CHAPTER 6

Diagnosis of Orthodontic Problems

Carolus Linnaeus (1707-78), Swedish botanist and taxonomist, is considered to be the founder of the binomial system of nomenclature and the originator of modern scientific classification of plants and animals. To paraphrase a quote attributed to him: “Without classification there is only chaos.”< ?xml:namespace prefix = "mbp" />

Before Edward Hartley Angle devised his scheme of classification of malocclusion, there was no reliable or simple method to describe a malocclusion.

The second law of thermodynamics (law of entropy) was formulated in the middle of the nineteenth century by the earlier observations of Carnot and later by Clausius and Thomson.

On a daily basis, we are all faced with patients who seek treatment for the correction of particular problems, some of which are relatively simple and some of which are rather complex. Certainly, the patients’ reasons for seeking our help are multivariant. Nevertheless, no matter the reason, we are obliged to assess their problem, answer their questions, and provide them with information pertinent to their chief complaint. Thus, we perform a thorough diagnosis, create a list of problems, discuss treatment options, and then establish a treatment modality to achieve the goal. The sequencing of the previous sentence is logical and purposeful in its design. After all, it would make little sense to reverse its order and state it this way: “We achieve the goal, we treat the problem, we create treatment options, we set treatment objectives, and we diagnose.”

Orthodontics is both art and science. By its very nature, there is more than one roadmap to a successful treatment for any particular problem, and each orthodontist may have a different approach. In the end, however, each of us must formulate that treatment based upon a sound diagnosis. Orthodontists, like physicians, develop what is frequently referred to as the differential diagnosis. What does this mean, and why is it different than the medical diagnosis? In medicine, a patient presents with certain symptoms. The physician, after interviewing the patient and making a preliminary examination, develops a hypothesis of what he thinks the problem is and develops a differential diagnosis, which is nothing more than a list of possible causes for the patient’s complaint. Not until he performs a variety of tests is he able to narrow the list down and arrive at “the” single most likely definitive diagnosis (e.g., appendicitis). In orthodontics, however, the differential diagnosis represents a somewhat different concept. It is, in fact, a complete description of the malocclusion; it includes those multifactorial conditions that exist at a particular moment in time that make the malocclusion unique unto itself. In other words, we do not simply describe a malocclusion as Class II. Rather, we add to that basic Angle classification a description of all the salient entities that make the malocclusion different from others of the same classification, e.g., division 1, division 2, subdivision, crowding, deep bite, crossbite.

In this chapter the questions ask about the treatment of a particular malocclusion. Suggested treatment approaches are described in the answers and are meant to associate the treatment decision to an understanding of the underlying problem based upon a proper diagnosis. Because there are many ways to correct a particular problem, these suggested treatments are for illustrative purposes only. It is important to note that treatment (mechanotherapy) and diagnosis are entities that are joined at the hip and cannot be separated. A poor treatment result will most certainly result from a poor diagnosis.

As orthodontists, we acknowledge and understand that we treat in three planes of space: the sagittal, the vertical, and the transverse. Although these three dimensions can be thought of as three separate entities, they are not. Why? Treating one will most certainly have a separate or collective effect upon each of the others, either in a positive or a negative way. Therefore, having a complete understanding of all of them and how they interrelate and interact is important when formulating the treatment.

Let us consider, for example, the vertical dimension. The vertical dimension dictates many of the decisions made by the orthodontist when devising a treatment plan. In the case of a patient with a dolichofacial pattern, the comprehensive treatment goal often includes a plan to control the vertical dimension and to not make it worse.

DIAGNOSTIC DATABASE

1 What comprises the diagnostic database?

The diagnostic database is composed of multiple clinical, functional, and record analyses that allow the clinician to formulate a comprehensive diagnosis and begin to work toward a treatment plan that is most beneficial to the patient.

CASE HISTORY

A thorough case history including family and patient history helps establish any pre-existing developmental problems. Medical conditions relating to orthodontic treatment and psychological aspects of treatment should be explored.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

The most important diagnostic tool is the clinical examination of the patient. The general state of the patient in terms of growth and development should be assessed, along with the development and health of the dentition and surrounding structures. A frontal and profile analysis should be performed to discover any discrepancies that would fall into the problem list. The patient’s chief complaint should be noted and evaluated.

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS

In the functional analysis, head posture and freeway space are evaluated. The dentition is evaluated for any discrepancies in function, such as functional shifts or pseudo-bites. Swallowing function should be explored to discover tongue-thrust habits that may lead to relapse after orthodontic treatment is completed. The temporomandibular joints (TMJs) are palpated and the patient is questioned concerning joint function and noise. Any discrepancies from normal should be further evaluated through clinical and radiographic examination as needed.

RADIOLOGIC EXAMINATION

Panoramic radiographs are useful in orthodontic diagnosis as a survey of the total dentition, the TMJs, and surrounding structures. Periapical radiographs or vertical bitewings should be taken on all adult cases to evaluate bone heights. Occlusal views or a cone beam scan may be beneficial in cases with impacted teeth to determine their three-dimensional (3D) location.

PHOTOGRAPHIC ANALYSIS

Profile and frontal photographs are taken to evaluate the relationship between the soft-tissue and the skeletal supporting structures. In the profile view, the patient’s head is parallel to the Frankfort horizontal plane in the natural head position, the eyes are focused straight ahead, and the ear is visible.

CEPHALOMETRIC ANALYSIS

Cephalometric analysis is used to evaluate the formation of the facial skeleton, the relationship of the jaw bases, the axial inclination of the incisors, soft-tissue morphology, growth patterns, localization of malocclusion, and treatment limitations.

STUDY CAST ANALYSIS

The dentition and degree of malocclusion can be analyzed in three dimensions using study cast analysis. Analysis of the arch form can be subdivided into the sum of upper incisor widths, anterior arch width, posterior arch width, anterior arch length, and palatal height. Arch symmetry is evaluated using a perpendicular to the mid-palatal raphe. Space analysis is calculated by subtracting the total amount of tooth structure—or predicted tooth structure if the patient is in the mixed dentition—from the total space available. Incisor inclination, sagittal discrepancies, and depth of the curve of Spee may also influence the space available. Bolton analysis, a ratio of mandibular teeth width sum to maxillary teeth width sum, gives an index to determine how teeth will couple. The overall calculated ratio should be 91%; if the ratio is reduced, the maxillary teeth are relatively too large. The anterior ratio should be 77%. Finally, the occlusion can be studied and classification of the malocclusion can be made and overjet and overbite relationships determined.

2 What is a prioritized problem list?

A prioritized problem list places the orthodontic/developmental problems into priority order to help evaluate the interaction, compromise, and cost/benefit of treatment for each of the problems in order to determine the appropriate course of action that maximizes benefit to the patient.

3 What are the orthodontic problems in the 3 planes of space?

ANTEROPOSTERIOR PLANE

The anteroposterior (AP) plane passes through the body parallel to the sagittal suture, dividing the head and neck into left and right portions. The AP or sagittal dimension deals with maxillary and mandibular forward growth.

TRANSVERSE PLANE

The transverse plane passes horizontally through the body, at right angles to the sagittal and vertical planes, dividing the body into upper and lower portions. The transverse dimension is evaluated skeletally by measuring the width of the posterior maxilla. Measurements less than 36 mm from the upper first molar mesiolingual gingival margins may indicate a skeletal discrepancy.

VERTICAL PLANE

The vertical plane passes longitudinally through the body from side to side, dividing the head and neck into front and back parts. Skeletal discrepancies in the vertical dimension may be determined by analysis of a lateral cephalometric radiograph in coordination with a clinical examination. Discrepancies can include increased or decreased facial height, extremely low or high mandibular plane angle (MPA), or skeletal open bite.

MIDLINES

When evaluating the midline of a patient, it is important to consider both the facial and dental midlines. An evaluation should be made to determine if the dental midlines are coincident with the facial midline and whether they are coincident with one another.

LIPS

The lip posture should be evaluated both at rest and with the lips lightly touching. Watch for evidence of lip strain on closure, which may indicate a need for extraction treatment. Evaluate the upper lip length and the amount of tooth and gum display at rest and on full smile. If no amount of tooth is displayed at rest, the teeth may be dried, utility wax placed at the incisal edges, and the lip length indexed on the wax. The amount of vertical deficiency can then be read from the wax. Excessive gingival display on smiling can be due to short upper lip length, short clinical crowns from excess gum tissue, or vertical maxillary excess. In females, 3–4 mm of incisal display should be present at rest; at full smile, the upper lip should reach the height of the centrals or slightly above.

BUCCAL CORRIDORS

Dark buccal corridor spaces can be due to lingually set or lingually tipped premolars. Indiscriminate expansion has questionable long-term stability and can create buccal root dehiscences.

SMILE LINE

The relationship of the upper teeth to the lower lip should be evaluated for parallelism among their curvatures. Treatment should be aimed at keeping or creating parallelism and avoiding a flat or reverse smile line.

ANTEROPOSTERIOR

The relationship of the maxilla and the mandible to the overall face is evaluated. Deviations in midface projection and mandibular projection are noted.

NOSE

The nose plays an important part in facial balance. Note any morphological variations in shape and discuss any concerns with the patient. Upturned nasal tips tend to be more youthful in appearance but may require variations in treatment planning if extractions are being considered to eliminate crowding in the dentition.

LIPS

The lip posture should again be considered at rest and with lips lightly touching. The interlabial gap should be approximately 1–3 mm at rest posture. Evaluate the amount of incisor display at rest, as well as the inclination of the incisors in relation to facial balance. The nasolabial angle is an indication of upper lip inclination. The E-line proposed by Ricketts is influenced by the nose and chin but can aid in evaluating lip protrusion or retrusion.

VERTICAL

The height of the lower face, from subnasale to menton, can be further subdivided. One third of the distance is measured from subnasale to stomion and two thirds of the distance is measured from stomion to menton. Deviations from this ratio may indicate vertical maxillary excess, a short upper lip, a skeletal open bite, or an increase in anterior facial height. The normal ratio of the lower facial height to the posterior facial height is 0.69.

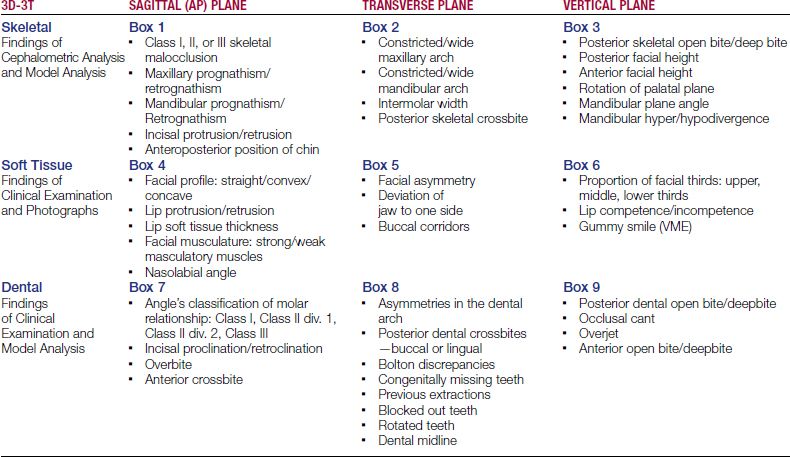

6 What is the 3D-3T diagnostic grid, and why is it important as a routine part of an orthodontic patient record?

The 3D-3T diagnostic grid represents a diagnostic summary of the findings in the three tissue categories: skeletal, soft tissue, and dental for the sagittal, transverse, and vertical planes of space (

7 What are the advantages of using the 3D-3T diagnostic grid in treatment planning?

Listing the examination and orthodontic analyses data in this format ensures that all factors and possibilities for a given case are considered before a treatment plan is established. Each box is designated for a specific problem type; thus, completion of the table ensures that all diagnostic records are carefully considered. In addition, the side effects of correcting one problem, which may help or worsen another problem, are more clearly evaluated before a list of objectives and the best possible treatment plan is selected. The immediate insight into the difficulty of a case is another advantage of this methodology. Understandably, cases with abnormalities involving all tissue categories or all three planes of space require more attention than a case having fewer dimensional problems. A malocclusion with problems in all three places of skeletal tissue will be very difficult to treat. The end result of such an approach is a comprehensive and effective treatment plan with concise and realistic goals.

9 What information is contained within each box?

10 What are treatment objectives?

After the review of all diagnostic findings and the formation of a problem list, the clinician forms a list of goals and treatment objectives listed in order of importance for each patient.

Ideally one would like to correct all existing malocclusions, and in many cases, this can be achieved without difficulty. However, there will be cases in which one or more limiting factors will force the clinician to limit the goals to those most beneficial to the patient. For example, when the patient is a non-grower, the complete correction of a skeletal Class II malocclusion is likely only with the assistance of orthognathic surgery. If the patient is opposed to correctional surgery, the only other realistic alternative, aside from no treatment, is an orthodontic treatment plan designed to camouflage the problem. When Class I molar correction is unlikely, a better aim may be to get the cuspids into a Class I relationship. In cases of upper premolar extractions (without extraction in the lower arch), the cuspids are positioned into a Class I relationship while the molars are kept at a full step Class II position. However, to establish an ideal occlusion, the normal molar 14-degree rotation must be corrected to 0 degrees if in a Class II molar relationship.

Although the treatment goals are made before the treatment plan is created, sometimes they are modified during the process of treatment planning.

11 How does one form a treatment plan?

To form a treatment plan, one takes the treatment objective and then chooses a treatment modality that will achieve that desired result.

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses