Red and White Lesions

Description of Red and White Lesions

White Lesion

This normal color of the mucosa may turn into white due to the increased thickness of the epithelium with increased production of keratin (hyperkeratosis) and production of abnormal keratins and imbibition of fluid by the upper layers of the mucosa. In situations like coagulation of tissue surface (occurs in burns), results in the formation of white pseudomembrane, which remains attached to the mucosa but can be scraped off easily. Generally white lesions result from various factors like, trauma, infections, immunologic injury to the mucosa or other genetically determined factors.

Etiologic Classification of Red and White Lesions

Intraoral skin grafts (people of Afro-Asian origin) will not generally exhibit a white coloration of the skin graft. The graft will appear black or brown depending on the extent of melanin pigmentation (Figure 1).

White Lesions of the Oral Cavity

White lesions of the oral cavity can be categorized clinically as keratotic (non-scrapable) or non-keratotic (scrapable) lesions. Table 1 gives a list of scrapable and non-scrapable lesions.

Table 1

Non-scrapable and scrapable lesions

| Keratotic lesions (non-scrapable) | Non-keratotic lesions (scrapable) |

| Linea alba buccalis | Chemical burn/thermal burn |

| Frictional/traumatic keratosis | Pseudomembranous candidiasis |

| Homogeneous leukoplakia | Syphilitic mucous patch |

| Reticular lichen planus | Diphtheritic patch |

| Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis | |

| Dyskeratosis congenita | |

| White sponge nevus |

Frictional Keratosis/Traumatic Keratosis

Linea alba buccalis is a non-scrapable white line that is present on the buccal mucosa usually along the plane of occlusion (Figure 2). It may either be seen unilaterally or bilaterally. Linea alba occurs due to the constant friction or irritation of the buccal mucosa by the facial surfaces of teeth. It is more pronounced with respect to the posterior teeth and may have a scalloped architecture. It is asymptomatic and usually does not require any form of management.

Figure 2 Linea alba on the buccal mucosa. Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

Individuals with chronic cheek biting (morsicatio buccarum) have either a habit of sucking the cheeks frequently or push the cheek in between teeth with their finger. Similarly individuals with chronic lip chewing habit (morsicatio labiorum) and chronic tongue nibbling habit (morsicatio linguarum) present with macerated appearance of the labial mucosa and lateral surface of the tongue respectively. The lower labial mucosa is usually affected in lip chewers (Figure 3A, B).

Figure 3 (A) Whitish macerated appearance of the upper labial mucosa. (B) Whitish thickened and shredded area on the lower labial mucosa. Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

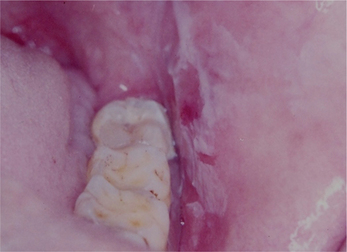

Frictional keratosis is also caused by the rough flange of denture, sharp cusp of a tooth or sharp edge of broken teeth (Figure 4).

Chemical Burns and Thermal Burns

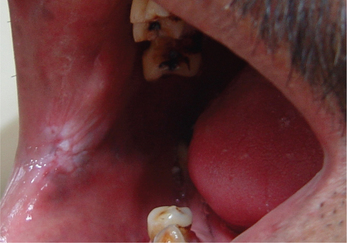

The clinical appearance of these burns in most cases depends upon the severity of the tissue damage. Chronic mild burn usually produces keratotic white lesion whereas intermediate burn causes localized mucositis and the more severe burns coagulates the surface of the tissue and produces a diffuse white lesion. In such cases the tissue can be scraped off, leaving a raw bleeding painful surface (Figure 5).

Figure 5 A chemical burn on the buccal mucosa that is characterized by the presence of a white pseudomembrane that reveals an underlying erythematous area when scraped off. Courtesy: Dr Ashok

Nicotine Stomatitis (Stomatitis Nicotine Palatinus, Smoker’s Palate)

Clinical features

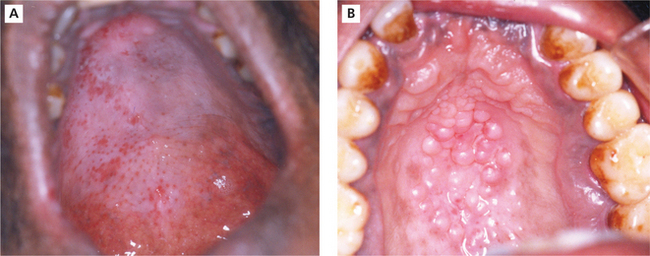

Smoker’s palate is usually seen in males. However, in the Indian subcontinent women who have the habit of reverse chutta smoking also exhibit these mucosal changes. It is generally asymptomatic. The palatal mucosa appears as a diffuse grayish white surface or flat topped nodules may be seen with red pinpoint areas situated in the center of each nodule (Figure 6A, B). These red pinpoint areas correspond to the inflamed orifice of the minor salivary gland ducts.

Leukoplakia

Definition

The requirement for a clear definition for oral white lesions has long been recognized. Similar requirements also apply to red lesions or the red component of preponderantly white lesions. The definition of leukoplakia has often been confusing and controversial. Currently the WHO definition and definition given by Axell are widely used. Auluck et al conducted a survey in 10 different dental colleges in India among 153 specialists including oral surgeons, oral physicians and oral pathologists to check the prevalence of confusion regarding the definition of leukoplakia and its application. It was found that 33.33% of the specialists preferred to follow WHO definition (1978), while 65.35% preferred to follow Axell (1984) definition. The authors described the current ambiguity regarding the accepted definition of oral leukoplakia and emphasized the need for an international collaboration to reach a consensus on the use of the term leukoplakia.

Epidemiology

The frequency of leukoplakia is highly variable among geographical areas and demographic groups. The prevalence in the general population varies from less than 1 to more than 5%. The prevalence of leukoplakia increases to 8% in men over the age of 70 and the prevalence in women past the age of 70 is approximately 2%.

Mehta et al (1961) reported the prevalence of 3.5% in 4,734 Indian population. Manghi et al (1965) reported a prevalence of 6.5% among 2,004 persons. Smith et al (1975) reported a prevalence of 11.7% among 57,518 persons. Yang et al (2001) reported the prevalence of leukoplakia as 24.4% among the aborigines in southern Taiwan. Chang et al (2005) reported the prevalence of 7.44%. In a 10-year follow-up study, a random sample of 30,000 villagers in three areas in India, the annual incidence rates varied from 1.1 to 2.4 per 1,000 men and 0.03 to 1.3 per 1,000 women.

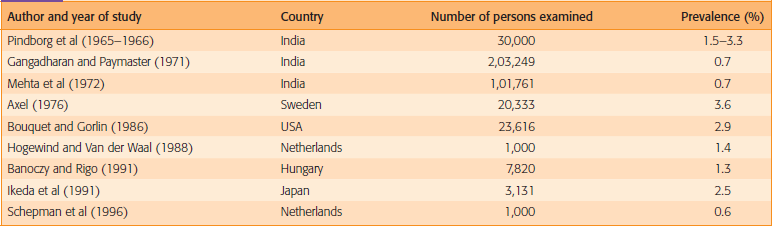

Table 2 gives the overall impression of the prevalence of oral leukoplakia with a geographic emphasis.

Classification and staging system for oral leukoplakia

L1 Size of single or multiple leukoplakia together < 2 cm

L2 Size of single or multiple leukoplakias together 2–4 cm

P0 No epithelial dysplasia (includes ‘no or perhaps mild epithelial dysplasia’)

P1 Distinct epithelial dysplasia (includes ‘mild to moderate’ and ‘moderate to possibly severe’ epithelial dysplasia)

Px Absence or presence of epithelial dysplasia not specified in the pathology report.

OLEP (Oral leukoplakia) staging system

| Stage I | L1P0 |

| Stage II | L2P0 |

| Stage III | L3P0 or L1L2P1 |

| Stage IV | L3P1 |

General guidelines for oral leukoplakia staging system

1. If there is doubt concerning the correct L or P category to which a particular case should be allotted, then the lower (i.e. less advanced) category should be chosen. This will also be reflected in the stage grouping.

2. In case of multiple biopsies of single leukoplakia or biopsies taken from multiple leukoplakias the highest pathological score of the various biopsies should be used.

3. For reporting purposes the oral subsite according to the ICD-DA should be mentioned.

Etiopathogenesis

1 Tobacco (smoke/smokeless form)

Use of tobacco in the form of factory-made cigarettes, beedi, cigars and cheroots and powdered tobacco in pipes or rolled into hand-made cigarettes, are the main etiological agents in the causation of leukoplakia.

4 Leukoplakia and diabetes

Albert et al (1992) reported an OL prevalence of 6.2% among diabetics as compared to 2.2% in a control group. However the analysis did not adjust for age and gender. Diabetes mellitus leads to a number of metabolic and immunologic changes that affect the oral mucosa and it is associated with a variety of oral conditions (Ponte et al, 2001). Thomas et al (2004) have found a significant association between diabetes mellitus and OL prevalence.

Clinical features

1. Leukoplakia is seen most frequently in middle-aged and older individuals. Sex distribution is also variable. Men are more affected in some countries, while this is not the case in the western world. Less than 1% of men below the age of 30 have leukoplakia. The male-to-female ratio is reported to be about 3:1 to 6:1.

2. Leukoplakia can be either solitary or multiple.

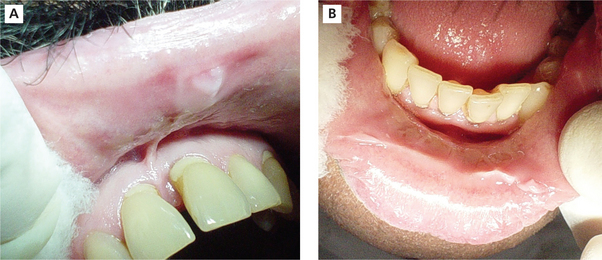

3. Leukoplakia may appear on any site of the oral cavity, the most common sites being: buccal mucosa, alveolar mucosa, floor of the mouth, lateral border of tongue, lips and palate, however the lesions in the floor of the mouth, lateral border of the tongue and lower lip are most likely to show dysplastic or malignant changes. By far the most affected oral sites are the commissures (Figure 7) and the buccal mucosa (Figure 8) showing 60–90% of the leukoplakia. Next are the lip (3.7%), the alveolar ridge (3.0%) (Figure 9), the tongue (1.4%), floor of the mouth (1.3%), vestibular mucosa (1.1%) (Figure 10) and the palate (0.9%).

Figure 7 Commissural leukoplakia. Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

Figure 10 Keratotic white patch in the labial vestibule due to placement of tobacco (tobacco pouch keratosis). Courtesy: Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, MCODS, Mangalore

4. Early or thin leukoplakia appears as a slightly elevated grayish-white plaque that may be either well defined or may gradually blend into the surrounding normal mucosa (Figure 11). As the lesion progresses, it becomes thicker and whiter, sometimes developing a leathery appearance with surface fissures. Some leukoplakias develop surface irregularities and are referred to as granular or nodular leukoplakias. Other lesions develop a papillary surface and are known as verrucous or verruciform leukoplakia.

Clinical forms of leukoplakia

Homogeneous leukoplakia is defined as a predominantly white lesion of uniform flat and thin appearance that may exhibit shallow cracks and that has a smooth, wrinkled or corrugated surface with a consistent texture throughout (Figure 12). This type is usually asymptomatic.

Non-homogeneous leukoplakia has been defined as a predominant white or white-and-red lesion (erythroleukoplakia) (Figure 13) that may be either irregularly flat, nodular (speckled leukoplakia) or exophytic (exophytic or verrucous leukoplakia). These types of leukoplakia are often associated with mild complaints of localized pain or discomfort. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia is an aggressive type of leukoplakia that almost invariably develops into malignancy. This type is characterized by widespread and multifocal appearance, often in patients without known risk factors. In general, non-homogeneous leukoplakia has a higher malignant transformation risk, but oral carcinoma can develop from any leukoplakia.

Malignant transformation

White lesion in the oral cavity were thought to be precancerous as early as 1870 by Paget, who gave them such appellations as ichthyosis, smoker’s patch and leukokeratosis.

Investigations

Toluidine blue staining: Toluidine blue clinically stains malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa. In vivo, the dye may be taken up by the nuclei of malignant cells manifesting increased DNA synthesis. Toluidine blue also serves as a guide to biopsy by localizing tumor cells within the area of the lesion. Toluidine bluestaining uses a 1% aqueous solution of the dye that is decolorized with 1% acetic acid. The dye binds to dysplastic and malignant epithelial cells with a high degree of accuracy (Figure 14).

Toluidine blue staining: Toluidine blue clinically stains malignant lesions, but not normal mucosa. In vivo, the dye may be taken up by the nuclei of malignant cells manifesting increased DNA synthesis. Toluidine blue also serves as a guide to biopsy by localizing tumor cells within the area of the lesion. Toluidine bluestaining uses a 1% aqueous solution of the dye that is decolorized with 1% acetic acid. The dye binds to dysplastic and malignant epithelial cells with a high degree of accuracy (Figure 14).

Figure 14 Toluidine blue stained leukoplakic lesion on the gingiva and buccal vestibule. Courtesy: Dr Ashok

Cytobrush technique: This technique is more accurate than any other cytologic technique used in the oral cavity. The cytobrush technique uses a brush with firm bristles that obtains individual cells from the full thickness of the epithelium.

Cytobrush technique: This technique is more accurate than any other cytologic technique used in the oral cavity. The cytobrush technique uses a brush with firm bristles that obtains individual cells from the full thickness of the epithelium.

These two techniques are adjuncts and not substitutes for an incisional biopsy.

Biopsy: When a suspicious lesion is identified, an incisional biopsy using a scalpel or a biopsy forceps is recommended. When the lesion is very small excisional biopsy is performed as an investigative procedure and as a treatment modality.

Biopsy: When a suspicious lesion is identified, an incisional biopsy using a scalpel or a biopsy forceps is recommended. When the lesion is very small excisional biopsy is performed as an investigative procedure and as a treatment modality.

In homogeneous leukoplakia, the value of histological examination to some extent is questioned. The occurrence of epithelial dysplasia is rather low in this type as is the risk of future malignant transformation. However, even the experienced clinician will occasionally be surprised by the histopathological findings of a clinically innocent looking homogeneous leukoplakia. Therefore a biopsy should be performed in homogeneous leukoplakia. In non-homogeneous leukoplakia, i.e. usually symptomatic, epithelial dysplasia or even carcinoma in situ or early squamous cell carcinoma is rather common. The biopsy should be taken at the site of symptoms, if present, and or a site of redness or induration. Biopsies of exophytic, verrucous or papillary lesions should be taken deep enough to include a sufficient amount of underlying connective tissue, and preferably from the margins.

In homogeneous leukoplakia, the value of histological examination to some extent is questioned. The occurrence of epithelial dysplasia is rather low in this type as is the risk of future malignant transformation. However, even the experienced clinician will occasionally be surprised by the histopathological findings of a clinically innocent looking homogeneous leukoplakia. Therefore a biopsy should be performed in homogeneous leukoplakia. In non-homogeneous leukoplakia, i.e. usually symptomatic, epithelial dysplasia or even carcinoma in situ or early squamous cell carcinoma is rather common. The biopsy should be taken at the site of symptoms, if present, and or a site of redness or induration. Biopsies of exophytic, verrucous or papillary lesions should be taken deep enough to include a sufficient amount of underlying connective tissue, and preferably from the margins.

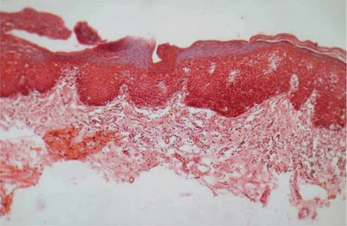

This lesion represents various degrees of epithelial dysplasias. Some lesions exhibit carcinoma in situ with top to bottom basilar hyperplasia, loss of polarity, increased mitosis, hyperchromatism, dyskaryosis and alteration in nuclear cytoplasmic ratio without any evidence of thickening of epithelial layer or without any evidence of disturbance of keratinization process (Figure 15).

This lesion represents various degrees of epithelial dysplasias. Some lesions exhibit carcinoma in situ with top to bottom basilar hyperplasia, loss of polarity, increased mitosis, hyperchromatism, dyskaryosis and alteration in nuclear cytoplasmic ratio without any evidence of thickening of epithelial layer or without any evidence of disturbance of keratinization process (Figure 15).

Figure 15 Hyperorthokeratosis and basal cell hyperplasia in leukoplakia. Courtesy: Department of Oral Pathology, MCODS, Mangalore

The frequency of epithelial dysplasia in leukoplakia varies between less than 1% and more than 30%. The presence of epithelial dysplasia is generally accepted as one of the most important predictors of malignant development in premalignant lesions.

The frequency of epithelial dysplasia in leukoplakia varies between less than 1% and more than 30%. The presence of epithelial dysplasia is generally accepted as one of the most important predictors of malignant development in premalignant lesions.

Markers of proliferation in leukoplakia: There are markers for determining future cancer development in oral premalignant lesions. These markers are divided into genomic markers and differentiation markers. The genomic markers include DNA aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity and changes in expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (p53), whereas the proliferative markers include keratins and carbohydrate antigens.

Markers of proliferation in leukoplakia: There are markers for determining future cancer development in oral premalignant lesions. These markers are divided into genomic markers and differentiation markers. The genomic markers include DNA aneuploidy, loss of heterozygosity and changes in expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes (p53), whereas the proliferative markers include keratins and carbohydrate antigens.

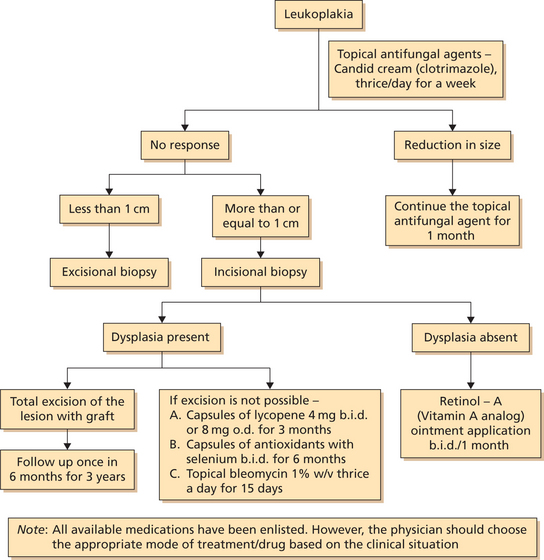

Treatment (Flowchart 1)

General considerations

As a standard rule all possible agents leading to white keratotic lesions should be eliminated such as sharp teeth, candidal infection, etc. so as to rule out other definable lesions. In persisting lesions or in the absence of possible causative factors, a biopsy should be taken to exclude histologically the presence of a definable lesion and to establish the degree of epithelial dysplasia, if present or even the presence of carcinoma or carcinoma in situ.

1 Carotinoids and retinoids

(β-carotine, Vitamin E, selenium, canthaxanthin, astaxanthin, phytoene and spirulina-dunaliella)

Beta-carotene is a natural precursor of vitamin A. More recently etretinate 13-cis retinoic acid and other retinoid have been successfully used for the treatment of oral leukoplakia. Exactly how retinoids may act to inhibit carcinogenesis is unclear, although some retinoids may enhance anti-tumor immune responses. Retinoids have a pronounced and essential effect on cell differentiation. Retinoids may have an effect by their interaction with growth control mechanisms such as transforming growth factors and also possibly by acting on tumor suppressors either directly or via an interaction with transforming growth factors. Retinoids may inhibit the transformation mediated by papillomaviruses. Oral leukoplakias have been treated with a range of retinoids and carotinoids. Leukoplakias have been successfully treated with systemic 13-cis retinoic acid.

Gene therapy

Even though laboratory and animal data for the use of gene therapy is very incomplete, many investigators have begun clinical trials in human patients. Tests of several types of gene therapy have begun in various types of cancer, and for oral cancer; the trials include the testing of recombinant p53, the expression of suicide genes and the use of conditionally competent adenoviruses. Since the scientific basis for these trials is rather weak, it can hardly be expected that impressive results are imminent. There are as yet no trials in oral potentially malignant lesions aimed at correcting genetic changes or enhancing the immune response by gene therapy; indeed the whole field of gene therapy has been publicly criticized for its rush to clinical experiments, when the basic studies are still incomplete.

Green tea

Tea polyphenols are effective in reducing the accumulation of free radicals by inducing the production of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a free radical scavenger (Das et al, 2002).

Tea polyphenols are effective in reducing the accumulation of free radicals by inducing the production of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a free radical scavenger (Das et al, 2002).

Tea inhibits formation of mutagens in a dose dependaet manner (Weisburger et al, 2002) and reduces lipid peroxidation (Fadhel et al, 2002).

Tea inhibits formation of mutagens in a dose dependaet manner (Weisburger et al, 2002) and reduces lipid peroxidation (Fadhel et al, 2002).

In UV induced responses, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) prevents the formation of UVB induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (Katiyar et al, 1999).

In UV induced responses, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) prevents the formation of UVB induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (Katiyar et al, 1999).

EGCG is also a strong inducer of the detoxifying enzyme glutathione-s-transferase.

EGCG is also a strong inducer of the detoxifying enzyme glutathione-s-transferase.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses