Viral Infections of the Oral Cavity

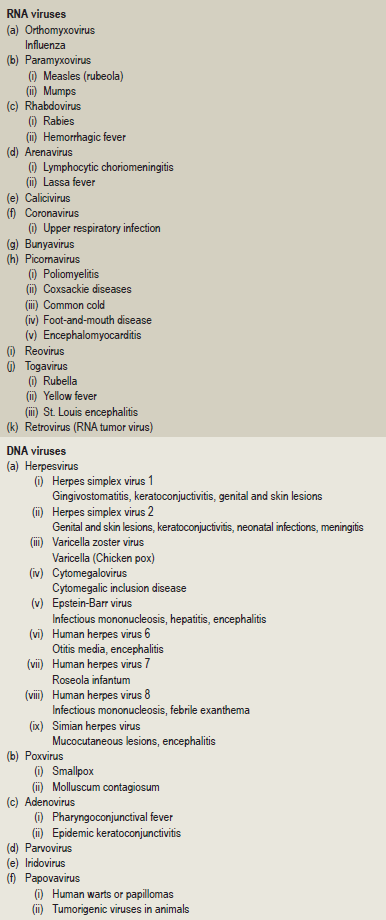

The classification of viral diseases is difficult because of the size of viruses and their incompletely understood metabolic systems. However, their classification based on the biologic, chemical and physical properties of the animal viruses, separating them into groups according to the type of nucleic acid, and the size, shape and substructure of the particle, has been undertaken by the International Committee on Nomenclature of Viruses of the International Association of Microbiological Societies. This classification, with examples of human diseases in the various groups, is shown in Table 6-1.

Herpes Simplex: (Acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, herpes labialis, fever blisters, cold sores)

Pathogenesis

The primary HSV infection is usually acquired through direct contact with affected area or through secretions. The virus once attached to the cells at inoculation site through specific receptors; it replicates too many virions to the maximum number and discharges to neighboring cells. Subsequently it affects adjacent cells, spreads to distant sensory nerve endings and autonomic axons, further to adjacent related ganglia, and remains latent there. The lymph node is involved through viral proteins by mobile dendritic cells and begins its primary immune response. The reason for the wide anatomical distribution and multiple crops may be due to descending spread of virions back to periphery from various neuronal site. Initial or primary infection is asymptomatic and occurs commonly in childhood or infancy. This disease manifests as characteristic vesicles containing desquamated cells, multinucleated giant cells, and free viruses with edema fluid. Though both subtypes produce orofacial and genital lesions, which are clinically indistinguishable, HSV-1 predominantly affects the face, lips, the oral cavity, and upper body skin; and HSV-2 usually affects the genitals and skin of the lower half of the body. Primary infection resolves and the virus can no longer be recovered from ganglia but viral DNA can be found in the ganglion cells. Both humoral and cell mediated immunity is responsible for the clinical manifestation, latency, and recurrence of the disease. Immune-compromised individuals, especially with impaired cellular immunity, are more prone for dissemination and recurrence of the primary disease.

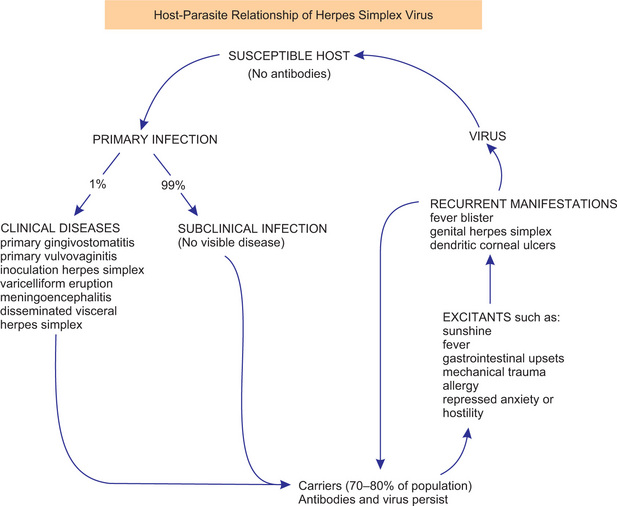

These and other studies have finally led to the established principle that two types of infection with the herpes simplex virus occur. The first is a primary infection in a person who does not have circulating antibodies, and the second is a recurrent infection in persons who have such antibodies. It is impossible to differentiate clinically between the lesions of a primary and a recurrent attack, although the primary infection is accompanied more frequently by severe systemic manifestations and is occasionally fatal. It has been shown; however, that most adults have circulating antibodies in the blood, but have never exhibited a severe primary illness. Thus, it is reasoned, subclinical primary infections must be common. The relation between the primary and secondary forms of the herpes simplex infection is shown in Figure 6-1.

Figure 6-1 Relationship of primary and recurrent herpes simplex. Courtesy of Dr Harvey Blank. From H. Blank and G. Rake: Viral and Rickettsial Diseases of the Skin, Eye and Mucous Membranes of Man. Boston, Little, Brown and Company, 1955.

Herpes genitalis, caused by HSV-2, is a relatively common disease of the uterine cervix, vagina, vulva, and penis. The incidence of this form of the infection has increased precipitously in the United States within the past decade, and in fact, is now often termed the ‘new epidemic venereal disease,’ since it is transmitted through sexual contact. This virus differs immunologically from type 1 herpes virus, which is responsible for most cases of herpetic infection of the oral cavity. The type 2 virus of genital herpes is somewhat more virulent than type 1, and significantly, has been associated repeatedly with carcinoma of the uterine cervix, thus suggesting a possible cause and effect relationship. However, because of changing sexual practices, there has been rather widespread translocation in the usual habitats of type 1 and type 2 HSV. Thus, it is not unusual today to find HSV-2 on the lips or oral mucous membranes and HSV-1 on the genitalia.

Primary Herpetic Stomatitis

Clinical Features

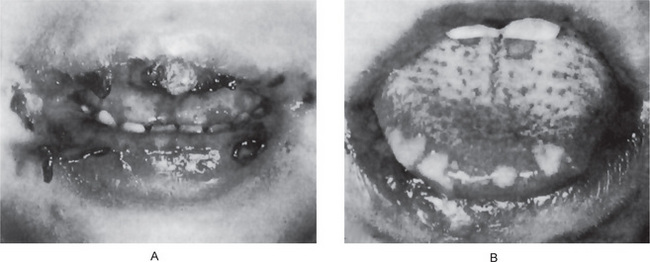

Herpetic stomatitis is a common oral disease transmitted by droplet spread or contact with the lesions. It affects children and young adults. However, it has been suggested by Sheridan and Herrmann that the primary form of the disease is probably more common in older adults than was once thought. It rarely occurs before the age of six months, apparently because of the presence of circulating antibodies in the infant derived from the mother. The disease occurring in children is frequently the primary attack and is characterized by the development of fever, irritability, headache, pain upon swallowing, and regional lymphadenopathy. Within a few days, the mouth becomes painful and the gingiva which is intensely inflamed appears erythematous and edematous. The lips, tongue, buccal mucosa, palate, pharynx, and tonsils may also be involved. Shortly, yellowish, fluid-filled vesicles develop. These vesicles rupture and form shallow, ragged, extremely painful ulcers covered by a gray membrane and surrounded by an erythematous halo (Fig. 6-2). It is important to recognize that the gingival inflammation precedes the formation of the ulcers by several days. The ulcers vary considerably in size, ranging from very tiny lesions to lesions measuring several millimeters or even a centimeter in diameter. They heal spontaneously within 7–14 days and leave no scar.

Figure 6-2 Primary herpetic gingivostomatitis.

The children in both cases exhibited severe involvement of the lips and oral cavity Courtesy of Dr Warren B Davis and Dr John R Mink.

Utilizing culture techniques, August and Nordlund found that the HSV-1 could be isolated from facial, labial, and oral herpetic lesions for a mean duration of three-and-a-half days, with a range of 2–6 days, after the onset of the lesions, while HSV-2 could be isolated from genital lesions for a mean duration of five-and-a-half days, with a range of 2–14 days, after onset. They also noted that viral persistence in lesions did not seem to differ between mild primary infection and recurrent infection. In addition, Turner and his colleagues have shown that HSV could survive for two to four hours on environmental surfaces such as cloth and plastic as well as on the skin of the hands contaminated by direct contact with labial or oral lesions.

Recurrent or Secondary Herpetic Labialis and Stomatitis

The recurrence is related to reactivation of infection and various theories namely (i) ganglionic trigger theory due to nerve section, surgery, or fever (ii) skin trigger theory due to UV light or trauma and (iii) emotional theory due to stress, have been put forward for reactivation. The recurrent form of the disease is often associated with other factors like fatigue, menstruation, pregnancy, upper respiratory tract infection, allergy, or gastrointestinal disturbances. The mechanism through which these various precipitating factors elicit an outbreak of lesions is unknown. The viruses, once introduced into the body, appear to reside dormantly within the regional ganglia, and when reactivation is triggered, spread along the nerves to sites on the oral mucosa and skin where they destroy the epithelial cells and induce the typical inflammatory response with the characteristic lesions of recurrent infection.

Clinical Features

Recurrent herpes simplex infection may occur at widely varying intervals, from nearly every month in some patients to only about once a year or even less in others. The lesions may develop either at the site of primary inoculation or in the adjacent area supplied by the involved ganglion. It may develop on the lips (recurrent herpes labialis, Fig. 6-3) or intraorally (Fig. 6-4). In either location, the lesions are frequently preceded by a burning or tingling sensation and a feeling of tautness, swelling or slight soreness at the location in which the vesicles subsequently develop. These vesicles are generally small (1 mm or less in diameter), tend to occur in localized clusters, and may coalesce to form somewhat larger lesions. These gray or white vesicles rupture quickly, leaving a small red ulceration, sometimes with a slight erythematous halo. On the lips, these ruptured vesicles become covered by a brownish crust. The degree of pain present is quite variable.

Figure 6-3 Recurrent herpetic vesicle of the lip. Courtesy of Dr Ajayprakash P and Dr Susma P, Kamineni Institute of Dental Sciences and Hospitals, Narketpally, Andhra Pradesh.

The lesions gradually heal within 7–10 days and leave no scar.

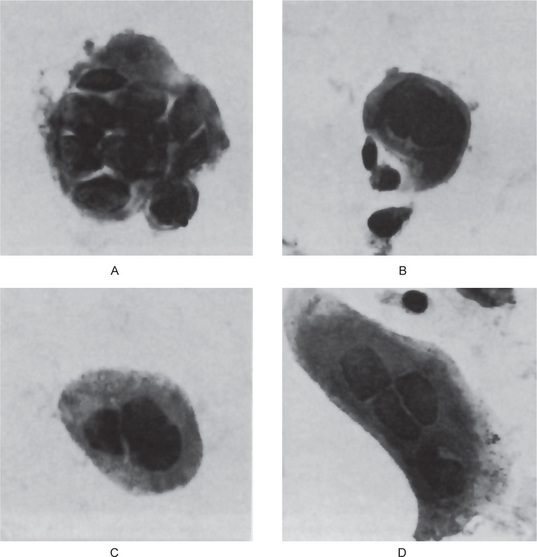

Histologic Features

A number of investigators, beginning with Blank and his associates, have shown that the Papanicolaou smear, using fresh scrapings from the base of a vesicle, is a reliable technique for the diagnosis of active herpes simplex infection if herpes zoster/varicella infection is ruled out, since no other conditions produce a similar cytopathic effect. ‘Ballooning degeneration,’ chromatin margination and typical Lipschütz bodies as described earlier are all seen in smears from these lesions, as well as characteristic multi-nucleated giant cells originally observed by Tzanck (Fig. 6-5). Nowakovsky and her coworkers have thoroughly reviewed the manifestations of viral infections in exfoliated cells. The histologic findings in biopsy specimens from the recurrent lesions are identical to those described under the primary form of the disease.

Laboratory Findings

• Viral isolation and identification in various systems, including eggs, and mice, as well as cell culture technique.

• Immunofluorescent staining of smears, impressions, or cryostat sections with fluorescein-labeled HSV protein or antibody protein.

• Immunoperoxidase technique, which is reportedly far more sensitive than the immunofluorescence technique, is similar in basic principle but does not require fluorescence microscopy.

• Serologic assays such as the complement fixation assay, radioimmunoassay (RIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Differential Diagnosis

A consideration of differential diagnosis is of great importance, since numerous diseases may bear some resemblance to herpes simplex. Thus, some difficulty may be encountered in distinguishing herpes simplex particularly from the recurrent aphthous stomatitis (q.v.). Other conditions to be considered are herpes zoster, impetigo, erythema multiforme, and related diseases, smallpox, pemphigus, epidermolysis bullosa, food or drug allergies, and chemical burns.

Herpangina: (Aphthous pharyngitis, vesicular pharyngitis)

Clinical Features

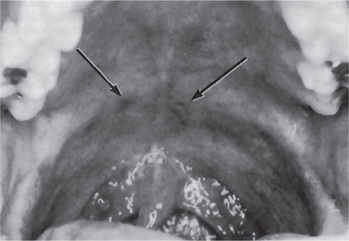

The clinical manifestations of herpangina are comparatively mild and of short duration. It begins with sore throat, cough, rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, headache, sometimes vomiting, prostration, and abdominal pain. The patients soon exhibit small vesicles which rupture to form crops of ulcers, each showing a gray base and an inflamed periphery on the anterior faucial pillars and sometimes on the hard and soft palates, posterior pharyngeal wall, buccal mucosa; and tongue (Fig. 6-6). Vesicles preceding the ulcers are small and of short duration, and are frequently overlooked by the examiner. The ulcers do not tend to be extremely painful, although dysphagia may occur. The systemic symptoms resolve within few days. Ulcers generally heal within 7–10 days.

Laboratory Findings

The Coxsackie virus can be isolated in suckling mice or hamsters by inoculation of scrapings from the throat lesions or stool specimens of nearly all patients who manifest clinical signs and symptoms of the disease or who have had contact with infected patients. Although there are distinct immunologic differences between various strains of herpangina virus, animal inoculation of any type produces the same manifestations—destruction of skeletal muscles followed by death. Even after the disappearance of clinical manifestations of the disease in the human patient, the virus may still be isolated from him/her for one to two months.

Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

Oral Manifestations

The lesions, characteristic of the disease, are raised, discrete, whitish or yellowish to dark pink solid papules or nodules, surrounded by a narrow zone of erythema (Fig. 6-7). The lesions are not vesicular and do not ulcerate. The lesions characteristically appear on the uvula, soft palate, anterior pillars, and posterior oropharynx.

Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease

Clinical Features

The disease is primarily one affecting young children, the majority of cases occurring between the ages of six months and five years. It is characterized by the appearance of maculopapular, exanthematous, and vesicular lesions of the skin, particularly involving the hands, feet, legs, arms, and occasionally the buttocks. The patients commonly manifest anorexia, low-grade fever, coryza and sometimes lymphadenopathy, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting.

Foot-and-Mouth Disease: (Aphthous fever, hoof-and-mouth disease, epizootic stomatitis)

Measles: (Rubeola, red spots, morbilli)

Oral Manifestations

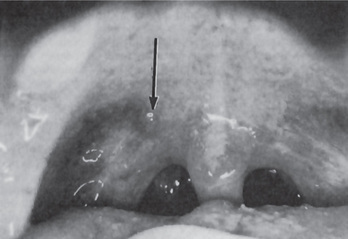

The oral lesions are prodromal, frequently occurring two to three days before the cutaneous rash, and are pathognomonic of this disease. These intraoral lesions are called Koplik’s spots and have been reported to occur in as high as 97% of all patients with measles. The Koplik’s spots are white papules resembling table salt like crystals with red base which appear usually on the buccal mucosa opposite to first and second molar teeth. Immune reaction to the virus in the endothelial cells of dermal capillaries plays a role in the development of spots. The spots disappear after the onset of rash. In actual practice, they are seldom seen unless the affected child has had a known contact with measles and the dentist or parent watches carefully, since the child is often well at the time they appear. These characteristic spots are small, irregularly shaped flecks which appear as bluish, white specks surrounded by a bright red margin. These macular lesions increase in number rapidly and coalesce to form small patches. Palatal and pharyngeal petechiae as well as generalized inflammation, congestion, swelling, and focal ulceration of the gingiva, palate and throat may also occur.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses

. Herpes Simplex

. Herpes Simplex . Herpangina

. Herpangina . Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis

. Acute Lymphonodular Pharyngitis . Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease

. Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease . Foot-and-Mouth Disease

. Foot-and-Mouth Disease . Measles

. Measles . Rubella

. Rubella . Smallpox

. Smallpox . Molluscum Contagiosum

. Molluscum Contagiosum . Condyloma Acuminatum

. Condyloma Acuminatum . Chickenpox

. Chickenpox . Herpes Zoster

. Herpes Zoster . Mumps

. Mumps . Nonspecific ‘Mumps’

. Nonspecific ‘Mumps’ . Cytomegalic Inclusion Disease

. Cytomegalic Inclusion Disease . Poliomyelitis

. Poliomyelitis . Chikungunya

. Chikungunya . Oral Manifestations of HIV Infection

. Oral Manifestations of HIV Infection . Epidemiology

. Epidemiology . Human Immunodeficiency Virus

. Human Immunodeficiency Virus . Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

. Herpes Simplex Virus Infection . Diagnosis of HIV

. Diagnosis of HIV