Ergonomics

By David J. Ahearn, D.D.S.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate and prioritize the two types of ergonomic improvements involved in a design project, internal and external

• Clarify the role of the office layout and its relationship to operatory workflow and internal ergonomic performance

• Discuss the important components of lean manufacturing principles which positively impact office ergonomics by eliminating wasted effort, simplifying systems and reducing cost in your office design

• Understand the three essential elements of internal ergonomics: proximity, posture, and visibility

With all the details of creating a new office, it is possible to overlook what is ultimately the most critical element of a practice: the dentist. Stated simply, you can’t break the machine that makes it all happen. All of the components of a great practice are of little value if the practitioner becomes unable to practice or cannot practice effectively due to trauma.

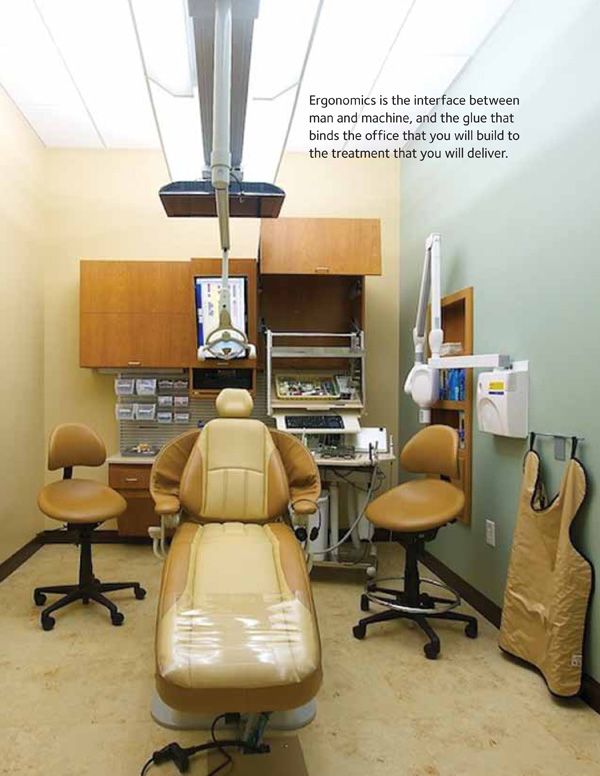

Ergonomics is the interface between man and machine, and the glue that binds the office that you will build to the treatment that you will deliver. Ergonomics in dentistry is an extremely broad field encompassing everything from neuromuscular goniometry, by which we study stress on our bodies, to the principles of lean manufacturing, which seek to reduce the work involved in any manufacturing process. There are two types of ergonomics: “external” ergonomics relate to workflow principles and process simplification, and “internal” ergonomics deal with the reduction of fatigue, stress and injury through the appropriate orientation of the operative environment. We will touch on both types in this chapter as they relate to dental office layout and design.

Great Ergonomics Make You Faster, Not Slower

Some dentists erroneously believe that proper ergonomics will slow down their ability to treat patients. We may learn habits very early in our practice life that we may later wish to alter. Other habits that form early may be unproductive or downright destructive. These habits tend to be reinforced as the practice continues and efforts are made to “improve” performance because by this time, these are learned behaviors. Unfortunately, bad habits are hard to break and good habits don’t feel comfortable as they are being learned.

I strongly suggest that a practitioner learn new techniques for proper visualization at the earliest possible stage, preferably prior to designing and building a new practice. Unfortunately, the multiple demands of an undergraduate dental education may not permit adequate time and attention to the study of ergonomic science. Further, the speed and complexity of private practice far exceeds that of any teaching environment, and many practice situations require us to adopt a very different type of dental delivery than that taught in dental school (Figure 6.1). As a result, less than ideal design decisions regarding workflow, deployment, equipping costs, etc. become built into many practices. Many of these practitioners as they progress in years suffer back, neck, shoulder and wrist pain or injury that might have been entirely avoided through proper workplace design and use.

FIGURE 6.1

Bad habits can develop early in practice life. Many dental students report some level of back, neck or shoulder pain prior to graduation.

You Can’t Use What You Can’t Reach

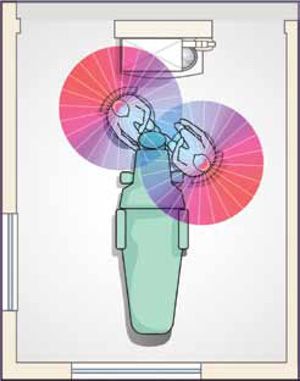

There are many opinions regarding proper operatory layout. However, one central principle that is not subject to opinion is that dental equipment and supplies that are outside the primary range of motion for both operator and the assistant can create an inherent disadvantage from both a performance and an ergonomic standpoint (Figure 6.2). An operatory layout that does not adhere to this central principle can subject the practice to compromises that can have long range effects on the practice. In addition patient size and health variations can require practitioners to be able to respond with a range of postures in order to be able to deliver care to all patients. Therefore, one of the goals of your operatory design should be to increase the flexibility of successful care from a variety of treatment positions rather than to create a treatment environment that locks doctors and staff members into a constricted delivery range of function.

FIGURE 6.2

The area of active, ergonomically acceptable, treatment area (see blue) is actually quite limited.

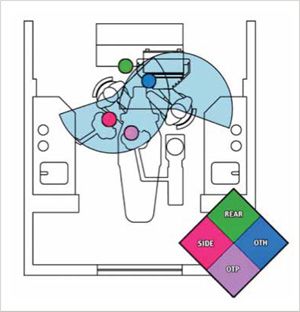

Unfortunately, dentists often get confused between two rather significant decisions regarding how the operatory is to be equipped. The first is from where the handpieces are delivered and the second is where the overwhelming majority of the supplies reside. Of these two decisions, the most important relates to supply placement rather than handpiece placement (Figure 6.3). This is due to the fact that actual handpiece use comprises less than 10% of a typical procedure time.

What has happened over the prior decades is that as supply complexity increased due to the evolving diversity of procedures and materials used, many treatment rooms became increasingly cluttered by storage of excess materials, which can render the operatory more of a warehouse than a location for providing care. This can restrict practitioner range of motion, obstruct the introduction of advanced technology and increase room construction costs.

FIGURE 6.3

There are 4 major variants for handpiece placement. Over-the-head and over-the-patient have the fewest ergonomic and productivity challenges.

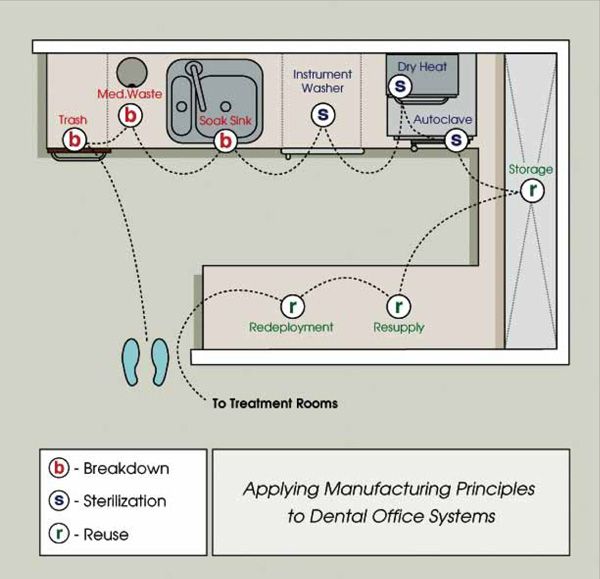

Sterilization should be tightly linked to resupply and redeployment rather than treated as a process in isolation.

FIGURE 6.5

Judicious use of cabinetry in the operatory results in a combination of high treatment efficiency, compact and economical room configuration and multi-functional use.

Office Layout and its Influence on Workflow

One of the primary reasons why excellence in office design is so closely linked to practice success is that a great office design streamlines workflow. Improved workflow reduces the effort required to complete the myriad of tasks involved in successfully servicing a patient from the initial phone call, right up to the completed restoration. Therefore, workflow is a very significant aspect of the office ergonomic improvement effort. There are immeasurable aspects and details of the office architectural design that will affect workflow. Here we will discuss three examples in an effort to illustrate the principles of workflow effectiveness.

One of the primary reasons why excellence in office design is so/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses