4

Orofacial Trauma

Case 1

Intrusion Injury to Primary Dentition

Figure 4.1.1. Facial photograph

A. Presenting Patient

- 2-year-, 7-month-old male

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint and History of Present Injury

- Mother stated, “My son was running and hit the stairs in our house”

- Child was running in home, fell and hit cement stairs three hours ago. Injury was witnessed by mother, who said that child “spit up food” after injury. No loss of consciousness

- Child was taken to local emergency room and cleared of any closed head trauma

- Child is in no distress

C. Social History

- Patient is only child

- Mother is the primary caregiver and stays at home

- Low socio-economic status

D. Medical History

- History of recurrent otitis media infections per mother

- No known drug or food allergies, no medications, vaccinations are up to date

- Confirm that tetanus immunizations are up to date. If last tetanus booster was five or more years prior and wound is contaminated with soil/debris, another tetanus toxoid booster is indicated (Broder et al. 2006, McTigue and Thikkurissy 2011)

- Rule out closed head injury and refer for medical consult if patient is positive for any of the following (CDC 2007):

- Amnesia

- Nausea/vomiting

- Headache

- Lethargy/irritability/confusion

- Loss of consciousness

- The preschool years represent a peak in incidence of dental trauma, with some reports citing incidence as high at 35% (Hargreaves et al. 1999)

E. Medical Consult

- Completed at the emergency room

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- Fair oral hygiene; mother states she brushes his teeth every day

- Age-appropriate diet

- Uses toothpaste containing fluoride

- Optimally fluoridated water

- No history of trauma before today

- Child is acting age-appropriately, resisting being separated from mother

G. Extra-oral Exam

- Soft tissue injuries: Bruising noted on lip

- No other significant findings

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- No significant findings

Hard Tissues

- No significant findings

Occlusal Evaluation of Primary Dentition

- Mesial step molar and class I canines

Other

- Minimal plaque accumulation noted

- Caries-free dentition

- Maxillary right primary lateral incisor: Slight mobility, brown discoloration noted middle third

- Maxillary right primary central incisor: Slight mobility

- Maxillary left primary central incisor: Intruded to gingival margin (Figure 4.1.2.)

- Maxillary left primary lateral incisor: Slight mobility, brown discoloration noted middle third

Figure 4.1.2. Intra-oral photo showing intrusion of maxillary left primary central incisor

I. Diagnostic Tools

- Radiographs not possible due to very poor patient cooperation

- Vitality tests deferred

- Rule out other injuries, e.g., root fractures, alveolar fracture, etc.

- Vitality testing of questionable value on primary teeth and recognition of pulpal necrosis is typically based on clinical presentation (Pugliesi et al. 2004)

- Lateral occlusal film (Figure 4.1.3) is taken by attaching a large occlusal film to a tongue depressor and having the child bite on the depressor, which may also aid in collumnation. An alternative, if the child is too young to bite or is uncooperative, is to have parent sit on chair, with both the parent and child shielded, and have the parent hold the film on the child’s cheek

- The clinical exam of this patient revealed intrinsic brownish discoloration. There are several theorized sources of tooth discoloration in children including systemic illness and certain medications. While some dental staining, such as those due to tetracycline, are well-documented, others such as extrinsic amoxicillin-clavulanic acid staining are less studied and subsequently less thoroughly understood (Garcia-López et al. 2001)

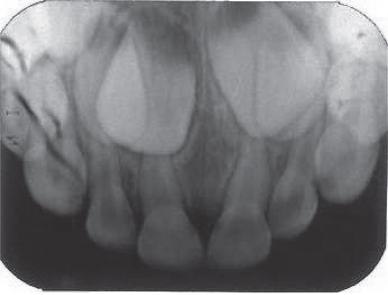

Figure 4.1.3. Example of technique for extra-oral lateral occlusal radiograph

J. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Maxillary right primary lateral incisor, right primary central incisor, and left primary lateral incisor: Subluxation

- Maxillary left primary central incisor: Intrusion

Problem List

- No dental home

- Complete intrusion maxillary left primary central incisor

K. Treatment

- No treatment is indicated at this time (see Flowchart A at the end of this chapter)

- Advise parent of potential damage to permanent tooth bud, including potential hypocalcifications

- Discharge instructions

- Avoid incising on injured segment until instructed otherwise

- Watch for clinical signs such as presence of parulis or fistula

- Follow-up treatment

- Patient was seen for follow-up at one and two months with minimal re-eruption noted

- Four-month follow-up: Per mother, patient is asymptomatic; the maxillary left primary central incisor has fully re-erupted into position

Figure 4.1.4. Intra-oral photo showing re-eruption of maxillary left primary central incisor

Figure 4.1.5. Radiograph showing no periapical resorption or radiolucency associated with the maxillary left primary central incisor

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- The overall prognosis for this tooth is based on the observation that it did re-erupt. The four-month post-op radiograph demonstrated no periapical resorption or radiolucency. The full understanding of the impact of the trauma is limited to the two-dimensional radiograph, and the successful eruption of the permanent incisor is a benchmark for the overall success of treatment

- Trauma to primary teeth can lead to developmental or hypoplastic defects in permanent successors (Figure 4.1.6) (Sennhenn-Kirchner and Jacobs 2006)

- The majority of intruded primary incisors are displaced in a labial direction (Holan and Ram 1999)

- All teeth involved in injury must be re-assessed for potential pulpal injury, which may not surface immediately (Flores et al. 2007)

- The majority of intruded primary incisors (88% in some reports) will re-erupt within six months (Holan and Ram 1999)

- When there is no impingement on the permanent tooth bud, or the facial cortical plate has not been fractured, a wait-and-watch approach may be most prudent because most incisors will re-erupt within six months

Figure 4.1.6. Example of hypoplastic defects (arrows) of the permanent successors following intrusion trauma to the primary incisors

M. Complications and Alternative Treatment Plan

- If the root tip had become exposed through gingival tissues, extraction would be indicated due to the poor healing prognosis

- If the tooth failed to re-erupt after six months of evaluation, an extraction would be the recommended course of treatment because any partial ankylotic changes could impede the path of eruption of the permanent incisor

- It is not unusual to have a concomitant root fracture on a primary incisor. If the coronal fractured segment poses any type of aspiration risk, then the recommendation is extraction of the coronal segment while leaving the apical segment alone

Self-study Questions

1. What are instances in which immediate extraction of intruded primary incisors would be indicated?

2. How long should one wait and watch intruded primary incisors to re-erupt?

3. If the intruded tooth is asymptomatic at one week post injury, is the pulp healthy?

4. If a root fracture was present in the apical one-third of the root, is it recommended to surgically extract the remaining root tip?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography

Broder K, Cortese M, et al. 2006. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: Use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines. Recommendations of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization practices. MMWR. Feb. 23, 2006, 55:1–43. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr55e223a1.htm and http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/tetanus/default.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007. Heads Up. Facts for Physicians about Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI). http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/Facts_for_Physicians_booklet.pdf.

Flores MT et al. 2007. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. III. Primary teeth. Dent Traumatol 23:196–202.

Garcia-López M, Martinez-Blanco M, Martinez-Mir I, Palop V. 2001. Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid-related tooth discoloration in children. Pediatrics. Sep;108(3):819.

Hargreaves JA, Cleaton-Jones PE, Roberts GJ, Williams S, Matejka JM. 1999. Trauma to primary teeth of South African pre-school children. Endod Dent Traumatol Apr;15(2):73–6.

Holan G, Ram D. 1999. Sequelae and prognosis of intruded primary incisors: a retrospective study. Pediatr Dent Jul-Aug;21(4):242–7.

McTigue D, Thikkurissy S. 2011. Trauma. In: The Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry, 4th Edition. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS (eds). American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago. pp. 109–17.

Pugliesi DM, Cunha RF, Delberm AC, Sundefeld ML. 2004. Influence on the type of dental trauma on the pulp vitality and the time until treatment: a study in patients ages 0–3 years. Dent Traumatol Jun;20(3).139–42.

Sennhenn-Kirchner S, Jacobs HG. 2006. Traumatic injuries to the primary dentition and effects on permanent successors—a clinical follow-up study. Dent Traumatol Oct;22(5):237–41.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. If a radiograph, such as a lateral occlusal, indicates that the primary tooth is intimately associated with the permanent tooth bud, extraction may be indicated. Any potential aspiration risk to the child is also an indication for extraction. Extraction of the intruded incisor does not necessarily spare the successor from possible damage

2. While reports note that the majority of intruded primary incisors will re-erupt within six months, re-eruption should be assessed monthly and teeth should demonstrate significant re-eruption (although not necessarily complete) by two months. If there is no evidence of re-eruption, then a careful clinical and radiographic examination must be completed to re-assess treatment options such as extraction

3. No. In the instance of any traumatic injuries, the pulp may provide false-positive responses clinically for up to three weeks post injury. Sequelae such as replacement resorption may not be apparent until six weeks post injury.

4. If the remaining root tip is intimately related to the permanent tooth bud, then any treatment must be approached with the understanding that there is potential for damaging the permanent tooth as well

Case 2

Root Fracture in the Primary Dentition

Figure 4.2.1. Facial photograph

A. Presenting Patient

- 4-year-, 6-month-old Caucasian male

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint and History of Present Injury

- Mom states, “My son knocked his teeth yesterday, and now they look brownish.” The child was playing at the mall playground and fell. The injury was witnessed by the mother. There was no loss of consciousness and no complaint of pain

- While many parents may believe that their children are taking preventive measures to avoid injury, such as bicycle helmets, the truth is that reports by children often reveal that when unsupervised, injury prevention measures are often not followed (Ehrlich et al. 2001)

- Studies have revealed that mouth guards are an effective primary protective measure at reducing the rate of dento-alveolar injuries, yet in some instances only 1% to 5% of children participating in sports actually wear mouth guards during practices (Spinas and Savasta 2007, Fakhruddin et al. 2007).

- Falls are typically the most common type of injury, and while the anecdotal belief is that increased supervision will prevent injuries, reports in the literature cite that only about 20% of parents believe increased supervision will prevent falls/injuries (Eberl et al. 2009)

- There is a reported peak in incidence of dental trauma during preschool years of as high as 35% (Hargreaves et al. 1999)

C. Social History

- Patient has no siblings

- Mother is the primary caregiver and stays at home

- Low socio-economic status

D. Medical History

- History of recurrent otitis media infections

- No known drug or food allergies, no medications, vaccinations are up to date

- Confirm that tetanus immunizations are up to date. If the last tetanus booster was five or more years prior and the wound is contaminated with soil/debris, another tetanus toxoid booster is indicated (Broder et al. 2006, McTigue and Thikkurissy 2011)

- Rule out closed head injury and refer for medical consult if the patient is positive for any of the following (CDC 2007):

- Amnesia

- Nausea/vomiting

- Headache

- Lethargy/irritability/confusion

- Loss of consciousness

E. Medical Consult

- N/A

F. Dental History

- Child has seen dentist since 18 months of age

- Fair oral hygiene with little adult supervision. Mild plaque accumulation on buccal surfaces of maxillary molars

- Diet is age appropriate

- Uses toothpaste containing fluoride twice daily

- Lives in optimally fluoridated area

- No history of trauma before today

- Child’s behavior is age appropriate, and he is curious about dental instruments

Figure 4.2.2. Intra-oral photo of maxillary right and left primary central incisors

G. Extra-Oral Exam

- Soft tissue injuries: mild contusions on upper lip

H. Intra-Oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- No significant findings

Hard Tissues

- Traumatized teeth: Maxillary right and left primary central incisors—class I mobility

Occlusal Evaluation of Primary Dentition

- No significant findings

Other

- Caries-free dentition

I. Diagnostic Tools

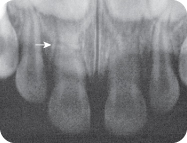

- Periapical radiograph shows root fracture in the middle third of the maxillary right and left primary central incisors

- Vitality tests deferred

- Take adequate radiographs to clearly image all involved teeth.

- Rule out other injuries, e.g., soft tissue lacerations, alveolar fractures, etc. (Flores et al. 2007)

- Vitality testing is of questionable value on primary teeth, and recognition of pulpal necrosis is typically based on clinical presentation (Pugliesi et al. 2004)

Figure 4.2.3. Radiograph showing root fractures of maxillary right (arrow) and left primary central incisors

J. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Maxillary right and left primary lateral incisors: subluxation

- Maxillary right and left primary central incisors: middle root fractures

K. Treatment

- No treatment is indicated at this time (see Flowchart B at the end of this chapter)

- Discharge instructions: Avoid incising on injured segment until instructed otherwise. Watch for clinical signs such as presence of parulis or fistula

- Follow-up treatment: Follow up within four weeks to reassess healing and potential need for future treatments.

- Root fractures traditionally heal by one of four means:

- The most common forms of root fracture healing are calcified tissue and interposition of connective tissue (Cvek et al. 1995)

- Splinting primary teeth should be attempted only after careful risk:benefit analysis, including:

- While some studies have shown success with primary tooth splinting, medico-legal considerations must be discussed with caregivers

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- Root fractures located on the apical third present a good prognosis. Teeth with root fractures in the middle segment should be observed closely as in the case presented. The more coronal the fracture is, the worse the prognosis. Cases in which there is significant mobility of the coronal segment and/or mobility of the coronal segment result in poor outcomes

M. Complications and Alternative Treatment Plan

- If the fracture had been located in the coronal third, the recommendation would be to remove the coronal segment because the prognosis is poor. There is some controversy as to whether apical segments need to be removed. Direct visualization of the apical segment would facilitate extraction, while poor or no visualization could result in damage to permanent tooth bud

- Tooth discoloration is a common post-traumatic complication

- Dark gray discoloration of primary incisors soon after injury may fade and does NOT warrant immediate treatment

- Discoloration noted soon after injury is not representative of definitive pulpal diagnosis (Holan 2004)

- Tooth discoloration that first appears well after the trauma may be indicative of changes in pulp vitality and potential necrosis (Soxman et al. 1984)

- All teeth involved in injury must be re-assessed for potential pulpal injury (Flores et al. 2007)

Self-study Questions

1. What are the situations in which extraction of tooth and/or segments is warranted?

2. Would management differ if discoloration had occurred 26 months after injury?

3. When is splinting of primary teeth indicated?

Answers are located at the end of the case.

Bibliography

Broder K, Cortese M, et al. 2006. Preventing tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis among adolescents: Use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccines. Recommendations of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization practices. MMWR. Feb. 23, 2006, 55:1–43. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr55e223a1.htm and http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/tetanus/default.htm.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2007. Heads Up. Facts for Physicians about Mild Traumatic Brain Injury (MTBI). http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc/tbi/Facts_for_Physicians_booklet.pdf.

Cvek M, Andreasen JO, Borum MK. 1995. Healing of 208 intra-alveolar root fractures in patients aged 7–17 years. J Endod Jul;21(7):391–3.

Eberl R, Schalamon J, Singer G, Ainoedhofer H, Petnehazy T, Hoellwarth ME. 2009. Analysis of 347 kindergarten-related injuries. Eur J Pediatr 168:163–6.

Ehrlich PF, Longhi J, Vaughan R, Rockwell S. 2001. Correlation between parental perception and actual childhood patterns of bicycle helmet use and riding practices: implications for designing injury prevention strategies. J Pediatr Surg May;36(5):763–6.

Fakhruddin KS, Lawrence HP, Kenny DJ, Locker D. 2007. Use of mouthguards among 12- to 14-year-old Ontario schoolchildren. J Can Dent Assoc Jul-Aug;73(6):505.

Flores MT, et al. 2007. Guidelines for the management of traumatic dental injuries. III. Primary Teeth. Dent Traumatol 23:196–202.

Hargreaves JA, Cleaton-Jones PE, Roberts GJ, Williams S, Matejka JM. 1999. Trauma to primary teeth of South African pre-school children. Endod Dent Traumatol Apr;15(2):73–6.

Holan G. 2004. Development of clinical and radiographic signs associated with dark discolored primary incisors following traumatic injuries: a prospective controlled study. Dent Traumatol Oct;20(5):276–87.

McTigue D, Thikkurissy S. 2011. Trauma. In: The Handbook of Pediatric Dentistry, 4th Edition. Nowak AJ, Casamassimo PS (eds) American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry: Chicago. pp. 109–17.

Pugliesi DM, Cunha RF, Delberm AC, Sundefeld ML. 2004. Influence on the type of dental trauma on the pulp vitality and the time until treatment: a study in patients ages 0–3 years. Dent Traumatol Jun;20(3).139–142.

Soxman JA, Nazif MM, Bouquot J. 1984. Pulpal pathology in relation to discoloration of primary anterior teeth. ASDC J Dent Child Jul–Aug;51(4):282–4.

Spinas E, Savasta A. 2007. Prevention of traumatic dental lesions: cognitive research on the role of mouthguards during sport activities in paediatric age. Eur J Paediatr Dent Dec;8(4):193–8.

SELF-STUDY ANSWERS

1. As the fracture is placed more coronally, the prognosis worsens for the tooth. Furthermore, the aspiration risk must be assessed. Parents should be made aware of the possibility for the need to remove the coronal and/or entire segment at a later date if no treatment is immediately rendered

2. Per the 2007 International Association of Dental Traumatology (IADT) guidelines (http://www.iadt-dentaltrauma.org), transient discoloration immediately following injury is not uncommon. This discoloration is most often reddish or grayish. Discoloration that occurs well after the traumatic injury may be indicative of pulpal necrosis and result in inflammatory resorption despite the patient remaining asymptomatic

3. Splinting primary teeth should be attempted only after careful risk:benefit analysis, including patient cooperation and behavior, ability for adequate isolation if a resin splint is used, and parental compliance and understanding of the need for follow-up care. While some studies have demonstrated success with splinting primary teeth, full medico-legal considerations need to be discussed with parents/caregivers

Case 3

Complicated Crown Fracture, Permanent Tooth

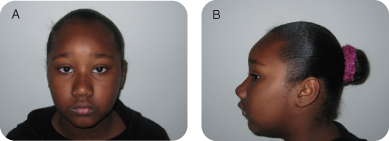

Figure 4.3.1a–b. Facial photographs

A. Presenting Patient

- 8-year-, 7-month-old African-American female

- New patient presenting as an emergency

B. Chief Complaint and History of Present Injury

- Mother reports, “My daughter fell off her bicycle and broke her tooth.”

- Child fell while riding her bike at her grandmother’s house about three and a half hours ago. The grandmother had no transportation so the patient waited until her mother returned home from work to come to the clinic. The accident was witnessed by her 12-year-old cousin. There was no loss of consciousness.

- Rule out closed head injury and refer for medical consult if patient is positive for any of the following (CDC 2007):

- Amnesia

- Nausea/vomiting

- Headache

- Lethargy/irritability/confusion

- Loss of consciousness

- Ask patient and parent if they know where the broken tooth fragment is. Rule out aspiration or impaction of the fragment in soft tissue wounds of the lips or tongue

- Confirm that tetanus immunizations are up to date if there are soft tissue injuries contaminated with soil (Broder et al. 2006)

C. Social History

- Patient is in third grade

- Lives at grandmother’s house with mother, one younger sibling, and two cousins

- Mother works two jobs and provides for all in household; the grandmother is the primary care provider

- Low socio-economic status

D. Medical History

- No significant findings, no known food or drug allergies, no medications, vaccinations are up to date

E. Medical Consult

- N/A

F. Dental History

- No dental home

- Mother reports infrequent dental exams through local school program

- Diet high in refined carbohydrates

- Poor oral hygiene

- Child reports brushing with fluoridated toothpaste once per day

- Community water is optimally fluoridated

- No previous history of dental trauma

G. Extra-oral Exam

- No significant findings

H. Intra-oral Exam

Soft Tissues

- No significant findings

Hard Tissues

- No obvious carious lesions

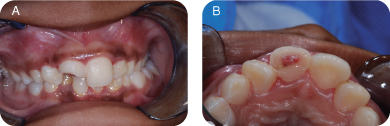

- Traumatized tooth: Maxillary right permanent central incisor—complicated fracture (pulp exposure), class II mobility (Figure 4.3.2)

Figure 4.3.2a–b. Intraoral photos showing maxillary right permanent central incisor—complicated fracture (pulp exposure)

Occlusal Evaluation of Mixed Dentition

- No significant findings

Other

- Poor oral hygiene with extensive plaque accumulation

I. Diagnostic Tools

- Periapical radiograph demonstrates immature apices of maxillary incisors (Figure 4.3.3)

- Percussion tests

- Maxillary permanent lateral incisors: Negative

- Maxillary permanent central incisors: +2

- Vitality tests: Deferred

Figure 4.3.3. Periapical radiograph demonstrating immature apices of maxillary incisors

- Take adequate radiographs that clearly show all involved teeth, including periapices

- Note apical development because it impacts treatment selected (see Flowchart C at end of this chapter) and prognosis. Pulp survival is more likely in luxated teeth with immature apices. Pulp canal obliteration is the most common sequela to luxation injuries to immature permanent teeth

- Rule out other injuries, e.g., root fractures, alveolar fractures

- Vitality tests frequently yield false-negative results for up to three months following an injury

(Flores et al. 2007)

J. Diagnosis and Problem List

Diagnosis

- Maxillary right permanent central incisor: Complicated crown fracture with subluxation

- Optimal care indicates treatment as soon as possible after the injury. Patient behavior, lack of availability of facilities and materials, or management of more serious injuries may delay treatment. Successful outcomes have been reported when treatment of complicated crown fractures is delayed up to several days, so the clinician may elect to defer treatment until the following morning, if necessary, to assure optimal treatment

- The treatment objective is to complete a debridement of inflamed or infected pulp tissue while maintaining healthy pulp tissue. This is particularly important in immature teeth in order for complete root maturation (apexogenesis) to occur

(Cvek 1978, Flores et al. 2007)

K. Comprehensive Treatment

- See Flowchart C at the end of the this chapter

- Maxillary right permanent incisor: Partial pulpotomy (Cvek technique, see Fundamental Point 3)

- Isolate tooth with rubber dam

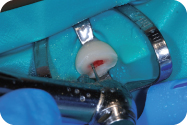

- Gently remove 1.5 to 2 mm of pulp tissue with sterile bur and copious irrigation with water (Figure 4.3.4)

- Use wet cotton pellet to control hemorrhage.

- Cover pulp with calcium hydroxide, followed by glass ionomer

- Assure an excellent seal with composite resin provisional restoration (Figure 4.3.5). Final restoration may be completed at same appointment if it can be done atraumatically. However, final restoration should be deferred if tooth is mobile

- Suture gingival lacerations (if indicated). Prescribe over-the-counter acetaminophen or ibuprofen for pain, as needed

- Only a superficial layer of inflamed pulp tissue is removed, leaving healthy pulp tissue in the coronal chamber and root canal space

- Copious irrigation and a sharp, sterile bur are used to minimize injury to the remaining pulp

- The access preparation is deep enough (1.5 to 2 mm) to contain the wound dressing (CaOH or mineral trioxide aggregate [MTA]) and glass ionomer seal

(Cvek 1978, Flores et al. 2007)

Figure 4.3.4. Partial pulpotomy technique

Figure 4.3.5. Composite resin provisional restoration

Discharge Instructions

- Avoid incising on injured tooth until tenderness resolves

- Instruct parents to watch for clinical signs including tooth discoloration and presence of parulis or fistula

- Instruct child to report increased pain or mobility

Follow-up Treatment

- Two-week post-op visit

- Clinical exam: Assess vitality with cold and electric pulp tests; assess color, mobility, and pain to percussion

- Complete final restoration of tooth if not done at first appointment

- Six-week post-op visit

- Clinical exam: Repeat assessment above

- Radiographic exam: Assess for signs of pulp necrosis, periapical radiolucency, or inflammatory resorption, and for continuing root development

- Repeat same post-op assessments at six months and one year.

L. Prognosis and Discussion

- Prognosis depends on maintaining vitality of the pulp in the maxillary right permanent central incisor. The goal is to achieve full root maturation by removing inflamed pulp tissue while retaining healthy pulp in the root canal and crown. While a direct pulp cap may be simpler and quicker to perform than a partial pulpotomy, the consequences of failure (pulp necrosis) are dire in a tooth with an immature apex. Lacking a vital pulp makes the chances of the tooth achieving complete root maturation markedly decreased. A false/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses