method should be effective in this situation

- See Figures 7.1.1 through 7.1.4

- Tell the patient what to expect using phrases that are appropriate to the developmental level

- Show the procedure or instrument in a non-threatening manner

- Perform the procedure without deviating from the explanation and reminding the patient of the previous explanations and demonstrations

- Use controlled modulation of voice volume to direct the patient’s behavior. This technique should be described to parents unfamiliar with its use

- Reward positive behavior through social (voice tone) and non-social (tokens, prizes) reinforcement

- Divert the patient’s attention from what may be perceived as an unpleasant experience. This can be visual (watching a movie) or auditory (listening to music or a story)

AAPD (2011–12)

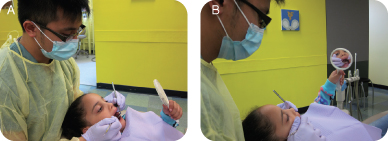

Figure 7.1.1a–b. Tell-show-do. A mirror is used while telling the patient what to expect

Figure 7.1.2. Tell-show-do. Dentist tells patient what to expect

Figure 7.1.3. Tell-show-do. Dentist shows patient what to expect

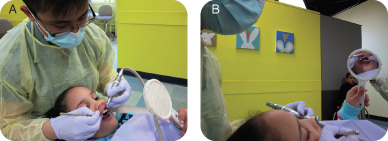

Figure 7.1.4a–b. Tell-show-do. Dentist does what patient expects while patient watches in mirror. Note anxious sibling in background

Figure 7.1.5. Modeling. Dentist demonstrates while sibling watches

N. Common Complications and Alternative Treatment Plans

- Despite her initial cooperation, the patient could became uncooperative and combative later on. If this occurs, then other forms of behavior management may need to be considered

Self-study Questions

1. What are the important questions to ask to assess the possible behavior of the patient?

2. How do you accomplish tell-show-do?

3. What are the advantages and disadvantages of having a parent in the operatory?

4. Should the dental team be trained in behavior management skills? Why?

5. What are the options available for behavior management if communication methods fail?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2011–2012. Reference Manual, Guideline on Behavior Guidance for the Pediatric Dental Patient, 33(6):161–73.

Wright GZ, Stigers J. 2010. Non-pharmacolgical management of children’s behavior. In Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent, 9th Edition. McDonald R, Avery D, Dean J (eds) Mosby: Maryland Heights, MO.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. It is important to ask questions in the functional inquiry about behavior at previous medical or dental visits, parental anxiety about dentistry, the child’s perception of her oral health, and how the parents expect the child to behave. It is also helpful to ask about child development status, behavior in daycare or preschool, and previous dental experiences of parents and siblings

2. First tell the patient what is going to be done, then demonstrate the action, and then perform the procedure and simultaneously explain it

3. The advantages of having a parent in the operatory are that the parent can see firsthand how the child behaves, the parent may be able to facilitate communication—especially with a disabled child—and very young children may not separate from the parent. The disadvantages are that the parent can interfere with communication between the pediatric dentist and the child, the child may divide her attention between the dentist and the parent, and the dentist may divide his attention between the child and the parent. Sometimes the child may not be as willing to cooperate with the dentist’s instructions when the parent is present

4. The dental team should be trained in behavior management techniques because the staff is an extension of the dentist. This allows the dental team to work together to communicate with the child

5. If communication methods fail, protective stabilization or pharmacological methods can be considered

Case 2

Pharmacological Behavior Management

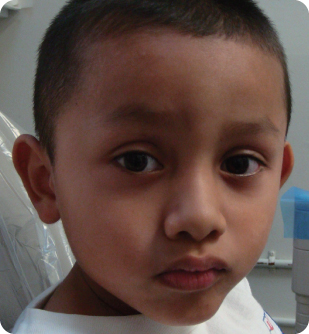

Figure 7.2.1. Facial photograph

A. Presenting Patient

- 4-year-, 10-month-old Hispanic male

B. Chief Complaint

- Mom states, “My son is here to have his cavities fixed with sedation”

C. Social History

- Mother is the primary caregiver

- Patient lives with parents and one brother, age 10

- Mother works full-time outside the home; father is unemployed

- Lower socio-economic status

- Patient does not participate in any sports

D. Medical History

- Review of systems is negative

- No known allergies to any foods or medications

- No medications

- Hospitalization at age 3 for dental treatment under general anesthesia

- American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I

- When reviewing the patient’s medical history and performing an assessment of the patient’s general health on the day of sedation, keep in mind that the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) uses a physical status classification system which serves as a risk assessment

- A careful pre-sedation evaluation for underlying health conditions that would place the patient at an increased risk for complications during sedation must be completed

- Only patients who are ASA I are routinely accepted as appropriate candidates for in-office moderate sedation

- Patients who are ASA II or III require consultation with the patient’s primary care provider to identify any concerns regarding the administration of sedation medications

- Patients who are ASA III typically are treated in the hospital setting with anesthesiologists to manage potential complications

- Class I: Normal healthy patient

- Class II: Patient with mild systemic disease

- Class III: Patient with severe systemic disease

- Class IV: Patient with a severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life

- Class V: Moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation

- See http://www.asahq.org/clinical/physicalstatus.htm for the complete ASA classification system

E. Medical Consult

- Not necessary at this time

F. Dental History

- Highly cariogenic diet with frequent sugared soft drinks and snacks

- Patient lives in a fluoridated community using city water, and mom states the child brushes his teeth once every day with fluoridated toothpaste without supervision; does not floss

- Patient was treated for full mouth dental rehabilitation under general anesthesia in the ambulatory care center at age 3. Treatment also included surgical repair of a left mandibular abscess that had resulted in left facial cellulitis

- After the initial post-operative follow-up appointment the patient did not return for recall visits

- No history of trauma

- Patient is uncooperative and extremely anxious, clinging to his mother

- As stated by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the goals of sedation for children undergoing diagnostic and therapeutic procedures include:

- Ensure the patient’s safety and welfare

- Minimize discomfort and pain

- Control anxiety and minimize psychological trauma

- Maximize amnesia

- Control behavior or patient movement so the procedure can be completed safely

- Return the patient to the pre-sedation level to allow for safe discharge from medical supervision

- The provider shall obtain and document appropriate informed consent according to local, state, and institutional requirements

G. Extra-oral Exam

- Head and neck: Within normal limits

- Weight and height, BMI: Within normal limits

- Exposed extremities: Within normal limits, negative for bruising

- Other: Heart sounds normal, breath sounds clear with no evidence of upper respiratory infection

- Patient has not taken any food or liquid by mouth (NPO) since midnight

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- Within normal limits, Brodsky scale 2

Hard Tissues

- Multiple severe carious lesions

Dentition

- Primary dentition

Occlusion

- Crossbite on right

I. Diagnostic Tools

- Bitewing radiographs

J. Differential Diagnosis

- N/A

K. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Recurrent early childhood caries

Problem List

- No dental home

- Poor oral hygiene and diet

- Uncooperative and exhibits situational anxiety

L. Comprehensive Treatment Plan

- Establish dental home

- Implement aggressive caries prevention plan

- Due to anxiety and the extent of the restorations, treatment will require the use of oral sedative medications in conjunction with nitrous oxide to assure the patient’s comfort level and tolerance of the procedure

- To help minimize the potential for airway obstruction in children receiving oral sedation medications, an airway assessment must be completed prior to sedation to check for airway abnormalities or large tonsils

- The Brodsky scale indicates how much space the tonsillar tissue occupies in the pharyngeal area

- Patients with a Brodsky of +3 (meaning the tonsillar tissue takes up more than 50% of the pharyngeal space) are at an increased risk of developing airway obstruction (see example in Figure 7.2.2)

- Patients with a Brodsky of +3 or greater should be considered for alternative pharmacologic management, i.e., general anesthesia or no sedation to maintain a patent airway

McDonald et al. (2004)

Figure 7.2.2. Example of a patient with Brodsky of +3

Post-op Care

- Minimize vigorous activity for the patient

- Pay attention to lip numbing while the patient attempts to eat

- Maintain a bland and soft diet for the day

- Follow-up visit in two weeks

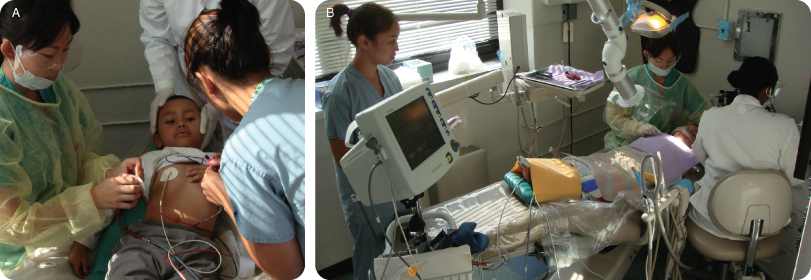

- Continuous monitoring of oxygen saturation and heart rate, and intermittent recording of respiratory rate and blood pressure that should be recorded on a time-based record

- Frequent checking of restraint devices to prevent airway obstruction or chest restriction

- Frequent checking of the patient’s head position to ensure airway patency

- Presence of a functioning suction apparatus

- Monitoring requirements depend on the level of sedation. Minimal, moderate, and deep sedation all have different monitoring guidelines

- To achieve the goals of sedation in children while minimizing adverse events, the lowest dose of a drug with the highest chance of success for the procedure should be chosen

- For painful procedures, include an analgesic such as an opiod like Meperidine

- For non-painful procedures, a sedative can be used, such as a benzodiazepine like Midazolam (Versed®). A sedative hypnotic also can be used, such as Chloral Hydrate

- For procedures that require both sedation and analgesia, choose either single agents with both sedative/analgesic properties, or combination drug therapy

- Anxiolysis and amnesia are also considered when choosing drug regimens

- The more drugs that are mixed, the greater the chance of adverse events such hypoventilation, apnea, or airway obstruction

- Benzodiazepines are commonly used as amnestics in the outpatient sedation of children

- Benzodiazepines enhance the binding of GABA, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system

- Benzodiazepines produce sedation, anxiolysis, amnesia, and suppression of seizure activity

- At moderate doses, patients who have received benzodiazepines will be conscious, yet sedate, and will not remember the procedure

- At high doses, benzodiazepines will result in unconsciousness and loss of protective airway reflexes

- Common benzodiazepines include Midazolam (Versed®) and Diazepam (Valium®)

- When combined with narcotics, the respiratory depressant effects are synergistic

- Benzodiazepines produce little direct cardiovascular effects

- The main opioid receptors are Mu1 and Mu2

- Analgesia occurs through Mu1 receptors

- Respiratory depression, bradycardia, and euphoria occur through Mu2

- Meperidine is commonly used in the outpatient sedation of children, usually in combination with Versed® or Chloral Hydrate

- There tends to be less respiratory depression with meperidine than morphine in children, but each child responds differently, so monitoring is essential

- Chloral hydrate is considered an older sedative hypnotic, an alcohol by structure

- Commonly used, inexpensive, and well absorbed by mouth (PO), it has minimal effects on respiration, with sedation in about 30 to 45 minutes

- It is NOT an analgesic

- Sedation can result in airway obstruction, especially in the presence of large tonsils

- Chloral Hydrate tastes bad and can cause nausea and vomiting

M. Prognosis and Discussion

- Based on the history, this child has a high likelihood of caries recurrence

- Patient has already required a general anesthesia appointment and sedation to treat caries

- An aggressive prevention plan should be implemented

- The parent should be advised that routine recall visits of at least three months interval are necessary to maintain the patient’s oral health and monitor home care. These less invasive visits will provide an opportunity to reduce anxiety about dental visits

- Children should be monitored as they recover from sedation. Do not be fooled by thinking that just because the dentistry is done, the child is recovered. With the loss of surgical stimuli, the child may actually become more sedated

- Children are ready to be discharged if at least the following criteria are met:

- Pre-sedation level of consciousness is attained

- Respiratory rate and rhythm, heart rate, and oxygen saturation are within normal limits

- Pre-sedation level of ambulation is attained

- Patient can swallow oral fluids; demonstrates return of gag reflex or cough

- Patient has no nausea, vomiting, dizziness

- Medications with a longer half life may require longer periods of supervised recovery due to the possibility of resedation

- Patients who have received reversal agents also require a longer period of supervised recovery because the sedative medication tends to last longer than the reversal agent, posing a potential for resedation

N. Common Complications and Alternative Treatment Plans

- What are your options if the oral sedative medications fail to adequately control the patient’s anxiety and movement during the case?

- What is the appropriate intervention if the patient becomes apneic?

Figure 7.2.3a–b. Patient with monitors and protective stabilization during sedation

Self-study Questions

1. What important history and physical observations are required before administering sedative medications to a patient?

2. To minimize risk to the pediatric dental patient receiving sedation, what are the requirements of a safe environment for in-office administration of sedation?

3. What are some of the potential complications of sedation in the office that the provider should be prepared to handle?

4. What are the different types of sedation available to patients, provided the dentist has the proper educational qualifications?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry. 2011–2012. Clinical Guideline for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures. Reference manual. Pediatr Dent 33(6):185–201.

Coté CJ, Ryan J, Todres ID, Goudsouzian NG. 2001. A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children, 3rd edition. W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia.

Duke J, Rosenburg SG. 1996. Anesthesia Secrets. Hanley and Belfus, Inc.: Philadelphia.

Katzung BG. 1998. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology, 7th edition. Appleton and Lange: Stamford.

McDonald RE, Avery DR, Dean JA. 2004. Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent, 8th edition. Mosby: St. Louis.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses