Restorative management of dental implants

Chapter Contents

Overview

Assisting patients to attain a healthy, functional and aesthetic dentition is one of the primary goals of any dental practitioner. Unfortunately, there are many reasons why this goal might not be achieved and there is then a requirement for intervention to repair or replace what is damaged or lost over time. Osseointegrated dental implants have been developed over 40 years and now provide a further option for rehabilitating the compromised dentition. This chapter deals with the restorative aspects of dental implants and provides an intentionally basic overview of the restorative and basic surgical elements of rehabilitating patients using implant-retained prostheses.

After an introduction to basic terminology, the chapter is organised to follow a patient’s pathway through presurgical planning, implant placement, immediate restoration and the definitive restoration and maintenance phases of management. The use of dental implants for both single and multiple tooth restorations is described.

5.1 Basic implant terminology

A basic understanding of implant treatment is dependent upon knowledge of the underlying structure of the osseointegrated dental implant system. Dental implant technology is growing rapidly with established systems undergoing continuous development and new systems being introduced to the market on almost a daily basis. It is not the intention here to provide a detailed review of the subtle differences between systems, but to provide an understanding of the underlying principles of dental implants.

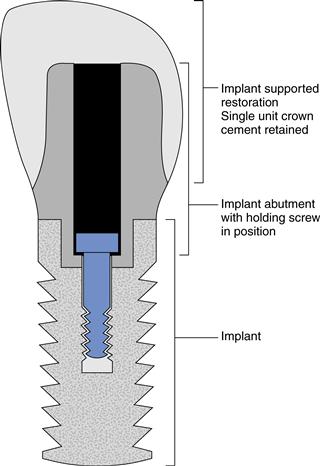

A basic implant system may be considered structurally as comprising three distinct parts: a part that interfaces with the hard tissues; a part which interfaces with the soft tissues; and a part that interfaces with the oral environment. These different structural parts may take the form of either one, two or three separate components. Figure 5.1 shows three separate components diagrammatically and how they are associated with one another. The component that is osseointegrated with bone is usually referred to as the implant and provides retention and support for the prosthesis to bone. The abutment is the component that is connected to the implant and traverses the overlying soft tissue to provide a connection between the implant and the overlying restoration. The final component of the system is the restoration or superstructure that gains support and retention from the implant through the abutment. Although this is a basic overview of the generic implant system, it may be applied to many products whether they comprise separate implants, abutments and restorations or hybrid components (e.g. implant and abutment as a single, joined component).

Implants

Osseointegrated implants are available in a vast array of sizes, shapes, surfaces and linking mechanisms. In all cases, the primary aim of the implant is to integrate with the host’s bone and provide stability and retention for the restoration. Primary stability of the implant is usually provided by some form of mechanical feature (e.g. a self-threading mechanical attachment to the bone when the implant is first placed). The long-term stability and retention of the implant is then dependent upon establishment of biological osseointegration with the host not rejecting what is, in essence, a foreign body placed within the living tissues. Successful osseointegration is indicated by a stable implant that gives a bright note when percussed. Failure is apparent when the implant becomes mobile and may eventually be exfoliated, if infection of the site has not already ensued.

Abutments

Abutments link the implant to restorations in the mouth and maintain a permanent ‘defect’ through the epithelial barrier of the soft tissues. They provide support and retention for the overlying restoration through either an unbreakable physical link (e.g. a cemented single crown) or a breakable physical link (e.g. a magnetically retained complete overdenture).

Implant-supported restorations

Implant-supported restorations serve to replace the tissues which have been lost and it is convenient to consider these as either dental or supporting tissues. A further way to classify restorations is according to whether they are fixed (i.e. cemented, or screw-retained conventional crowns and bridges, or hybrid metal and acrylic screw-retained bridges) or removable, precision attachment-retained partial or complete dentures.

5.2 Planning dental implants

It is essential, as with any episode of treatment planning, that the final outcome is taken into account at the outset of the planning process. That is not to say that a treatment plan, once formulated, is inflexible, but an opportunity or contingency plan to manage any potential problems before they occur is likely to be of considerable benefit. Consideration of the final restoration and the expectations of the patient must, therefore, be made at the outset so that the treatment plan can achieve the most desirable outcome.

Indications

Osseointegrated implants provide the retention and support for the dental prosthesis that may take the form of a single tooth, groups of teeth, the entire dentition or even anchorage for an orthodontic appliance. Implants are primarily indicated, therefore, when there is partial or total loss of the dentition and/or the supporting tissues. The loss of tissues may be a consequence of extensive dental caries and periodontitis or due to more radical change such as neoplasia or maxillofacial trauma.

Contraindications

Implant surgery may be considered as an elective oral surgical procedure and therefore any contraindications for surgery will also be a contraindication for the provision of dental implants. In general terms, any local or systemic condition which would impact upon wound healing will have the same effect upon the healing at the implant site and may, therefore, impact on the long-term success of implant management, for example the use of bisphosphonates to manage osteoporosis and the link with postsurgical osteonecrosis.

Relative contraindications for treatment may be considered in relationship to the space available for implant placement and restoration. Cases may present with insufficient bone quantity (e.g. a highly atrophic anterior mandible or a posterior maxilla with a highly pneumatised maxillary sinus). There may also be insufficient space to place the restoration (e.g. a severely overerupted tooth opposing the site planned for restoration).

Case selection

The selection of cases for implant treatment will begin with careful and thorough history and examination. It is important to determine why the patient is seeking implant treatment and to ascertain their understanding of what is involved, as well as finding out their expectations of the likely clinical outcome. It should then be possible to balance the patient’s expectations with what is clinically achievable to ensure that both the patient and the clinical team are likely to be satisfied with the outcome. During history taking, it is crucial to discuss problems (e.g. a pronounced gag reflex with a removable prosthesis) that may have been encountered with previous restorations and also to determine whether implants are indeed the appropriate line of management. For a patient with a severe gag reflex, it may be more appropriate to undertake desensitising measures first rather than placing multiple implants that may not be used for the support and retention of a prosthesis.

Careful discussion of the care pathway should be undertaken with the patient to ensure that (s)he understands what the different stages of treatment will involve. For example, during the healing phase, it is sometimes necessary to ask the patient not to wear an interim prosthesis for a short period in an attempt to aid healing. This may not be acceptable to some patients. The actual methods for placement and restoration of the implants and their long-term management should also be considered carefully.

Finally, the cost of delivering this type of treatment must be considered, irrespective of whether it is self or publicly funded delivery of care. The initial outlay is considerably more when comparing complete dentures to implant supported overdentures. There is evidence, however, to suggest that the long-term costs of these different methods of management is not so great, and this does not take into consideration the psychosocial aspects of comparing these two treatments.

Tooth down planning

The final restoration of the implants should be considered at the outset of treatment planning. The question of whether it is possible to place teeth in their ideal position to restore function should also be considered. A decision should be made as to whether it is important or desirable to conform to the features of the patient’s remaining dentition or current prosthesis or whether any modifications to the current situation need to be made. Accurate preoperative study casts, mounted on a semiadjustable articulator, will support the planning process and enable simulation of the final restoration by using a diagnostic wax-up or try-in prosthesis.

There are biometric and subjective measures that may be used to assess dental function. Valuable information may also be gathered during history taking when the patient’s ability to chew and potential difficulties with speech and aesthetics may be explored. Particular consideration to facial, dental and gingival aesthetics should be made when restoring the anterior aesthetic zone. For example, it is unacceptable to restore a implant which may be stable but demonstrates poorly adapted supporting tissues in cases where there is a high upper lip line.

Special investigations

An estimation of the quantity and position of hard tissues may be measured clinically with callipers that penetrate the overlying soft tissues to estimate bone width along an edentulous space. A detailed clinical examination needs to be supplemented with additional assessments such as plain film radiography, tomography or computed tomography (CT) scanning. There are also software applications that use radiographic data to generate 3D simulations which can be viewed and manipulated to allow further treatment planning. Products exist to allow clinicians to design restorations and determine optimum implant placement before requesting custom surgical guides and prefabricated restorations prior to implant surgery.

Types of restoration

Restorations supported by dental implants may be classified into two broad groups: first, those that replace only the lost dental tissues and are therefore directly comparable to conventional single crowns or bridges with the dental implants effectively being the ‘roots’ of the teeth; and second, the r/>

Stay updated, free dental videos. Join our Telegram channel

VIDEdental - Online dental courses